Falling into the Embrace of the Serpent by Deborah Shaw

Mediático is delighted to present a consideration of the much heralded Colombian film Embrace of the Serpent by Deborah Shaw, Reader in Film Studies at the University of Portsmouth. Her research interests include transnational film theory, and Latin American cinema, and she has published widely in these areas. She is the founding co-editor of the Routledge journal Transnational Cinemas, and her books include Contemporary Latin American Cinema: Ten Key Films (Continuum Publishers, 2003), The Three Amigos: The Transnational Filmmaking of Guillermo del Toro, Alejandro González Iñárritu, and Alfonso Cuarón (Manchester University Press, 2013), The Transnational Fantasies of Guillermo del Toro, co-edited with Ann Davies and Dolores Tierney (Palgrave Macmillan, 2014), and Latin American Women Filmmakers: Production, Politics, Poetics, co-edited with Deborah Martin for the World Cinema Series (forthcoming at I.B.Tauris).

Every so often a special film comes along and slaps us in the face and demands our attention. A film that reminds us why we became and remain academics, critics and teachers. We take on these roles because we love films that teach us about the world we live in, and because we want to share our enthusiasm and that knowledge. Learning and sharing knowledge is one of the central themes of Embrace of the Serpent. It is an award-winning film, securing Colombia’s first Oscar nomination, for director Ciro Guerra previously known for two films that were well received on the festival circuit: Wandering Shadows (2004) and The Wind Journeys (2009). Like Guerra’s previous films Embrace of the Serpent has been exhibited on the festival circuit, but it has also found its way on to global screens small and large.

Like so many recent films from Latin America, Embrace of the Serpent is an example of transnational filmmaking. Some usual suspects feature among its funders, including the Dutch Hubert Bals Fund, Ibermedia, the Argentine National Film Institute INCAA, Argentine production companies, the Colombian Caracol Televisión and the Venezuelan Nortesur Producciones. It also highlights encounters between peoples from diverse nations (the colonisers and colonised and those who study them) and reveals the historical conflicts and tensions between them. Yet, it is deeply rooted in specific local communities (the tribes of the Colombian Amazonian jungle) and reveals their culture and concerns, and their untold stories.

Embrace of the Serpent is a film that is simple and beautiful, yet also epic, ecological, mystical, cosmic and extra-terrestrial. It presents us with a vision of how broken people can be made whole again. It is visually gorgeous, unusually shot on film in black-and-white by cinematographer David Gallegos. In addition to its visual splendour, it provides an example of the kind of ethical filmmaking which could teach some directors a thing or two. There are evident references (noted by critics such as Mark Kermode) to Werner Herzog’s Fizcarraldo (1982) and Francis Ford Coppola’s Apocalypse Now (1979). But, as Kermode also notes, Embrace of the Serpent presents a new vision of the encounter between colonisers/invaders and indigenous people, different from that seen in previous Euro/US centric films. Guerra reverses the colonial gaze and has his audience, along with his white protagonists, look and listen with new eyes and ears.

An initial examination of the film’s genesis would suggest a continuation of the focus on white colonisers/invaders. Part of the source material comes from the ethnographic journals of two real-life German and American explorer/scientists Theodor Koch-Grünberg and Richard Evans Schultes. In the film they transform into Theo(dor) von Martius (Jan Bijvoet) and Evan (Brionne Davis). The film places the white men in the Amazonian jungle in the region of Vaupés in Colombia in search of the sacred (fictional) yakruna plant known for its healing properties.

Their adventures form the focus of the intertwining parts of the narrative, with Theo’s tale set in 1909 and Evan’s set in 1940. Yet, their points of view do not guide the narrative. The director tells Michael Guillén for Cineaste:

As I started working with the Amazonian communities, I realized that their point of view regarding this story had never been told. That was the real film that I had to do because it’s the one film that hasn’t been done, that I have never seen, and that would make the film unique and special.

This point of view is provided by Karamakate, the proud shaman and survivor of the murderous Colombian rubber barons who have pushed his tribe (the Cohiuano) to the point of near extinction. Young Karamakate (Nilbio Torres) is the travel companion to Theo, and old Karamakate (Antonio Bolívar) to Evans. Guerra is sensitive to the representational politics of his film, the Cohiuano tribe is fictional, a realistic composite of other tribes put together by the director to avoid misrepresenting a specific tribe. He also counters the familiar colonialist trope of guide/native informant in the character of Karamakate. Rather than appear as a means to fulfill the destiny of the white man, young Karamakate has his own reasons for helping to cure and accompany Theo: the search for the remainder of his people. Old Karamakate is also motivated by his own destiny and by that of his people; he is searching for his identity, as he has through isolation become a chullachaqui, a hollow and empty being without memories. He hopes to recover his selfhood through the journey with the white man whom he sees as another incarnation of Theo.

