BY BRUCE ISAACS

Between 2001 and 2013, Alfonso Cuarón, working in concert with long-time collaborator, cinematographer Emmanuel Lubezki, produced several works that effectively modeled a signature disposition toward film style. After a period of measured success in Hollywood (A Little Princess [1995], Great Expectations [1998]), Cuarón and Lubezki returned to Mexico to produce Y Tu Mamá También (2001), a film designed as a low-budget, independent vehicle (Riley). In 2006, Cuarón directed Children of Men, a high budget studio production, and in March 2014, he won the Academy Award for Best Director for Gravity (2013), a film that garnered the praise of the American and European critical establishment while returning in excess of half a billion dollars worldwide at the box office (Gravity, Box Office Mojo). Lubezki acted as cinematographer on each of the three films.[1]

In this chapter, I attempt to trace the evolution of a cinematographic style founded upon the “long take,” the sequence shot of excessive duration. Each of Cuarón’s three films under examination demonstrates a fixation on the capacity of the image to display greater and more complex indices of time and space, holding shots across what would be deemed uncomfortable durations in a more conventional mode of cinema. As Udden argues, Cuarón’s films are increasingly defined by this mark of the long take, “shots with durations well beyond the industry standard” (26-27). Such shots are “attention-grabbing spectacles,” displaying the virtuosity of the filmmaker over and above the requirement of narrative unfolding. While the long take has fascinated (and continues to fascinate) numerous filmmakers working within and beyond the mainstream, Cuarón is unique in modeling the long take as foundational to his filmic method. Although Andrei Tarkovsky, Martin Scorsese, and Nuri Bilge Ceylan have repeatedly and imaginatively explored the aesthetic capacity of the long take in their work, I argue that none can be designated “long take” filmmakers in the sense that I employ the concept here. Brian De Palma, one of the great long take directors, who frequently utilizes the Steadicam to track the complexity of space, is also a great exponent of expressive montage (Martin). I thus distinguish Cuarón (and Lubezki as cinematographer) precisely because their aesthetic disposition is founded upon the effect of space and time uninterrupted by a conventional cinematic cut. This is a long take style that, as Bazin once argued of the neorealist filmmakers, confronts the aesthetic limitation of a contemporary normative editing system (Bordwell, “Intensified Continuity” 16-28). Against this normative model, Cuarón’s and Lubezki’s overarching long take style is quite idiosyncratic.

The long take serves a number of philosophical and aesthetic functions in film studies discourse. The desire for realism, the mark of the pro-filmic event, experiential immersion in the diegetic world, and spectatorial ambiguity have all filtered through competing discourses surrounding precisely what constitutes the long take (Bazin, “Evolution” 23-40; Rombes 38-40). In an image-based medium built on discrete sections of time, the radical artificiality of the medium is perceptually normalized through classical montage, which serves a very particular spatial and temporal regime. We see the harmony of spatial and temporal arrangement quite literally through montage; montage is in this sense a revelation of that which is otherwise hidden from view, the diegetic “whole.” In contrast, the long take, in its objection to the perceptual harmony of classical montage, manifests as an image of what Kristin Thompson has called “excess” (“Cinematic Excess” 513-24). The shot of marked duration exceeds not only the perceptual orientation of montage, but manifests its stronger, potentially more transgressive mark of excess in its unwillingness to conform to a generalized spectatorial regime. The long take is frequently, and certainly for Cuarón and Lubezki, a liberation from the constrictive spatial and temporal regime of tradition. The further Cuarón and Lubezki shift into the montage regime of contemporary Hollywood studio filmmaking, the more emphatic their subsequent departure from an aesthetic of classical montage.

Following what Cuarón deemed the aesthetic failure of Great Expectations (McGrath), Y Tu Mamá También represents the formative development in the Cuarón/Lubezki signature collaboration. Long-take, hand-held camerawork with inconspicuous movement captures the harmonious relationship of objects within a single spatio-temporal field. Children of Men’s dystopian genre narrative is realized almost entirely in extraordinarily complex, highly visible movements synthesizing hand-held and Steadicam aesthetics; in fact, Cuarón opted for a hand-held apparatus fixed to the body of the operator, thus in a literal sense animated by both the central weight of the body and the peripheral, contingency-based animation of the hand (Frederick). Gravity’s spatio-temporal field of the image (in this article I focus on the 13-minute opening long take) is digitally constituted through a virtual apparatus increasingly divorced from the material presence of the body (both that of the screen performer and the camera operator), the embodied technology of the apparatus, and the spatio-temporal field of the pro-filmic environment. Each film, I argue, not only affirms an aesthetic and philosophical style founded on the long take, but represents Cuarón’s and Lubezki’s negotiation of the long take as a cinematographic signifier of transgression.

These questions of aesthetic style are, as Udden argues, also questions of meaning, or questions of intent. “What do these long takes imply?” (27). But further, why the long take over some other potentially transgressive montage regime, such as the radical discontinuity cutting in recent mainstream action cinema (Stork)? In this chapter, I want to ask, what is the ideological function of the long take in Cuarón’s work with Lubezki, particularly as the products of their filmmaking collaboration become increasingly popular and they are compelled to negotiate the aesthetic, commercial, and cultural space of global Hollywood? Cuarón’s sojourn in Mexico for Y Tu Mamá También was precisely that: a departure as a precursor to return. This return inserted him and Lubezki into the heart of mainstream studio production with Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban (2003), effectively amalgamating a radically distinctive aesthetic style with the franchise ethos of contemporary Hollywood. Children of Men (Universal) and Gravity (Warner Brothers) are examples of what Mirrlees has labeled the “global blockbuster,” productions of enormous scale calibrated to return a specific profit percentage on investment (5). Within the mainstream globalized Hollywood milieu, I argue that the long take resonates as ideology within a complex production and consumption network over and above pure style.

The negotiation of the contemporary studio system further implicates the production, distribution, and exhibition itineraries brought about by the “digital turn” (Runnel et al. 7-12). Y Tu Mamá También, shot in 2000 and exhibited through film projection, is in essence a “filmic” film, bearing that special imprint of the pro-filmic on film stock, materializing through celluloid and developing chemicals, and the movement/time of the film reel through a projector. Exhibited in digital form, the filmic material maintains a second-degree indexicality, an indexical relation once removed from the pro-filmic event but nevertheless maintaining that existential bond that Doane equates with indexicality (“Indexicality” 2). A film shot on film but screened digitally escapes the void of Rodowick’s digital cinema bereft of all indexicality, without that pro-filmic world of the past being present to the image. Fittingly for Rodowick, shooting digital but reprinting to film for exhibition “seems not to be able to return to digital movies the experience of watching film” (164). Children of Men, a digital “film” in terms of its compositional logic,[2] as well as in the more significant context of the digital’s non-indexical sign, contrives spatial and temporal regimes afforded by digital production and post-production technologies. As has been well documented, Children of Men’s magnificent long takes are in fact digital assemblages of discrete intervals comprising the “sequence shot”[3] we see on screen (Fordham 34; Udden 30-34); the sequence shot as a spatial and temporal designation is only appropriate, in its purest sense, to filmic technology. The concluding hand-held/Steadicam sequence that tracks Theo’s (Clive Owen) passage through the prison riot was captured in several discrete segments, and in two separate shooting locations. Cuarón was reluctant to reveal the digital compositional truth behind Children of Men (Udden 32) simply because the filmic long take is long (in the Bazinian sense) only if uninterrupted by a cut or an otherwise invisible digital interpolation.[4]

In Children of Men, the digital long take repackages the ontological basis and existential allure of the filmic long take. Cuarón takes great pains to ground this digital duration in a discourse of filmic realism. As Udden suggests, Cuarón sounds very much like Bazin when explaining his cinematographic style (27). In 2014, eight years after Cuarón’s obfuscation of the digital “truth,” the objection to its artifice seems almost passé; the digital long take is artificial only if its obverse, the filmic-indexical long take, maintains its allure. In Scorsese’s Hugo (2011), digitality’s discretized long take is celebrated as a composite captured on several sets, stretching time and space into a fantastic digital amalgam (Seymour). Gravity (2013), a film that required years of digital pre-production development, has set a new benchmark in demonstrating the radical non-filmic capacity of digital cinema to depict discretized duration. Almost a decade after Children of Men, who would experience Gravity’s long take as anything other than a digital image form? The contemporary spectator is increasingly aware of—and sensitive to—digital spaces and times. In fact, I would argue that digital duration is properly the experience of time (in the Bergsonian sense)[5] inflected through an awareness of digitality’s fundamental discretization. And this coming to self-awareness of “the digital” is part of what we might productively call, projecting from Bazin, the “aesthetic of digital realism”: an awareness of a spatial and temporal field exhibited as a digital “whole” (Brown 72).

