Bacurau (Kleber Mendonça Filho and Juliano Dornelles 2019) : A Socio-Political Background to Cinematic Catharsis

Hello dear Mediático readers. How are you all? Are you staying in? We hope you are and that you can continue to do so. We offer moral support here at Mediático and we wish all our readers the best during these Covid-19 times. We support you if you are (like some of us) unable to take your eyes off rolling news or newsfeeds on social media in case you miss a vital piece of information that will keep you and your loved ones safe. Or whether you are (also like some of us) just coping with partners, multiple kids and pets not used to being shut in together so much. We also support you if you’re one of those able to throw yourself into work and find refuge in it. Some of you may just be able to take one viewing and reading suggestion a week that nevertheless brings you together with your community of scholars with whom you are not sharing those conference papers (and drinks) as you thought you would be at this time. And it is in this spirit of support and community that we bring you the following introduction to the winner of the Jury Prize at the Cannes Film Festival 2019 Bacurau ( Kleber Mendonça Filho) by regular and pretty fabulous contributor Natália Pinazza lecturer in Portuguese at the University of Exeter. Follow her @DrNPinazza

Bacurau is a film for Covid-19 times because it speaks to the strength of a community acting together against an outside force trying to destroy it. It’s also a great film to focus on today at Mediático because it dropped on mubi.com as many of us were beginning our self-isolation, and this is another good reason to put up this review right now.

Dr Pinazza’s post gives an excellent introduction to Bacarau providing some background to the film that explains why the villagers of Bacarau have been targeted in the near future world the film depicts, a world which nevertheless speaks to Brazil’s current political context.

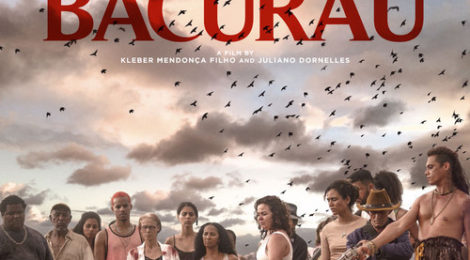

Bacurau (Kleber Mendonça Filho & Juliano Dornelles 2019) : A Socio-Political Background to a Cinematic Catharsis

by Dr Natália Pinazza

This post aims to provide an overview of some key socio-historical and cultural issues raised by Bacurau without giving away spoilers. Bacurau is a Brazilian film by Kleber Mendonça Filho and Juliano Dornelles that made waves after winning The Jury Prize at Cannes Festival in 2019. Bacurau has received international acclaim and has been reviewed by a number of newspapers and magazines across the globe, including The New York Times, The Guardian, Variety, and Le Monde.

The film also features an international cast, which includes German actor Udo Kier, French-American Alli Willow, and a few other American actors. Although Bacurau dialogues with internationally recognised genres, including the western and science fiction film, it delivers a very localized searing critique of Brazil’s current political climate, in particular, of the government of Brazil’s far-right President Jair Bolsonaro.

This post aims to provide an overview of some key socio-historical and cultural issues raised by Bacurau without giving away spoilers. Bacurau is a Brazilian film by Kleber Mendonça Filho and Juliano Dornelles that made waves after winning The Jury Prize at Cannes Festival in 2019. Bacurau has received international acclaim and has been reviewed by a number of newspapers and magazines across the globe, including The New York Times, The Guardian, Variety, and Le Monde.

Firstly, the title of the film, Bacurau, is also the fictitious name of a town set deep in the Sertão, which is a sort of outback or backlands located in the Northeast of Brazil, more precisely in the State of Pernambuco. The region of the northeastern backlands has been historically characterised by long periods of drought, which explains why distribution of water is an issue addressed in the film.

Because it is a region of historical political neglect and social marginalisation, the sertão became a place of resistance, and, for this reason, it has been a recurring location in Brazilian culture, including cinema. Films set in the sertão include the landmark film of the Cinema Novo movement in the 60s, Black God, White Devil (Glauber Rocha 1964), as well as more recent films, such as Central Station (Walter Salles 1998), which was nominated for the Oscar for the best foreign-language film in 1998. Therefore, Bacurau’s setting (the sertão/backlands) is culturally significant and functions as a reference to a Brazilian cinematic tradition.

Because regionalism is an important factor in the film, there are several historical and cultural references to the Northeast region. There is also the museum, which highlights moments of northeastern history and culture, including Cangaço, which was a phenomenon of banditry in Northeast Brazil in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Significantly, the film includes multiple close-ups of images of Cangaceiros, northeastern bandits who wore half-moon shaped hats, housed in its town museum.

The national division between the sertão in Pernambuco and the Southern states of São Paulo and Rio de Janeiro is central to the film. Two Brazilian characters from the South with a key role present themselves as foreigners even though they are Brazilians. In doing so, the film satirises the tendency of Southern Brazilians to claim that they have European origins to differentiate themselves from the rest of Brazil. The film depicts southern Brazilians as villains who turn against other Brazilians to defend foreign interests.

This divide between north and South has recently been aggravated by derogatory comments made by Brazil’s president Jair Bolsonaro, who encourages anti-northeastern sentiment because that is the region that supports the opposition, that is, the Worker’s Party. Significantly, the town of Bacurau is inhabited by prostitutes, artists, and members of the LGBT community, communities which have been recently under attack by Bolsonaro’s homophobic rhetoric. In the film, São Paulo is portrayed as the locus of oppression as characters watch public executions on TV taking place in the city.

Therefore, Bacurau centres on marginalised identities inhabiting the marginalised region of the Sertão, which is often deemed as backward. uncivilized and primitive. Through Bacurau’s disappearance from the map, the film denounces political negligence, oppression, and contempt. Even though the film is set in the future, Bacuarau’s narrative charts how the surviving rebels and so-called misfits of Brazil resist external threats to its community, culture, and history.

The film’s depiction of politicians and their relationship with the population are marked by lies, deceit, and corruption, which evoke a shared sense of frustration with audiences. Although the critique resonates deeply with localised readings of the film, international audiences can quickly identify with the generalised frustration at politicians. Despite its political and violent threat, Bacurau signals at resistance and functions as a sort of cinematic catharsis for Brazilian people in desperate political times.