Special Dossier on Roma: Children of Women? Alfonso Cuarón’s love letter to his nana

by Deborah Shaw*

Roma the latest film by Alfonso Cuarón has attracted much media attention for many reasons: it has already won a number of international awards and looks set to win many more; it has showcased the Netflix production and distribution model proving that cinemagenic films can flourish with simultaneous and near simultaneous streaming and theatrical releases; it has shown that a Spanish (and Mixteco) language art film can reach global audiences; and, most importantly, and the focus of this short essay, it has placed an indigenous woman centre-stage and highlighted the value of her story.

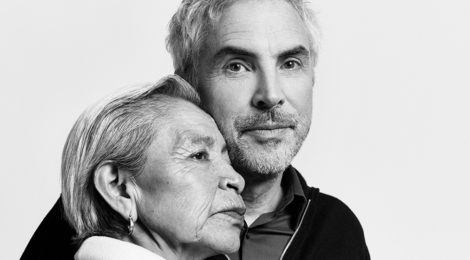

As is now well documented, Roma’s central character Cleo is based on Cuarón’s nanny Libo (Liboria Rodríguez). She is played beautifully by Yalitza Aparicio, a non-professional actor and recently qualified schoolteacher. Adult Cuarón has maintained close relations with Libo, to whom he dedicates Roma. She made an appearance in Y tu mamá también playing Tenoch’s (Diego Luna) family housekeeper, Leodegaria (Leo), as Cuarón reveals in an interview with Fernanda Solórzano. Yet, in the earlier film the wandering camera’s focus on Libo and other usually marginalised Mexicans, always returns to the protagonists, the Euro-Mexican upper-middle-class Tenoch and his lower-middle-class friend Julio (Gael García Bernal).

In Roma, the camera remains on Cleo and takes us to the spaces of her existence that her employer-family never see. In this way Cuarón calls to account a system, a class and a generation who have not known how to see Libo, Cleo and so many others in their position, or believe they have stories worth telling. Roma is the result of Cuarón’s acknowledgement that the lives that he and other middle-class Mexicans enjoy are built on the exploitation of poor indigenous or mestiza women. Oppression is naturalised by oppressors, and the labour of domestic servants is rendered invisible by those who believe that Mexico’s indigenous and mestizo class exist to serve them. Roma denaturalises this system and presents an anatomy of power relations between domestic workers and their employer-families.

The film is full of illustrations of unconscious power dynamics; a particularly telling moment for me comes when the youngest child hears Cleo talking on the phone in Mixteco, her mother tongue. He repeats disconcertedly, ‘What are you saying?’, and implores her to ‘stop talking like that’. Here we see an entirely unconscious attempt to deny Cleo an identity separate from the person the child needs her to be. She pushes back as much as she is able, sends the child on his way and continues talking.

The process of making the film is interesting in this regard as Cuarón, from the point of view of the present, remembers a childhood past he was unable to fully perceive or comprehend at the time. As he notes to Solórzano, ‘You can only see memories from the point of view of the present’ (my translation). Roma creates a film from the director’s memories presented through the filter of those Libo has communicated to him. In Cuarón’s chats with his ‘nana’ he has her reconstruct her daily routine in what he describes as almost forensic detail, and he realises all he never knew: her exercise routine, her room, her trips to the market, his grandmother’s prohibition on using electricity in her room (Solórzano, 2018). In other words, this is (admittedly his version) of Libo’s life outside of his childhood field of vision that he recuperates and re-enacts.

With Roma Cuarón makes amends; the family are the supporting actors to Cleo’s life, and she features in (almost) every shot. She never rests, never stops, and her labour is made visible throughout: she is housekeeper, cleaner, nanny to the children; she washes the clothes, runs errands, and cleans up dog shit. The only friendship she has, that we see, is with Adela, the other domestic employee who takes care of the cooking. Nonetheless, these imbalanced power dynamics are still relationships built on love and genuine emotion, creating what Shireen Ally refers to as a ‘dialectic of intimacy and distance’ (Ally 2015: 51), and which I analyse elsewhere in a chapter on domestic servants in Latin American films. So, when the children frequently tell Cleo they love her, and she tells them that she loves them back these moments powerfully convey a depth of love between the children and Cleo. Indeed, Roma is the product of this mutual love.

Yet, Cleo occupies a space both inside and outside the family. She is both maternal figure and domestic worker. Any intimate family moments are interrupted when she has to attend to her family-employer’s needs. This is a solid power dynamic cultivated over centuries and rooted in colonial hierarchies of power. Even extreme emotional disruptions occasioned for instance when Cleo loses her baby, or when she saves the lives of the two youngest children in a near drowning incident, cannot alter the server/served paradigm. She is thanked for saving their lives, but immediately dispatched to bring the children smoothies.

Cleo’s child is stillborn, and the baby’s death and her confession that she didn’t want her, perhaps symbolize the fact that Cleo would not have been permitted to care for her own child. Sofía (Marina de Tavira) may appear to be supportive, securing medical help for a pregnant Cleo and promising not to fire her but she also calls her ‘mensa’ (dumb) and treats her like a child taking her by the hand at the hospital. Additionally, the doctor’s instructions for her to rest are ignored and one wonders what would have happened had her baby girl survived. She would most likely have been brought up in her home village by Cleo’s mother to ensure that she can serve her middle-class employer-family unencumbered.

Roma is then, a personal, biographical, but also political film that is as much about Mexico’s oppression of its indigenous women as it is about the life of the young filmmaker in the early 1970s. As I have written elsewhere, ‘an exploration into the servant/employer dynamic as treated in a group of films exploring this dynamic across Latin America, reveals the political heart of nations and deep structural inequalities’. A generation of filmmakers across Latin America have probed these inequalities and Cuarón’s film can be placed within a growing body of work that situates the figure of the domestic worker centre-stage.[1]

*Dr. Deborah Shaw is Reader in Film Studies at the University of Portsmouth. Her teaching focuses on Transnational Cinema and Gender, Sexuality and Cinema. Her research interests include transnational film theory, Latin American cinema, and film and migration, and she has published widely in these areas. She is the founding co-editor of the Routledge journal Transnational Cinemas, and her books include Contemporary Latin American Cinema: Ten Key Films (Continuum Publishers, 2003), The Three Amigos: The Transnational Filmmaking of Guillermo del Toro, Alejandro González Iñárritu, and Alfonso Cuarón, (Manchester University Press, 2013), The Transnational Fantasies of Guillermo del Toro, co-edited with Ann Davies and Dolores Tierney (Palgrave Macmillan, 2014), and Latin American Women Filmmakers: Production, Politics, Poetics, co-edited with Deborah Martin for the World Cinema Series with I.B.Tauris (2017). Deborah has written articles that have been published in The Conversation, The Independent, The New Zealand Herald, Newsweek, SBS, Pink News, Tranzgendr and The Huffington Post.

[1] Examples include Lucía Puenzo’s Argentinian film El niño pez/The Fish Child (2009) the Brazilian Maids/ Domésticas (Meirelles, Olival, 2001), Sebastián Silva’s Chilean film La nana/The Maid, Claudia Llosa’s Peruvian La teta asustada/The Milk of Sorrow (2009), Juan Carlos Valdivia’s Bolivian set Zona Sur/ Southern District (2009), Gabriel Mascaro’s Brazilian documentary Doméstica/Housemaids (2012), the Mexican Hilda (2014) by Andrés Clariond, Réimon (2014) by the Argentinean director Rodrigo Moreno and the Brazilian Que Horas Ela Volta/ The Second Mother (2015) by Anna Muylaert.