Reading technology and style through an ideological lens recalls the series of articles (1971-1972) produced by Jean-Louis Comolli on a materialist mode of filmic analysis. Working against Bazin and Mitry, whom Comolli labeled idealist for ascribing to film a pure capacity for revelation, Comolli reads the evolution of film style as a function of the values, beliefs, and choices inherent in a hegemonic system: “Thus it is indeed an ideological discourse about (notably) the ideological place of cinematographic technique which the fixed syntagm ‘for the first time’ [Comolli is referring to Bazin’s and Mitry’s romance of film’s technological ‘first times’] incessantly maintains” (426). Film style and its evolution through technology, which has advanced in fits and starts since the late nineteenth century, is always already implicated in the question of why: why the long take, why now, when the long take as an existential recourse to the real seems so outmoded by a montage of (increasingly digitally interpolated) attractions? While Bordwell has very convincingly argued against Comolli’s own ideological reading of cinematographic style (On the History of Film Style 159-163), still, Comolli’s desire for a materialist criticism of style is surely shared by all who wish to understand the implications of a mode of cinematography emerging through the industrial, commercial, and cultural apparatus of digital technology. I share Steven Shaviro’s position: “I really do love traditional cinematography, as has been provided by Chris Doyle for Wong Kar-wai, or by Gregg Toland for Orson Welles . . . But I still feel it is important to come to grips with the ways that cinematography is changing in response to 21st-century digital technologies” (“The new cinematography”). These “ways,” if I understand Shaviro correctly, are not only technological and aesthetic (for example, “new affordances provided by CGI”), but ideological, and thus profoundly implicated in how contemporary cultural meanings attach to new ways of contriving space and time in digital cinematographic images.

The index as the site of an essential filmic substance—the affecting present of a world past—is profoundly limited in a contemporary digital image regime. Of course, I acknowledge the allure of the indexical image-sign of cinema, or photography—for Barthes, the most provocative of all mediums (Camera Lucida 97-100). But to wish to recuperate the index as the substance of “cinema” essentially means excluding contemporary digital filmmaking from the category of the “cinematic”; the digital image would have to be something else, it would have to mean other things, affect us in non-cinematic ways. We see this rejection of digital cinema in mainstream filmmakers such as Christopher Nolan, Quentin Tarantino, and Martin Scorsese. This is Scorsese on the digital image increasingly pervasive in contemporary cinema production: “My big concern is that the image, ultimately, with CGI . . . I don’t know if our younger generation is believing anything anymore” (Side by Side). For Scorsese, belief in the image is founded upon the index’s imprint of a pro-filmic event—space and time materialized in filmic form. But beneath this desire for belief in the indexical sign is a more complex ideology underpinning the contractual relationship between the producers and consumers of mediated experience. Why must the spectator unproblematically believe in an image, or in the image’s primal relationship to the pro-filmic event? We might productively advance on Scorsese’s position to ask: in lieu of the affect of belief afforded by a filmic image, what forms of affective engagement are generated through the digital composition of a pro-filmic event? Even on a very basic iconographic and symbolic level, the digital sign points back to an object referent (Lefebvre and Furstenau 103-104). Where then, in lieu of the sacred relationship to the index, does the affective (and ideological) contract of the digital sign cohere as a meaningful image?

In attempting to read Cuarón’s and Lubezki’s ideology beneath a cinematographic style, I engage the image of the long take (whether filmic or digital) as a composition of material properties and processes: as an image of the materiality of the pro-filmic event, rather than the event in itself. I construe materiality less as index—that which is imprinted, preserved and unchangeable—than as the image-exhibition of a “nexus of finely interlaced force fields” (Highmore 119). In the most basic terms, applicable to the vast majority of contemporary image experiences, I argue that the materiality of the digital image is located in the capacity of digital technology to shape its itinerary, to take the pro-filmic event and materialize it anew within a digital image regime. When viewed as materialization (whether through rendering and compositing, or more radically through full image creation), the digital image is always already the materialization of the world: its physicality in space and time, as well as the “physical actuality of culture” (Highmore 119). Digital image materialization implicates the interlaced “force fields” of technologies of production, distribution, exhibition, and consumption; the evolution of a digital cinematographic style; and the spectatorial modes that confront contemporary audiences. The iPhone image (see Figures 1-2, below), digitally reincarnated here, bears the special affect of what Barthes called the photograph’s punctum. Like Barthes’s image, this casual capture of a time and place through an iPhone swells into the greater resonance of temporal experience—an experience of inhabiting that temporal moment. And yet, in contemplating this image within a fully digitized image environment (the iPhone image instagrammed), I no longer enter into a reverie situated in a hermetically sealed past, but rather, into a spatial and temporal network of undetermined image possibilities. Less than preserved past, the iPhone image affects the spectator as a discretized, infinitely dispersed whole.

The ontological foundation of the digital image seems to me the special resonance of the pro-filmic world as a series of material signs in transition: the physical ephemera of the world captured in an image, and then the affective potential of such ephemera on the spectator. In recent affect-based theory, the viewer’s body is privileged as the site of this material encounter; this is the embodied spectatorship of Sobchack (Carnal Thoughts) and Rutherford (What Makes a Film Tick), among others. But in my use, in the specific context of the digital sign, material also connotes the materiality of pro-filmic time and place (a historical actuality) and all it encompasses—the substance of an always already ideological whole. My approach here follows Dudley Andrew’s recent work in What Cinema Is! (2010), in which he rejects the value-based distinction between a filmic and digital cinematographic mode. Andrew suggests that “cinema must press forward into the new century, by taking into itself the subject matter that surrounds it, increasingly a new media culture” (94; my emphasis). I attempt to reveal digital cinema’s “taking into itself the subject matter that surrounds it,” focusing on the myriad ways in which new cinema materializes the world as a digital construct.

