Phonographic Voices (i)

1May 8, 2014 by Richard Elliott

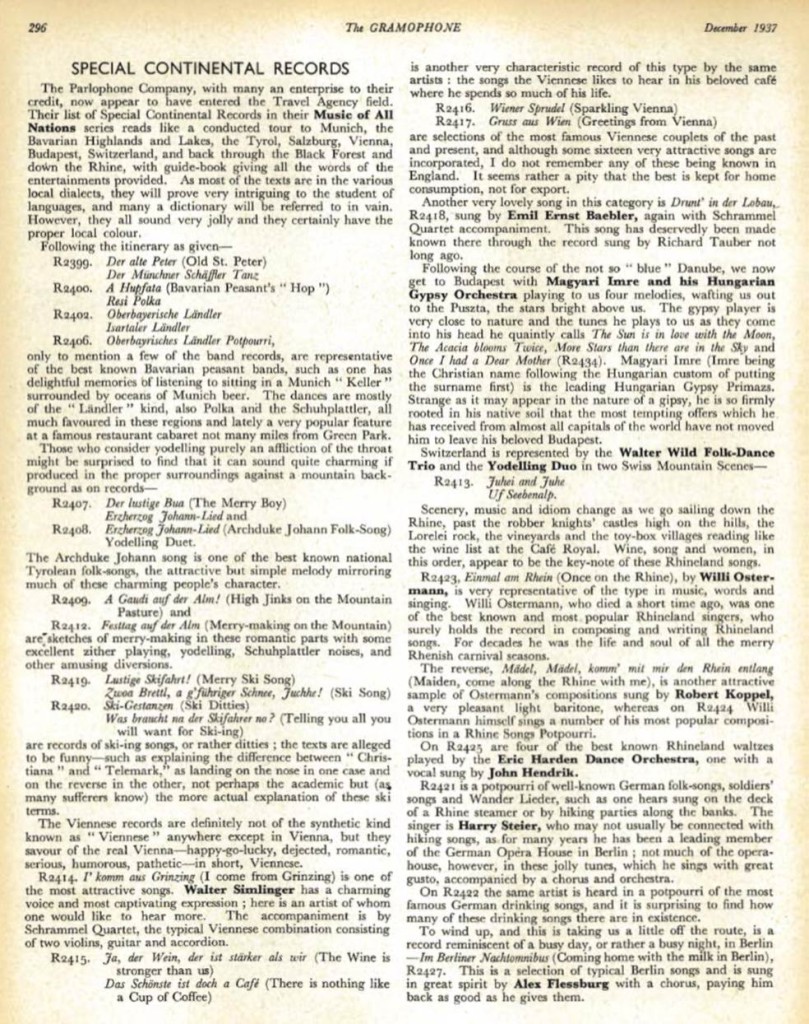

As part of an ongoing study of attempts within the Anglophone critical establishment to understand, curate, evaluate and otherwise ‘master’ the musics of other cultures during the twentieth century, I presented a paper at the IASPM Conference in Gijón in June 2013. The first part of the paper dealt with the critical reception of European records in Britain as represented in the pages of The Gramophone, the British magazine founded in 1923 to foster the discussion and evaluation of phonographic players and recordings. In addition to the representation of foreignness, I wanted to highlight the faith shown by many reviewers in the recordings to deliver, as if unmediated, the authenticity of otherness.

In addition to the somewhat paternalistic (arguably colonialist) tone, these early reviews were notable for their assertion of expertise and the construction of a relationship of trust between critic and potential consumers, something which has remained very much at the fore of subsequent critical discourse around music. While the body of potential critics may be broader and more diverse in our own era, the basic rhetorical strategies remain very similar. Reading pieces on foreign musics in these periodicals allows us to witness the formation and evolution of a receptive practice aimed at selecting and evaluating the new products of the culture industry, a practice that, from the outset, sought connections between product and place, text and context, representation and authenticity.

The discourse built around ‘foreign’ musics during the period before the Second World War can be seen as a forerunner of later periods of interest in international recordings, such as the Anglophone fascination with ‘exotica’ during the 1950s and 1960s and the ‘world music’ boom of the 1980s. While these later periods would accompany greater consumer access to foreign sounds, the pre-War period is notable for the reliance on ‘experts’ to mediate the sound of otherness to a relatively small and privileged audience. The period thus forms a link between what can be broadly thought of as a colonial era and an era of globalization.

