BY RICHARD GRUSIN

In June 2002, for a plenary lecture in Montreal at the biennial Domitor conference on early cinema, I took the occasion of the much-hyped digital screening of Star Wars: Episode II–Attack of the Clones (George Lucas, 2002) to argue that in entering the 21st century we found ourselves in the “late age of early cinema,” the more than century-long historical coupling of cinema with the sociotechnical apparatus of publicly projected celluloid film (“Remediation”). Two years later, in a lecture at a conference in Exeter on Multimedia Histories, I developed this argument in terms of what I called a “cinema of interactions,” arguing that cinema in the age of digital remediation could no longer be identified with its theatrical projection but must be understood in terms of its distribution across a network of other digitally-mediated formats like DVDs, websites, games, and so forth—an early call for something like what now goes under the name of “platform studies” (“DVDs”). In his recent book on “post-cinematic affect” Steven Shaviro has picked up on this argument in elaborating his own extremely powerful reading of the emergence of a post-cinematic aesthetic (70). I want to return the favor here to take up what I would characterize as a kind of “post-cinematic atavism” that has been emerging in the early 21st century as a counterpart to the aesthetic of post-cinematic affectivity that Shaviro so persuasively details.

Sometimes considered under the name of “slow cinema” or “the new silent cinema” (or, as Selmin Kara puts it, “primordigital cinema”), post-cinematic atavism is not limited to art-house or independent films. Indeed three of the nominees for Best Picture at the 2012 Academy Awards—Hugo (Martin Scorsese, 2011), The Tree of Life (Terrence Malick, 2011), and the winning film The Artist (Michel Hazanavicius, 2011)—participated in this renewed attention to earlier cinematic moments and aesthetics. Each of these films, as well as Lars von Trier’s 2011 Melancholia, which I will address in detail in this essay, makes stylistic, aesthetic, and cinematic choices that exhibit or display a kind of atavism—a reversion to or reemergence of an earlier cinematic moment through the anachronistic expression in the present of prior, even outmoded cinematic traits that otherwise appear to have become extinct in the proliferation of hypermediated, digital, post-cinematic technical and aesthetic formats.[1] As such these films mark an increasing recognition in Hollywood of a fundamental shift: the ultimate extinction or disappearance of the platform of celluloid film and a consequent fear of the potential decentering of the film industry from the US across the globe as new digital film technologies allow for the inexpensive production and distribution of feature films, exemplified perhaps most dramatically in the success of Nigeria’s Nollywood.

It is not accidental, therefore, that both The Artist and Hugo take as their subjects the passing of earlier aesthetic-technical formations in the history of cinema. Indeed both films remediate outmoded cinematic forms through the use of contemporary digital cinematic media technologies, seeking both to preserve and to mark the disappearance of these earlier cinematic apparatuses. Despite sharing the project of remediation, which Jay Bolter and I defined in our book of the same name, these two films express their post-cinematic atavism in distinctly different ways. In The Artist, for example, Michel Hazanavicius chooses to present a story of the film industry’s transition from silent film to sound in the medium of silent film—an unconventional atavistic choice that was not necessary to tell this story but which aimed to produce a cinematic experience akin to that of film audiences of the first third of the 20th century. Hazanavicius could just as easily have chosen to present the film’s silent cinematic sequences without sound while using sound in presenting the off-screen scenes. Indeed in a 21st-century film this would have been a more realistic or accurate (although less atavistic) presentation of the world of silent cinema in which films were silent but private and public embodied space was not. But doing so would not have called attention to The Artist’s self-conscious remediation of silent cinema. (See Figure 1, below).