The worldview of the Amazonian tribespeople is also seen in the mythic structure of the film. Guerra tells Michael Guillén that the title has its origins in Amazonian mythology:

extraterrestrial beings descended from the Milky Way, journeying to the earth on a gigantic anaconda snake. They landed in the ocean and traveled into the Amazon, stopping at communities where people existed, leaving these pilots behind who would explain to each community the rules of how to live on earth: how to harvest, fish, and hunt.

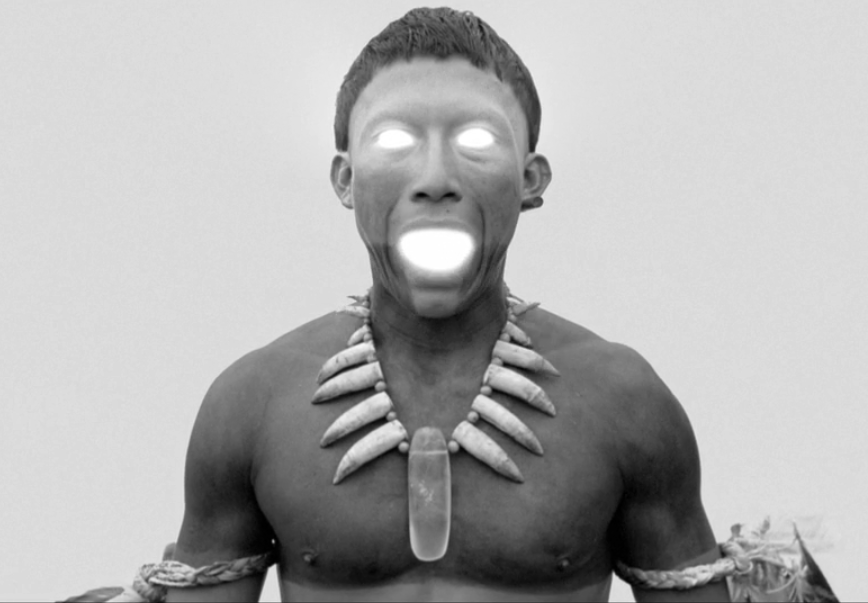

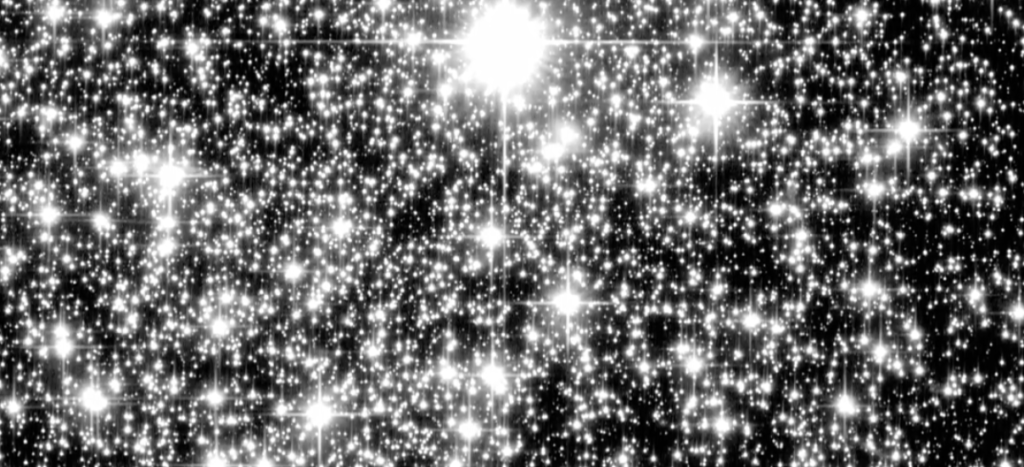

The film ends when Evans takes the yagé, a hallucinogenic drug made from the sacred plant for which he has been searching. He experiences a vision that transports him to a cosmic dimension, endowing him with a truth that his rational science filled culture cannot provide, and making him see the world anew. Here the imagery transports us from earthly beauty to cosmic wonder, as Evans sees through Karamakate‘s eyes.