Beyond the Indexical: Y Tu Mamá También and Children of Men

Cuarón and Lubezki employ several different kinds of long takes across Y Tu Mamá También, Children of Men, and Gravity, and indeed, within each film. Y Tu Mamá También uses a plethora of what Peter Bradshaw calls “unobtrusively long takes.” In the opening sequence in which we’re introduced to Tenoch (Diego Luna), one of the film’s protagonists, the camera moves freely within a single room, holding the action long after the spectator has anticipated a cut. The camera is imbued with the capacity to move where it chooses, to depict background and foreground in concert, to erase the traditional perspectival hierarchy of the object’s relation to the spatial field. The frame is held in a medium-long shot, yet it is never stable; it is never an objective shot depicting the narrative action of a sequence. Captured entirely with a hand-held apparatus that jitters with the movement of the body and hand of the operator, the long take evinces the indexical relationship to the pro-filmic event (the camera operator is shooting film), but here, as in many of the spatial environments that constitute Y Tu Mamá También, the technology of film is not the ontological basis of “integral realism” (Bazin, “The Myth of Total Cinema” 21). Cuarón’s film certainly approximates the neorealist style through long takes and depths of field, but in this instance the Bazinian real is less a matter of indexicality than of a materialization of the real within an image. Surely what Bazin desired in the style of the filmmaker, whether Welles or Renoir or Rossellini, was an ethical commitment to depicting the material properties of the real; and as such, materiality was part of both “the real,” and an “aesthetic of reality” (Bazin, “An Aesthetic of Reality”). Realism in Y Tu Mamá También is less a matter of an a priori real than the materiality of a physical environment: the bodies on the bed, the background space of the room and its contents, the contents of the receding room beyond, all contained harmoniously in a freely accessible, densely populated space. The long take and emphatic presence of the hand-held apparatus intensifies the materiality of place, time, and a spectatorial subjectivity within the pro-filmic environment.

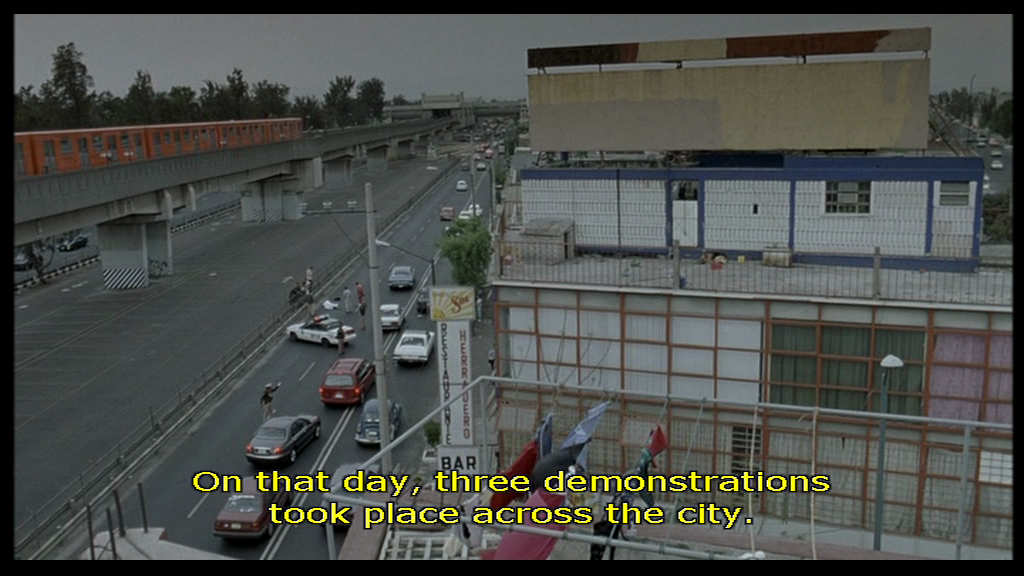

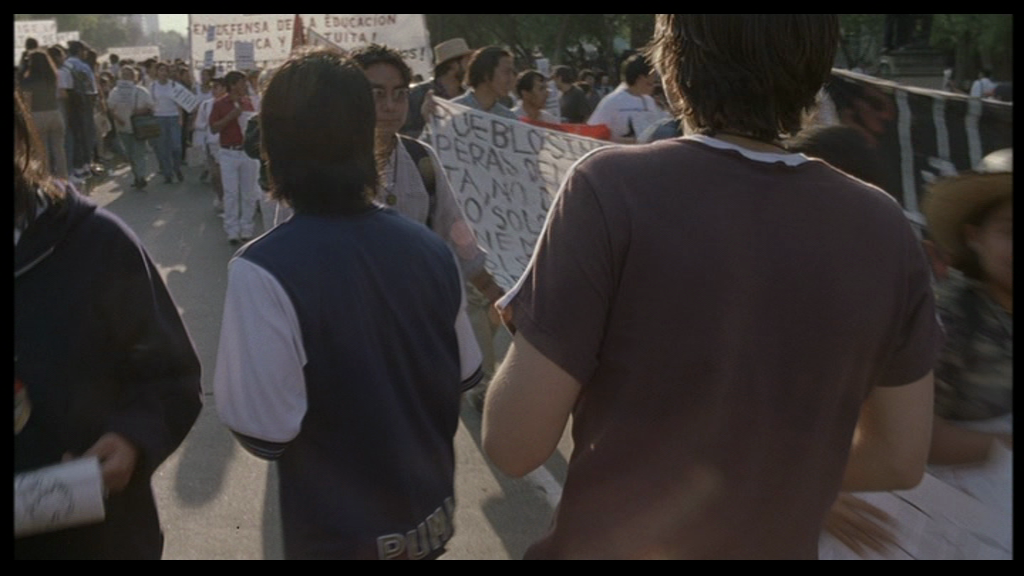

Y Tu Mamá También’s story about border crossing and transgression is depicted in several sequence shots that expand the purely physical pro-filmic event to encompass a wider historical/political milieu. Julio (Gael García Bernal) and Tenoch literally pass through a transformational moment in Mexican political history (evincing a generational apathy that Cuarón seems to be criticizing) by seeking out car keys from Julio’s sister at a demonstration. While the boys are unconcerned with the political exigencies, the hand-held camera is granted access to a complexly integrated spatial field, dissociating from the narrow perspective of the protagonists to reveal a diversely articulated mass of protesting bodies (Figures 3-5, below). The camera encompasses separate narrative frames—the boys’ ensuing road trip and the political demonstration—within a spatial and temporal whole, moving between the two without encumbrance. This sequence demonstrates Cuarón’s aesthetic of the long take as a form of spatial revelation. Foreground and background, rather than discrete frames within a traditional perspectival hierarchy, materialize as a physical and “acculturated” whole. Captured in duration through the hand-held camera, fixed in its movements to the body of the operator and increasingly drawn to the crowd, political history and its subject materialize within the diegesis, implicating the road-trip narrative as merely one (and not necessarily the primary) affective field. This long take strategically documents a narrative diegesis while revealing a historical past that is now made present to the spectator.

History’s materiality—what Žižek refers to as the “background” of the frame—is emphatically foregrounded in the use of the long take in Children of Men. The shot of excessive duration is now more elaborate and challenging, and more overtly situated as Cuarón’s and Lubezki’s signature cinematographic style. Unlike the image of duration captured and exhibited through filmic material in Y Tu Mamá También, in Children of Men Cuarón employs what I refer to as a digital compositional logic. Freed from the burden of an indexical mapping of the pro-filmic environment, this image materializes the “nexus of finely interlaced force fields” (Highmore) in increasingly impossible temporal stretches. The opening long take is succeeded by the astonishing complexity of a car chase captured through a “doggie-cam” (Fordham), which is bettered again in the final act in one of the most complex and awe-inspiring sequence shots in cinematic history (Frederick).