Shot in 35mm but edited and most often projected digitally, The Artist seeks to capture the look and feel of silent cinema to remind us of its strategy of remediation (see Fig. 1). Not only did Hazanavicius shoot the film in 35mm rather than digital, but he used the classic Academy Ratio of 1.37:1 rather than the widescreen format more commonly used in contemporary cinema. The film’s aim to faithfully remediate the silent era is thus signaled from the beginning. The opening credits sequence begins in the style of early silent cinema; the soundtrack only begins as the silent-era credits give way to contemporary credits. But it is only during The Artist’s opening sequence that we learn that there will be no spoken dialogue in the film. Hazanavicius’s first shot, which shows a (fictional) 1927 silent “George Valentine film,” Long Live Free Georgia, being screened in a theater, unifies our screen and the screen in the fictional theater, filling the screen of the 2011 projection. After this initial sequence the film cuts to a shot of the audience in the theater and the orchestra playing the music we’re hearing. This is an interesting opening which makes this music simultaneously diegetic and non-diegetic—diegetic to The Artist but extra-diegetic to Long Live Free Georgia, underscoring the fact that diegetic sound only came into existence after the introduction of talkies. It is only after we see the end of Long Live Free Georgia that we realize for certain that The Artist will be silent; as the music for Long Live Free Georgia ends, we see intertitles and hear non-diegetic music for The Artist, itself a silent film but sans orchestra.

The film’s narrative problematic—the replacement of the silent cinema regime as a result of the new technological developments that lead to the talkies—stages the process of remediation as reform that the film itself would challenge, or at least resist. When George Valentine (Jean Dujardin) is on the decline as a silent film star and Peppy Miller (Bérénice Bejo) is a rising talkie star, Hazanavicius has Peppy rehearse the avant-garde logic of new media and remediation as reform rather than the atavistic logic of the film, as she tells an interviewer: “Out with the old. In with the new. Make way for the young.” While The Artist’s atavistic remediation of silent cinema would, at least for the duration of the film, temporarily bring back the cinematic aesthetic of silent film, its narrative resolution suggests another way in which the silent aesthetic persists in contemporary cinema, as the persistence of what Tom Gunning has called the “aesthetic of astonishment” at work in the “cinema of attractions” (“Astonishment”). What ultimately solves the problem of the end of George’s career (as a metonymy for the end of the silent era) is Peppy’s idea for George to perform with her in a song and dance number, which Gunning has argued is one of several ways in which the early cinema of attractions has gone “underground” and remains as a crucial element of film, even in our post-cinematic digital era (“Attraction” 64). Indeed, after the successful dance scene with Peppy and George, The Artist finally finds its voice, comes into sound. The film achieves this through an atavistic embrace of the spectacle, the attraction, the aesthetic of astonishment, all of which eschew the naturalistic, realistic narrative style that the introduction of sound and continuity editing is said to provide. In this sense, then, The Artist remains an atavistic remediation to the end.

Like The Artist, Martin Scorsese’s film Hugo remediates an earlier moment of cinema, Georges Méliès’s cinema of illusions, in the spirit of post-cinematic atavism. Unlike Hazanavicius, who expressed his film’s atavism by remediating the style of silent cinema and shooting on 35mm, Scorsese makes explicit nods to Méliès’s illusionary style through the deployment of the most recent media technologies in directing Hugo, his first 3D film and his first film shot in digital. Scorsese’s choice to abandon celluloid film for a movie celebrating the earliest moments of cinema (and detailing the near loss of that historical Méliès moment) makes Hugo speak precisely to the question of our current post-cinematic moment and the possible loss of other elements of cinematic history in the face of the new post-cinematic affective style. Hugo makes the case (in digital 3D) for the continued relevance of the earliest moments of cinema’s history at precisely the time that the late age of early cinema is coming to an end. More specifically, Hugo, like The Artist, makes a cinematic claim for the non-indexical, non-realist origins of cinema. Contra, among others, André Bazin or Stanley Cavell, Scorsese sees the hypermediacy of magic and illusion, rather than the transparent immediacy of photographic indexicality, as constituting the true character of film (Bolter and Grusin). Scorsese (see Figure 2) lovingly presents us with a variety of early 20th-century media of representation, communication, and transportation, from the opening shot of the mechanism of the train station’s clock to the multimediated notebook that is at the heart of the film’s narrative crisis to the railroad itself.

The argument for cinematic illusionism is underscored by the brilliant casting in the film (as Inspector Gustave Dasté) of Sacha Baron Cohen, whose own cinematic and televisual career is based not on the indexical reporting or reproduction of the real but rather on using non-indexical techniques and the cinema’s claims to indexicality for the purposes of illusion or deceit.

