BY JULIA LEYDA

One of the most striking things about watching the horror movie Paranormal Activity nowadays is the way it portrays the American home just before the housing bubble burst, at the height of what President Bush called “the ownership society.” The film is set in September and October of 2006, the same year it was shot on a shoestring budget by writer, director, cinematographer, and editor Oren Peli, but it only gained wide release in 2009, when it was picked up by Paramount-DreamWorks. That year there were 2.8 million foreclosure filings and unemployment reached 10% in the United States (Adler). Made just before the real estate crash and released two years after, at the height of the credit crisis, the movie centers on a young California couple in their vast new house. Things begin to go wrong for them when, eerily foreshadowing the housing crisis, a demon begins to toy with them, trying to collect on an ancestor’s Faustian bargain. The demon-creditor in Paranormal Activity resonates within the movie’s economic milieu, calling in its debt at the expense of all other concerns; the affective experience of this horror movie aptly foreshadows the credit-crisis ‘structure of feeling’[1] of insecurity, helplessness, and dread in the face of enforced compliance with an economic contract.

To be clear, the Paranormal Activity franchise is not explicitly “about” the neoliberal condition of debtor capitalism; there is no indication that the filmmaker consciously constructed it as an allegory, or, indeed, with any intended message beyond its overt plot about a demon terrorizing a young couple. However, given that the first film was made in the last year of the housing boom, and that its wide release came at the height of the credit crisis, such a cultural interpretation is actually unavoidable—despite film critic Dana Stevens’s self-deprecating comment that her reading of the first film, as a “parable about the credit crisis” that is “all about spiritual and ethical debts coming due,” is “possibly crackpot.” I had the same interpretation of the film before reading her review, and I contend that it is decidedly not crackpot. Indeed, while some films explicitly take on the horrors of the housing crisis—such as Sam Raimi’s Drag Me To Hell, which premiered in early 2009—and the subsequent films in this franchise were made during the crisis, the first Paranormal movie’s housing crisis subtext is largely unintended and all the more telling for that reason.

This chapter reads the Paranormal Activity franchise as an ongoing post-cinematic allegory of debtor capitalism, attending to three levels of analysis and the ways in which they interpenetrate one another. To begin, I examine the ways in which gender, race, and class coalesce within the domestic space of the 21st-century American home. Second, a formal analysis of the movies’ post-cinematic aesthetic calls attention to their cinematography and editing, which both portray and employ digital technologies that have become commonplace in most American homes, as well as crucial in the global circulation of information and capital. The final section looks at the incorporation of immaterial labor in the marketing of the first film in particular, through transmedia paratexts and engagement of horror fans’ social media activity in the cultural production of the Paranormal Activity brand.

Demon Domestic: 21st-Century Horror at Home

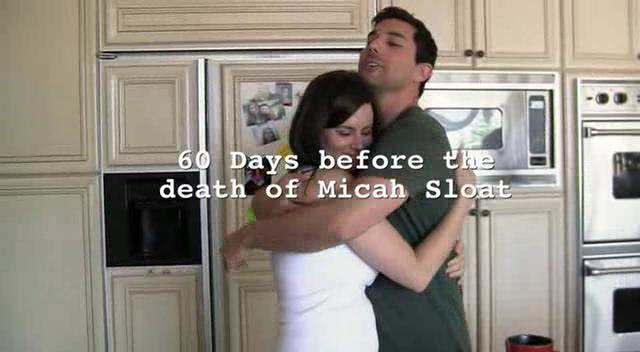

The first movie centers around Katie, an English major, and her partner Micah, a day trader: a young, white, middle-class couple who have just moved into what several reviewers call their “starter home,” implying that it is the first in a series of houses that they will own over the course of their lives (see Solomons). The movie’s action takes place exclusively in this house, producing a claustrophobic effect of isolation and imprisonment, in stark contrast to the idealized notion of the family home as a sign of stability and refuge from the outside world. The movie, shot entirely on Micah’s home video camera (see Figure 1), documents the incidents of daily life and paranormal activity in the house that culminate in the demon-possessed Katie killing Micah.

Paranormal Activity 2 was released one year later in 2010, when the US saw 2.9 million foreclosure filings and 9% unemployment. It, too, is set in a family home in southern California in 2006: this movie tells the story of Katie’s sister Kristi in parallel prequel mode, filling in gaps from the first movie and showing more of what happened beforehand (see Figure 2). In the course of the film, the sisters allude to unusual incidents from their childhood, as Katie tells Kristi about the strange things that have started happening in her new house (viewers who have seen the first film already know how the Katie and Micah situation will turn out). Salient facts also emerge as Kristi’s stepdaughter Ali researches demonology online and deduces that one of Kristi’s ancestors must have made a pact with a demon to deliver the family’s next male child: Kristi’s newborn son, Hunter. This movie, made up of home video and footage from a series of home security cameras, ends with the demon-possessed Katie killing Micah and fleeing their house (as we know from the first movie), then killing Kristi and husband Dan and running away with Hunter. Although I don’t focus on them here, the two subsequent films, Paranormal Activity 3 and Paranormal Activity 4, show the two sisters in their childhood and involve other characters such as their parents and grandmother.

Tim Snelson points out that the last American boom in paranormal movies was during a similar moment of national decline, at the end of the recession- and inflation-plagued 1970s. Back then, anxieties about economic and social upheavals, including feminism and the sexual revolution as well as Watergate and the Vietnam War, fueled a cycle of possession and haunted house films such as The Exorcist (1973) and The Amityville Horror (1979). In the haunted house movies, families experienced hauntings that were place-bound to their homes: ancient burial grounds and gory crimes committed on the site in the past were discovered to be the causes of the paranormal torments those families underwent. These suffering families demonstrate Natasha Zaretsky’s argument that in the crisis-ridden 1970s, “the family served as the symbol for the nation itself,” as “both perpetrator and victim, as the site where the origins of national decline could be discovered and where the damages wrought by it could be assessed” (4). Families in 70s haunted house and possession films underwent agonizing paranormal experiences but, more often than not, survived intact and still together, reinscribing the value of the strong family in times of national crisis.

