The politics of listening and the fantasy of total control

1April 8, 2014 by Richard Elliott

Collecting and archiving are processes that help connect the notions of ‘recording loss’ and ‘lost recordings’, both of which hinge upon the sense of anxiety brought about by loss. Evan Eisenberg (1988: 14-16) provides a ‘tentative list’ of five reasons for collecting:

- The need to make beauty and pleasure permanent

- The need to comprehend beauty

- The need to distinguish oneself as a consumer

- The need to belong

- The need to impress others, or oneself.

Other writers have focussed on the identification of record collecting and masculinity, no doubt inspired by the kind of ‘common sense’ connection between men and record collecting chronicled so successfully in Nick Hornby’s novel High Fidelity (1995) and in its film adaptation. Simon Reynolds manages a more nuanced response in an essay that deals with masculinity, collecting and the anxiety of loss. Reynolds suggests: ‘If there’s a distinctively masculine “sickness” [in record collecting,] it’s perhaps related to the impulse to control, contain, master what actually masters, ravishes, disorganizes you: to erect bulwarks against the loss of self that is music’s greatest gift’ (Reynolds 2004: 294). But he quickly adds, ‘Or is it the other way around: collecting as a perverse consumerism, a literally consuming passion that eats up your life?’ Reynolds speaks also of collecting as a parallel life, not an alternative self-contained life: ‘On the one side, the life of loves lost and kept, family tribulations, “civilian” friendships; on the other, the world of music’ (295).

Eisenberg, meanwhile, speaks of ‘heroes of consumption’ such as his friend Clarence, a truly obsessive record collector: ‘The true hero of consumption is a rebel of consumption. By taking acquisition to an ascetic extreme he repudiates it, and so transplants himself to an older and nobler world’ (Eisenberg 1988: 15) This world is one that, for many, is sealed into the very grooves of the discs. There is a fragility here that always threatens to fragment the memory, a realisation that the musical vehicle – be it record, CD or hard drive – might be little more permanent than the air upon which sound drifts away.

Eisenberg, meanwhile, speaks of ‘heroes of consumption’ such as his friend Clarence, a truly obsessive record collector: ‘The true hero of consumption is a rebel of consumption. By taking acquisition to an ascetic extreme he repudiates it, and so transplants himself to an older and nobler world’ (Eisenberg 1988: 15) This world is one that, for many, is sealed into the very grooves of the discs. There is a fragility here that always threatens to fragment the memory, a realisation that the musical vehicle – be it record, CD or hard drive – might be little more permanent than the air upon which sound drifts away.

For Geoffrey O’Brien, writing about 78s, the fragility of the object is connected to the fleetingness of the lost moment:

The disks themselves – at once heavy and fragile with an extra layer of surface noise – suggest a past surviving against heavy odds. It must be given special attention because its traces – carved into those thick grooves and extracted from them with a thick obsolete needle as crude as a barnyard nail – are so easily smashed. The past is retrieved, but just barely, and it is forever in danger of being smashed beyond recapturing: I learned that the day ‘The Viper’s Drag’ slipped from between my fingers.

(O’Brien 2004: 54-55.)

These vessels, then, must be treated with the utmost respect. This includes the manner in which the collection is organised, as Walter Benjamin makes clear in his essay ‘Unpacking My Library’ and Georges Perec in his ‘Brief Notes on the Art and Manner of Arranging One’s Books’. This process sheds further light on the project of collecting inasmuch as the latter is an impossible quest for some kind of totalisation of knowledge. Perec writes:

Like the librarians of Babel in Borges’s story, who are looking for the book that will provide them with the key to all the others, we oscillate between the illusion of perfection and the vertigo of the unattainable. In the name of completeness, we would like to believe that a unique order exists that would enable us to accede to knowledge all in one go; in the name of the unattainable, we would like to think that order and disorder are in fact the same word, denoting pure chance.