While both Hugo and The Artist deploy the techniques of hypermediacy and remediation to manifest the post-cinematic atavism of the first decades of 21st-century cinema, both films remain indebted to an affectivity and an aesthetic rooted in the late age of early celluloid film. The same is not the case for Lars von Trier’s extraordinarily moving film Melancholia, whose atavism is not explicitly concerned with the end of the early cinematic era of celluloid film, but rather with the end of the world. Where Hugo and The Artist both made their remediation explicit, calling attention to their hypermediacy, Melancholia is more immersive, not in the sense of late 20th-century cyberspace or virtual reality but in an affective sense similar to what Shaviro details as post-cinematic affect. The film’s title, which names the planet that is on a collision course with the Earth, has been widely taken to refer as well to the emotional state of Kirsten Dunst’s character Justine. In his very fine 2012 essay, “Melancholia or, The Romantic Anti-Sublime,” Shaviro invokes (but does not entirely embrace) the idea that the impending collision of Melancholia with Earth (presented both in the film’s opening and in the second half of the film) is an “inflated ‘objective correlative’” of Justine’s “psychological state.” What I want to suggest, instead, is that if there is an objective correlative in Melancholia it is the apparatus of cinema itself, and that the film’s atavistic tendencies (to borrow the title of Dana Seitler’s excellent book on atavism and modernity) also concern the disappearance of the historical era of celluloid film, a loss addressed in the late 20th century by the formation of the Dogme 95 group of which von Trier was a founding member. Insofar as the psychological condition of melancholia is usually historically oriented, connected with or brought on by some prior loss, it makes sense to take the film’s title to refer more broadly to von Trier’s melancholia for the loss of cinema, the end of the late age of what Gunning described as the “cinema of attractions” and its historical emergence within a photographic, celluloid-based apparatus—including its creation, production, distribution, and exhibition. Thus von Trier’s melancholia is not only for the world that is ending in the film but also for the end of a certain techno-historical material formation, emerging in early cinema and its aesthetic of astonishment, though persisting as an ongoing potentiality in cinema of any era, arguably even a post-cinematic one like our own.

Although von Trier contends in an interview that Melancholia is “perilously close to the aesthetic of American mainstream films” (qtd. in Leigh), this does not seem apparent to a casual moviegoer in any obvious way. The film’s post-cinematic atavism is marked by a slow-motion style and hyper-melodramatic non-diegetic music that runs counter to the current mainstream cinematic style of quick cuts and sampled music. Melancholia’s cinematic atavism begins, I would contend, from its opening remediation of the cinematic “overture,” a feature that has its origins in the early sound era and which reached its peak in the 1960s. The almost hallucinatory, dream-like musical sequence at the film’s opening concludes with an affective premediation of the film’s end, an image of the two planets coming together, vaguely reminiscent of the famous shot of the rocket crashing into the moon in Méliès’s Le Voyage dans la lune/A Trip to the Moon (1902) (see Figures 3 and 4).

Although clearly set in the present or very near future, the film’s stylistic atavism is evident in the mise-en-scène of the wedding reception which takes up the film’s first half, with the white bridal gown (atavistic in itself), as well as the dress clothes and upper-class furnishings, and the ritualistic formality of the speeches and toasts. Not incidentally, the only digital medium present in the film’s first half is a video screen displaying an advertising photograph for which Justine is expected to provide a tag line. Remarkably, despite the film’s contemporary setting, not a single guest is texting, talking, or checking email on their mobile phones. Justine’s own atavistic tendencies are evident as well in the widely remarked scene where she takes down the art books displaying constructivist images by Kazimir Malevich and replaces them with more representational images by Brueghel, Caravaggio, and Millais.

The film’s most dramatic and explicit atavistic references to early cinema, however, come at the end where the collision of the two planets premediated in the overture alludes to two mythic episodes from the history of early silent cinema in which the diegetic action on the screen is aimed at the audience. The first, often seen as the inaugural moment of theatrical motion picture projection, involves an early film by the Lumière brothers, L’arrivée d’un train en gare de La Ciotat (1896), which was reported to have sent audiences screaming from the theater in fear that the train would run into them. The second instance, alluded to by the ultimate collision of Melancholia with Earth that ends the film, with Melancholia coming ever closer to both the film’s audience and its main characters, is the famous final shot of The Great Train Robbery (Edwin S. Porter, 1903) where the outlaw points his gun right at the audience (see Figures 5 and 6). Although neither of these moments visually resembles the final images of Melancholia, they do resemble one another affectively in their threateningly direct cinematic address to the audience.