The Paranormal Activity movies are clearly postfeminist, fitting the representational regime of gender relations that coincided with the economic upturn of the 90s and featured a superficial nod to the gender equality for which 70s feminists fought, while at the same time deemphasizing economic equality, often removing women from the workplace, and centering on heterosexual relationships, domesticity, and consumerism (Negra 4). Made in the context of the housing bubble, the first movie is poignant in its prescience, introducing the fairly traditional young couple in their over-sized, anonymous-looking house surrounded by consumer goods, yet in the second movie, post-crash, we meet an extremely similar young couple in an unnervingly similar, yet even more gender-normative, domestic setting.

Horror movies in the 21st century have shown a marked tendency to appeal to female as well as male spectators. As Pamela Craig and Martin Fradley point out, a hallmark of recent American horror cinema is an “overt courting of a female demographic which both refers back to and updates the proto-feminism of the slasher film’s Final Girl from the late 1970s and early 1980s” (87). Unlike contemporary descendants of the solitary Final Girl figure, the lone female survivor of the conventional slasher horror film whom Carol Clover describes as “boyish” and “virginal” as well as competent and paranoid (204), Katie and Kristi conform to more stereotypically feminine roles: neither works outside the home, both usually defer to their male partners, and neither takes an aggressive role in eliminating the villain. Young adult viewers, whom the movie’s marketing campaign directly targets (more on this below), might find it difficult to sympathize with passive women like Katie and Kristi whose partners disregard their wishes and advice about the demon, positioning them as postfeminist female horror movie leads rather than as more assertive and independent Final Girls. Interestingly, the teenaged girl characters with similar, androgynous names in the second and fourth films, Ali and Alex, take on important Final Girl characteristics even though they are not exactly virginal: they are independent, intelligent, and active, in contrast with the older and more gender-normative Katie and Kristi (see Figure 3).[2]

In their characterization of Katie and Kristi, these movies bear out what Diane Negra and Yvonne Tasker argue: that times of recession are also often times of gender retrenchment, when women’s role in the family home is reinscribed in the face of unemployment and scarcity, as if “equality is a luxury that can no longer be afforded.” In recessionary popular culture, women are more often cast in care-giving roles that emphasize their domestic resourcefulness and protectiveness; Katie and Kristi in the Paranormal Activity movies adopt maternal attitudes toward the men, in contrast to the men’s childish behavior. Indeed, the first three films feature three heterosexual couples in which the women strive in different ways to protect their families within the domestic realm of the home, and in which the men consistently and defiantly behave in ways that endanger them all. Even in the third movie, set in the pre-recession 1980s, Dennis conceals videotaped evidence of the demon from his girlfriend, Katie and Kristi’s mother Julie, because he doesn’t want to frighten her, thus endangering the whole family. Thus, the first two Paranormal movies conform to Tim Snelson’s argument that post-crash domestic horror “expose[s] the inequalities of recession-era households,” while this “centering of housewives and mothers as the only defense against the (re)possession of the American home might ultimately act to reinforce the ideology of female domesticity.” Giving their male partners the upper hand in domestic and economic arrangements allows the men to justify disrespecting the post-feminist characters Katie and Kristi in various ways that lead to more danger.

Katie and Kristi thus manifest the postfeminist tendency toward retreatism, as Diane Negra defines it: women choosing not to work, depending on parents or male partners for economic support, while tending to the family and the running of the household (15). In the 1990s, this retreat to the domestic sphere often figured as a personal choice, as career women opted out of the stressful world of work for the rewards of the home; after the housing crash, women appear more frequently as the stalwart force holding the family together. The first movie is centered around the bedroom, pointing to the centrality of the romantic relationship between Katie and Micah (see Figure 4). Echoing this retreat to the domestic and shifting interest from romance to nurturing, much of the paranormal activity in the second movie occurs in the kitchen and nursery. The demon’s target, stay-at-home mom Kristi, spends most of her time in these two rooms (see Figures 5 and 6). In the earliest scenes, we see the demon behaving as if it knows it is being recorded, spinning the baby’s play-mobile when she steps out and stopping it abruptly just before she returns. The movie’s low-budget domestic horror works powerfully with minimal special effects: one of the biggest “jumps” in the movie occurs as Kristi sits placidly in the kitchen, when suddenly every cupboard door flies open violently at the same moment. The demon assaults the quiet of these otherwise quotidian moments in the most feminine-coded spaces.

The postfeminist qualities of Katie and Kristi appear even more pronounced when contrasted with earlier generations of women in their family. We meet their mother Julie and grandmother Lois in Paranormal Activity 3, which portrays career woman Julie in the late 80s, supporting her boyfriend and daughters Katie and Kristi, much to the disapproval of her domineering mother. Indeed, it was Lois’s demonic entrepreneurship—in making a deal with a demon—that created the condition of indebtedness that dogged her family for generations. In effect, Lois borrowed against a future male descendent, creating a hereditary obligation shouldered unknowingly by her granddaughters when Kristi bears a son.

But the retreatism in Katie and Kristi’s domesticity is still part of the demonic capitalist economy. Kristi’s maternity means that she performs traditional reproductive labor in bearing and caring for her child, though she has opted out of the formal labor market. Even outside of biological motherhood, Katie and Martine, the domestic worker in PA2, also participate in reproductive labor. Katie, although child-free, expresses her desire to be a teacher and shows genuine affection for her baby nephew; she later becomes a kind of foster-mother of demon-children in Paranormal Activity 4. Martine is condescendingly called a “nanny” at the beginning, when in fact she straddles the public/private divide as she performs physical housework in the form of laundry, cooking, and cleaning, as well as affective labor in her mutual emotional bonding with the children as well as waged work for Kristi and Dan’s family (see Figure 7).

