BY CAETLIN BENSON-ALLOTT

What the majority of spectators seem to want and value from animation is not a gloss on “metaphysical effort” but rather . . . “metaphysical release.”

—Vivian Sobchack, “Final Fantasies”

Be careful what you wish for.

—Coraline

Before Avatar (James Cameron, 2009) grossed $2.7 billion in worldwide ticket sales, Henry Selick’s Coraline (2009) was widely hailed as the best 3-D movie ever made (“Avatar”). By offering uncanny adventure “for brave children of all ages,” Coraline bestowed digital stereoscopic filmmaking with artistic and cultural prestige, affirming exhibitors’ and cinemagoers’ growing interest in digital projection.

Film distributors were already sold; for the previous eleven years, they had pressured exhibitors to adopt a digital delivery and projection system and abandon expensive celluloid prints. They also wanted exhibitors to pay for this technological overhaul even though the theater-owners did not foresee any recompense in replacing their existing celluloid projectors with digital substitutes. RealD gave theater-owners a reason to convert when early experiments in polarized stereoscopic image projection, including Chicken Little 3D (Mark Dindal, 2005) and Beowulf 3D (Robert Zemeckis, 2007), demonstrated that more viewers would come out—and pay more per ticket—to see movies in digital 3-D.[1] Subsequently Coraline, Up (Pete Docter and Bob Peterson, 2009), Avatar, and Alice in Wonderland (Tim Burton, 2010) launched a genre of high-profile, high-concept digital 3-D movies and confirmed that RealD projection can be exceedingly profitable for all involved.

Ironically, the spectatorial pleasures of digital 3-D cinema are nowhere near as clear as the profits, although scholars have now begun to explore what value this third dimension adds to the spectatorial experience (see Elsaesser; Higgins). Previous incarnations of 3-D cinema—such as the red-and-cyan anaglyph system of the 1950s or the (analog) polarized Stereovision of the early 1980s—came and went quickly and without lasting industrial or aesthetic impact, but RealD proved much more popular with viewers, popular enough that major studios (specifically Dreamworks Animation SKG) converted to entirely 3-D production. In 2010, Samsung introduced consumer-grade 3-D HDTV sets to capitalize on the success of digital 3-D cinema. Thus it is time investigate what sort of desire digital 3-D produces and satisfies in its spectator and how it integrates itself into Western systems of representation. To paraphrase Vivian Sobchack’s earlier work on 2-D digital animation, we need to ask what we want from RealD and what RealD wants from us: what new dimension is it opening up (Sobchack 172)? Henry Selick’s Coraline occasions related questions about desire, space, and embodiment through its representation of a young girl opening the door onto an Otherworld concealed within her own. Unlike previous RealD features, Coraline harnesses the uncanniness of stereoscopic animation and uses it to acknowledge and produce a locus for the digital uncanny.[2] It manipulates biocular vision—the human physiology that enables depth perception and thus “3-D imagery” or stereoscopy—to offer viewers a new receptacle of uncanniness for digital mimesis, namely, the 3-D image’s virtual depth of field. By exploiting biocular vision as binocular vision, the movie returns our visual perception to us as mediated spectacle and as uncanny in the Freudian sense. In both its optics and its metaphysical tropes, Selick’s movie suggests that RealD is “nothing new or alien, but something which is familiar and old-established in the mind and which has become alienated from it” (Freud, “Uncanny” 363-64). In short, Coraline promotes the uncanniness of the digital image to give its spectator a new experience of—one might even say a new standard for—visual verisimilitude to replace indexical realism now that the latter has been rendered obsolete by digital image capture, distribution, and exhibition.

Coraline’s narrative also provides context for these metacinematic reflections by narratively and figurally taking up an ongoing debate about the relationship between form, matter, and femininity. Both the film’s title and its representation of the new dimensionality of the image cite Plato’s chora, the receptacle “at the very foundations of the concept of spatiality” (Grosz 9). Its story thus invokes recent debates among Jacques Derrida, Julia Kristeva, Luce Irigaray, Elizabeth Grosz, and others about the chora’s significance as a metaphysical figure—an unintelligible space that gives form to matter—and a trope within traditional patriarchal theories of representation. Grosz also suggests that the chora “contains an irreducible, yet often overlooked connection with the functions of femininity” (24), which emerges in Coraline as the Beldam, a wicked witch who lives outside yet supports the materialist and gender-normative fantasies of Coraline’s world. Through the Beldam, Coraline gives the chora a voice and a character, one who wants to imagine herself as an Other Mother and her house as a nurturing receptacle outside the ever-changing world, but who is ultimately undone by her desire to incorporate as well as produce. As the maternal threat of jouissance, the Beldam provides Coraline with an occasion to perform material excess and a means to represent both the allure and the horror of virtual worlds.[3]

The virtual depths associated with the Beldam render the digital 3-D image visible as a dematerialized inscriptional space in which relationships between Form and Matter, ideal and embodiment, can be worked out. To that end, the gendered terms of Coraline’s narrative invite the spectator to reconsider the patriarchal dynamics behind Western metaphysics of representation. By focusing on Coraline’s depiction of the Beldam and the formation of her character, I suggest that the movie uses its chora to produce a post-cinematic “bridge between the intelligible and the sensible, mind and body” that can replace celluloid’s indexical invocation of the material while also providing catharsis for that loss (Grosz 112). The movie realizes these tensions through its digital approach to stop-motion animation, which enables it to contemplate figurally the transition into and out of materiality. Coraline’s stop-motion technology blends computer-designed profilmic models and computer-generated imagery (CGI) to place the uncanny frisson of stop-motion in conversation with the uncanny surplus of digital 3-D projection. Thus as it shifts between digital and analog image production, the movie invites its spectator to meditate on the psychic dynamics of dimensionality—not to mention the gendered dynamics of materiality. As Sianne Ngai has argued, the inherent instability of stop-motion produces a tendency towards excessive movement, an excessive animatedness that she links to long-standing racist stereotypes (89-125). For the spectator, stop-motion resembles an apparatus always on the verge of escaping, running amok, subverting the social hierarchies of the bodies and matter it is asked to produce. Coraline builds on the racialized overtones of excessive animation and the uncontrollable animatedness of its stop-motion to capture the instability of matter and image, as well as the inherent uncanniness of the body, and offer them back to the spectator as the post-cinematic experience.