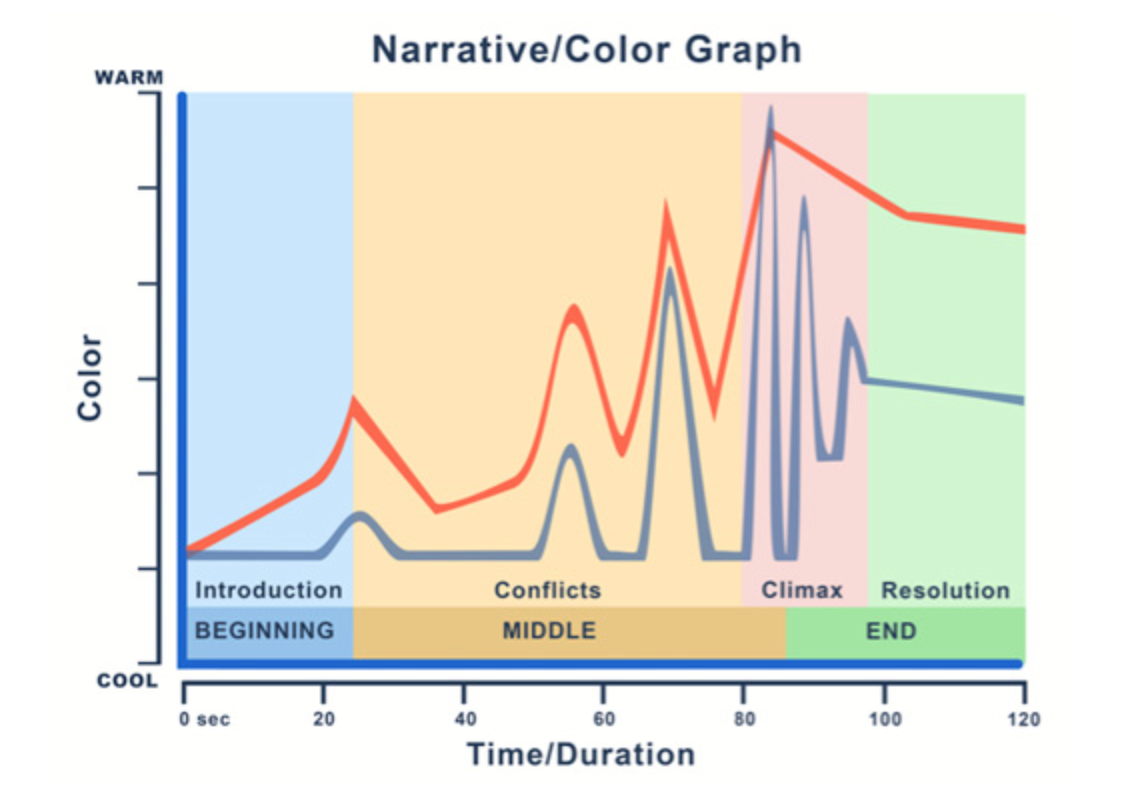

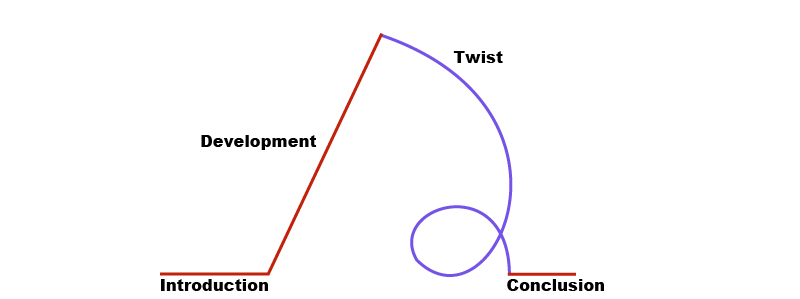

Despite the end of the world depicted at the end of the film, however, Melancholia is not conventionally apocalyptic. Or rather it is apocalyptic precisely to the degree that the apocalyptic ending of its cinematic narrative is not unique or extraordinary but rather exemplary of the kinds of narrato-technical endings to which all films are subject, the quotidian apocalypse at the end of the production and screening of every film. More specifically there is in all films a temporal movement or arc from the first frame to the last, whether in the technical event of screening and projection of a material artifact that has a certain limited duration, or in the cinematic narrative which also has a corresponding temporal limit as often set out, for example, in pedagogical diagrams about cinematic narrative (see Figures 7 and 8).