In her study of immigrant women’s domestic labor and its representations in popular culture, Mary Romero demonstrates that

[p]urchasing the caretaking and domestic labor of an immigrant woman commodifies reproductive labor and reflects, reinforces, and intensifies social inequalities. . . . Qualities of intensive mothering, such as sentimental value, nurturing and intense emotional involvement, are not lost when caretaking work is shifted to an employee. (Romero 192, citing Silbaugh)

The ironic hierarchies of gender, race, and class in Paranormal Activity 2 crystallize around the figure of Martine, whom Ali sincerely refers to as a part of the family when she learns that her father Dan has fired her. Patriarch Dan exercises his power over Martine when he learns that, despite his instructions, she has continued to burn smudges of dried herbs around their house in her efforts to cleanse the space of the evil spirits she believes abide there.

Yet the figure of the Latina domestic worker, although marginalized in her classed and raced position within the domestic economy, also functions similarly to other female figures such as Katie, Kristi, and Alex: as a source of information about the demon. In his desperation, Dan recalls the fired care worker back to his home to ask for her help; Martine obligingly teaches Dan how to shift the demonic attention from Kristi to Katie, expertise that she appears to have acquired in addition to her domestic skills. Ungrudgingly, Martine offers her advice and assistance to the family that had so recently cast her aside, yet neither she nor Dan realizes that the demon’s ultimate goal is to obtain possession of Hunter regardless of which sister it instrumentalizes to get him; despite successfully switching the demon from Kristi to Katie, the possessed Katie promptly kills Dan in the living room and Kristi in the nursery and absconds with baby Hunter.

Demon Day-to-Day: Ordinary Horror

Descended from the Gothic novel, paranormal horror trains attention on the private home as a domestic site: in which families live, in which power hierarchies co-exist with complex emotional ties, and in which paranormal beings terrorize humans, showing that daily life is both normal and paranormal. Ordinariness gone awry is the mode of many horror movies, and the Paranormal Activity series is no exception. Everything in these movies appears unremarkable, even generic, from the houses themselves—newly built suburban tract homes—to the standard bland furnishings and costumes (see Figures 8 and 9). Nothing stands out as unique, making it easy to imagine that the movie took place in a real home and that it could take place in any home. These lifestyles appear to be typical upper-middle-class, white, and suburban, with plenty of square footage as befits the expansionist American dream of home ownership.

The houses of Katie and Kristi are so similar that they appear interchangeable; moreover, the sisters themselves are also ordinary. For many viewers, their ordinariness led to difficulties in distinguishing Katie from Kristi, particularly when viewing the movies one year apart, as they were released—both have dark hair and are close in age, and they have similar names (see Figure 10). When Kristi’s husband Dan succeeds in displacing the demon’s interest from his wife to her sister Katie, thus explaining in the second film why the events of the first befell Katie, it appears that the sisters are as interchangeable as their houses as far as the demon is concerned. Martine performs domestic work as well, thus demonstrating that one mothering figure can replace another. Baby Hunter is revealed as the demon’s rightful property, according to Lois’s decades-old contract: he becomes the currency with which it can be paid off. So even the baby—the material result of the women’s reproductive labor—is transformed into an object of exchange.

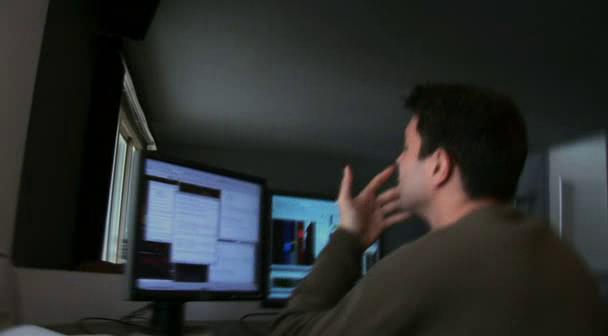

In many ways, too, Micah’s career as a day trader is predicated on domesticity, ordinariness, and exchange. Many reviewers seem to equate “day trader” with “stockbroker.” However, they are not the same: a day trader buys and sells a high volume of stocks from a home computer connected to the Internet, attuned to minimal market movements (see Figure 11). As Randy Martin explains, “day trading came into existence with the 1990s stock market expansion as a function of that confluence between home access to live data on stock price fluctuations and lowered costs per trade” (46). Instead of having to telephone in trade orders, suddenly Internet brokerage account holders could transact—and get rich—with a mouse click, almost by magic. This practice is a key example of the financialization of American life since the 90s, as Martin demonstrates, in that it features the privatization and individualization of a finance-centered livelihood while transposing the risks and anxieties of the market into the domestic space of the home (46). Careers in finance have received scholarly attention in recent decades, often focusing on stockbrokers working for financial services corporations; hypermasculinity accompanies the moral perils of high-risk investing from the first Wall Street film (1987), to the more recent Margin Call (2011), a timespan that the Paranormal series bridges in its four movies (see Negra and Tasker; Annesley and Scheele).

But distinct from these representations of the high finance fraternity in their sleek designer suits, popular images of day trading emphasize the solitary, at-home trader. Micah sports casual clothes, including a t-shirt promoting Coin Net (an online precious metals exchange) (see Figure 12). Instead of competing with colleagues and rivals, day traders are average men who exude “ordinariness” (Martin 49). Micah enjoys spending his money on consumer goods, brandishing a new home video camera that cost him “half of what [he] made” that day. The ordinary-looking lifestyle in the first movie can also be explained in part by the fact that Oren Peli, the filmmaker, used his own new house as its location, including an enormous rear-projection television he bought with the proceeds of his own day trading career in the 90s (Turek).

However, Martin emphasizes the macho albeit solitary egoism of day traders in their compulsion to mask or minimize the (often) massive losses they incur by playing the market so intensively and precariously: “an incessant comparison of success lost” and “hypersensitivity to loss in the eyes of others” characterize the day trader’s persona, whose daily routine is “repeatable until the money runs out, in which each moment is unique and each day is the same” (46). Micah’s obsession with recording the demon on time-stamped videos captured in the bedroom where he and Katie sleep, and around the house as they go about their lives, eerily echoes this repetitive day trader lifestyle in digital form: it takes place in the private space of the home, it foregrounds his prowess with digital technology, and it provides him with a chance to be aggressive and successful (although he merely succeeds in provoking the demon which leads to his death) (see Figure 13).