Evans sees through Karamakate’s Eyes

From earthly beauty to cosmic wonder

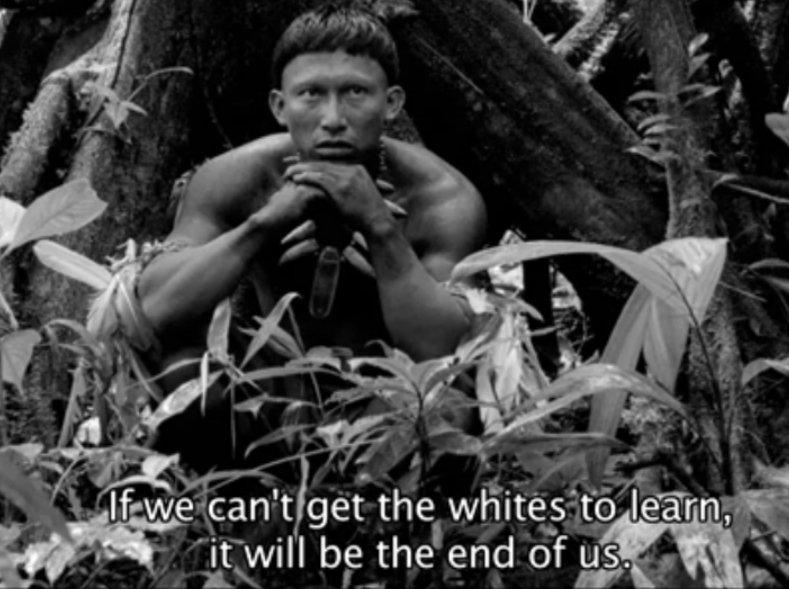

Manduca (Yauenkü Migue), Theo’s protector, provides the moral compass of the film and is also the reason why Karamakate agrees to help the white men. It is Maduca who teaches Karamakate that the key to the salvation of their tribes lies in teaching the whites about their culture. Manduca travels with Theo because he can help Theo acquire knowledge about his people that Theo will share through his published studies. In this, the colonial power system is strategically used by the tribespeople for their own survival. There is no superior white saviour here, only white men who must be humbled, corrected and taught how to see and recognize the flaws in their culture and the strengths in the culture of the Amazonian people. Over and again the film, rooted in historical facts, reverses colonial hierarchies and paints the culture of the white man as barbaric and uncivilized: from the rubber barons who enslave, whip, maim and murder indigenous workers; to the insane Messianic cult leader who makes of the tribespeople his worshipers; to the priest who has in the eyes of the church ‘saved’ young orphaned boys, but who whips them savagely, destroys their culture, and refuses to allow them to speak their own languages.

Karamakate learning Maduca’s lessons

Additional power is afforded to Embrace of the Serpent through the film’s afterlife. We learn that Antonio Bolívar Salvador who plays old Karamakate, one of the last of the Ocaina ‘helped rewrite the script and translated it into several languages’. The film was shown to Amazonian tribes people, who were pleased their story of exploitation and murder at the hands of the rubber barons and missionaries was told respectfully. In this respect, Guerra takes his place alongside the ethno-explorers behind the journals that inspired the film; he uses knowledge to share the stories of exploited and murdered communities, but does so from the perspectives of these communities. Guerra told the initially suspicious elders that his intention was simply to learn and share what he found out. “To them, that is completely valid because they believe in storytelling for these reasons”.

I will re-watch Embrace of the Serpent, I will refine my judgements, I will read more, and hopefully write more on this film. For now, I would like to thank Ciro Guerra for reminding me why I love cinema and why in my own small way I am privileged to be in a position to learn and share knowledge of Latin American film.

Sources

Guillén, Michael (2016) , ‘Embrace of the Serpent: An interview with Ciro Guerra’, Cineaste, Vol. XLI, No. 2. http://www.cineaste.com/spring2016/embrace-of-the-serpent-ciro-guerra/

Kermode, Mark (2016) ‘Embrace of the Serpent review: You will be transported’, The Guardian, June 12. https://www.theguardian.com/film/2016/jun/12/embrace-of-the-serpent-observer-review

Mathiesen, Karl (2016), Embrace of the Serpent Star: ‘My Tribe is Nearly Extinct’, The Guardian, June 8. https://www.theguardian.com/film/2016/jun/08/embrace-of-the-serpent-star-my-tribe-is-nearly-extinct

Oh my goodness! Impressive article dude! Many thanks, However I

am encountering difficulties with your RSS. I don’t know the reason why I cannot subscribe to

it. Is there anyone else having the same RSS problems?

Anybody who knows the solution will you kindly respond?

Thanx!!. Review my artifact – best cord electric lawn mowers #agreenhand