It is customary of course for these two temporal trajectories to end at the same time (or more exactly at almost the same time, as the customary screening of credits after the film’s narration ends belies the identity of these two apocalyptic temporalities). This coincidence of narrative and cinematic termination in Melancholia seems far more dramatic and powerful than in most Hollywood films, however, insofar as the collision of narrative and technical durations coincides with the collision of the two planets and the eradication not only of the diegetic world on the screen but of the cinematic image itself—as von Trier makes the screen go black for several seconds before the credits begin.

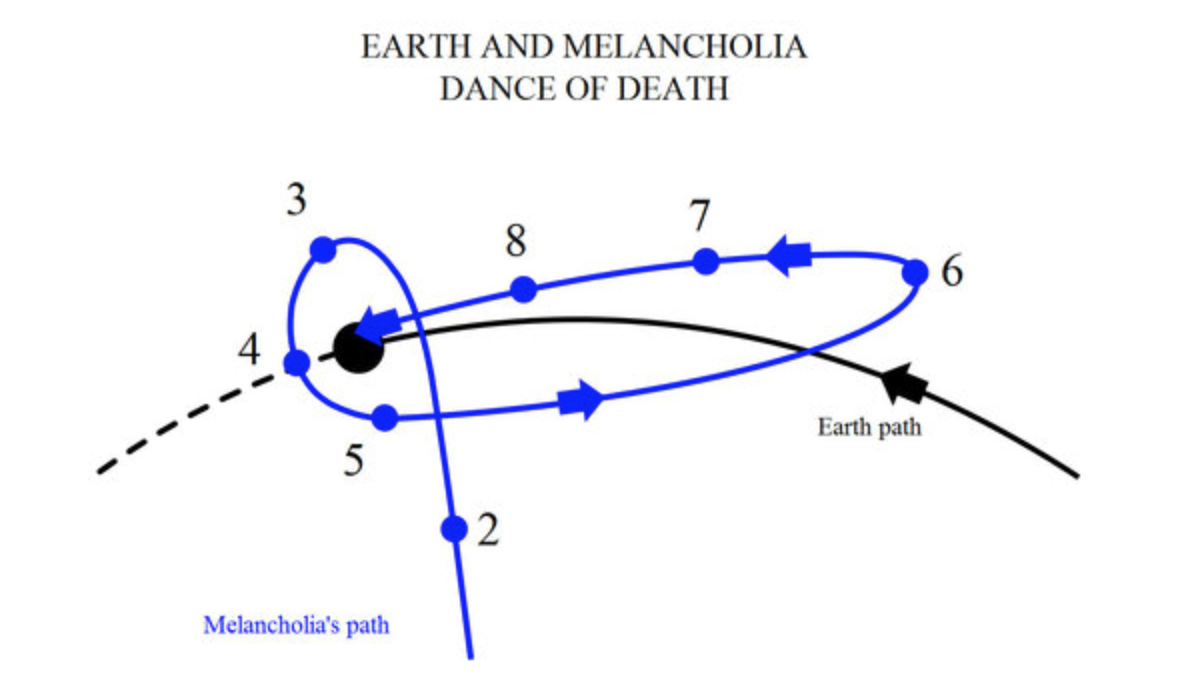

Not only is this collision premediated more quietly in the film’s overture but it is schematized more explicitly in Part II of the film in the diagram that Claire sees online and fails to print when the power is shut off by the impending approach of the planet Melancholia. This image of the earth’s orbit intersecting the erratic movement of Melancholia is another atavistic moment, deploying a kind of graphic diagram that one can readily find in a pre-digital age, entitled (also atavistically) the “Dance of Death” between Earth and Melancholia (see Figure 9).