Indeed, thanks to Micah’s home video camera and the home surveillance cameras in the second film, the movies themselves, and the “real” video footage in them, are instead a digitization of the characters and their bodies, as Steven Shaviro has pointed out—unlike celluloid, there needn’t have been an actual material body before the camera interacting with light to make a physical imprint on a negative, and the images are reduced, literally, to data and digits (Grisham et al.). That abstraction away from materiality is in itself disconcerting; maybe if there were more conventional splatter visuals the movie would feel more grounded, more material. Instead we are left with what Shaviro calls “the low-level dread and basic insecurity that forms the incessant background to our consumer-capitalist lives today,” hours of uneventful video showing Katie and Micah sleeping in fast forward, punctuated by moments of baffling terror that the characters (and often the audience) never fully understand (Grisham et al.) (see Figure 14). Even the alleged safety and security of the mother-child relation appears to be somehow flimsy and insubstantial, like the thin walls of the cheaply made suburban houses that offer no real protection to the families inside from “demonic capital” (Shaviro, in Grisham et al.).

Demon Data: Post-Cinematic Digital Aesthetics

These horror movies foster affective responses appropriate to the recession-strapped 21st century, an era that few will deny is post-cinematic. Shaviro argues that “[d]igital technologies, together with neoliberal economic relations, have given birth to radically new ways of manufacturing and articulating lived experience” (2). As that definition suggests, post-cinematic media “generate subjectivity and . . . play a crucial role in the valorization of capital,” just as they draw our attention to the parallel uses of technology in entertainment and finance: “the editing methods and formal devices of digital video and film belong directly to the computing-and-information-technology infrastructure of neoliberal finance” (Shaviro 3; reprinted in this volume). Here in their form and in the movies’ diegesis, the digital is the link between the nightmare of debtor capitalism and the horror of the camera as non-human agent that captures the malevolent actions of the non-human demon. The Paranormal Activity films, as I have shown, exemplify postfeminist recessionary texts in their representations of gender and the domestic; they are also post-cinematic in their interest in the themes and technologies as well as the structures of feeling of the digital age. Caetlin Benson-Allott places the Paranormal Activity films within the recent trend in what she names “faux footage films” that call attention to the plethora of now ordinary video technologies in the American home, which are increasingly figured as malevolent (186).

The video cameras in the movies digitize their human subjects, thus turning something we might call private reality into data. Extending and elaborating on the handheld digital aesthetics of The Blair Witch Project (1999), the first two Paranormal films also “reveal the extent to which the amateur, unpolished technique of faux footage horror represents the psychic boundary between public and private” by allowing access to what are presented to us as rough unedited footage, home movies, and private surveillance videos (Benson-Allott 182). The domestic digital aesthetics of the Paranormal Activity franchise are integral to the troubling of the public-private boundary that Benson-Allott indicates; the home-made and faux footage only escalates the horror in these movies as it depicts the penetration of invisible, financialized demon capital into the refuge of the family home.

The faux footage horror movies, including the Paranormal Activity films, are also “weapons in a format war being fought by copyright holders and pirates over our e-spectatorship” at a time when, thanks to the possibility for rapid digital data transmission via the internet, piracy has become a major concern of the entertainment industry, as Benson-Allott argues (171). The cycle of faux footage horror at the beginning of this century instills in audiences a sense of fear and anxiety about the “repercussions for watching the wrong video or watching the wrong way,” and thus contributes to the spirit of industry anti-piracy campaigns that threaten viewers with legal action (Benson-Allott 183). In Paranormal Activity, breaking the rules also carries strong punishments. We learn that the demon gets stronger and more aggressive as Micah records it on video and watches the footage, ignoring Katie’s warnings. He childishly continues to break her “rules,” smirking to the camera when he promises he won’t “buy a Ouija board,” fully intending to borrow one; his mockery of her directives parallels the defiance inherent in piracy, although obviously with more severe penalties (see Figure 15). Beyond their context within the copyright wars, however, the Paranormal films also underscore the dire consequences of defying the rules of debtor capitalism in the digital age.

The Faustian contract that Katie and Kristi’s grandmother made with the demon becomes the engine of deadly destruction as the demon takes possession of what is owed. Whatever benefits Lois gained in the past by making this contract, her granddaughters now must pay the balance due: Kristi’s son, Hunter. The movies thus dramatize in hyperbolic horror-movie style the condition of indebtedness that Maurizio Lazzarato argues “represents the very heart of neoliberal strategy, [and] now occupies the totality of public space” (38). Released during the foreclosure crisis in 2009, Paranormal Activity portrays the horror of a debt that cannot be evaded or expunged, which can lead to the repossession of a cherished object such as the family home, or in this case, a child. Through her reproductive labor and assisted by Martine and Katie, Kristi must assume the debt of her grandmother Lois, and pay the demon-creditor what is owed.

The hereditary nature of this particular debt also plays on the growing sense of resentment among white, middle-class Americans who are realizing that younger generations will not have access to the same advantages and opportunities as their antecedents—as the debt economy engulfs ever-increasing percentages of personal income, a record low 14% of Americans believe that today’s children will do better than their parents (“New Low”). While at least the belief in upward mobility has long been taken for granted in American life, now it is mainly capital that moves, and most often it is leaving. As Randy Martin points out, financialization has ushered in changes in American structures of feeling around the home itself: whereas owning property used to be a sign of stability for previous generations, it is now a potential vulnerability, and in fact, “[w]hat was once a source of security is now a source of risk” (Martin 31). The Paranormal Activity movies allegorize the way in which possession and re-possession have become horrific concepts in the 21st century.