* * *

Technically, any film not computer-animated or illustrated by hand could be described as stop-motion; at its most basic level, “stop-motion animation” describes any filmic record of a physical, profilmic model that moves or is moved between frames. The earliest surviving stop-motion movie dates from 1902 and revels in the expressive potential of material manipulation. In “Fun in a Bakery Shop” (Edwin S. Porter), a baker smothers an intruding rat with a lump of dough and then delights in molding the latter into a series of facial likenesses. Subsequent animators advanced this technique with puppets and model animation, which uses internally-framed dolls to create the illusion of motion. Because model animation requires extremely exacting adjustments between shots, 1940s stop-motion artists turned to swapping out different modular components of a doll between shots, also known as replacement animation, and their 1970s counterparts tried Claymation, which uses wire skeletons coated in plasticine to increase pliability. Although replacement animation first entered Hollywood through George Pal’s Puppetoons in 1940, it did not yield a full feature until Henry Selick’s The Nightmare Before Christmas (1993). Selick continued to explore replacement animation in James and the Giant Peach (1996) and Monkeybone (2001) before turning briefly to computer animation for Coraline’s predecessor, Moon Girl (2005). In this digital short, a young boy travels to the moon, meets its current protectress, and helps her defeat the evil ghosts who would darken it. Moon Girl anticipates Coraline’s interest in the relationship of (outer) space to image production, and it also marks an important evolution in Selick’s approach to animation. Before RealD brought stereoscopy into the twenty-first century, computer animation was widely marketed as “3-D animation” because it employs virtual 3-D models to produce its 2-D graphics. Selick’s brief foray into computer animation for Moongirl thus suggests an aesthetic preparation for Coraline’s subsequent experiments with perspective. As animation legend Ray Harryhausen recently observed, “many of the techniques used in stop-motion animation are part of the process in preparing CGI work” (qtd. in Wells 97), and both Moongirl and Coraline invite the spectator to reflect on the fluidity between matter and image, modeling and 3-D image production, that defines the latter film.

Indeed, Selick’s 2009 stop-motion feature is visually distinct from yet shares many production techniques with the other computer-animated features released that year. Most computer-animated films use virtual models designed through mathematical (usually Cartesian) coordinate systems to make two-dimensional images look three-dimensional. These virtual models are often based on artists’ three-dimensional sculptures, and in that sense, CGI animation captured the designation “3-D animation” because it looked like stop-motion animation (or at least more like it than cel animation ever could) while offering the smooth transitions and impossible effects typically associated with cel animation. Today, stop-motion is able to mimic computer-animation’s smoothness and surrealism by (re)materializing digital models. 3-D printers, colloquially known as “fabbers,” enabled Selick and Laika Studios to manufacture quickly the thousands of modular components needed to animate a feature-length stop-motion film. Without digital models and 3-D printing, Laika could never have produced the 15,300 faces necessary for Coraline’s twenty-one characters to replicate human speech and expressions.

Thus Coraline’s blend of computer-designed stop-motion puppetry and computer-aided special effects returns three-dimensional animation to its historic medium while also bringing the latter into the future of three-dimensional film: RealD. RealD is the most popular format for digitally projecting stereoscopic images, and although it has competitors, such as Dolby 3D and MasterImage 3D, it controlled 85% of US theatrical 3-D exhibition as of 2011 (Bond). Most of its perceived competitors are actually licensed corporate partners—e.g., Disney Digital 3D—or are not actually digital, such as the original IMAX 3D system. RealD uses a liquid crystal adapter attached to a digital projector to polarize 144 frames per second in opposite directions, half clockwise and half counterclockwise (see Cowan). For a viewer wearing RealD’s polarized glasses, each eye picks up only every other image, while the distance between images onscreen creates a variable illusion of depth. Because RealD uses polarization instead of the traditional red-and-cyan anaglyphs of the 1950s, it produces higher color saturation and sharper image resolution than its predecessor. RealD also alleviates the eyestrain and “ghosting,” or fringes of color around imperfectly aligned 3-D images, that bothered viewers of previous 3-D platforms, and it allows the viewer to turn or tilt her head without ruining the illusion. In short, RealD enables the 3-D viewer to experience herself as three-dimensionally enworlded, to inhabit the embodied spectatorial practice foreclosed by previous 3-D technologies. A viewer can now move in three dimensions while watching a movie that features and is about three-dimensionality; for the first time, she can experience 3-D vision as properly uncanny, rather than simply unwieldy.

* * *

Coraline engages RealD’s new three-dimensional visuality with a narrative about the problems of gender, vision, and identity. It dramatizes the chora line, or the contested genealogy of materiality and maternity, femininity and form. The movie begins when its eponymous young heroine (voiced by Dakota Fanning, see Figure 1) moves with her parents into the Pink Palace, a subdivided mansion outside Ashland, Oregon. Its opening vista also announces its entry into film history, because the establishing shot of the Pink Palace recreates Gregg Toland’s famous establishing shot of Xanadu, the stately pleasure-dome of Orson Welles’s Citizen Kane (1941) (see Figure 2). In Citizen Kane, Toland vertically pans up a series of increasingly ornate fences before Xanadu finally appears, an architectural behemoth, behind Charles Foster Kane’s monogrammed gate. The mansion reigns over a series of abandoned animals and pleasure craft like a warning: be careful what you wish for. Toland’s Xanadu is a matte painting, but its vertical stature and superimposed foregrounds nonetheless introduce the viewer to the film’s innovative deep-focus cinematography, the technique that would make both Toland and Citizen Kane legendary. Coraline cites this innovation through its establishing shot of a similarly menacing mansion on a hill, and its house likewise heralds the arrival of a new form of visual pleasure. For as the family’s silver VW Beetle weaves up through the foreground, past the sign for the Pink Palace and into Coraline’s new milieu, the viewer becomes aware of the various planes of image within a 3-D motion picture. The film thus draws on Toland’s celebrated deep-focus cinematography to contextualize RealD stereoscopy as another technological advancement in cinematic art. Citizen Kane becomes the background for Coraline’s 3-D gimmickry, the credential behind more typical conventions, such as aiming sewing needles and other protrusions at the viewer’s eyes.

Unfortunately, Coraline’s characters begin their adventures on a less optimistic note. Coraline’s parents (voiced by Terri Hatcher and John Hodgman) were recently involved in an automobile collision that the film implies may have been Coraline’s fault. Her mother is now confined to a neck brace and incapable of turning her head (unlike the viewer). Between unpacking and finishing an overdue writing assignment, she has little time to attend to her daughter’s loneliness and frustration, which only increase when Coraline meets her new neighbor, a know-it-all boy named Wyborn (voiced by Robert Bailey, Jr., see Figure 3). Wyborn—also known as Wybie—introduces himself by making fun of Coraline’s dowsing rod and calling her a water witch. He later apologizes by giving her a doll, but Coraline’s dissatisfaction continues to mount until she discovers a child-sized door hidden beneath the living room wallpaper. Her mother brusquely reveals the door’s bricked-over passageway, but Coraline’s neighbors—Mr. Bobinsky (voiced by Ian Shane), the irradiated and irrational shut-in in the attic, and Miss Spink and Miss Forcible (voiced by Jennifer Saunders and Dawn French), the bickering former burlesque queens who live in the basement—nonetheless warn her not to go through it. Naturally, Coraline goes to bed that night thinking of nothing else and subsequently dreams (or discovers) that the small door leads to an Otherworld.

