Markus Nornes (University of Michigan)

The first and last thing to say about the Taiwan International Documentary Film Festival is that the audiences were truly impressive. Allow me to explain in a somewhat roundabout way with a story.

I attended the Taiwan International Documentary Film Festival having had the honor of co-organizing a retrospective of films by the Japanese master Ogawa Shinsuke. The occasion to revisit these films brought me back to my first encounter with the director. The setting was the 1989 Hawai’i International Film Festival, which was showing Ogawa’s Sundial Carved With a Thousand Years of Notches (Magino monogatari: sennen kizami no hidokei, 1987). This was Ogawa’s last major film before his untimely death in 1992. It is also one of his finest, most compelling efforts, despite the 4 1/2 hour running time.

I was Ogawa’s attendant during his stay in Honolulu. The evening of his first screening, I accompanied him to the after-film discussion. Word had come down that the theater was filled with a couple hundred spectators. We arrived 10 minutes before the credits, so I snuck into the auditorium to check out the crowd. It had dwindled to just a handful of stalwart viewers! Dreadfully embarrassed, I went out to the lobby and sheepishly rejoined Ogawa. I told informed him that only a handful of people were left in the seats. His response was cheery and totally unexpected: “Oh, it’s OK. It’s OK. It’s always like that, and that’s just fine. You know, the people who stayed are the people I want to talk to, and we will have a great discussion!” Indeed, we did.

Over a quarter-century later, I attended a screening of the film in Taipei and I could not help recalling this episode. This time, I was conducting the after-film discussion, and without Ogawa. Once again, word came down that a couple hundred people had bought tickets for the film. I expected to greet a handful of them at the end of the film; after all, I’ve shown Sundial in various contexts over the years and walkouts are to be expected for this demanding work. Indeed, the notes for my opening comments started with the Hawai’i story.

However, much to my surprise, when the lights went up the assembled audience filled most of the auditorium. Although I’m sure their bodies were crying for relief, nearly all of them stayed in their seats for the discussion. It was quite amazing—even unprecedented. Yet, I have to say that every screening at the festival was like this, no matter the film. I have never been to a documentary festival with the level of passion I felt in the theaters of the Taiwan International Documentary Film Festival.

This fervent audience had a rich slate of films to choose from. Naturally, there were the competitions. The international competition offered up a solid, if unsurprising selection of world documentary. However, I was impressed by the attention the festival paid to Asian documentary. They devote a competition to it in the Asian Vision competition; but they also have a program of new Taiwanese documentary. And the non-competitive Panorama section serves as a grab-bag for strong festival films, many of which are from neighboring countries.

All this is great, and all that one expects from an international film festival. At the same time, the heart and soul of a festival can be discovered in its original programming. This is where the organizers make their mark and bare their souls. And the programming in the back half of the catalog is incredibly creative and important.

Three retrospective programs—for independent Taiwanese documentary, restorations of amateur movies from the colonial era, and newsreels the dictatorship produced with the US between 1951 and 1965—evidence a love of history. Here the organizers of TIDFF are playing an important role in discovering, celebrating and canonizing their own roots. This also came out in the special award granted to the early video activism collective Green Team. Taiwanese film was easy to find in every nook and cranny of the festival, but it also filled a competitive section of 15 films culled from nearly 200 entries.

At the same time, the brilliant Documemory: Inter-view program was more analytical, even theoretical; it took the device most filmmakers use to gather evidence and claim an objective grasp of history and undercut it. The films collected here questioned the personal stakes behind testimonies or even called into question reality itself. Similarly, the short film program entitled Stranger Than Documentary packaged films clearly designed to open up the audience’s definitions of what constitutes documentary. The master class by Alan Berliner surely accomplished the same thing; I can’t think of a better choice from world documentary today.

Finally, a social conscience came out in two important retrospectives. A slate of the influential films of Ogawa Shinsuke could not have been better-timed, considering the Sunflower movement broke out in the midst of planning. Ogawa’s films are like a primer for movement documentary, and also hold crucial lessons for social committed filmmakers for after the political season is over. The program was entitled 11 Flowers of Movement Cinema (小川紳介回顧:運動電影的11朵花) to connect it to the recent political events, which were very much on everyone’s minds.

The forum I organized was unique in the history of Ogawa-related events. First, it was the first time that one of the female members of the collective sat on a panel to talk about her experience. Hatanaka Hiroko joined the collective during the late Magino phase, and basically ran the house. She spoke eloquently about the personal and political challenges of collective living. The two other speakers helped connect the Ogawa retrospective to Chinese cinema. Akiyama Tamako, a scholar of Chinese documentary from Rikkyo University, has served as the primary interpreter (and a subtitler) for the Yamagata International Documentary Film Festival since 1993. Very much “on the scene” for the entire development of Chinese and Taiwanese documentary, she described first encounters with Ogawa and the Japanese director’s subsequent influence through video, film festival retrospectives and translation. The last panelist was director Wu Yii-fen. The forum featured a number of clips from a visit Wu paid on Ogawa. This was just months before the director’s death, and would be Ogawa’s final interview. Wu talked about this encounter and the impact it had—along with the films—on his own practice. Indeed, of all the independent Chinese documentary filmmakers influenced by Ogawa Shinsuke, Wu and the filmmakers of Full Shot are probably the ones who came closest to adopting Ogawa’s core principles.