The mobility and invisibility of the demon, its ability to navigate the home unseen and to inhabit the body through possession, echoes the insidious, digitized mobility of transnational finance capital, which has forced so many homeowners into foreclosure and repossession. Just as the demon demands payment of an ancestor’s debt, the predatory mortgage, abstracted beyond verifiable recognition into digitally traded securities, allows an outsider to take away one’s very home and hearth. Moreover, the digitization, agility, and decentering of financial systems and instruments make them harder to see or resist; the Paranormal Activity movies portray the demon as an elusive, disembodied, yet personalized evil entity. Demonic possession—as well as the transfer of the demon’s possessive attention from Kristi to Katie—recalls the contemporary phenomenon of identity theft, which can have serious repercussions: you can lose everything, not to mention your damaged credit rating. These digital forms of theft are only possible in an increasingly data-driven, disembodied, financialized world. The non-human demon, like a bad credit rating or identity theft, trails the sisters throughout their lives until one of them bears a son, which makes it more frightening than a site-specific haunting, in that moving away will not allow them to escape the hostile, disembodied demonic force.

The absence of an embodied evil in the movies invests the video cameras with sinister overtones, raising the complex question of point of view. In this way, too, the movies repurpose the horror convention of de-familiarizing the home as haven to make it a site of terror and the uncanny. Digital imaging technologies—home video, surveillance, and security cameras, in particular—are ubiquitous, ordinary artifacts of contemporary American life. Indeed, security cameras exist in order to make us feel safer, yet reviewing the interminable, repetitive videos produces more anxiety for us and the characters by revealing what a character can never see firsthand: herself sleeping and what goes on while she sleeps. Watching the speeded-up videos of Katie and Micah sleeping as lights switch on and off, the door moves closed and open again, and the sheet billows up around their bodies, the footage emphasizes their unconsciousness and vulnerability (see again Figure 14, above). Moreover, while a sleeper can never see herself from outside, the demon, like the camera, can; it can also move her around, inhabit her body, and then look out from within her body. However, unlike conventional horror cinema’s use of point of view to increase suspense, such as filming a sequence from the killer’s perspective observing the unsuspecting victim, this camera does not represent any human point of view. Positioning the camera in a non-human POV, the movie produces an uncanny sense of helplessness; we occupy neither the demon’s perspective nor the sleeping characters’, but that of a machine, the diegetic digital camera.

In the Paranormal movies, the digital modes of production condition the kinds of affect the movie generates: their cinematography and editing corral us into certain perceptive modes. The omniscience of the “unmanned” cameras, however, begins to resemble a form of mastery over the humans—the cameras are superior, all-seeing witnesses, and force people—characters and spectators alike—to watch helplessly. An almost sadistic tone emanates from this kind of enforced and hobbled surveillance. Unlike other kinds of horror that emphasize the excessive wounding of the flesh, bodies are not mutilated or tortured in these movies; all of the Paranormal Activity movies are surprisingly free from gore and protracted violence. Yet they still fit the classification of body genres, as Linda Williams defines them: “trashy” movies of the horror, melodrama, or pornography genres that provoke strong physical responses from the audience (4). There are plenty of “jumps”—involuntary physical expressions of fear and surprise in the Paranormal series, but the movie also controls the viewer’s body in other ways. For example, the camera fixed on its tripod in Paranormal Activity and the static security cameras in each room in Paranormal Activity 2 force the spectator to scan the frame continuously, because the fixed camera cannot highlight action or details using close-ups or editing, as in classical cinema (see Figures 16 and 17). Calling attention to the film’s form in a way that makes viewers more anxious and uncomfortable, this camera work produces a form of digital dramatic irony. That is, when recording while humans are sleeping, absent, or looking the other way, the always-on cameras “know” and “see” more than the characters, and thereby we viewers do as well, as long as we assiduously do the extra work and pick out by our own effort what is important in the frame. In the next section, I examine some of the other kinds of extra work the Paranormal movies assign to their viewers.

Demon Branding: Immaterial Fan Labor and Blurred Boundaries

Paramount-DreamWorks has built the Paranormal Activity franchise from an ultra-low-budget production into a blockbuster series; the films thematize and exemplify the extent of digital technology’s permeation into contemporary US life not only in their story and cinematic form, but also in their marketing and branding. Picking up the rights to the first Paranormal Activity movie, which Peli made for $15,000, the studio reportedly paid $350,000; subsequently, the movie has grossed over $193 million worldwide (“Paranormal Activity”). Despite debate over whether to include marketing costs ($10 million) when calculating return on investment, the first Paranormal Activity movie is widely considered the most profitable movie ever made, and subsequent movies in the franchise have set other records (O’Carroll). But still uncounted is the added value of the fan labor as a significant component in the marketing of the movie. The specifically 21st-century variety of dynamic online fan participation serves as a contrast—and perhaps an antidote—to the affective register of the movie, consisting of helplessness, fear, and anxiety. Just as the movies’ post-cinematic aesthetics enact a peculiar form of bodily control over viewers—making us actively search within the frame to locate suspicious movement, the movie’s branding entails a variety of viewer activities in addition to simply buying access to the film (in the form of a cinema ticket, DVD purchase or rental, or streaming event).

One of the reasons the franchise became so successful may be that it resembles the young horror movie fan’s social media communications: the public, performative online behaviors that we practice every day on Twitter and Facebook, sharing shaky homemade video and private domestic scenes with our so-called “friends.” The new media publicity campaign for the first film, under producer Jason Blum and spear-headed by the PR company Eventful, encouraged fans to click a button on the movie’s website to “Demand It!” promising that those towns with the most clicks would get the movie’s release sooner. Thus the executives could see the buzz around Paranormal Activity grow day by day and were able to pinpoint specific locales where it was attracting more attention. Eoin O’Carroll points out that just urging “the small, initial commitment of clicking on a button makes that person more likely to follow through and go see the film.” But the other reason the “Demand It!” marketing campaign was (and continues to be) so successful is the way it drafts the fans into unpaid labor as marketers themselves, targeting viewers like themselves. This campaign exemplifies what Sarah Banet-Weiser argues is a hallmark of the new “brand culture” of the 21st century, in which

[c]onsumers contribute specific forms of production via voting, making videos for the campaign, workshopping, and so forth, but the forms of their labor are generally not recognized as labor (e.g., participating in media production, DIY practices, consumer-generated content). (42; see also Hamilton and Heflin; Jarrett)

As the fans went to the website and clicked the “Demand It!” button, they reinforced their own consumerist desire for the movie, and at the same time demonstrated it publicly for both the movie studio and the rest of the movie’s fan base to see, thus contributing to the production of publicity and the market research for the movie.