Pairing these two kinds of collision we can see that the Earth’s regular orbit functions like the regular mechanical operation of the cinematic apparatus, with its linear arc, while the irregular orbit of the planet Melancholia stands in for the operation of the cinematic narrative of the film Melancholia. Understood in this way we can now recognize that when the planet crashes into earth at film’s end, the apocalypse of the cinematic narrative is also colliding with the apocalypse of the cinematic apparatus, thus intensifying the affective impact from the film’s end, an intensification marked by von Trier in the extended moment of darkness and then silence before the credits begin. In other words, the diagrammatic dance of death not only depicts the eventual collision of the Earth’s trajectory with that of the planet Melancholia, but also depicts the collision or co-incidence of the trajectory of the film’s diegesis with its cinematic presentation, the apocalyptic collision that has been the condition of cinema from its inception.

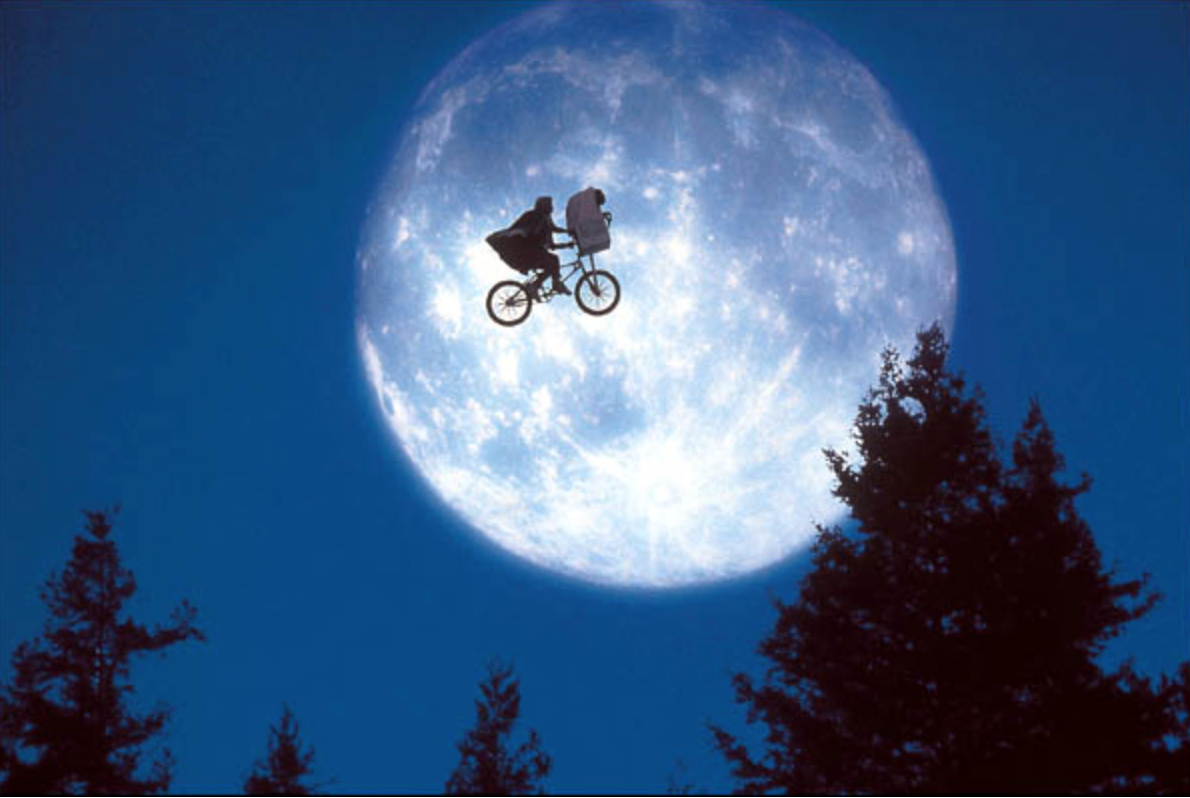

However, the diagram of the Dance of Death is not where von Trier chooses to end Melancholia but rather in the “magic cave” created for Leo and Claire by Aunt Steelbreaker (Leo’s pet name for Justine). Apparently something that Justine has materterally promised to build for Leo for years, the magic cave as it finally materializes takes the form of a teepee-frame made of branches, which Justine, Claire, and Leo occupy as the planet Melancholia makes its final approach towards the Earth and to the cinematic audience in the theater, in a shot that can’t help but call to mind Spielberg’s E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial (1982) (see Figures 10 and 11).