I was also impressed by Salute! Independent Documentaries in China. Even the name is wonderful. It was, indeed, a salute to the accomplishments of colleagues on the mainland, as well as a touching show of support for their current problems with government suppression. The films constituted a broad overview of mainland practice over the past decade. The mainstay of direct cinema was strongly represented by a number of films, such as Timber Gang (Yu Guangyi, 2006) and The Last Moose of Aoluguya (Gu Tao, 2013). At the same time, there were two representative samples from the CCD Workstation Memory Project from Zou Xueping, the testimony-based Spark (Hu Jie, 2013) and quirky films like Tape (Li Ning, 2010), Ximaojia Universe (Mao Chenyu, 2009) and Yumen (Huang Xiang, J.P. Sniadecki, Xu Ruotao, 2014).

Aside from this solid sample of mainland approaches, I was impressed that the festival lined up Zhao Liang’s celebrated Petition (2009) with Born in Beijing (Ma Li, 2011). The films deal with the same petitioning system, were both the result of long-term study and close relationships with their subjects, and equally powerful films (if there is a difference, it is the often lovely cinematography of Ma’s film. That both films are long, 315 and 233 minutes respectively, evidences a film festival that puts substance above ticket sales. Of course, it once again speaks to the fervor of Taiwanese audiences for the documentary.

Salute! Independent Documentaries in China could be seen as something of a tip of the hat to TIDF’s mainland counterparts: the Beijing Independent Film Festival, China Independent Film Festival, Chongqing Independent Film and Video Festival, and the Yunnan Multicultural Visual Festival. There was a forum populated by programmers from these festivals. MC Kuo Li-hsin sat with Wang Hongwei (BIFF), Zhang Xianming (CIFF), Chen Dongmei (CIFVF), along with two of the mainland’s most challenging directors, Hu Jie and Ying Lian (Yumfest’s Yi Secheng was slated for an appearance, but could not attend). The panel described the present situation, which is particularly difficult for programmers. At one point, I asked why the government didn’t just shut the whole thing down, since they clearly have the power to do so. Wang Hongwei suspected that the government needed the festivals to develop its policies on culture, and was content to let them run to the extent that they avoided sensitive films. Ying pitched in with the observation that the government seemed to understand the reality of the festivals in the late 2000s when Ai Weiwei took up the camera; this, along with the 2012 leadership transition. But the most satisfying speculation came from Chang and Zhang, who suggested that the government officials simply have no idea what they want. Chang slyly compared policy to “contemporary art”—protean, vague in intentions, and always moving forward.

In short, the TIDFF renovation has resulted in an exciting festival that celebrates the radical heterogeneity of the documentary form. All these impulses are contained in the seven exhilarating minutes of my favorite film of the festival: Yuan Goang-ming’s The 561st Hour of Occupation. This deceptively simple film features a camera gliding over the Legislative Yuan during its occupation by the Sunflower Movement activists. It provokes the audience to think analytically, aesthetically, politically, historically, and theoretically—like the sum of this festival itself.

Markus Nornes giving a Q&A to an energetic audience that assembled for an morning screening of an Ogawa Productions film.

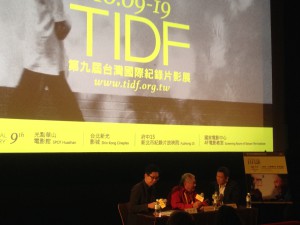

Panelists for the Ogawa Productions Forum (left to right): Wu Yii-feng, Markus Nornes, Hatanaka (Iizuka) Hiroko, Akiyama Tamako.

Typical late night communion at an outdoor market, with (left to right) Joanna Wang (secretary of Taipei Documentary Filmmakers’ Union), Matsubayashi Yoju (director), Mickey Chen (director, author), Fujioka Asako (producer, programmer, Yamagata Documentary Film Festival board member), Dai Chong-yuan (producer and taxi driver), Wu Yii-feng (director), Wood Lin (TIDFF director), Kite Chen (activist), Markus Nornes (film scholar), and Wu Yao-tung (director).

An Outstanding Contribution Award was presented to the 1980s guerilla video collective Green Team. It has recently donated 3,000 hours of footage to Tainan National University of the Arts for preservation and digitization. From right to left: Lin Shin-I, Wang Chi-chang, Lee San-chung, Fu Dau, and Hsien Weng-sheng.

Moderator Kuo Li-hsin (far left) lead a discussion with (left to right) Wang Hongwei (BIFF), Zhang Xianming (CIFF), Chen Dongmei (CIFVF), along with two of the mainland’s most challenging directors, Hu Jie and Ying Lian.

Pingback: Report on the 2014 Taiwan International Documentary Film Festival | Chinese Film Festival Studies Research Network