(Perec 1999: 155)

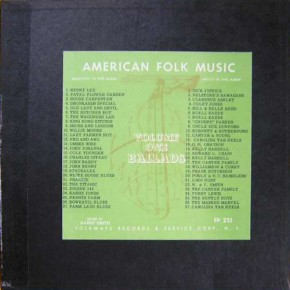

It is interesting to compare this view to that of Harry Smith, a figure central to this project and arguably a key figure for any contemporary attempt to think of the relationships between ritual, remembrance and recorded sound. Smith, best known to vernacular music fans for having compiled the 1952 Anthology of American Folk Music, was an inveterate collector of all kinds of objects. Collecting, for Smith, was an attempt to find connections and correspondences between the disparate elements of the universe; his understanding of these connections was guided as much by structural anthrolopology and linguistics as by an obsession with alchemy, the occult and the history of esoteric thought. In an interview with John Cohen in 1969, Smith described his collecting practices as follows:

It is interesting to compare this view to that of Harry Smith, a figure central to this project and arguably a key figure for any contemporary attempt to think of the relationships between ritual, remembrance and recorded sound. Smith, best known to vernacular music fans for having compiled the 1952 Anthology of American Folk Music, was an inveterate collector of all kinds of objects. Collecting, for Smith, was an attempt to find connections and correspondences between the disparate elements of the universe; his understanding of these connections was guided as much by structural anthrolopology and linguistics as by an obsession with alchemy, the occult and the history of esoteric thought. In an interview with John Cohen in 1969, Smith described his collecting practices as follows:

It has something to do the desire to communicate in some way, the collection of objects. Now I like to have something around that has a lot of information in it, and since then, it seems to me that books are an especially bad way of recording information…So I’ve been interested in other things that gave a heightened experience in relation to the environment…

…the type of thinking that I applied to records, I still apply to other things, like Seminole patchwork or to Ukrainian easter eggs. The whole purpose is to have some kind of series of things. Information as drawing and graphic designs can be located more quickly than it can be in books. The fact that I have all the Seminole designs permits anything that falls into the canon of that technological procedure to be found there. It’s like flipping quickly through. It’a a way of programming the mind, like a punch card of a sort…(Quoted in Perchuk and Singh 2010: 7)

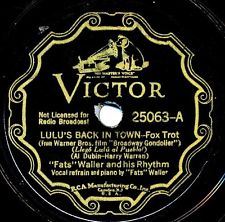

The existence of the collection, however, means that the past can be brought home. Nostalgia can be satisfied by a simple mechanical operation, as O’Brien notes: ‘But whatever might be lost or broken or forgotten is nothing compared to the miraculous rebirth that occurs every time the needle hits the groove. Here is Fats Waller himself, not dead but present, so present that he overwhelms the well-ordered precincts of the living room. The sound sprawls. What vibrates here has more life than any room. In ecstasy Fats slams the keys to lay down the unending groove of “Lulu’s Back in Town.”’ (O’Brien: 55.) As Evan Eisenberg’s friend Clarence put it, ‘records are inanimate until you put the needle in the groove, and then they come to life’. (Eisenberg 1988: 28; see also Middleton 2006).

The existence of the collection, however, means that the past can be brought home. Nostalgia can be satisfied by a simple mechanical operation, as O’Brien notes: ‘But whatever might be lost or broken or forgotten is nothing compared to the miraculous rebirth that occurs every time the needle hits the groove. Here is Fats Waller himself, not dead but present, so present that he overwhelms the well-ordered precincts of the living room. The sound sprawls. What vibrates here has more life than any room. In ecstasy Fats slams the keys to lay down the unending groove of “Lulu’s Back in Town.”’ (O’Brien: 55.) As Evan Eisenberg’s friend Clarence put it, ‘records are inanimate until you put the needle in the groove, and then they come to life’. (Eisenberg 1988: 28; see also Middleton 2006).

It is not only recordings that promote anxiety even as they bring comfort. Accompanying the move to sound recording is the loss of sight of musical instruments (although see Eisenberg’s discussion of the phonograph as instrument in Chapter Ten of The Recording Angel) and the shrinking of recording and playback devices. The iPod generated a notable level of distrust due to its lack of objects (no records or other discs, cases, etc.), a distrust partly addressed by the attachment of numerous accessories to the player itself, such as cases, speakers, ‘skins’, etc.

With the development of telephony and phonography came an uncanniness brought about by not seeing the source of the sound, a feeling highlighted by Proust in his description of the sound of the voice on the telephone in A la recherche du temps perdu. With the current methods of accessing music, where the only object involved might be a computer, iPod or other mobile device, this process has intensified, as Julian Dibbell discussed in ‘Unpacking Our Hard Drives’, an update of Benjamin’s essay on libraries. Dibbell asked: ‘Can the erotics of pop consumption […] survive when records live unseen and untouched on our hard drives, and if so, how? Where is the love in the age of the download?’ (Dibbell 2004: 280) Or, we might add, updating Dibbell’s references, in the age of the stream.