Shaviro’s detailed account of the affective and cinematic unfolding of the film’s final scene in relation to the “beautiful semblance” of Romanticist aesthetics is powerful and on point. But, in claiming that “In the final moments of Melancholia, everything is staked on a fantasy of primitivism when this fantasy is no longer able to operate,” he at one and the same time fails to see and lets us see how this “fantasy of primitivism” is another way to understand the film’s post-cinematic atavism. It is true, as Shaviro contends, that the “sense of comfort and protection” offered by the teepee “is entirely illusory” and that “the magic cave cannot actually avert the end of the world.” It is equally true that the magic cave cannot avert the end of the film—nor can any cinematic narrative device or turn. Indeed it is in its very failure to forestall the apocalypse built in to the temporal structure of the cinematic apparatus that the magic cave comes to stand, in the end, for cinema itself, in particular for von Trier’s post-cinematic atavism. Not only does the magic cave allude to the magical cinema of Méliès, but the very phrase recalls the pre-cinematic medium of the magic lantern,[2] whose technology is, I would suggest (see Figures 12 and 13), vaguely invoked in the scene in Part I when Claire’s husband John leads his guests in sending aloft paper lantern-style hot-air balloons covered with hand-written well-wishing messages for the newly married couple, which Justine then tracks with John’s powerful telescope.

But magic lantern shows, while precursors to theatrical cinematic projections, do not operate with the same apocalyptic temporality as does the mechanical apparatus of cinematic projection, which is in part why the film does not end with this episode of the magic of flight but rather with the episode of the creation and inhabitation of the magic cave. Shaviro does come close to accounting for the film’s atavism (without invoking the term) in his reading of the teepee scene at the end of the film and its longing for the primitivism of childhood: “The Child figures a fantasmatic future, just as the teepee figures a fantasmatic past. I think that both of these figures have such a poignant effect upon me—and upon so many other viewers of Melancholia—precisely because they are presented to us at the point of their abolition.” His account of the affective power of the child and the teepee points to what I have been calling the film’s post-cinematic atavism, the return or reemergence of past cinematic traits that are now endangered by or in jeopardy from cinema’s increased digitalization. Like the child and the teepee, then, cinema itself (particularly early photographic, theatrically projected cinema) is also presented to us at the point of its abolition. But in seeing the teepee as figuring a “fantasmatic past,” Shaviro misses, I would contend, the way in which the teepee figures the fantasmatic present of the cinematic experience itself. For just as the magic cave cannot avert the apocalyptic end of the world figured in the approach of the planet Melancholia, so the film Melancholia (or any other film) cannot avert the apocalyptic end of its diegetic world built in to the apparatus of cinematic creation and projection in the technical medium of celluloid film. Although we know when we enter the theater that the world being projected on the screen will end when the film does, that doesn’t prevent us, like Justine, Claire, and Leo, from entering the world of the film nonetheless. Thus it would not be going too far, I would argue, to say that the apocalypse that Melancholia is most concerned both to avoid and to preserve is the apocalypse of cinema itself.

Works Cited

Bolter, Jay David, and Richard Grusin. Remediation: Understanding New Media. Cambridge: MIT P, 2000. Print.

Grusin, Richard. “DVDs, Video Games, and the Cinema of Interactions.” Multimedia Histories: From the Magic Lantern to the Internet. Eds. James Lyons and John Plunkett. Exeter: U of Exeter P, 2007. 209-221. Print. A version of this chapter is included in this volume.

—. “Post-Cinematic Atavism.” Sequence 1.3 (2014). Web. <http://reframe.sussex.ac.uk/sequence1/1-3-post-cinematic-atavism/>. Reprinted in this volume.