Blum explains using a domestic metaphor: “You bring it home to yourself, instead of feeling that it’s being pushed on you” (qtd. in Cieply). By taking an active role in demanding the movie, and taking part in the movie’s PR activities on Facebook, Twitter, and other social media platforms, fans build “a kind of affective, authentic engagement into the product itself,” participating in the branding campaign instead of just being addressed by it (Banet-Weiser 38). This form of immaterial labor—which binds the consumer to the product through monetized, unpaid online activity—also blurs the boundaries between consumers and producers, employing “the emotive relationships we all have with material things, with products, with content, and seeking to build culture around those brands” (Banet-Weiser 42; 45). The studio expected it would take weeks to attain one million “Demand It!” clicks, but the fervent online horror fans did it in four days (Evangelista). A similarly active marketing role for fans worked through the Twitter campaign using the official Paranormal Activity account, @TweetYourScream, to encourage fans to post their reactions.[3]

Indeed, given the widespread practice of piracy among the movie’s young target audience, the extraction of immaterial labor online—through Demand It!, Twitter, and other social media platforms—serves as a form of payment in addition to, or in lieu of, the legitimate price of the commodity, which many of them avoid by viewing it illicitly. The movie corporations thus profit not from their ownership of copyright, which they still hotly defend in the current battles over intellectual property laws, but they also accumulate capital in the form of voluntary, even enthusiastic, online immaterial labor. That is, they benefit from the online activity of others just as Google’s Page Rank algorithm does according to Matteo Pasquinelli: “Google is clearly a supporter of the free content produced by the free labor of the free multitudes of the internet: it needs that content for its voracious indexing” (original emphasis).[4] The immaterial labor of online Paranormal Activity fans and would-be fans, then, constitutes a kind of hedge bet against the alleged losses to piracy that the industry decries in the war on piracy.

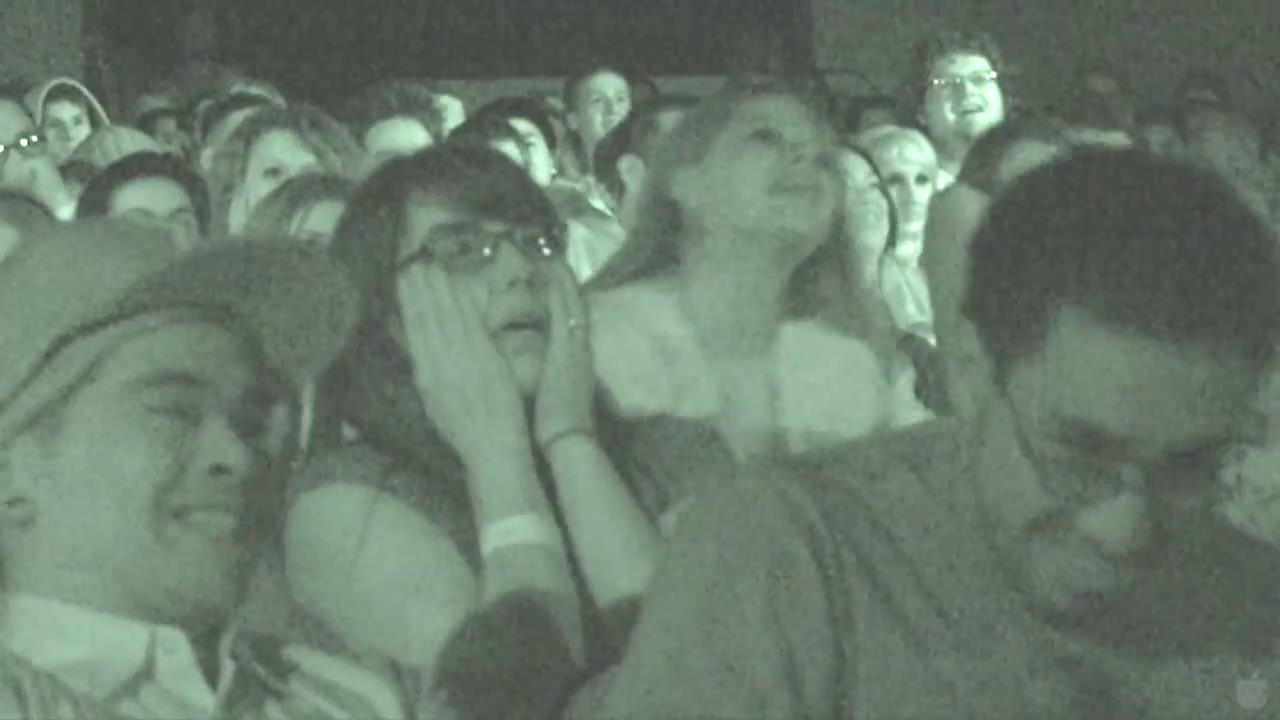

The first Paranormal Activity movie’s trailers were also innovative in their active incorporation of audiences and digital technology into the publicity campaign. The ads mimic the film’s low-budget visual aesthetic, with descriptive title cards setting the stage at a test screening in Hollywood, presenting both the movie and the trailer “as historical events” (Benson-Allott 170). The trailers dramatize the experience of the audience, along with the characters in the film, producing a parallel narrative about one of the first groups to “experience” the movie (see Figure 18). Then the lights go down, the night-vision camera engages, and we see the darkened theater, filled with spectators and shot from the back with a view of the screen, as well as from down in front, where we can see their faces reacting in horror as they watch the movie: mouths open, eyes covered, jumping involuntarily, screaming out loud. As Benson-Allott points out, through its use of similar technology to shoot the audience footage, “the ad’s night-vision scenes ostensibly document real reactions, just as Peli’s movie ostensibly documents real demonic possession,” thus blurring the distinctions between the real theater audience and the fictional characters in the movie (188). By encouraging viewers of the trailer to place themselves in the position of the terrified viewers of the movie in that test screening, the trailer also reinscribes the ordinariness that pervades the movie, as viewers see regular people in the trailer consuming the movie, which is purportedly about regular people (see Figure 19 and 20).