This Otherworld is an exercise in cinematic spectacle and the uncanny wonders of RealD. Coraline’s transition into her new world begins when she follows one of Mr. Bobinsky’s never-before-seen trained mice and glimpses it disappearing, impossibly, behind the bricked-up door. When she opens the door, a long pillowy purple tunnel unfurls in front of her, its dynamic dilation suggesting that this is no ordinary vaginal passageway (see Figure 4).

In its 3-D undulations, the tunnel both resembles and surpasses the fleshy gates of hell that carry off little Carol Anne in Poltergeist (Tobe Hooper, 1982). Coraline might not appreciate that comparison, however, as she seems pretty touchy about her name; for some reason, the people in her real world keep calling her Caroline. Coraline soon discovers that in the Otherworld, everyone knows her name . . . and what she likes to eat and how she likes to garden and why she feels unsatisfied at home. Her spectacular reception begins in the kitchen, where her Other Mother (also voiced by Teri Hatcher) immediately greets Coraline with a cornucopia of delectable comfort foods and, with the help of Coraline’s Other Father (also voiced by John Hodgman), showers her with the attention she desperately craves. Entranced, Coraline soon returns to the Otherworld for more attention and s(t)imulation. Her Other Mother seems perfectly prepared to oblige, producing for Coraline a veritable wonderland of delights, delights that also happen to play to the strengths of RealD. At the Other Mother’s behest, Coraline’s Other Father flies her through a glowing garden of animated flowers and tickling vines (see Figure 5); later an ersatz Wybie escorts her to see Mr. Bobinsky’s mythical mouse circus (see Figure 6) and a revival of Spink and Forcible’s old burlesque acts, including a trapeze number in which they shed their aging, overweight bodies and emerge the starlets they may never have been.[4] These phantasmatic visions defy the laws of botany, biology, and physiology; they are wonders, and as such they emphasize the wonder of RealD cinema: reality, uncannily enhanced.

When Coraline returns from her tour, the Other Mother offers her an opportunity to join this spectacular world forever, but in order to become part of the ensemble, Coraline must give up her role as a spectator. Specifically, she must allow its matriarch to sew buttons over her eyes. In his essay on the uncanny, Freud encourages his reader to regard such threats as castration anxiety, but Coraline will pursue a less phallocentric metaphor. After Coraline refuses to become part of Other Mother’s world, she attempts to return to her “normal” world by going to sleep but quickly finds that she can no longer slip between states so easily. Coraline then tries to leave Other Mother’s terrain on foot and discovers that this world responds to laws of psycho-aesthetic—rather than terrestrial—distance. As Coraline marches away from the Other Mother’s unheimliches Heim, the woods around her devolve, becoming increasingly pale, unearthly, and abstract. At first, they seem to reveal themselves as images, specifically as storyboard sketches of trees, but later they dissolve entirely, leaving Coraline lost in a blank white field. Fortunately, a wise feral cat (voiced by Keith David) arrives to talk her through her predicament; he explains that the Other Mother “only made what she knew would impress you.” When Coraline asks why the Other Mother wants her so badly, the cat corrects her solipsism; the Other Mother does not desire Coraline specifically, just “someone to love—I think. Something that isn’t her. Or maybe she’d just love something to eat.”

Coraline finds out precisely what that means when she and the cat arrive right back where they started. Enraged by Coraline’s resistance, the Other Mother throws her through a mirror into a dimly lit holding cell between image regimes until she can “learn to be a loving daughter.” Had she read her Freud, Coraline might recognize the Other Mother’s conflicting desires as incorporation, as the desire to fuse with and cannibalize a love-object (see Freud, Totem and Taboo). During incorporation, the subject takes in an outside object but cannot integrate it. As Derrida explains, such abortive assimilations both fortify and threaten the ego:

Incorporation is a kind of theft to reappropriate the pleasure object. But that reappropriation is simultaneously rejected: which leads to the paradox of a foreign body preserved as foreign but by the same token excluded from a self that thenceforth deals not with the other, but only with itself. (xvii)

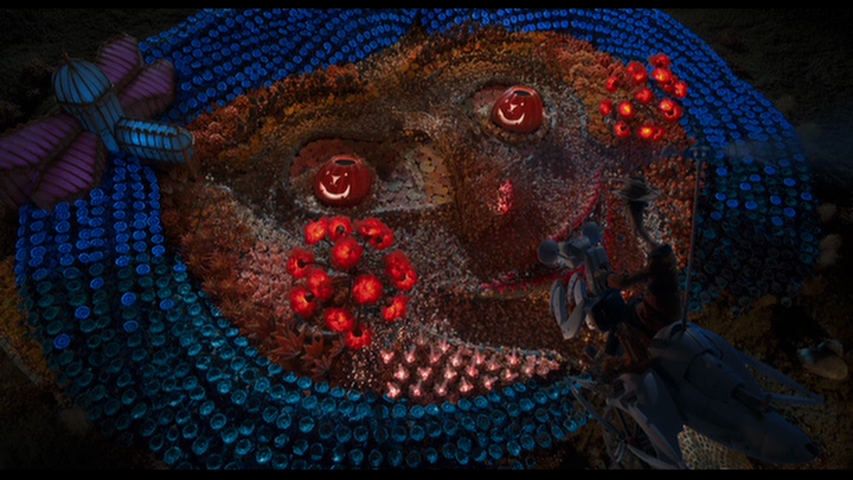

To wit: the Other Mother confines Coraline to the mirror room, her chamber of incorporation—what Derrida calls “the crypt . . . the vault of desire” (xiv)—both to exile and to contain her. There Coraline meets the Other Mother’s other “children,” all of whom have given up their eyes to the Other Mother, whom they call the Beldam. The Other Children explain to Coraline that after they let the Beldam sew buttons over their eyes, they forgot their names and eventually lost their bodies as well—a cryptic introduction to matter and metaphysics, if you will. The ghosts beg Coraline to find their eyes and thereby release what remains of their souls, but she demurs until she discovers that the Beldam has trapped her parents in a snowglobe. Then, armed with a magic monocle made of salt-water taffy, Coraline returns to the Otherworld to reexamine the three spectacles that previously captivated her: the garden, the mouse circus, and the burlesque show. Each one turns out to be animated by a brightly colored marble (one of the ghosts’ eye-souls), but when Coraline confronts the Beldam with her plunder, the witch does not simply release her prisoners as promised. Instead, she shatters the illusory Otherworld and reveals the sticky spider’s web undergirding its architecture of incorporation. Here, RealD and Renaissance perspective unite to reveal the depth of the trap Coraline has wandered into (see Figure 7). Coraline tries to climb the sides of this monstrous grid, but her only egress is the vaginal tunnel, now brown, desiccated, and cluttered with cobwebs. When Coraline tries to close the door on this barren canal, she inadvertently catches the Beldam between worlds, severing the Beldam’s right hand. In the film’s dénouement, Coraline must dispose of this claw by returning it to another infertile vagina, this time an abandoned well. Only then are the Pink Palace and its occupants safe from feminine incorporation.[5]

