Celebrating Ninon Sevilla 1929-2015

Today, Mediático presents a tribute to Ninón Sevilla, the Cuban-born actor who died on January 1 2015 at the age of 85. The tribute has been written by one of Mediático‘s founding co-editors, Dolores Tierney, Senior Lecturer in Film Studies at the University of Sussex and author of Emilio Fernández: Pictures in the Margins (Manchester University Press, 2007). Last year, Tierney published a co-edited anthology (with Deborah Shaw and Ann Davies) The Transnational Fantasies of Guillermo del Toro (Palgrave Macmillan, 2014) which includes her chapter on “Transnational Political Horror in Cronos, El espinazo del diablo, and El laberinto del fauno“. She also recently co-edited Cinema Journal’s In Focus feature (with Ana López) on “Latin American Film Research in the Twenty-First Century”, which included her essay “Mapping Cult Cinema in Latin American Film Cultures,” and she also produced an InMediaRes post “Reflections on Film Scholarship and the Internet”. She is currently completing a book about transnationalism and film directors across Latin American cinema (for Edinburgh University Press).

Celebrating Ninón Sevilla 1929-2015

By Dolores Tierney

It was with some sadness that I learned, earlier this month, about the death of Ninón Sevilla, Cuban-born star of classical Mexican cinema and latterly character actress of Mexican telenovelas. When I first encountered her in film, largely via the work of John King and Ana López, I found her thrilling and amazing. Already a fan of the dancing in the American film musical, I found Sevilla’s gyrations in Mexican films a revelation.

Sevilla was one of several Cuban rumberas (dancers) who flourished in the classical Mexican cinema of the late 1940s and early 1950s. Sevilla, Maria Antonieta Pons and Rosa Carmina became famous in the singularly Mexican genre of the cabaretera –a brothel melodrama/musical hybrid featuring lavish musical numbers, gritty drama and copious amounts of suffering. The protagonists of these films were often virtuous young women reduced to a life of sin by forces “beyond their control.” They were either dancers (ficheras) paid tokens (fichas) to dance (but also sleep) with their clients or nightclub dancers (rumberas) who were also, (the narratives made clear) expected to sleep with clients. Whilst the protagonists of the fiercely patriarchal cabareteras were often defined through the sacrifice of their bodies as sexual objects for men and for their families, Sevilla (and the other Cuban rumberas), could also portray overt sexuality enjoying the dance, their bodies and shockingly their own desire.[1. In one scene in the year 1949 remake of La mujer del puerto (Emilio Gómez Muriel) Maria Antonieta Pons does a sultry solo dance to a jazz number for Tito Junco, who spoiler alert turns out to be her brother. The clip I’m referring to starts at 3m55s.]

Although the characters Sevilla played were mostly Mexican, it was enough that as a blonde, exotic beauty, she looked, spoke and moved like she was from somewhere else, for these displays to be permissible within the boundaries of conservative classical Mexican cinema.

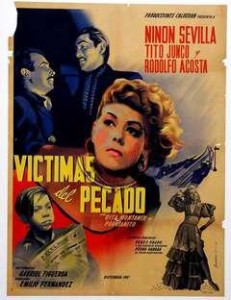

And it was Sevilla’s overt, sexuality that make her so exciting and the dances she choreographed and appeared in (most of which were predominantly Afro-Cuban in style) so jaw-droppingly amazing. Take for instance a scene in Emilio Fernández’ Víctimas del pecado (1949) where Sevilla’s character Violeta performs an impromptu rumba (this comes at about 1h 8 mins into the film).

The spontaneity of her performance is emphasised by the fact that she is not wearing the rumbera outfit (which would usually expose thighs, stomach and breasts), but a more demure evening dress (which has the effect of making her less of an object of male voyeurism). Violeta dances freestyle initially in front of the band, half facing toward them, taking her cue from their rhythms. She then drags one of the black musicians up to dance with her. Although they dance together, they do not hold each other, but mirror each other’s steps in a kind of duel format – she does a step and then he answers with a different step. The smiles on their faces suggest that they are taking mutual pleasure from each other’s dance. At one point she lies on her back and at another she wiggles her behind in his face. It is an immensely erotic sequence and highly unusual in classical Mexican cinema because of its interracial nature – a white woman dancing with a black man. As with many of Sevilla’s numbers this dance sequence works against the containing patriarchy and racial ideology of Mexican cultural nationalism.[2. Tierney, Emilio Fernandez (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2007), 139.]

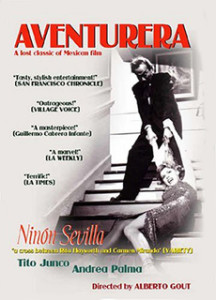

The French critics loved Sevilla. Raymond Borde said of her “Ninon Sevilla est la seule danseuse qui aille aussi loin dans la simulation de l’acte sexuel. Son attitude favorite : renversée sur le dos, les jambes pliées et palpitantes”.[3. Positif n° 10, 1954 “Ninon Sevilla is the only dancer to go this far in the simulation of sex. Her favourite position is to lie on her back, her legs bent and trembling” (!).] When Víctimas del pecado premiered in France in 1952 it was a huge success, and many French critics preferred it to the film that made her a star Aventurera (Alberto Gout, 1949).