The trailer also blurs the boundary between the product being sold (the movie) and the target buyers (the audience), as it places “viewers” both within the trailer and in the position of watching the trailer. The pro-filmic objects of the trailer are “viewers” like you, watching the movie, just as the characters in the movie are “really” Katie and Kristi. The Paranormal Activity trailer, as an artifact of brand culture, demonstrates the way in which the “separation between the authentic self and the commodity self not only is more blurred, but this blurring is more expected and tolerated”—and, I would add, enjoyed (Banet-Weiser 13, original emphasis).

Conclusion

Paranormal Activity and Paranormal Activity 2 trace a family’s troubled history with a demon across several generations, but always located within a family home and centered around a female character. The demon in the first two Paranormal films has come to claim a debt resulting from a contract with an ancestor, who has in a sense “mortgaged” future male offspring in exchange for power and wealth. Given the series’ immediate context within the credit crisis and the Great Recession, we can interpret the demon as an allegory for debt under neoliberal capitalism: it is just as invisible, inescapable, and imperfectly apprehended via digital media. Like the video data that constitutes the “film” itself, and like the transnational finance capital and the intangible systems of consumer credit that permeate contemporary life, the demon is unseen and immaterial, yet it exercises enormous power.

Works Cited

Adler, Lynn. “US 2009 Foreclosures Shatter Record Despite Aid.” Reuters 14 Jan. 2010. Web. 15 Oct. 2013. <http://uk.reuters.com/article/us-usa-housing-foreclosures-idUSTRE60D0LZ20100114>.

Annesley, Claire, and Alexandra Scheele. “Gender, Capitalism, and Economic Crisis: Impact and Responses.” Journal of Contemporary European Studies 19.3 (2011): 335-47. Print.

Banet-Weiser, Sarah. Authentic™: The Politics of Ambivalence in a Brand Culture. New York: New York UP, 2012. Print.

Benson-Allott, Caetlin. Killer Tapes and Shattered Screens: Video Spectatorship from VHS to File Sharing. Berkeley: U of California P, 2013. Print.

Cohn, D’Vera. “Middle-Class Economics and Middle-Class Attitudes.” Pew Social Trends. 22 Aug. 2012. Web. 15 Oct. 2013.

Cieply, Michael. “Thriller on Tour Lets Fans Decide Next Stop.” New York Times 20 Sept. 2009. Web. 9 Oct. 2013.

Clover, Carol. “Her Body, Himself: Gender in the Slasher Film.” Misogyny, Misandry, and Misanthropy. Ed. R. Howard Bloch and Frances Ferguson. Berkeley: U of California P, 1989. E-book.

Craig, Pamela, and Martin Fradley. “Teenage Traumata: Youth, Affective Politics, and the Contemporary Horror Film.” Hantke American 77-102.

Evangelista, Benny. “How Net Activity Boosted Paranormal Activity.” San Francisco Chronicle 16 Oct. 2009. Web. 10 Oct. 2013. <http://www.sfgate.com/business/article/How-Net-activity-boosted-Paranormal-Activity-3213274.php>.

Grisham, Therese, Julia Leyda, Nicholas Rombes, and Steven Shaviro. “Roundtable Discussion on the Post-Cinematic in Paranormal Activity and Paranormal Activity 2.” La Furia Umana 11 (2011). Web. Reprinted in this volume.

Hamilton, James F., and Kristen Heflin. “User Production Reconsidered: From Convergence to Autonomia and Cultural Materialism.” New Media and Society 13.7 (2011): 1050-66. Web. 18 Oct. 2013. <http://nms.sagepub.com/content/early/2011/03/30/1461444810393908>.

Hantke, Steffen. “Introduction: They Don’t Make ‘Em Like They Used To: On the Rhetoric of Crisis and the Current State of American Horror Cinema.” Hantke American vii-xxxii.

—, ed. American Horror Film: The Genre at the Turn of the Millennium. Jackson: U of Mississippi P, 2013. Print.

Jarrett, Kylie. “The Relevance of ‘Women’s Work’: Social Reproduction and Immaterial Labor in Digital Media.” Television and New Media 15.1 (2014): 14-29. Web. 15 Jan. 2014. <http://tvn.sagepub.com/content/early/2013/05/13/1527476413487607.abstract>.

Lazzarato, Maurizio. The Making of the Indebted Man. Trans. Joshua David Jordan. Amsterdam: Semiotext(e), 2011. Print.

Martin, Randy. The Financialization of Daily Life. Philadelphia: Temple UP, 2002. Print.

Negra, Diane. What a Girl Wants? Fantasizing the Reclamation of Self in Postfeminism. New York: Routledge, 2008. Print.

Negra, Diane, and Yvonne Tasker. “Introduction: Gender and Recessionary Culture.” Gendering the Recession. Ed. Diane Negra and Yvonne Tasker. Durham: Duke UP, 2014. Ebook.

—. “Neoliberal Frames and Genres of Inequality: Recession-Era Chick Flicks and Male-Centered Corporate Melodrama.” European Journal of Cultural Studies 16.3 (2013): 344-61. Web. 31 Aug. 2013.

“New Low: Just 14% Think Today’s Children Will Be Better Off Than Their Parents.” Rasmussen Reports. 29 Jul. 2012. Web. 15 Oct. 2013. <http://www.rasmussenreports.com/public_content/business/jobs_employment/july_2012/new_low_just_14_think_today_s_children_will_be_better_off_than_their_parents>.

Newman, Michael Z., and Elana Levine. Legitimating Television: Media Convergence and Social Status. New York: Routledge, 2012. Print.