* * *

Throughout this narrative, Coraline’s figural focus on webs, wells, caves, and portals unifies its metaphoric and technological interests. As Wired columnist Frank Rose observes, the digital 3-D “is even better [than its predecessors] at sucking you in—into the endless shadows of a cave or into the vortex of a shrieking face.” Scott Higgins notes that Coraline capitalizes on 3-D cinema’s “shoebox diorama effect as an aesthetic choice rather than as a deficiency . . . by exploring flamboyant depth effects that remain anchored to character experience” (200). These effects also allow the film to comment on Western theories of perspective that have long emphasized depth over protrusion. From Leon Battista Alberti’s De pictura (1435) to the contemporary cinema screen, dominant representational traditions have conditioned viewers to experience the film image as a window, and the very physics of projection make it extremely difficult for a film image to successfully occlude that frame and appear to pop into the theater.[6] For that reason, stereoscopic illusions of depth have always looked more believable than emergence effects, which extend images out at the audience. In fact these would-be protuberances are recognizable as a convention of US 3-D filmmaking precisely because of their failure, because they make the spectacle of 3-D visible instead of blending into the diegesis. Coraline’s many caverns and cavities do not exactly disappear into the narrative either, but they make visible the narrative’s investment in what its technology makes possible. Moreover these stereoscopic vaginal spectacles reveal how contemporary philosophical debates about the chora elucidate recent crises of faith regarding the post-cinematic image, particulary the crisis of form and indexical reference brought on by digital media.

The chora—or khōra—refers to the metaphysical crucible in which form is imprinted on matter, “the space within which the sensible copy of the intelligible is inscribed” (Caputo 99). The term originates in Plato’s Timaeus, during the eponymous character’s discourse on the origin of the universe: how demiurge created the gods, who were unchangeable and unchanging, and the world, which changes. In this cosmology, ideal and unchanging Form must be imparted to changeable Matter. The space within which this happens, although part of Matter, cannot take on any of the Forms that pass through it; thus Timaeus characterizes this space—or interval, since it represents both a physical and a temporal alterity—as that which “comes to be but never is” (par. 27d).[7] It exceeds representation and cannot possess any characteristics of its own, yet somehow it still seems to have a gender—or rather its narrator is unable to conceive its passivity outside a binary gender system. As “the receptacle of all material bodies,” the chora is inherently both unintelligible and feminine:

[T]he mother and receptacle of every created thing, of all that is visible or otherwise perceptible, we shouldn’t call it earth or air or fire or water, or any of their compounds or constituents. And so we won’t go wrong if we think of it as an invisible, formless receptacle of everything. (par. 51a)

Elsewhere, Timaeus describes the chora as “the nurse of creation” (52d) that can only be “grasped by a kind of bastard reasoning” (52b). These metaphors, although not intended to describe the chora as it actually is, nonetheless produce a system of associations based on female anatomy and patriarchal interpretations of femininity. They thereby reduce both the chora and the feminine to passive and unimpressionable blankness.

In recent years, some French, Australian, and US theorists have reinvigorated chora as a key concept for understanding the exclusion of women and the feminine from Western metaphysics, an exclusion that characterizes Coraline’s Other Mother as well. These reinvestigations, most profitably led by Luce Irigaray, Elizabeth Grosz, and Judith Butler, often begin by departing from Jacques Derrida’s reading of khōra as the ungendered, inassimilable origin of différance in Western philosophy. For Derrida, khōra is an aporia, that which philosophy cannot incorporate and is undeserving even of a definite article:

The definite article presupposes the existence of a thing, the existent khōra to which, via a common name, it would be easy to refer. But what is said of the khōra is that this name does not designate any of the known or recognized or, if you like, received types of existent. (236)

Because “what there is, there, is not,” khōra cannot have a gender, which means—according to Derrida—that all the gendered metaphors Timaeus uses to describe khōra are catachreses; they mislead the reader into an overly definite sense of khōra’s nature.[8] For Derrida, Plato’s feminine figures only represent barred destinations of incorporational desire; like the children the Other Mother craves, they are held at a distance that both underscores their inadequacy and sustains a fantasy of materialization.

Derrida’s attempt to cleanse khōra of gender has been rebuked by an international coterie of feminists, whose critiques contextualize my reading of the Beldam as a figure of the chora’s disavowed epistemological value, labor, and desires. For instance, Julia Kristeva uses the chora to describe the psychical space and developmental process of signification, a process in which the mother plays a pivotal role. In the chora stage, an infant both finds all its needs satisfied by a (nondifferentiated) maternal body and experiences the first breaks between itself and that material plentitude. These breaks initiate the process of semiogenesis and subjectification (Kristeva 37). Kristeva emphasizes that “the mother’s body is therefore what mediates the symbolic law organizing social relations,” making it “the ordering principle” that precedes and underlies figuration and specularization (37). Her reading interprets Derrida’s extra-grammatical aporia as the founding state of semiosis and inaugurates an important debate about the chora’s gender (Is it maternal? Is it feminine?) and its ideological role (Can it experience desire or only produce it?) that ground other feminist interpretations of the chora and my reading of the Beldam.

Many feminist philosophers read the chora as a symptom—even the origin—of the routine exclusion of the feminine from Western (which is to say patriarchal) metaphysics of representation. Historically, this critique begins with Luce Irigaray; as Judith Butler explains, Irigaray understands the chora to be “what must be excluded from the domain of philosophy for philosophy itself to proceed” (37), but she reads that exclusion as the very process through which the chora becomes (dis)figured as the feminine. Irigaray argues that feminine metaphors for the chora are both catachreses and precisely on point: to the extent that the chora’s role in figuration can be understood as “participation by the non-participant” (Irigaray 175), it makes the female present only to exclude it from the process of generation.[9] In other words, the chora manifests the patriarchal metaphysics endemic to Western theories of representation. As a metonymy for the maternal—and thus the feminine—in the origins of Western metaphysics, the chora dehumanizes, disempowers, and dematerializes women, placing them outside the real in some Other Space. Like the Other Mother, the chora exists beyond and beneath material existence and makes the latter possible, but only to be excluded from it. Her necessity contains the terms of her exile, and as Coraline suggests, any conscious resistance to that ontological servitude amounts to villainy.

Coraline is a movie about world-building, about the desires behind the image and its relationship to space, and the Other Mother captures the ways that women have systematically served and been excluded from that discourse. The Other Mother is the chora endowed with voice and rage. In “Woman, Chora, Dwelling,” Elizabeth Grosz contends that Western philosophers designate the chora as a kind of barren femininity, an ungrounded, unspecified condition that can generate but cannot participate, “whose connections with women and female corporeality have been severed, producing a disembodied femininity as the ground for the production of a (conceptual and social) universe” (113). This nonspecificity marginalizes the feminine and essentially reverses its generative powers: “Though she [the chora] brings being into becoming she has neither being nor the possibilities of becoming; both the mother of all things and yet without ontological status, she designates less a positivity than an abyss” (Grosz 116). Once the chora is designated an abyss, its labor is systematically obfuscated and the chora can be dismissed as “a space of duty, of endless and infinitely repeatable chores that have no social value or recognition, the space of the affirmation and replenishment of others at the expense and erasure of the self” (Grosz 122). As part of an origin story for the universe, then, the chora both does work and obscures work, the work required of women for the perpetuation of their own effacement.