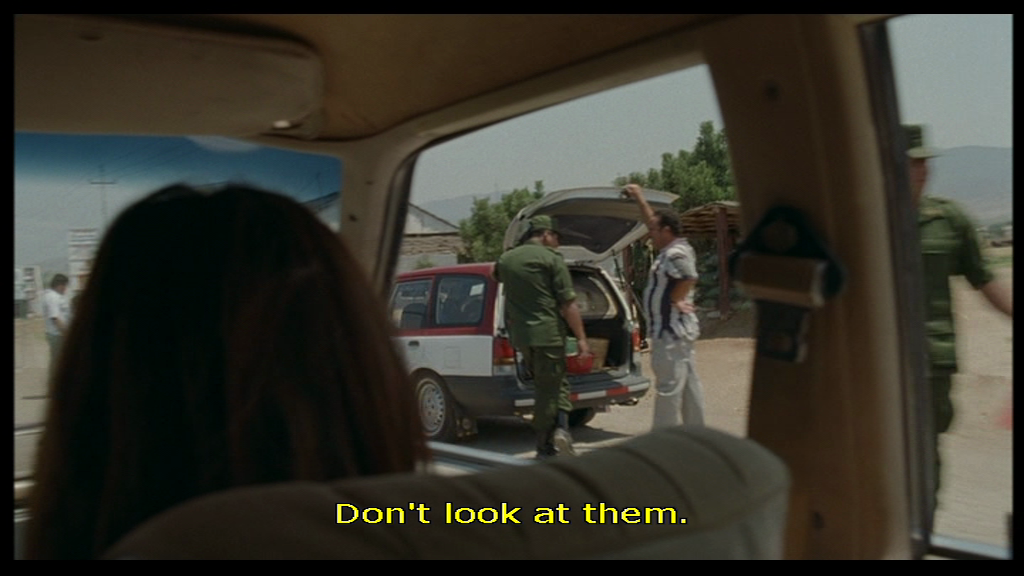

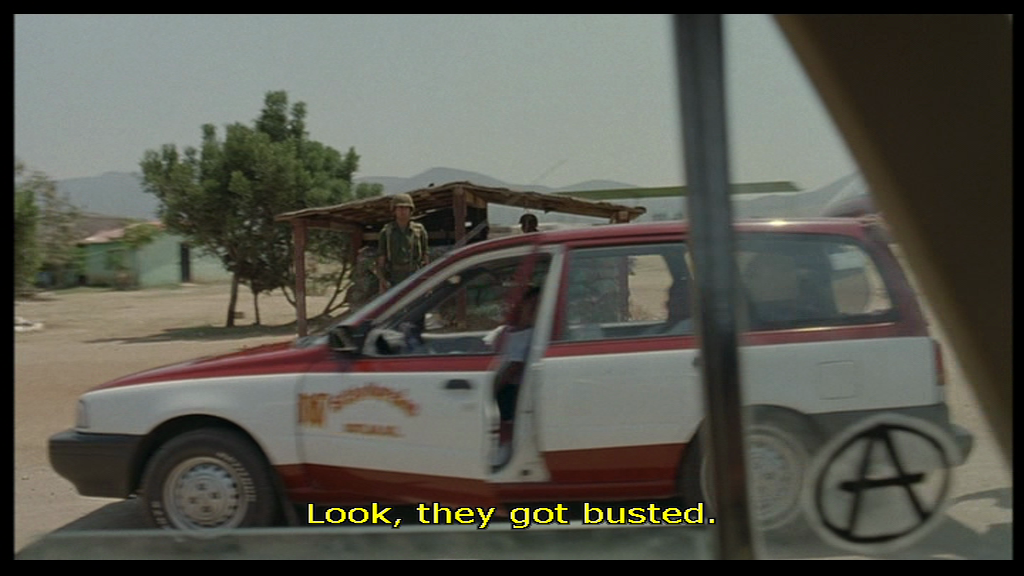

Referring to the conventional quest narrative of Children of Men, Žižek suggests that “the true infertility is the very lack of a meaningful historical experience . . . And it is clear that the true, most radical impact of global capitalism is that we lack this basic, literally, world view, a meaningful experience of totality.” This encompassing of a world viewed in its totality is clearly one of Cuarón’s aesthetic motivations in both Y Tu Mamá También and Children of Men. The long take reveals a material reality that is grounded in the meaning of a totalized historical experience. In Y Tu Mamá También, an innocuous long take covering a busy dialogue exchange in a car suddenly departs from the narrative foreground to depict a pictorial background: a police roadside stop victimizing a group of locals, symbolic of a wider, long-practiced, and endemic social repression of the individual (Figures 6-9). Such political “backgrounds” are steadfastly present in Y Tu Mamá También, but it is the casualness of the hand-held gaze, in even more casual duration, which need not fixate on this brief interruption to the narrative, that is most striking as a depiction of historical experience. And Cuarón’s historical snapshot is not a discrete historical event. Rather, a materialist analysis reads this history as process, as encompassed within a process of becoming. Thus, the sequence shot—that does not cease in its revelation of the pro-filmic world simply because it is cut from the field of vision—materializes also as the constant evolution of historical forces. The image speaks to both past and future, internal to Mexico’s national context, while speaking outwardly toward the threat of a globalizing “ideological despair of late capitalism” (Žižek). Ironically, 20th Century Fox (Mexico) distributed the film, which recouped 40 million dollars worldwide on an art-house budget of 5 million, in part paving the way for Cuarón’s and Lubezki’s return to Hollywood.

I argue that in Children of Men, with Cuarón and Lubezki now filtering the image through a digital production apparatus, time and space are even more emphatically material concerns. The human world is dying as women are infertile; the environment no longer has the capacity to replenish itself; state apparatuses are totalitarian and repressive. Within this globalized dystopia, Theo wears a jacket that celebrates a utopian past-time of the London Olympics 2012, still six years away during the film’s production. The image of a future-historical event functions both as a glib joke about the contemporary fetish for empty (globally produced and consumed) spectacle, and as an image of a lost utopia, registering quite literally for Theo and the spectator as “loss.” In 2027, a dystopian London is revealed through the material detritus of a diseased city: a hierarchical and class-conscious place where refugees line streets in cages, environmental degradation is pervasive, and garbage is strewn openly in public space. The opening long take (a set of two discretized digital durations) first follows Theo, then freely dissociates from its primary object (the film’s protagonist) and displays the world as a background encapsulating narrative foreground. The image of the city, seen through the gaze of an autonomous apparatus, is neither an image of attraction nor a narrative cue; it is, merely, the revelation of the materiality (physical/historical/ideological) of a London city street in the near, though very recognizable, future.

It is clear when viewing Y Tu Mamá También and Children of Men through a materialist lens that each film demonstrates a profound ethical commitment to depicting a material historicity. Cuarón’s depiction of road trips in both films demonstrates a desire to recuperate history as the experience of subjectivity and difference. This ethical commitment to the material real is surely greater than any ontological field founded upon an indexical relationship between object and image. Indeed, I would go so far as to say that digital cinematographic and editing practice presents the technology to more emphatically represent materiality. And in a world in which digital code contaminates, and then gradually subsumes, analogical form, paradoxically, the world as historical materiality becomes all the more alluring, all the more affecting. Of course, Manovich has convincingly demonstrated the logic of Vertov’s filmic image that exceeds the real. In revealing what is hidden from the subjective gaze, Vertov’s technological image exceeds the world viewed through the subjective senses, exhibiting the cinematographic world as more than the world the spectator inhabits (293-308). But for all of Manovich’s ingenious argument for the analogy between Man With A Movie Camera and the contemporary digital moment, Vertov was nevertheless constrained by the all-encompassing technology of celluloid. He was shooting film and cutting frenetically within the material parameters of that medium. Following Elsaesser and Hagener, I argue that in the emergence of cinema as a digital image itinerary, the materiality of the pro-filmic event is potentially intensified through “its re-embodied manifestation of everything visible, tactile and sensory” (174). The digital image, in effect, potentially re-materializes the world in image form.

A Mark on the Digital Lens

In my reading of Children of Men, materiality registers as a non-indexical image phenomenon. Of course, my desire for a material real and its historical totality clearly recuperates a Bazinian realist myth. Yet in the era of what Shaviro has already called “post-cinema” (Post-Cinematic Affect) we increasingly need new ways to conceptualize the material real through an experience of non-indexical signs. We have to find new ways of living with images.