O’Carroll, Eoin. “How Paranormal Activity Became the Most Profitable Movie Ever.” Christian Science Monitor. 30 Oct. 2009. Web. 9 Oct. 2013. <http://www.csmonitor.com/Technology/Horizons/2009/1030/how-paranormal-activity-became-the-most-profitable-movie-ever>.

“Paranormal Activity.” Box Office Mojo. Web. 9 Oct. 2013.

Pasquinelli, Matteo. “Google’s PageRank Algorithm: A Diagram of Cognitive Capitalism and the Rentier of the Common Intellect.” Deep Search: The Politics of Search Beyond Google. Ed. Konrad Becker and Felix Stalder. London: Transaction, 2009. Web. 11 Jan. 2014. <http://matteopasquinelli.com/google-pagerank-algorithm/>.

Romero, Mary. “Nanny Diaries and Other Stories: Immigrant Women’s Labor in the Social Reproduction of American Families.” Revista de Estudios Sociales 45 (2013): 186-97. Web. 8 Jan. 2014. <http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=81525692018>.

Schwartz, Herman. Subprime Nation: American Power, Global Capital, and the Housing Bubble. Ithaca: Cornell UP, 2009. Print.

Shaviro, Steven. Post-Cinematic Affect. Winchester: Zero, 2010. Print. (Introduction reprinted in this volume).

Snelson, Tim. “The (Re)possession of the American Home: Negative Equity Gender Inequality, and the Housing Crisis Horror Story.” Gendering the Recession. Ed. Diane Negra and Yvonne Tasker. Durham: Duke UP, 2014. Ebook.

Solomons, Jason. Rev. of Paranormal Activity. Guardian, Guardian Media Group. 29 Nov. 2009. Web. 4 Nov. 2013. <http://www.theguardian.com/film/2009/nov/29/paranormal-activity-review>.

Stevens, Dana. “Paranormal Activity: A Parable about the Credit Crisis and Unthinking Consumerism.” Slate.com 30 Oct. 2009. Web. 6 Jan. 2014. <http://www.slate.com/articles/arts/movies/2009/10/paranormal_activity.html>.

Turek, Ryan. “Exclusive Interview: Oren Peli.” Shock Till You Drop. 9 Mar. 2009. Web. 4 Oct. 2013. <http://www.shocktillyoudrop.com/news/5123-exclusive-interview-oren-peli/>.

Vancheri, Barbara. “Making of Paranormal Activity Inspired by Filmmaker’s Move to San Diego.” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette 19 Oct. 2009. Web. 4 Oct. 2013. <http://www.post-gazette.com/ae/movies/2009/10/19/Making-of-Paranormal-inspired-by-filmmaker-s-move-to-San-Diego/stories/200910190154>.

Williams, Linda. “Film Bodies: Gender, Genre, and Excess.” Cinema Journal 44.4 (1991): 2-13. Print.

Zaretsky, Natasha. No Direction Home: The American Family and the Fear of National Decline, 1968-1980. Chapel Hill: U of North Carolina P, 2007. Print.

Notes

Parts of my argument in this chapter first emerged in an online round-table published in La Furia Umana in 2011 in which Nicholas Rombes, Steven Shaviro, and I responded to one another and to thoughtful prompts from Therese Grisham, so I owe all three a debt of gratitude for such a rich and cooperative discussion in which I could test and develop my fledgling ideas about these films. The enthusiastic discussions that ensued after I presented drafts in lecture form at Edinburgh Napier University and Leibniz University of Hannover further contributed to the development of this chapter. Thanks are also due to Sarah Artt, Caetlin Benson-Allott, Shane Denson, Sarah Goodrum, Diane Negra, Anne Schwan, Christopher Shore, and Tim Snelson for feedback and comments at various stages of development. This version is a reprint of the article published in Jump Cut 56 (2014).

[1] Raymond Williams coined this expression to describe emotions and perceptions common to a specific time and place and expressed in contemporaneous arts and other cultural forms. Steven Shaviro draws on this concept from Williams in his definition of post-cinematic affect (reprinted in this volume).

[2] Thanks to Caetlin Benson-Allott for pointing this out.

[3] This Twitter account, like the franchise’s official Facebook page, is still active and is now publicizing Paranormal Activity: The Ghost Dimension and upcoming productions, with over 101,000 followers. The original official website <www.paranormalmovie.com> also still exists and publicizes the latest release, although it currently doesn’t allow IP addresses outside the US to view the site.

[4] Thanks to Shane Denson for pointing me to Pasquinelli here.

Julia Leyda is Senior Fellow in the Institute for Advanced Sustainability Studies, Potsdam, as well as Fellow with the DFG Research Unit “Popular Seriality–Aesthetics and Practice” and Senior Research Fellow in the Graduate School for North American Studies, both at the John F. Kennedy Institute, Freie Universität Berlin. In August 2016, she will take up an Associate Professorship of Film Studies in the Department of Art and Media Studies at the Norwegian University of Science and Technology in Trondheim. She is editor or co-editor of Todd Haynes: Interviews (UP of Mississippi, 2014), Extreme Weather and Global Media (with Diane Negra, Routledge, 2015), and The Aesthetics and Affects of Cuteness (with Joshua Paul Dale, Joyce Goggin, Anthony P. McIntyre, and Diane Negra, Routledge 2017). She is author of American Mobilities: Class, Race, and Gender in US Culture (Transcript, 2016), and is working on two new books: Home Economics: The Financialization of Domestic Space in 21st-Century US Screen Culture and Cultural Affordances of Cli-Fi: 21st-Century Scenarios of Climate Futures.

Julia Leyda, “Demon Debt: Paranormal Activity as Recessionary Post-Cinematic Allegory,” in Denson and Leyda (eds), Post-Cinema: Theorizing 21st-Century Film (Falmer: REFRAME Books, 2016). Web. <https://reframe.sussex.ac.uk/post-cinema/4-1-julia-leyda/>. ISBN 978-0-9931996-2-2 (online)