* * *

Were she a philosopher, the Beldam might make a similar point: endlessly engaged in a production of the sensible, she exists as that which must be expelled and repressed for the real world to maintain its heteronormative futurity. Like the chora, she is an Other Mother vilified for her (allegedly) illegitimate desire to take in or take on materiality. Constantly looking for something to call her own, she tries to incorporate spectators into the worlds she materializes for them, but once they become hers, she finds that they are not enough: being cannot live up to form. Thus although she identifies herself as an Other Mother, it is equally helpful to call her by her other name: the Beldam. Originally used to designate any great- or grand-mother, by 1586 beldam began to refer to “any aged woman,” but especially “a loathsome old woman, a hag; a witch, [and] a furious raging woman.”[10] Thus she is both a figure of nurturance and reproduction and explicitly marked as barren. As Coraline’s Other Mother, the Beldam represents both the return of the maternal plenitude Coraline’s real mother cannot offer her (because she has a job and because Coraline is no longer an undifferentiated infant) and the threat of that plenitude. The Beldam is jouissance, and she makes jouissance visible through her ultimate annihilation of the symbolic Otherworld.

The Beldam is also the force of creation that begins Coraline and establishes its metaphysical conceit and stereoscopic aesthetic. Although the viewer does not know it at the time, the Beldam is actually the first character to appear in the movie, which begins with two disembodied needle-hands deconstructing a young girl doll via fantastic emergence effects. Viewers do not meet the Beldam face-to-face until Coraline goes through the portal into the Otherworld where the Beldam is once again cooking something up, trying to entice Coraline with her ideal home-cooked meal. At her first appearance, then, the Beldam creates an existential crisis for Coraline, who must learn to value material reality over virtual ideals.[11]

Belief in ideal forms is precisely what trapped the three Other Children, who haunt Coraline as narrative and figural failures. They failed to appreciate their imperfect material lives and to discern the Beldam’s desire, which is how they became trapped in her world of illusions. They are also aesthetic failures, their dialogue mawkish and their models hackneyed and unattractive. Nonetheless, the precise nature of their figural failure enables important observations about the film’s metaphoric investment in celluloid materiality. When Coraline first discovers the Other Children, hiding under a sheet inside the Beldam’s mirror-limbo, they resemble bobbing balls of light. After Coraline exposes the Other Children, they start to float and flicker around her, their images ghosting like bad 3-D anaglyphs. In short, the movie uses a defect of stereoscopic celluloid cinematicity to suggest that these children have passed away. Whereas Coraline’s model exudes reliable material fortitude, the Other Children flicker, like poorly projected film, and thereby connote death within the film, the death of film, and the death that has always haunted film. Their limbo is the lifedeath Alan Cholodenko describes as undergirding all animation, “the spectre in the screen [that] gives all form, but is ‘itself’ never given as such” (“The Spectre” 47). The ghost children invite one to reread the cinema for the inanimation haunting all animation, to regard the projector as an apparatus that gives existence to intelligibility, that—like the chora—must be excluded from the representable world and its animating principle.

Yet by setting the ghost children apart as failures, Coraline reverses the power structure inherent in animation’s lifedeath and Plato’s chora. Unlike her precedents, Coraline’s Beldam is both a crucible of materiality and spectacle and capable of divorcing intelligibility and sensibility when she feels she is not being appreciated. As Coraline races to defuse the Beldam’s world of wonders, the Beldam vents her frustration by dematerializing it, first erasing color and then tearing up the woods and gardens around her Pink Palace, leaving only a gray haze (see Figure 8).

This ruination very much resembles a conceptual inversion of Dorothy’s escape from the grey plains of Kansas in Victor Fleming’s Wizard of Oz (1939), as now the Technicolor Oz is being pulled out from under the little girl who could not appreciate it. Inside the Pink Palace, the Beldam demolishes her domestic spectacle as well, ripping up the floorboards and stripping the paper from the walls. Previously, the Beldam had always been an engine of materialization; now she throws that engine into reverse, the maternal jouissance withdrawing its previous support of the symbolic and thus destructuring her world. To be sure, Coraline does not sympathize with the Beldam in this rebellion; it represents her exposed web as a space of decay and absorption (desanguinated bugs and all). When the chora demands acknowledgement for her work, Coraline characterizes it as a space of selfish reception. Thus it leaves the Beldam trapped alone in her own web, blind and maimed, even as it gives her a chance to articulate her desire: “Don’t leave me, don’t leave me. I’ll die without you.” Coraline is hardly sympathetic to the chora’s line (what child wants to hear that its mother has needs too?), but by offering its material functionary a chance to explain, the movie indicates a desire to understand its own uncanny animating principle. Like the filmmakers themselves, the Beldam has brought dolls and worlds to life for her spectator’s amusement. Coraline rejects such ersatz-worlds as crypts she can escape from. She would like to believe that by exiting the Beldam’s web she can exit the system, but Coraline suggest incorporation is not so easy to evade.

* * *

To be more precise, Beldam’s desire to incorporate Coraline into her crypt exposes a political uncanniness in stop-motion animation and ultimately digital 3-D as well. Derrida suggests that during incorporation, “[t]he dead is taken into us but doesn’t become a part of us. It occupies a particular place in our body. It can speak on its own. It can haunt and ventriloquize our own proper body and our own proper speech” (qtd. in Cholodenko, “The Crypt” 101). Derrida’s metaphor also describes the excessive material presence through which stop-motion becomes political—the way in which it materializes and excessively animates the social world that produced it. As Sianne Ngai has suggested, replacement animation enables past—but evidently not dead—stereotypes about the racialized body to erupt across its surfaces. Coraline toys with the trope of animatedness that Ngai unpacks and extends her theory of excessive animation to the feminine, the chora, and thus the impact of Western metaphysics on post-cinematic systems of representation.