My love of Sevilla in the classical cabareteras stemmed not just from the fact that could sexually circumvent many of its ideological norms. I also loved her because, although patriarchy victimised her, she was almost never a victim. She conveyed herself as an active, thinking woman, with a keen sense of the ideologies that repressed her and other women. Her proto-feminist self awareness is suggested in a musical sequence from Aventurera where music acts subjectively to give an insight into what she is thinking.

Popular Mexican singer Pedro Vargas sings the title song ‘Adventuress’ written by Agustín Lara (who wrote many of the boleros that feature in the cabareteras) while Elena (Sevilla), a rumbera/prostitute wanders around in front of the stage. Rather than focusing on the singer, the very popular Vargas, the camera follows Elena around the room and eye-line matches suggest he is really singing to her. The lyrics implore: ‘Vende caro tu amor Aventurera/ Da el precio del dolor a tu pasado/Y aquél que de tus labios la miel quiera/que pague con brilliantes tu pecado’ (Sell your love expensively Adventuress/Give a price to the pain of your past/And he who wants honey from your lips/Let him pay for your sins with diamonds). Sevilla’s proto-feminist moment is often considered an anomaly in the otherwise patriarchally organized cabaretera genre -as is the end of the film where she ends up, not punished but living “happily ever after” (albeit with her husband and hence within patriarchy). But if we look at Sevilla’s characters in these films many were, like Elena, agents of their own destiny.

In Sensualidad (1951) for instance, another Alberto Gout cabaretera (and also another hybrid, this time crossed with the film noir), Sevilla plays a prostitute who takes revenge on the judge who sent her to prison, by seducing him and causing him to abandon his wife, his family and his senses.

Víctimas del pecado: Sevilla uses her feminine wiles to seduces the judge (Fernando Soler) who imprisoned her

Sevilla’s agency was communicated in her body language even when she wasn’t dancing. In the “Aventurera” sequence for instance, her sashaying walk, cigarette smoking and shiny dress give a sense of independent movement outside the rigid structures of the couple-dancing that as a fichera she was compelled her to do.[4. Tierney, “Silver Sling Backs and Mexican Melodrama: Salon Mexico and Danzón,” Screen vol. 38, no. 4, 360-371, which gives an account of how the couple dances in cabaretera act as tools of patriarchal repression to structure female movement.] In the “Aventurera” sequence , her costume and performance style also channels, another (bad girl) Latina sex symbol of the era, Rita Hayworth (Margarita Cansino) as she was in Gilda (Charles Vidor, 1946).

Ana López talks about the “Aventurera” sequence as an “excess of signification”– where Sevilla’s “haughty cigarette-swinging walk” goes beyond the boundaries of the melodrama’s patriarchal norms which situate her character, at the end of the film safely within marriage and out of the cabaret.”[5. Ana López, “Tears and Desire: Women and Desire in the ‘Old’ Mexican Cinema,” The Latin American Cultural Studies Reader, eds Ana del Sarto, Alicia Rios and Abril Trigo, 453.]

Sevilla starred in a string of cabareteras directed by Gout (including No niego mi pasado, 1951 Mujeres sacrificadas, , 1951 Aventura en Rio, 1952) and other directors (Señora Tentación, José Diaz Morales, 1947, Coqueta, Fernando A. Rivero, 1948, Perdida Fernando A. Rivero, 1949, and Llévame en tus brazos, Julio Bracho, 1953). She also returned to Cuba to star in two Mexico/Cuba co-productions, Mulata, Gilberto Martínez Solares, 1953 and Yambao (Alfredo B. Crevenna, 1957), in which she appeared in blackface. Later in the 1950, as the Mexican industry’s popularity wained, like other Mexican stars she made films abroad, in Brasil La mujer de fuego, (Tito Davison, 1958) and Spain Música de ayer, (Juan de Orduña, 1959)

Sevilla returned to the cinema for Noches de Carnaval (1981) for which she won the Ariel (Mexican Oscar) and then appeared in a string of telenovelas throughout the 1980s, 1990s and 2000s. I remember her most from Televisa’s Rosalinda (1999) where, as a comadre from the vecindad she was usually there to loudly lament the latest tragedy to befall the heroine .

In recent cinema, Sevilla and her films have featured in Viviana Garcia Besné’s excellent documentary account of her filmmaking family the Calderóns, Perdida (2009) which takes its title from one of Sevilla’s cabareteras. The Calderón studio produced many of Sevilla’s films and launched her to stardom.

¡Adiós Ninón!

Notes