It is worth noting here the appeal to sight and touch, reminding us that there is more to music than listening. Dibbell quotes Benjamin on mourning the collector but suggests that the ‘eros’ – better understood as a kind of obsession – has not gone away but has transmuted into different but comparable practices related to downloading and sharing music, such as the ‘zero day’ scene (involving the downloading of music before it has been officially released) which thrives on the obsession to be first (found also in internet forum threads), to have the music before anyone else and on the thrill of illegality. Though many have cautioned against the utopian narratives of consumer control that the internet suggested, Dibbell is correct to focus on the thrill of the process. What remains constant is the obsession based around the extra Thing, the part of music which is not music itself but which represents desire: the record, the MP3, the autograph.

If something scares us in the prospect of losing ourselves in music, then it may well be that this anxiety is only increased by the ‘disappearance’ of the music itself into the electronic labyrinths of computer hard drives. This could be one reason for the persistent veneration of the listening ritual, a process often held dear by those most vociferously opposed to new media such as iPods and smart phones. What is for these critics an ‘agency of listening’, a refusal of random elements, can be seen as a result of an anxiety around sound’s authority and around one’s ‘incipient obedience’.

Listening becomes an act of mastery, often gendered as a masculine reclamation of feminine space, connecting it to the male mastery of ‘feminine’ consumption that some see record collecting as being. Agency here means imposing order on a seemingly chaotic world (a world of computer-generated and -maintained favourites and wishlists, of shuffle functions on iPods or random modes on CD players). The existential question relating to this agency becomes ‘To shuffle or not to shuffle?’ (to stream or not to stream?). The implicit suggestion in critical responses to such questions is that other (non-critical) people do not listen properly.

Listening becomes an act of mastery, often gendered as a masculine reclamation of feminine space, connecting it to the male mastery of ‘feminine’ consumption that some see record collecting as being. Agency here means imposing order on a seemingly chaotic world (a world of computer-generated and -maintained favourites and wishlists, of shuffle functions on iPods or random modes on CD players). The existential question relating to this agency becomes ‘To shuffle or not to shuffle?’ (to stream or not to stream?). The implicit suggestion in critical responses to such questions is that other (non-critical) people do not listen properly.

This is connected to authenticating accounts of popular music taste and cultural capital, as Anahid Kassabian points out in her work on ubiquitous music. I would suggest that the need to enact mastery over the listening experience (or process) exhibits another submission, to the anxiety of loss. And while the criticisms of new media are often essentially a performance of such anxiety, the counterpoised notion of the listening ritual does at least recognise that there is importance in the music, wants to show respect (fidelity), wants to make of each listening experience an event.

References

Dibbell, J. (2004). ‘Unpacking Our Hard Drives: Discophilia in the Age of Digital Reproduction’, in Eric Weisbard (ed.), This is Pop: In Search of the Elusive at Experience Music Project. Cambridge: Harvard University Press: 279-288.

Eisenberg, E. (1988). The Recording Angel: Music, Records and Culture from Aristotle to Zappa. London: Picador.

Middleton, R. (2006). ‘“Last Night a DJ Saved My Life”: Avians, Cyborgs and Siren Bodies in the Era of Phonographic Technology’, Radical Musicology 1: 31 pars. http://www.radical-musicology.org.uk.

O’Brien, G. (2004). Sonata for Jukebox: Pop Music, Memory, and the Imagined Life. New York: Counterpoint.

Perchuk, A. and Singh, R. (eds) (2010). Harry Smith: The Avant-Garde in the American Vernacular. Los Angeles: Getty Research Institute.

Perec, G. (1999). Species of Spaces and Other Pieces. Rev. edn., ed. & tr. John Sturrock. London: Penguin.

Reynolds, S. (2004). ‘Lost in Music: Obsessive Record Collecting’, in E. Weisbard (ed.), This is Pop: In Search of the Elusive at Experience Music Project. Cambridge: Harvard University Press: 289-307.

Share this:

Category Research | Tags: agency, collecting, consumption, listening, materiality, sound recordings

[…] The politics of listening and the fantasy of total control […]