Ngai pursues the political implications of excessive animation—which she calls animatedness—as “one of the most ‘basic’ ways in which affect becomes publicly visible in an age of mechanical reproducibility . . . a kind of innervated ‘agitation’ or ‘animatedness’” (31). Tracing excessive animatedness through nineteenth- and twentieth-century US cultural production, Ngai borrows Rey Chow’s figure of the “postmodern automaton” to read stop-motion as a metaphor for the mechanization of the female and working-class body under modernity. Chow contends that modern visual culture provides both the logic and the locus for contemporary regimes of difference, that “the visual as such, as a kind of dominant discourse of modernity, reveals epistemological problems that are inherent in . . . the very ways social difference—be it in terms of class, gender, or race—is constructed” (55). Specifically, Chow argues that “One of the chief sources of the oppression of women lies in the way they have been consigned to visuality . . . which modernism magnifies with the availability of technology such as cinema” (59-60). Ngai argues that different forms of visual production engender different modes of constructing the other and that stop-motion “calls for new ways of understanding the technologization of the racialized body” (125). Ngai goes on to examine how the body becomes a technological object for the performance of race (or, one might argue, for the performance of maladaption to US racism) in FOX’s stop-motion sitcom, The PJs (1998-2001). Chronicling the misadventures of a disenfranchised public-housing community in Detroit, The PJs requires characters’ mouths to move very quickly to deliver its comedic dialogue, yet such rapid replacement animation leads to visible modular instability. As conversations progress, characters’ mouths become excessively mobile, even volatile, and for Ngai, this excessive animation suggests “an exaggerated responsiveness to the language of others that turns the subject into a spasmodic puppet” (32). Such unintended animation contributes to the show’s critique of racism, as “in its racialized form animatedness loses its generally positive associations with human spiritedness or vitality and comes to resemble a kind of mechanization” (32). Excessive animatedness thus elevates stop-motion above the innocuousness of advertisements and children’s programming and emphasizes the genre’s commentary on the social body, on the body as a cog conditioned by the social machine.

Ngai’s analysis of The PJs marks a significant break with previous analyses of stop-motion animation, which tend to focus on its industrial history and its uncanny timelessness. Indeed, not only does Ngai call attention to the social and political implications of animation as a technology of vision, but she also suggests that the uncanniness of animation metonymizes the uncanniness of the subject under industrialized capital. In the twenty-first century, this subject no longer produces wealth through labor but struggles with quandaries of consumption, representation, and virtual existence. Coraline exposes this production of difference through its representation of African-American characters not present in Neil Gaiman’s original novel. These characters, Wyborn Lovat and his grandmother, own the Pink Palace where Coraline lives; in fact, the film hints that Ms. Lovat (voiced by Motown artist Carolyn Crawford) began fighting the Beldam long before Coraline arrived. Ms. Lovat only chimes in as an off-screen voice for most of the movie, but when she finally does appear, her skin color and accessories make race retroactively visible in the film. Indeed, Ms. Lovat marks Wyborn as African-American for audience members who may not previously have acknowledged him as such. For although Wyborn is the only brown character in most of the film, another is blue-skinned, and others have blue hair, so his brown skin and brown mop-top may not suggest blackness to a viewer not used to recognizing race in animation. With the arrival of Ms. Lovat, the race that was always implicit in Wyborn’s excessive animation becomes visible. Not only does Ms. Lovat look darker than Wyborn, she also physiologically resembles a PJs character. She even wears a gardenia in her hair, an homage to both Billie Holiday and Hattie McDaniel, who wore the flower while accepting her 1939 Academy Award for Best Supporting Actress.

For the spectator who has been looking for it, however, race has always been visible in Coraline, politicizing its animation from the opening scenes of the movie. Its first shot depicts an African-American doll floating down through an open window to be grasped by the Beldam’s needle-fingers. These hands then begin dissembling the doll’s clothes and features, removing form from matter, before exposing the hegemonic whiteness of US film by reconstituting the doll as Caucasian (and specifically as Coraline). This (de)materialization sequence is crucial for the movie’s artistic and political projects because it binds the production and obfuscation of race in Coraline to its new 3-D aesthetic. The scene works on the doll—and the viewer—with both classic 3-D projectiles (in this case a needle poking up through the doll’s button-eye and waving toward the viewer) and deep focus shots of the doll descending into and floating out of an open window. These virtual expansions of screen space inaugurate a new approach to 3-D visuality, wherein the screen becomes a receptacle for the nebulous materialization of the image. Because this prologue reinscribes screen space as receptacle during a scene of feminine production, moreover, it fosters a political association between chora, race, and materiality in animation that frames the film’s depiction of its central African-American character, Wyborn.

Wyborn first arrives in Coraline dressed as a “spook”; outfitted to resemble a ghost, in a black fireman’s coat and a welder’s mask painted to resemble a skull, he appears on top of a cliff, rearing up his bicycle as lightning crashes and Coraline gasps. Once she recovers from her fright, Coraline immediately begins undermining—or unpacking—Wyborn’s name; she ignores his preferred nickname, Wybie, and calls him “Why-were-you-born” instead. As cunning as this sobriquet might sound, it obscures the degree to which the film uses race to signal ontological uncertainty. Not only is Wyborn an annoyingly animate little boy, he is also excessively tied to the film’s representation of its own animation process. Wyborn unwittingly brings the Beldam’s doll to Coraline, and his gift reminds the spectator that Coraline is herself a doll while naturalizing her dollhood by comparison. Wybie also becomes the model against which Coraline’s animatedness develops, where animatedness is defined (by Ngai) as “threatening one’s own limits (or the roles in which one is captured and defined) not by transcending these limits from above but by inventing new ways of inhabiting them” (124). In the Otherworld, the Beldam produces an Other Wyborn to guide Coraline through her cinema of attractions; however, this Wyborn’s mouth is sewn into an exaggerated rictus that emphasizes the horror of being animated (as opposed to being animate). Thus Wyborn’s name and his epistemological role in the film indicate his centrality for understanding the greater visual and material crisis in Coraline. Wyborn brings out the animatedness in Coraline and in Coraline; his character produces the connection between Selick’s movie and Ngai’s affect theory that ultimately unveils the contemporary stakes of the chora for digital mediation.[12]

Thus Wyborn’s politicized embodiment helps the spectator understand Coraline’s architecture as a film and its commentary on contemporary theories of gendered architecture and materialized form. Coraline draws its viewer into the experience of scenic space and narratively thematizes that experience, and by attending to that intersection, we can better understand our spectatorial investment in digital 3-D. Coraline reminds its viewer that embodied experiences of vision and animatedness do not come without social conditioning. It reproduces the lived experience of biocular vision as virtual and fantasmatic and in so doing, it allows the spectator to acknowledge that such embodied participation in vision is necessarily uncanny. Simultaneously, it proffers the chora as the guiding structure of a paradoxical desire for incorporated spectacle and incorporation into spectacle. The film thus enables viewers to experience the desire for RealD as an extension of an existing trope for understanding the deep interweaving of gender and representation that persists into the digital. Moreover, Coraline’s return to the uncanny trope of the chora can direct us toward a new theory for the uncanniness of digital spectatorship and a new investment to replace many viewers’ loss of faith in the photographic index.

