Phonographic Voices (ii)

0June 24, 2014 by Richard Elliott

In her book In Search of the Blues, Marybeth Hamilton highlights a contradiction at the heart of writings about the Delta blues. Although the music is known primarily through recordings, those who have valorised it have tended to either downplay or explicitly negate the mediating effects of technology.

Blues enthusiasts, in the main, have ignored those technological trappings, the phonograph, the disc, the electrical current; only the voices remain, fierce and immediate … What makes the Delta blues singular, and paradoxical, is its magical capacity to transcend that technology, to be conveyed mechanically and yet be perceived as pristinely untouched by the modern world.

(Hamilton 2007: 9)

There is also the recurring issue of ‘experts’, be they collectors, folklorists or critics: ‘In an age of mechanical reproduction, they set themselves up as cultural arbiters, connoisseurs whose authority rested on their powers of discernment, their ability to distinguish the ersatz from the real.’ (Hamilton 2007: 10) This is an issue I have addressed in the closing chapter of my book on fado, where I noted the role of the critic/expert as both informant and authenticator (Elliott 2010); it is also an area I am exploring in ongoing work on discourses surrounding ‘foreign’ musics of the past.

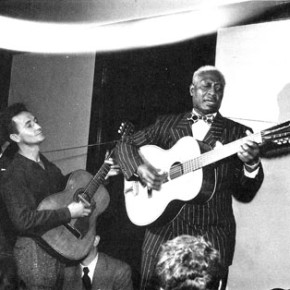

Hamilton summarises the desire of collectors such as Alan Lomax as follows:

how do you capture the real black voice in the age of mechanical reproduction? Answering that question meant engaging with the very technology whose impact they feared, ferreting out singers with portable phonographs and, eventually, rifling through bins in used-record stores, searching for voices that sounded archaic, willing themselves to hear past the machine.

(Hamilton, p. 10)

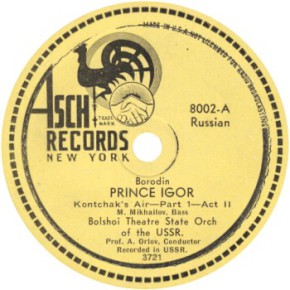

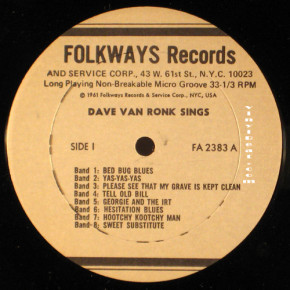

Greg Milner claims that Lomax ‘wanted authenticity, but he was not above engineering it’ (Milner 2009: 98). In contrast, Moses Asch, founder of the Folkways label, insisted on sticking to one microphone and trying to capture the sound in as unmediated a manner as possible, thus ‘simplifying the effects of historical memory’. However, the studio process entailed a fencing-off as distorting as anything perpetrated by the Lomaxes in the field. ‘The studio was sacred for Asch. It shut out all parts of the outside world – symbolized by the invisible hand of the marketplace, changing the context as surely as John [Lomax] did when he made trapped convicts sound like they were free outdoors – and allowed in only “the music”‘ (Milner 2009: 98).

Asch’s first (self-titled) record label began by recording Jewish cantors, a move that mirrors Harry Smith’s move from compiling the Anthology of American Folk Music to recording Jewish liturgical music (Smith produced 15 albums’ worth of material, two of which were released by Folkways). One of Asch’s prinicple artists, Cantor Liebele Waldman, was influenced by Cantor Rosenblatt, who had recorded in the 1920s. Yiddish language music was seen in that period as a market similar to hillbilly and race records, though interest died away during the Depression.

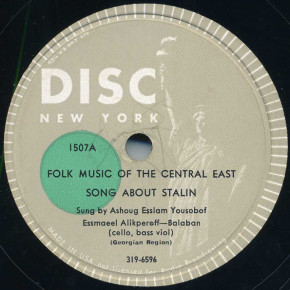

Asch moved from these Jewish sides to recording Lead Belly, then Wallace House’s Folk Songs of the United Nations , then on to Burl Ives. Asch’s second label Disc focussed on jazz and folk. Folk, as Peter Goldsmith points out, was categorised as ‘music deliberately lacking in commercial pretensions’ (Goldsmith 1998: 175) and was now seen as political for this reason above and beyond any explicit messages that might be conveyed by the lyrics. Woody Guthrie used his releases of the time to rail against commercial music in a manner comparable to Theodor Adorno:

Hollywood songs don’t last. Broadway songs are sprayed with a hundred thousand dollars to get them going, and they last … A few months at most. The Monopoly on Music pays a few pet writers to go screwy trying to write and re-write the same old notes under the same old formulas and the same old patterns. Every band on the radio sounds exactly alike … Hitler declared war on the world and several million good people walked into their graves to keep the world a Union World, but do the gals and the bands play or sing a single note about it?

(Woody Guthrie, liner notes to Folksay (Asch 432, 1944), quoted in Goldsmith 1998: 147)

This folk/commercial divide would be an ongoing issue for Asch through various colourations of the debate in different contexts. But, as Goldsmith points out, the commercial success of a few of Asch’s jazz recordings helped to finance his more esoteric work (177). As for his role in mediating the “authentic” music of others, Asch said of Woody Guthrie: ‘He was using me like a pen, to make a book. I was working the machinery, but he was using it for himself’ (quoted in Bluestein 1987: 302). Guthrie would use the recording process to work out the best version for a new song, meaning that the medium of recording became a vital tool in the construction of his work and adding a mediating level that more romantic accounts of his performance practice (his own included) tend to neglect.

References

Bluestein, G. (1987). ‘Moses Asch, Documentor’. American Music , Vol. 5, No. 3: 291-304.

Elliott, R. (2010). Fado and the Place of Longing: Loss, Memory and the City. Farnham: Ashgate.

Goldsmith, P.D. (1998). Making People’s Music: Moe Asch and Folkways Records. Washington: Smithsonian Institution Press.

Hamilton, M. (2007). In Search of the Blues: Black Voices, White Visions. London: Jonathan Cape.

Milner, G. (2009). Perfecting Sound Forever: The Story of Recorded Music. London: Granta.

Category Research | Tags: agency, Alan Lomax, Blues, collecting, ethnomusicology, Folk, Folkways, Jazz, Moses Asch, phonography

Leave a Reply