—. “Remediation in the Late Age of Early Cinema.” Early Cinema: Technology and Apparatus. Eds. André Gaudreault, Catherine Russell, and Pierre Véronneau. Lausanne: Payot, 2004. 343-60. Print.

Gunning, Tom. “An Aesthetic of Astonishment.” Viewing Positions: Ways of Seeing Film. Ed. Linda Williams. New Brunswick: Rutgers UP, 1995. 114-33. Print.

—. “The Cinema of Attraction: Early Film, Its Spectator and the Avant-Garde.” Wide Angle 8.3-4 (1986): 63-70. Print.

Kara, Selmin. “Beasts of the Digital Wild: Primordigital Cinema and the Question of Origins.” SEQUENCE: Serial Studies in Media, Film and Music 1.4 (2014). Web. <http://reframe.sussex.ac.uk/sequence1/1-4-primordigital-cinema/>.

Leigh, Danny. “Lars von Trier Collides with the Hollywood Blockbuster in Melancholia.” Guardian. 30 Sept. 2011. Web. <http://www.theguardian.com/film/filmblog/2011/sep/30/lars-von-trier-melancholia-hollywood>.

Seitler, Dana. Atavistic Tendencies: The Culture of Science in American Modernity. Minneapolis: U of Minnesota P, 2008. Print.

Shaviro, Steven. “Melancholia, or, The Romantic Anti-Sublime.” Sequence 1.1 (2012). Web. <http://reframe.sussex.ac.uk/sequence1/1-1-melancholia-or-the-romantic-anti-sublime/>.

—. Post-Cinematic Affect. Winchester: Zero, 2010. Print.

Taubin, Amy. “Naught So Sweet.” Artforum 50.2 (2011): 71. Print.

Notes

This essay was previously published in SEQUENCE: Serial Studies in Media, Film and Music, 1.3, 2014 and is reprinted here with permission.

[1] See Dana Seitler’s Atavistic Tendencies. Seitler sees atavism as marking the temporality of modernism, as a form of temporal modernity. Shaviro argues that “von Trier himself is very much of a modernist, and thereby an adherent of all the values that he criticizes in Melancholia” (“Melancholia”). For Shaviro, though, von Trier’s modernism in Melancholia differs from that of his some of his earlier films: “Above all, von Trier’s own modernism is expressed in his continual attempts to create shock and scandal. Melancholia is the only of his films not to display what Taubin calls his ‘compulsive épater les bourgeois streak’” (citing Amy Taubin). Shaviro continues: “It often feels to me as if von Trier were stuck in the phase of adolescent boyhood. Or else, perhaps, he is caught in the grip of a compulsion to repeat the primal scene of early-20th-century modernism’s confrontations with outraged audiences.” My point would be that Melancholia, too, is modernist in its atavism, even if it avoids some of the stylistic traits of his earlier films.

[2] Some good examples may be viewed online at San Diego State University’s online exhibit of their Peabody Magic Lantern Collection here: <http://library.sdsu.edu/exhibits/2009/07/lanterns/index.shtml>.

Richard Grusin is Professor of English at University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, where he directed the Center for 21st Century Studies from 2010-2015. His work concerns historical, cultural, and aesthetic aspects of technologies of human and nonhuman mediation. With Jay David Bolter he is the author of Remediation: Understanding New Media (MIT, 1999), which sketches out a genealogy of new media, beginning with the contradictory visual logics underlying contemporary digital media. Culture, Technology, and the Creation of America’s National Parks (Cambridge, 2004), focuses on the problematics of visual representation involved in the founding of America’s national parks. Premediation: Affect and Mediality After 9/11 (Palgrave, 2010), argues that socially networked US and global media work to pre-mediate collective affects of anticipation and connectivity, while also perpetuating low levels of apprehension or fear. Most recently he is editor of The Nonhuman Turn (Minnesota, 2015) and Anthropocene Feminism (forthcoming Minnesota, 2016).

Richard Grusin, “Post-Cinematic Atavism,” in Shane Denson and Julia Leyda (eds), Post-Cinema: Theorizing 21st-Century Film (Falmer: REFRAME Books, 2016). Web. <https://reframe.sussex.ac.uk/post-cinema/5-3-grusin/>. ISBN 978-0-9931996-2-2 (online)