One such new way of being with the digital image materializes in the bravura sequence shot in the final act of Children of Men. To begin, we must give up our desire for the ontological and existential plenitude of duration: Cuarón and Lubezki efface a series of cuts from the spatial environment, compositing separate image durations as a singular spatial and temporal whole. Theo, Kee (Clare-Hope Ashitey), and her newborn baby flee Bexhill prison as a riot breaks out. Within the diegesis, the riot serves as precursor to a future national, and potentially global, revolution. Cuarón and Lubezki frame the escape in a long take captured in what I will call the embodied hand-held apparatus, fixed to both the hand and body of the operator. The camera follows Theo for the duration of the sequence, but here again, as in the hand-held aesthetic in Y Tu Mamá También, the apparatus in its radical autonomy within the environment exceeds both the eye of the protagonist and the traditional viewing subject. At 1:26:32,[6] midway through the sequence shot, blood (a broken squib) splatters onto the lens of the camera. Apparently Lubezki or the operator called “cut” to reset for the next take (Frederick). In filmic-indexical terms, the marking of the lens constitutes an ontological rupture; the natural impulse is therefore to cut—to cut that section away—and reconstitute the insularity of the pro-filmic event. But the sequence shot was not cut, Clive Owen and the other actors remained oblivious to what had happened, and the action continues with blood clearly showing on the lens.[7]

The mark on the lens is not a mark of “the digital itinerary” per se; such ruptures in the diegesis, while uncommon, occur in celluloid production. For example, in the opening sequence of Saving Private Ryan (1998), Spielberg’s documentary style encompasses this ontological slippage between diegetic and non-diegetic apparatus (Figures 10-11). But Spielberg’s marks are carefully choreographed, and indeed, rationalized by a reduced color ratio in the image, hand-held camerawork, and frenetic discontinuous cutting. In my viewing of Saving Private Ryan, the affective encounter with the mark on the lens occurs within a clearly articulated, highly formulaic visual and aural style. Spielberg’s mark on the lens is displaced to a generalized location within the diegesis, the arrival at Omaha Beach. The affect of the mark thus resonates within a generic historical field and its well-trodden, familiar representational aesthetic. In displacing the mark from the frame to the diegesis, Spielberg’s image renders the apparatus again invisible, and strategically subdues the potential transgression of the ontological rupture.

But consider the radical difference of the mark on the lens in Children of Men. First, in the Cuarón-Lubezki sequence shot, the mark appears accidentally, at 1:26:58 (Figures 12-13, below). The pro-filmic event is marked through what Doane has called “contingency,” a spontaneous opening up of a field of “the new” (Emergence 100); in spontaneously opening into the pro-filmic environment, the mark re-materializes that environment. Second, unlike Saving Private Ryan’s mark, which is choreographed within a complex montage itinerary (a montage of distraction!), in Children of Men, the mark is subjected to the weight of its own duration: the diegetic/non-diegetic rupture is held for 1 minute and 18 seconds before its erasure through a digital splice. The curious affect of this mark incorporates the base materiality of the pro-filmic environment (physical matter marking the lens, and in turn materially marking the physical environment), as well as the discretized nature of the digital mark as a spontaneous irruption within the pro-filmic field. Discretization—the material logic of digitality—could in this sense be construed as an infinite field of “marking the real,” reconstituting the pro-filmic environment through production and post-production processes. The impulse to cut for director or cinematographer is thus weakened, and the digital mark in duration instead opens onto new and potentially richer ways of accessing the pro-filmic event.

Cuarón could have removed the mark by searching for that one perfect take. But why search for an indexical sign—the sign of the uncontaminated real—in an era of discretized image production? He could have removed the mark in digital post-production. But again, why erase the mark when leaving it within the frame merely re-materializes the pro-filmic environment, when it is merely one further adornment of a wonderfully rich digital cinematic background? In its open display within the frame, the mark on the lens in Children of Men is precisely not an ontological rupture, but a symptom of the logic of digital discretization.

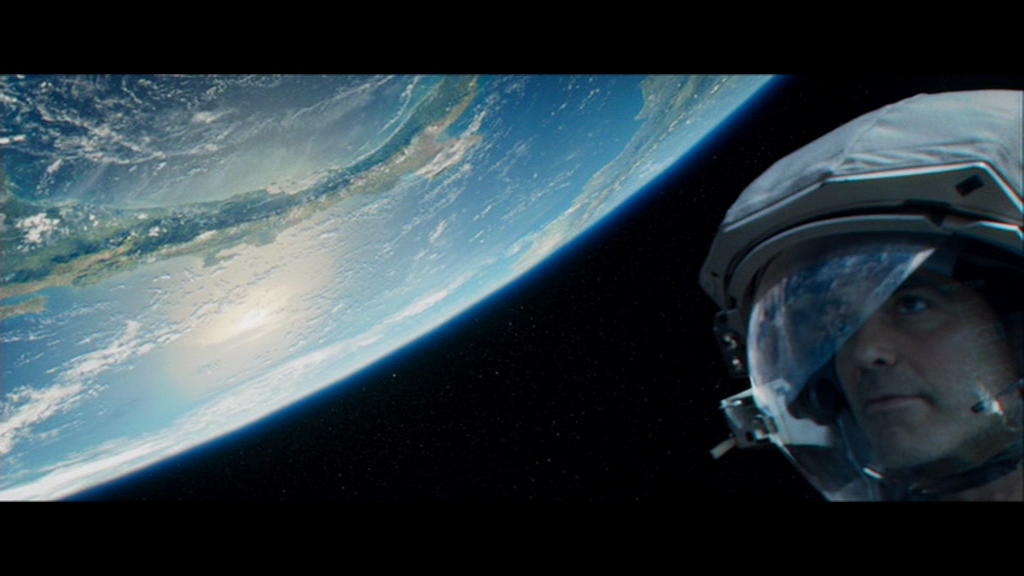

Abstraction and Virtuality in Gravity

In this article, I have read the long take as a material phenomenon, shifting in its aesthetic register freely between film and digital technologies of production and consumption. Materiality connotes the actuality of a place and time, as well as what Highmore has called the “interlaced force fields” that emanate from it. In concluding this reading, I turn to the opening 13-minute sequence shot of the most critically praised Cuarón-Lubezki collaboration, Gravity. In contrast to much of the critical reception of Gravity, I argue that the dominant image of the film’s spatial field is not that of the unfathomable depths of space—and certainly not the kind of threatening spatial void conventional in the science fiction genre. Rather, the center of Gravity’s sequence shot is the Earth, the gloriously simulated globe in a constant virtual rotation. While the field of the shot incorporates several discrete narrative frames—Lieutenant Kowalski’s (George Clooney) spacewalk, Dr. Stone’s (Sandra Bullock) work on the Hubble telescope, Engineer Shariff’s actions in the background[8]—each frame is composed only to subsequently reframe into a strategic revelation of the digital globe. Such strategic re-framings occur at 7:40-7:48 and 8:25-8:55.[9] At 8:25, Kowalski turns from Stone to gaze upon the Earth: “You’ve gotta admit one thing: you can’t beat the view.” It is an awestruck murmur in contemplation of nature’s sublime image of the world (Figures 14-16).