* * *

Coraline negotiates the relationship of form to matter no matter which platform one sees it on, but its significance for spectatorial investment in digital cinema is most pronounced when the film is exhibited in RealD. Through Coraline, the RealD viewer receives a visual exercise in the relationship of image to matter for digital cinema; the film provides metaphors for those questions through its narrative and its excessively digital and excessively material production techniques. Coraline’s figural and dramatic chora invites the spectator to reconsider the crisis facing cinematic indexicality. Since the early 1980s, media critics have questioned how digital image capture, processing, and exhibition—and their allegedly “infinite capacity” to manipulate an image—would affect the truth-value of photochemical photography. Such ruminations demonstrate that digital imagery has undermined the spectator’s historical faith in the photograph as indexical record. As Philip Rosen explains, photographic indexicality—“minimally defined as including some element of physical contact between referent and sign”—represented the standard of historiographic probity from roughly the 1830s through the 1980s, but lately its credibility has come unmoored (302). Rosen points out that digital image production and exhibition do not necessarily carry their viewer any further from the profilmic referent than analog transcription, but they may make the image’s capacity for duplicity more visible. Popular US film genres have also shown a marked predilection for “digital mimicry,” exploiting CGI’s capacity for hyperrealism in blockbusters like Independence Day (Roland Emmerich, 1996), Spider-Man (Sam Raimi, 2001), and Transformers (Michael Bay, 2007) (see also McClean). These films use digital image production to bolster photorealism, and thus indexicality, as a representational norm or standard, even as indexicality also stands as the limit they must overcome (Rosen 309). Moreover, the very crispness and “perfection” of computer graphics also induce digital skepticism that prevents many post-cinematic spectators from psychically investing in digital projection. As Sobchack so eloquently explains, the cold perfection—the “deathlife”—of computer animation fails to provide its viewers with any substitute for or diversion from the loss of the impossible fantasy of indexicality (180).

Coraline incorporates this “deathlife”—or digital uncanny—into its third dimension; it constructs the 3-D screen as receptacle for a new experience of form and matter. It exploits the instability of the index while experimenting with the chora as a potentially more useful metaphor for the relationship of image to matter for this platform. Recall that Coraline was made with digital stop-motion, with digital illustrations that produced plasticine models that later became digital photographs. The movie’s whole technique is premised on the uncanniness of the motion picture’s precarious relationship to indexicality, but it also creates an image that can reassure the viewer that there is a referent for digital 3-D’s uncanny screen depth. At root, the trouble with RealD—like 2-D digital imagery before it—is its uncanny loss of indexicality: how can a digital motion picture reproduce the viewer’s faith in a mimetic image famously devoid of film’s characteristic indexical trace? Stereoscopic visual technologies aim to produce a more material experience of vision than their two-dimensional counterparts, but digital 3-D projection does so—and does so more successfully—by (further) cleaving the image from material, profilmic referents. Lev Manovich, D.N. Rodowick, and others have already demonstrated that the digital photograph is neither more nor less indexical than the chemical photograph, but Coraline precipitates a new theory of digital spectatorship based on the historically unstable relationship of form to matter. In Coraline, the chora returns to replace the index as the dominant metaphor for the relationship of image to matter in cinema. It does so through RealD’s illusory spaces and its stop-motion dolls’ uncanny physicality. By mimicking materiality on screen, Coraline provides the spectator with a locus—a stain, if you will—in which to locate her anxieties about visuality and material existence.

Even if the juggernaut of Hollywood studio marketing succeeds in overshadowing Coraline and relegating it to the footnotes of future histories of digital stereoscopy, this low-budget independent animation nonetheless constitutes a pivotal moment in the history of digital projection, an important metacinematic contemplation of the pleasure of post-cinematic spectatorship. The movie not only positions its new exhibition platform in relationship to previous cinematic innovations like deep focus, it also enables us to see digital cinema through older philosophical inquiries into the relationship of image to matter. Moreover, the political overtones of its production medium should remind the spectator that “the production of the West’s ‘others’ depends on a logic of visuality that bifurcates ‘subjects’ and ‘objects’ into the incompatible positions of intellectuality and spectacularity” (Chow 60)—or in the case of the chora, into incompatible categories of intelligibility and femininity. Coraline allows us to screen the problematic tropes governing Western metaphysics of visuality; it reminds us that these issues condition our relationship to the image just as much as the RealD spectacles perched over our eyes. Like the Beldam, we have filled our virtual receptacles with ghosts who whisper: the pleasures of new media are built on ancient regimes of power and visuality.

Works Cited

“3D.” Box Office Mojo. Web. <http://boxofficemojo.com/genres/chart/?id=3d.htm>.

“Avatar.” Box Office Mojo. Web. <http://boxofficemojo.com/movies/?id=avatar.htm>.

Bond, Paul. “RealD CEO Michael Lewis.” Interview with Michael Lewis. Hollywood Reporter, 16 Aug. 2011. Web. <www.hollywoodreporter.com/news/reald-ceo-michael-lewis-223427>.

Bordwell, David. Pandora’s Digital Box. Web. <www.davidbordwell.net/books/pandora.php>.

Butler, Judith. Bodies that Matter: On the Discursive Limits of Sex. New York: Routledge, 1993. Print.

Caputo, John D. Deconstruction in a Nutshell: A Conversation with Jacques Derrida. New York: Fordham UP, 1997. Print.

Cholodenko, Alan. “The Crypt, The Haunted House, of Cinema.” Cultural Studies Review 10.2 (2004): 99-113. Web. <http://epress.lib.uts.edu.au/journals/index.php/csrj/article/view/3474/3612>.

—. “The Spectre in the Screen” Animation Studies 3 (2008): 42-50. Web. <http://journal.animationstudies.org/wp-content/uploads/2008/10/ASVol3Art6ACholodenko.pdf>.

Chow, Rey. Writing Diaspora: Tactics of Invention in Contemporary Cultural Studies. Bloomington: Indiana UP, 1993. Print.

Cowan, Matt. “3D Glossary.” RealD—The New 3D. 1 Feb. 2008. Web. <www.reald.com/Content/Presentations.aspx>.

Creed, Barbara. The Monstrous Feminine. New York: Routledge, 1993. Print.

Derrida, Jacques. “Fors: The Anglish Words of Nicolas Abraham and Maria Torok.” The Wolf Man’s Magic Word: A Cryptonomy. Trans. Barbara Johnson. Minneapolis: U of Minnesota P, 1986. Print.

Elsaesser, Thomas. “The ‘Return’ of 3-D: On Some of the Logics and Genealogies of the Image in the Twenty-First Century.” Critical Inquiry 39.2 (2013): 217-46. Print.

Foreman, Adrienne. “A Fantasty of Foreignness: The Use of Race, Ethnicity, and Gender to Solidify Self in Henry Selick’s Coraline.” Red Feather Journal 3.2 (2012): 1-15. Print.

Freud, Sigmund. Totem and Taboo. Trans. James Strachey. New York: Norton, 1990. Print.

—. “The Uncanny.” The Pelican Freud Library, vol. 14. Eds. Albert Dickson and James Strachey. Trans. James Strachey. New York: Penguin, 1985. Print.

Friedberg, Anne. The Virtual Window: From Alberti to Microsoft. Cambridge: MIT P, 2009. Print.

Grosz, Elizabeth. “Woman, Chora, Dwelling.” Space, Time, and Perversion: Essays on the Politics of Bodies. New York: Routledge, 1995. Print.

Halberstam, Judith. The Queer Art of Failure. Durham: Duke UP, 2011. Print.