In the second part of my Gijón paper, I turned to the recent reissue of many early international recordings by labels such as Honest Jons, Dust to Digital, Yazoo and Tompkins Square. The name of the label Dust to Digital gives a good summary of what these labels are doing: taking previously scarce recordings that were in danger of disappearing and remastering, digitising or otherwise polishing them to market to curious consumers. Such projects exist in many countries around the world, though I am focussing in my research on Anglo-American labels, looking also at more recent enterprises such as Soundway, Sublime Frequencies and Mississippi Records. What is of additional interest in the recent turn towards vinyl archeology is that we are now dealing with a temporal remove as much as a spatial one.

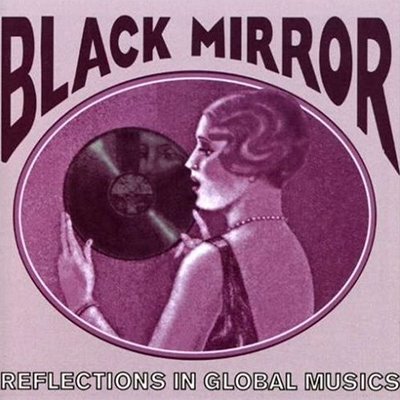

One of the many fascinating collections curated by Ian Nagoski bears the evocative title Black Mirror: Reflections in Global Musics. I find Nagoski’s metaphor of the record as a ‘black mirror’ very suggestive. On one hand, it refers to the way in which shellac records were used to reflect the world in the era of 78s. But, as Nagoski makes clear, it also highlights the way in which we go to historical artefacts to reflect back contemporary desires (Nagoski 2007). Like the photograph, the black mirror is a bounded space, allowing only a partial representation. Who or what the mirror reflects – whose desires, whose identity, whose imagined wholeness – are questions I am attempting to address in my work.

One of the many fascinating collections curated by Ian Nagoski bears the evocative title Black Mirror: Reflections in Global Musics. I find Nagoski’s metaphor of the record as a ‘black mirror’ very suggestive. On one hand, it refers to the way in which shellac records were used to reflect the world in the era of 78s. But, as Nagoski makes clear, it also highlights the way in which we go to historical artefacts to reflect back contemporary desires (Nagoski 2007). Like the photograph, the black mirror is a bounded space, allowing only a partial representation. Who or what the mirror reflects – whose desires, whose identity, whose imagined wholeness – are questions I am attempting to address in my work.

I am interested in the extent to which contemporary record labels and vinyl archaeologists attempt to explain the music they are reissuing. Some like to provide a wealth of context, providing expert opinion on musical styles, musicians and the historical, social and cultural contexts of the recordings. Others, such as the Honest Jons collection Sprigs of Time, prefer to offer collections ‘unburdened of musicology’. The end result is that consumers of these new collections are presented with sonic materials from the past with greater or lesser elements of mystery attached to them.

It was the idea of the first Managing Director of the Gramophone Company, William Barry Owen, to archive a copy of every record it issued … . By the time the company merged with Columbia in 1931, to form Electric & Musical Industries (EMI), the collection was already housed in Hayes, Middlesex, where it continues to accumulate. Unburdened of musicology, our album offers the merest glimpse of its miracles — hopefully with some giddy sense of its reach and range, and a sprinkling of the wonderment described in his memoirs by [Frederick] Gaisberg, recalling his Russian visits: ‘Another and totally strange world of music and people was opened up to me. I was like a drug addict now, ever longing hungrily for newer and stranger fields of travel.

(liner notes to Sprigs of Time)

The idea implied in Sprigs of Time is that such music can somehow be presented in an unmediated manner when shorn of the veridically demanding burden of musicology. But is this a fantasy that masks a deeper desire to connect with the mysteries of the world via a detour through the othering processes of time and space?

Is it the case that, whatever it is we go in search of when listening to the world, we are ultimately presented with an image of our own desire? The black mirror may only reflect back what we want to see, our imagination of otherness coloured by the remoteness of other times and places. Listening to records, it might be said, is always-already a nostalgic act in which desire becomes doubled. Nostalgia, as Susan Stewart puts it, is ‘the desire for desire’ (Stewart 1993: 23).

Brandon LaBelle, drawing upon the work of Mark M. Smith, observes that historical accounts of sonic experience from eras preceding recorded sound are as worthwhile as later ones due to the fact that such experience can be found in written form. The issue, suggests LaBelle, ‘becomes not so much to seek to the original sound, in pure form, but to hear it within history, through an extended ear, as a significant phenomenon, material, and shared experience participating in the movements of history.’ (LaBelle 2010: 108).