A number of very interesting cinematographic signs are deployed here. Kowalski not only gazes up at the Earth, but the resplendent image is reflected in the glass of his helmet, presenting a doubling of the object. Cuarón makes this doubling emphatic through a continuity trick: the eye of the virtual camera begins on Kowalski, moves left to right, relegating Kowalski to off-screen space, only to pick up Kowalski again, now at the right of screen. Kowalski’s repositioning occurs without a cut in the image, revealing the discombobulating multi-directionality of zero gravity space. In this movement of the cinematographic eye, the Earth is both an image in itself and the reflection of a subjective gaze; we see and, simultaneously, see ourselves seeing. There are several ways we might read the affect of this doubled spectatorship. On the one hand, the Earth becomes an autonomous object, a spectacle image divorced from the operation of story and character, or indeed, a field of signification. It seems foolish to ask what this image means. Instead, as the eye moves from left to right, we encounter a spatial and temporal field of revelation, nature’s impossible image. This is Kowalski’s view, which is literally the object of his seeing. But in its doubling through a digital effect—the object as reflection—the Earth signifies as an abstraction. The reflected Earth is an image of colors, contours, and textures, the virtuality of space, movement, and time, and less so the materiality of a planet and its people, or the aesthetic design of a God-creator. This is an Earth rendered in what Manovich might call the digital brushstroke, and as spectators we happily fetishize its discretized perfection. In the era of expanding virtual technologies of production, you can’t beat that digital cinematic view.

Gravity’s image of the Earth in this 13-minute sequence shot represents a paradigmatic transformation of the long take cinematographic style utilized in Cuarón’s and Lubezki’s earlier films (Bergery). Consider what I have called the materiality of the long take in Y Tu Mamá También and Children of Men alongside the following description of Gravity’s virtual cinematography:

The only real elements in the space exteriors are the actors’ faces behind the glass of their helmets. Everything else in the exterior scenes—the spacesuits, the space station, the Earth—is CGI. Similarly, for a scene in which a suit-less Stone appears to float through a spaceship in zero gravity, Bullock was suspended from wires onstage, and her surroundings were created digitally. (Bergery)

Digital “surroundings” are not merely pictures, but entire image fields composed of movement and time. Thus, the image of the Earth in rotation encompasses not only that image as a pictorial form (colors, textures, shapes, etc.), but more significantly, the image animated in relation to material bodies within the frame. In the digital duration of Children of Men, I argued that the digital splice in fact presented an emphatic materiality of a physical and acculturated world in excessive duration. In each of Children of Men’s sequence shots, Theo’s body is a material object within the discretized duration, affecting his environment while also being affected by it. The cuts are obfuscations only in an image regime desiring an indexical bond with the pro-filmic environment, which the digital image itinerary clearly does not. But in Gravity, the affect of the body (whether Stone’s/Bullock’s, or what I will refer to as the body of “The Earth”) is toward inertia, a mode of suspension within the animation of a digital surrounding. The relatively inactive body (at least within a wider spatial and temporal field), rather than the site of embodiment, that is, infused with the body’s capacity to affect its material surroundings, is background to the foreground of a virtual image field. Visual Effects Supervisor on Gravity, Tim Webber, explains, “we created a virtual world and then worked out how to get human performances into that world” (qtd. in Bergery). In contemporary virtual cinematography—nowhere more brazenly deployed than in Gravity—digital surroundings significantly affect the material body and its capacity for articulation, while the affect of the material body is significantly diminished.

The paradigmatic transformation in contemporary digital cinematography is toward the virtual apparatus and its unique cinematographic properties, increasingly a foundational part of high budget production. The desire among a great deal of contemporary filmmakers, Cuarón and Lubezki included, seems to be for “complete dimensional freedom,” or what is described as “true space operation” (Bergery). Mike Jones argues quite similarly of virtuality’s “pure and unique cinema . . . [that] delivers an experience that is cinematically autonomous, [and] unable to be obtained from any other art form” (242). But surely virtuality does not configure spatial freedom as much as spacelessness, or a virtual field without material properties. I read Lubezki’s notion of “truth” (Lubezki, qtd. In Bergery) as the expression of a category of the real and its materialization in space and time. There is nothing new here in the desire for the foundational “truths” of space. In the early 1920s, Murnau had already imagined

[t]he fluid architecture of bodies with blood in their veins moving through mobile space; the interplay of lines rising, falling, disappearing; the encounter of surfaces, stimulation and its opposite, calm; construction and collapse; the formation and destruction of a hitherto almost unsuspected life; all this adds up to a symphony made up of the harmony of bodies and the rhythm of space; the play of pure movement, vigorous and abundant. All this we shall be able to create when the camera has at last been de-materialized (qtd. In Eisner 18).

Murnau sounds very much like a champion of new virtual cinema, with its de-materialized environments and apparatus. Except, in Murnau, mobile space is not virtual space. Mobile space affects—and is affected by—bodies. Mobile space reveals “the formation and destruction of a hitherto almost unsuspected life.” Murnau’s de-materialized apparatus opens into a “harmony of bodies” in perfect and permanent mobility. Murnau’s mobile space is thus a revelation of the materiality of the body and its relationship to a material environment.

But against the desire for the materiality of mobile space that surely gave rise to the first camera movements in the late 19th century, to tracking and dolly shots, to the crane movement, the Steadicam and hand-held cinematographic devices—the purely virtual space encompasses the digitally animated frame as well as the material relationship between the frame and the real bodies situated within it. Virtual backgrounds move; virtual backgrounds act upon bodies, situating them, affecting them. Space and time in the virtual environment are strategically calibrated to move around the body, creating an illusion of zero gravity, or discombobulating directionality. Light animated through pre-visualization within a virtual digital environment affects the “naturalistic light on the faces” of actors (Lubezki, qtd. in Bergery), and so on. The unique affect of virtual space is, as Mike Jones suggests, “rooted in a depiction of fantasy and the impossible” (236), depicting bodies in a field of movement and time bereft of the material affect of “the body.”

Kristin Thompson’s recent essay on Gravity emphasizes its “strong classical story” that privileges “excitement, suspense, rapid action, and the universally remarked-upon sense of immersion alongside the character” (“Gravity—Part 1”). I agree with Thompson here: alongside its paradigm-shifting virtual cinematography, Gravity is an astonishingly formulaic narrative film. In Stone’s “rebirth after despair” (Cuarón, qtd. in Thompson, “Gravity—Part 1”), the spectator encounters conflict (physical, emotional, and existential—the inciting incident occurs precisely when it should, at the 9-10 minute mark) and undergoes a series of neatly calibrated trials to deal with that conflict. The journey toward home and mastering the trauma of the past (the death of a child is especially affecting) articulates with great clarity the reconstruction of the individual common to mainstream American cinema. Stone’s character arc is therefore toward groundedness, and the reassurance that all is well again.

Within this narrative field, I read Gravity’s ideological subtext as the rebirth of a subject in relation to a newly realized virtual image of the Earth. Implicated in this ideology of self and world is a technological evolution in cinema production that has fundamentally altered the medium of moving images; this is an Earth recreated through a virtual apparatus. Mirrlees is thus correct to read the contemporary global blockbuster as an integrated production and consumption mode (7-10). Virtuality is a high-end production field attached to new modes of digital image creation and consumption. In such high-end productions, virtual cinematography has rolled out through the industrial and commercial mechanisms of contemporary American studio practice, and it is thus part of a wider economy of contemporary Hollywood and its hegemonic dominance of global cinema cultures.

What is this view of the Earth, that so astonishes Kowalski and the spectator? De-materialized, spaceless and timeless, Gravity’s virtual Earth resonates as the image of what Henri Lefebvre called “abstract space.” This is contemporary global Hollywood’s virtual world object that seeks to “erase the felt or intangible distinctions between places . . . fragmenting space into sites of specific use in order to make it increasingly controllable and marketable” (Nick Jones, “Quantification and Substitution” 254). I have used the term “materiality” to refer in part to a mode of spatialized representation, the image that captures and represents the material “real.” Such spaces, which I argue are the basis of Cuarón’s and Lubezki’s cinematographic style in Y Tu Mamá También and Children of Men, constitute a field of “‘architectonic’ determinants . . . [in which] pre-existing space underpins not only durable spatial arrangements but also representational spaces and their attendant imagery and mythic narratives” (Lefebvre, The Production of Space 230; original emphasis). Following Žižek, I have argued that such places and times—a history as material process—open onto a “meaningful experience of totality.”