Higgins, Scott. “3-D in Depth: Coraline, Hugo, and a Sustainable Aesthetic.” Film History 24.2 (2012): 196-209. Print.

Irigaray, Luce. Speculum of the Other Woman. Trans. Gillian C. Gill. Ithaca: Cornell UP, 1985. Print.

Kristeva, Julia. “The Semiotic and the Symbolic.” The Portable Kristeva. Ed. Kelly Oliver. Trans. Margaret Weller. New York: Columbia UP, 2002. Print.

McClean, Shilo T. Digital Storytelling: The Narrative Power of Visual Effects in Film. Cambridge: MIT P, 2008. Print.

McClintock, Pamela. “Studios, Theaters Near Digital Pact.” Variety 10 Mar. 2008. Web. <www.variety.com/article/VR1117982175.html?categoryid=2502&cs=1>.

Myers, Lindsay. “Whose Fear Is It Anyway?: Moral Panics and ‘Stranger Danger’ in Henry Selick’s Coraline.” Lion and the Unicorn 36.3 (2012): 245-57. Print.

Ngai, Sianne. Ugly Feelings. Cambridge: Harvard UP, 2005. Print.

Plato. Timaeus and Critias. Trans. Robin Waterfield. New York: Oxford UP, 2008. Print.

Rose, Frank. “Beowulf and Angelina Jolie Give 3-D a Second Chance in Hollywood.” Wired 15.11, 23 Oct. 2007. Web. <www.wired.com/entertainment/hollywood/magazine/15-11/ff_3dhollywood>.

Rosen, Philip. Change Mummified: Cinema, Historicity, Theory. Minneapolis: U of Minnesota P, 2001. Print.

Sobchack, Vivian. “Final Fantasies: Computer Graphic Animation and the [Dis]Illusion of Life.” Animated Worlds. Eds. Suzanne Buchan, David Surman, and Paul Ward. Bloomington: Indiana UP, 2006. Print.

Wells, Paul. Animation: Genre and Authorship. New York: Wallflower, 2002. Print.

Notes

The author wishes to thank South Atlantic Quarterly for permission to adapt this article from a 2011 special issue on “Digital Desire” edited by Ellis Hanson.

[1] Digital 3-D movies can make three times as much per screen as their 2D versions, which explains why distributors and exhibitors embraced digital projection. In the early 2010s, distributors also offered exhibitors financing packages to subsidize their transition to digital projection. See Rose; Bordwell.

[2] Coraline thus resolves the shortcomings of digital animation that Sobchack identifies in her case study of the early digital feature Final Fantasy: The Spirits Within (2001), which she argues failed (both critically and financially) because it removed the indexical trace of hand-drawn cel animation without providing an alternative locus for the uncanniness of cinemagraphic motion.

[3] To be clear, I am arguing that Coraline progressively—even radically—reinterprets an age-old patriarchal trope of Western metaphysics. I am aware that other critics critique this film for its allegedly conservative, even reactionary gender representations. However, these scholars focus almost exclusively on the film’s central character and her narrative without considering its animation or stereoscopic techniques. Thus they miss its important formal experiments with representation as such. See Halberstam; Myers.

[4] This sequence is bawdy, but just bawdy enough, because Coraline cannot afford either a G or a PG-13 rating in the US. While G indicates a film is appropriate for “general audiences,” PG-13 suggests that it may contain objectionable violence, sexual activity, or language. PG’s “parental guidance” warning suggests that a film will be neither tediously tame nor offensively titillating, making it the most profitable and hence most desirable rating for many US filmmakers. While analyzing the corporate deal that would bring RealD to Regal, Cinemark, and AMC theaters across the US by 2009, Variety columnist Pamela McClintock cites a recent study by Nielsen Co. that discovered that “family-friendly, PG-rated films without profanity generated the best box office results.” McClintock’s article ties PG-ratings to RealD as the financial future of the studio system; indeed, eight of the top ten RealD movies have been rated PG or PG-13. See also Box Office Mojo’s article on “3D.”

[5] Barbara Creed offers perhaps the most cogent analysis of femininity, Freudian incorporation, and maternal monstrosity in The Monstrous Feminine, wherein she points out that many cultural narratives about subject-formation hinge on the defeat of a mother’s consuming desire.

[6] For more on window metaphors in Western visuality, see Friedberg.

[7] He goes on to explain that “it only ever acts as the receptacle for everything, and it never comes to reassemble in any way whatsoever any of the things that enter it” (par. 50c).

[8] Derrida writes, “To that end, it is necessary not to confuse it in a generality by properly attributing to it properties which would still be those of a determinate existent, one of the existents which it/she ‘receives’ or whose image it/she receives: for example, an existent of the female gender—and that is why the femininity of the mother or the nurse will never be attributed to it/her as a property, something of her own” (237).

[9] She contends that “[chora] is an approximate name chosen for a general conception; there is no intention of suggesting a complete parallel with motherhood . . . by a remote symbolism, the nearest [its philosophers] could find, they indicate that Matter is sterile, not female to full effect, female in receptivity only, not in pregnancy” (179).

[10] Oxford English Dictionary, 2nd ed., s.v. “beldam,” Online at: <http://dictionary.oed.com/cgi/entry/50019862>.

[11] This is where my reading of Coraline departs from those of Judith Halberstam and Lindsay Myers, who consider Coraline a fundamentally conservative film. Halberstam argues that Selick’s movie is “about the dangers of a world that is crafted in opposition to the natural world of family and the ordinary” (180). In fact, the Otherworld is crafted to reflect the ideology dominating Coraline’s real world, the ideology she must learn to see past. Halberstam’s reading ignores Coraline’s growth over the course of the film; Coraline’s adventures in the Otherworld teach her to reject the heteronomativity she thought she wanted and to value community as much as her own ego-satisfaction.

[12] Adrienne Foreman draws our attention to a third, more problematic use of racialized imagery in Coraline, namely the mystical black cat voiced by Keith David. Foreman suggests that “the cat is racialized in his position as well as his voice” because he plays the role of “the magic negro” whose supernatural powers help the white protagonists achieve her goals (12). The cat is the first character to see through the Beldamn’s tricks, suggesting perhaps the crucial role race needs to play in our understanding of politicized regimes of vision.

Caetlin Benson-Allott is Director and Associate Professor of Film and Media Studies at the University of Oklahoma. She is the author of Killer Tapes and Shattered Screens: Video Spectatorship from VHS to File Sharing (2013) and Remote Control (2015). Her work on spectatorship, video technologies, sexuality, and genre has appeared in Cinema Journal, Film Quarterly, the Journal of Visual Culture, and Feminist Media Histories, among other journals, and in multiple anthologies.

Caetlin Benson-Allott, “The Chora Line: RealD Incorporated,” in Denson and Leyda (eds), Post-Cinema: Theorizing 21st-Century Film (Falmer: REFRAME Books, 2016). Web. <https://reframe.sussex.ac.uk/post-cinema/3-3-benson-allott/>. ISBN 978-0-9931996-2-2 (online)