This is undoubtedly the case. However, that does not mean we should ignore the interesting questions raised by the seeming possibility to hear the past in recordings. But what is it that we are hearing?

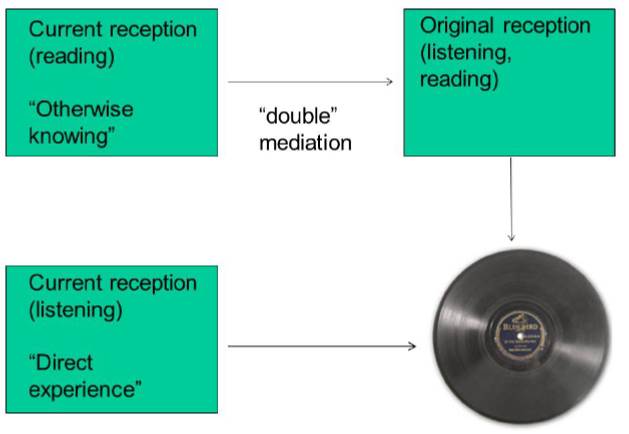

Photographs and phonographic records may have many similar qualities (Keightley and Pickering 2006) but we can never overcome the primary difference between them: the former is mediated visually and the latter sonically. There is a similar difference between listening to a sound recording and reading an account of a sound recording. With such differences in mind, we might think of a ‘reception matrix’ that would represent, at a simple level, the manner and directions in which we come to know the sonic past. Such a matrix would begin not with the original performance but with the current moment of reception, which may be an act of listening or reading. We could split these current acts into the two categories of “hearing” and “otherwise knowing”, the former referring to the act of listening to an original recording and the latter denoting a process of doubled mediation, such as the reading, viewing or hearing of another’s account of listening to an original recording. Such intervened mediation clearly references the fact that we can be witness to an earlier act of reception which itself points towards an originary moment.

Current hearing, then, seems more direct to us in that it follows a single course to the original object, whereas otherwise knowing requires a detour through the hearing of others. Yet, as suggested by the reissue programmes mentioned above, such direct experience is illusory, due not only to the potential deterioration of the original recording over time but also to any subsequent cleaning up and remastering of the recording and the rapid evolution of playback equipment.

The concept of the matrix seems an apt one for discussing phonographic recordings, given that one of the definitions of the word “matrix” is a mould used for the reproduction of disc recordings. Such usage signals the production process and the creation of the original object (an original that, in the era of mechanical reproduction, may not be that original after all). But the suggestion offered here is that that moment of production, of forming and moulding, can actually be said to take place not in the pressing factory but in the body of the listener. The matrix, like the mirror and the museum, produces meaning in the here and now, presenting us to the past even as it gives the illusion of presenting the past to us.

To a certain extent, recorded sound forces these questions by allowing the constant relocation and renegotiation of sound itself. We don’t have to fix accounts of past music in the past, for we can revisit recorded music, or visit it anew. The ‘black mirror’, meanwhile, is one that always reflects back on us where we are now. Like the book, it asks and answers contemporary questions. It also offers contemporary reassurances and allows an imagined sense of completeness, of ourselves in control, experts possessed of a certain mastery over the past. Indeed, recorded sound invites us to endlessly master and remaster the sonic past.

[Adapted from script of paper presented at the 17th Biennial IASPM Conference, Universidad de Oviedo, Gijón, Spain, 27th June 2013. Full script here.]

References

Keightley, E. and Pickering, M. (2006). ‘For the Record: Popular Music and Photography as Technologies of Memory’. European Journal of Cultural Studies 9/2: 149-65.

LaBelle, B. (2010). Acoustic Territories: Sound Culture and Everyday Life. New York: Continuum.

Nagoski, I. (2007). Liner notes to Black Mirror: Reflections in Global Musics (1918-1955). CD. Dust-to-Digital, DT-10.

Stewart, S. (1993). On Longing: Narratives of the Miniature, the Gigantic, the Souvenir, the Collection. Durham: Duke University Press.

Share this:

Category Research | Tags: archives, critical reception, history, listening, otherness, phonography, records, sound recordings, vinyl archaeology

[…] new Musical Materialities website: Richard Elliott’s wonderful illustrated essay “Phonographic Voices,” part of “an ongoing study of attempts within the Anglophone critical establishment to […]