But Gravity is bereft of such historical processes. Historical place and time are virtualized as two convergent moving image simulations. First, we have Kowalski’s view of nature: de-historicized, de-materialized, disembodied. Kowalski’s virtual Earth exceeds our capacity to ground its materiality in an actual here and now, the here and now of Mexico City in Y Tu Mamá También or the dystopian London in Children of Men. Second, there is the Earth of Stone’s return, an ideal, utopian world upon which she is grounded. Intriguingly, Cuarón chooses to depict this Earth as a state of nature, a pristine, timeless land, as if encountered for the first time (Figures 17-18, below). The arrival simulates both a first encounter with the native, and the discovery of a pre-colonized world. In this encounter, Stone’s rebirth is precisely not materialized within a space as historical process, but within a utopian imaginary virtualized as an undifferentiated whole. This is a ground Stone encounters without people and cultures. I read this journey toward home and rebirth as the regeneration through conflict of a global (American) subject in a borderless, undifferentiated world. The virtualization of this world is made all the more emphatic, and all the more ideal, through the duration of the long take. As astonishing as it is in the opening sequence, duration—even digitality’s discretized duration—is merely one more virtual tool, one further simulated form within a de-materialized field.

The object of virtual duration for Cuarón and Lubezki seems to me part of a wider virtual image-rendering of global, capitalist space, which enables Hollywood to export its hugely popular narratives within a global cinema industry. In my reading of Gravity, “The Earth” bears the technological, aesthetic, and ideological signature of late capitalist American studio film production, “sustaining the global market dominance of Hollywood and its cross-border trade in blockbuster films” (Mirrlees 7).

Works Cited

A Little Princess. Dir. Alfonso Cuarón. Perf. Liesel Matthews, Eleanor Bron, Liam Cunningham. Warner Bros., 1995. Film.

Andrew, Dudley. What Cinema Is: Bazin’s Quest and Its Charge. Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell, 2010. Print.

Barthes, Roland. Camera Lucida: Reflections on Photography. London: Vintage, 2000. Print.

Bazin, André. “The Evolution of the Language of Cinema.” What Is Cinema? Volume 1. 23-40.

—. “The Myth of Total Cinema.” What Is Cinema? Volume 1. 17-22. Print.

—. What Is Cinema? Volume 1. Trans. Hugh Gray. Berkeley: U of California P, 1967. Print.

—. “An Aesthetic of Reality: Cinematic Neorealism and the Italian School of Liberation.” What is Cinema? Volume 2. Trans. Hugh Gray. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1967. 16-40. Print.

Bergery, Benjamin. “Facing the Void: Emmanuel Lubezki, ASC, AMC and his Collaborators Detail their Work on Gravity, a Technically Ambitious Drama Set in Outer Space.” American Cinematographer 94.11 (2013). Web. 15 Mar. 2014.

Bordwell, David. “Intensified Continuity: Visual Style in Contemporary American Film.” Film Quarterly 55.3 (2002): 16-28. Print.

—. On the History of Film Style. Cambridge: Harvard UP, 1997. Print.

Bradshaw, Peter. “Y Tu Mama Tambien.” The Guardian 12 Apr. 2002. Web. 28 May. 2014.

Brown, William. Supercinema: Film Philosophy for the Digital Age. Oxford and New York: Berghahn, 2013. Print.

Chitnis, Deepak. “We Don’t Talk Like That.” The American Bazaar 7 Oct. 2013. Web. 18 May 2014.

Comolli, Jean-Louis. “Technique and Ideology: Camera, Perspective, Depth of Field (Parts 3 and 4).” Narrative, Apparatus, Ideology: A Film Theory Reader. Ed. Philip Rosen. New York: Columbia UP, 1986. 421-43. Print.

Cuarón, Alfonso, Dir. Children of Men. 2006. 2-Disc Special Edition. DOP Emmanuel Lubezki. Perf. Clive Owen, Clare-Hope Ashitey, Julianne Moore. Universal, 2007. DVD.

—. Gravity 3D. 2013. DOP Emmanuel Lubezki. Perf. Sandra Bullock, George Clooney. Warner Bros. Entertainment Inc., 2014. Blu-Ray.

—. Y Tu Mamá También (And Your Mother Too). DOP Emmanuel Lubezki. Perf. Maribel Verdú, Gael García Bernal, Diego Luna. 20th Century Fox (Mexico), 2001. Film.

Denson, Shane, Therese Grisham, and Julia Leyda. “Post-Cinematic Affect: Post-Continuity, the Irrational Camera, Thoughts on 3D.” La Furia Umana 14 (2012): <http://www.lafuriaumana.it/index.php/archives/41-lfu-14>. Archived at: <http://bit.ly/1cAYgqy>. Web. 13 May 2015. Reprinted in this volume.

Doane, Mary Ann. The Emergence of Cinematic Time: Modernity, Contingency, the Archive. Cambridge: Harvard UP, 2002. Print.

—. “Indexicality: Trace and Sign: Introduction.” differences 18.1 (2007): 1-6. Print.

Eisner, Lotte H. Murnau. London: Secker and Warburg, 1973. Print.

Elsaesser, Thomas, and Malte Hagener. Film Theory: An Introduction Through the Senses. New York: Routledge, 2010. Print.

Fordham, Joe. “Children of Men: The Human Project.” Cinefex 110 (2007): 33-44. Print.

Frederick, Dave. “Children of Men—George Richmond. Bsc, Soc – 2012 Society of Camera Operators Historical Shot Award Recipient.” Vimeo 2012. Web. 17 Apr. 2014. <http://vimeo.com/40314279>.

Gravity. Box Office Mojo. Web. 8 Jun. 2014. <http://www.boxofficemojo.com/movies/?id=gravity.htm>.

Great Expectations. Dir. Alfonso Cuarón. Perf. Ethan Hawke, Gwyneth Paltrow, Chris Cooper. Warner Bros., 1998. Film.

Guerlac, Suzanne. Thinking in Time: An Introduction to Henri Bergson. Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Press, 2006. Print.

Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban. Dir. Alfonso Cuarón. Perf. Daniel Radcliffe, Emma Watson, Rupert Grint. Warner Bros., 2004. Film.

Highmore, Ben. “Bitter after Taste: Affect, Food, and Social Aesthetics.” The Affect Theory Reader. Eds. Melissa Gregg and Gregory J. Seigworth. Durham: Duke UP, 2010. 118-37. Print.

Hugo. Dir. Martin Scorsese. Perf. Asa Butterfield, Ben Kingsley, Sacha Baron Cohen. Paramount, 2011. Film.

Jones, Mike. “Vanishing Point: Spatial Composition and the Virtual Camera.” Animation 2.3 (2007): 225-43. Print.

Jones, Nick. “Quantification and Substitution: The Abstract Space of Virtual Cinematography.” Animation 8.3 (2013): 253-66. Print.

Joubert-Laurencin, Hervé. “Rewriting the Image: Two Effects of the Future-Perfect in André Bazin.” Opening Bazin: Postwar Film Theory and its Afterlife. Ed. Dudley Andrew, with Hervé Joubert-Laurencin. Oxford: Oxford UP, 2011. 201-05. Print.

Lefebvre, Henri. The Production of Space. Cambridge: Blackwell, 1991. Print.

Lefebvre, Martin, and Marc Furstenau. “Digital Editing and Montage: The Vanishing Celluloid and Beyond.” Cinémas: Revue d’Études Cinématographiques [Journal of Film Studies]. 20.1 (2011): 61-78. Print.

Man With a Movie Camera. Dir. Dziga Vertov. 1929. Film.

Manovich, Lev. The Language of New Media. Cambridge: MIT P, 2001. Print.

Martin, Adrian. “A Walk Through Carlito’s Way.” Lola 4 (2013). Web. 18 Jan. 2014. <http://www.lolajournal.com/4/carlito.html>.

McGrath, Charles. “A Circuitous Route to Outer Space: Alfonso Cuarón Discusses His Films.” New York Times 3 Jan. 2014. Web. 3 Jun. 2014. <http://www.nytimes.com/2014/01/05/movies/awardsseason/alfonso-cuaron-discusses-his-films.html?_r=0>.

Mirrlees, Tanner. “How to Read Iron Man: The Economics, Geopolitics and Ideology of an Imperial Film Commodity.” Cineaction 92 (2014): 4-11. Print.

Riley, Janelle. “Cuaron, Lubezki Talk Mistakes, Long Takes and How Peter Gabriel Made Gravity Possible.” Variety 13 Feb. 2014. Web. 2 Jun. 2014. <http://variety.com/2014/film/awards/cuaron-lubezki-1201102584/>.

Rodowick, David Norman. The Virtual Life of Film. Cambridge: Harvard UP, 2007. Print.

Rombes, Nicholas. Cinema in the Digital Age. New York: Wallflower, 2009. Print.

Runnel, Pille, et al. The Digital Turn: User’s Practices and Cultural Transformations. Frankfurt: Peter Lang, 2013. Print.

Rutherford, Anne. What Makes a Film Tick?: Cinematic Affect, Materiality and Mimetic Innervation. New York: Peter Lang, 2011. Print.

Saving Private Ryan. Dir. Steven Spielberg. Perf. Tom Hanks, Edward Burns, Matt Damon. Paramount, 1998. Film.

Seymour, Mike. “Hugo: A Study of Modern Inventive Visual Effects.” fxguide 1 Dec. 2011. Web. 8 May 2014. <https://www.fxguide.com/featured/hugo-a-study-of-modern-inventive-visual-effects/>.

Shaviro, Steven. Post Cinematic Affect. Washington, DC: Zero, 2010. Print.

—. “The New Cinematography.” The Pinocchio Theory 4 Mar. 2014. Web. 9 May. 2014. <http://www.shaviro.com/Blog/?p=1196>.

Side by Side. Dir. Christopher Kenneally. Tribeca, 2012. Film.

Sobchack, Vivian Carol. Carnal Thoughts: Embodiment and Moving Image Culture. Berkeley: U of California P Berkeley, 2004. Print.

Stork, Matthias. “Video Essay: Chaos Cinema: The Decline and Fall of Action Filmmaking.” Press Play. 22 Aug. 2011. Web.<http://blogs.indiewire.com/pressplay/video_essay_matthias_stork_calls_out_the_chaos_cinema>

Thompson, Kristin. “The Concept of Cinematic Excess.” Film Theory and Criticism: Introductory Readings. Eds. Leo Braudy and Marshall Cohen. Oxford: Oxford UP, 2004. 513-24. Print.

—. “Gravity, Part 1: Two Characters Adrift in an Experimental Film.” David Bordwell’s Website on Cinema 7 Nov. 2013. Web. 25 Feb. 2014. <http://www.davidbordwell.net/blog/2013/11/07/gravity-part-1-two-characters-adrift-in-an-experimental-film/>.

Touch of Evil. Dir. Orson Welles. Perf. Charlton Heston, Janet Leigh, Orson Welles. Universal, 1958. Film.

Udden, James. “Child of the Long Take: Alfonso Cuaron’s Film Aesthetics in the Shadow of Globalization.” Style 43.1 (2009): 26-44. Print.

Žižek, Slavoj. “Children of Men Comments by Slavoj Žižek.” Bonus Features, Children of Men. 2-Disc Special Edition. Universal, 2007. DVD.

Notes

[1] In this article, I attribute a “visual style” (rather than a more traditional “auteurism”) to the collaboration between Cuarón and Lubezki, which of course further incorporates the creative and technical input of several production departments.

[2] It is important to distinguish between several registers of contemporary digital film production in the Cuarón-Lubezki collaboration. I am describing Y Tu Mamá También as a “filmic” film in which the production of the image is primarily a function of film stock production processes: the image is produced exclusively through film stock, post-produced in a manner approximating the editing rationale of film-stock editing, and exhibited on theatre screens through celluloid projection. Conversely, I describe Children of Men and Gravity as “digital films,” to refer to the digital itinerary of the production image. While both Children of Men and Gravity utilize film stock in production, following the critical formulation of David Rodowick, film stock is now always already incorporated within a discretized data field of “digital intermediates and images combining computer synthesis and capture” (164).

[3] Here I draw on Bazin’s formulation of the “sequence-shot” (“plan-séquence”), a long take that captures an entire sequence of action without a cut. For a fascinating reading of the evolution of the term in Bazin’s writing, see Hervé Joubert-Laurencin.

[4] For a provocative discussion of digital cinema’s deceptive long takes, see Rodowick, 163-174. For Rodowick, the digital image, whether shot digitally or digitally composited through computer programs, “is not ‘one’” (166), but a myriad of compositional materials masquerading as an imagistic whole.

[5] For an excellent overview of Bergson’s philosophy of temporal experience, see Guerlac. She offers the following provocative summation of Bergson’s project: “At the turn of the century, Bergson urged us to think time concretely. He invited us to consider the real act of moving, the happening of what happens (ce qui se fait), and asked us to construe movement in terms of qualitative change, not as change that we measure after the fact and map onto space . . . Bergson thinks time as force. This is what he means by duration” (1-2).

[6] Time code refers to Children of Men (DVD, 2-Disc Special Edition). Universal, 2007.

[7] For a comprehensive and compelling account of the function of the digital camera across a range of contemporary films, see Denson et al. Denson suggests that the “unlocatable/irrational camera in [digital films] ‘corresponds’ (for lack of a better word) to the basically non-human ontology of digital image production, processing, and circulation.” In addition, I would also locate this ontology of the digital image in its basic correspondence with a non-material pro-filmic environment.

[8] On first seeing Gravity, I was astonished at what I perceived to be the grossly stereotypical depiction of the Indian-American male, derived in part, I would suggest, from the characterization of Apu in The Simpsons. For a similar reading, see Chitnis.

[9] Time code refers to Gravity 3D Blu-Ray release, Warner Bros., 2014.

Bruce Isaacs is Senior Lecturer in Film Studies at the University of Sydney. He has published work on film history and theory, with a particular interest in the deployment of aesthetic systems in classical and post-classical American cinema. He is the author of the monographs The Orientation of Future Cinema: Technology, Aesthetics, Spectacle (Bloomsbury, 2013) and Toward a New Film Aesthetic (Continuum, 2008), and is co-editor of the special journal issue, The Cinema of Michael Bay: Technology, Transformation, and Spectacle in the ‘Post-Cinematic’ Era (Senses of Cinema, June, 2015). He is currently working on a large-scale project on genre cinema, examining aesthetic points of contact in the work of Sergio Leone, Dario Argento, Brian De Palma and Quentin Tarantino.

Bruce Isaacs, “Reality Effects: The Ideology of the Long Take in the Cinema of Alfonso Cuarón,” in Denson and Leyda (eds), Post-Cinema: Theorizing 21st-Century Film (Falmer: REFRAME Books, 2016). Web. <https://reframe.sussex.ac.uk/post-cinema/4-3-isaacs/>. ISBN 978-0-9931996-2-2 (online)