On re-editing ‘final’ versions of films: The case of NN

Today, Mediático presents an entry by Natalia Ames, a Peruvian film critic and journalist,a graduate of the MA in Film Studies, University of Sussex, and an employee of the Ministry of Culture of Peru.

On re-editing ‘final’ versions of films: The case of NN

By Natalia Ames

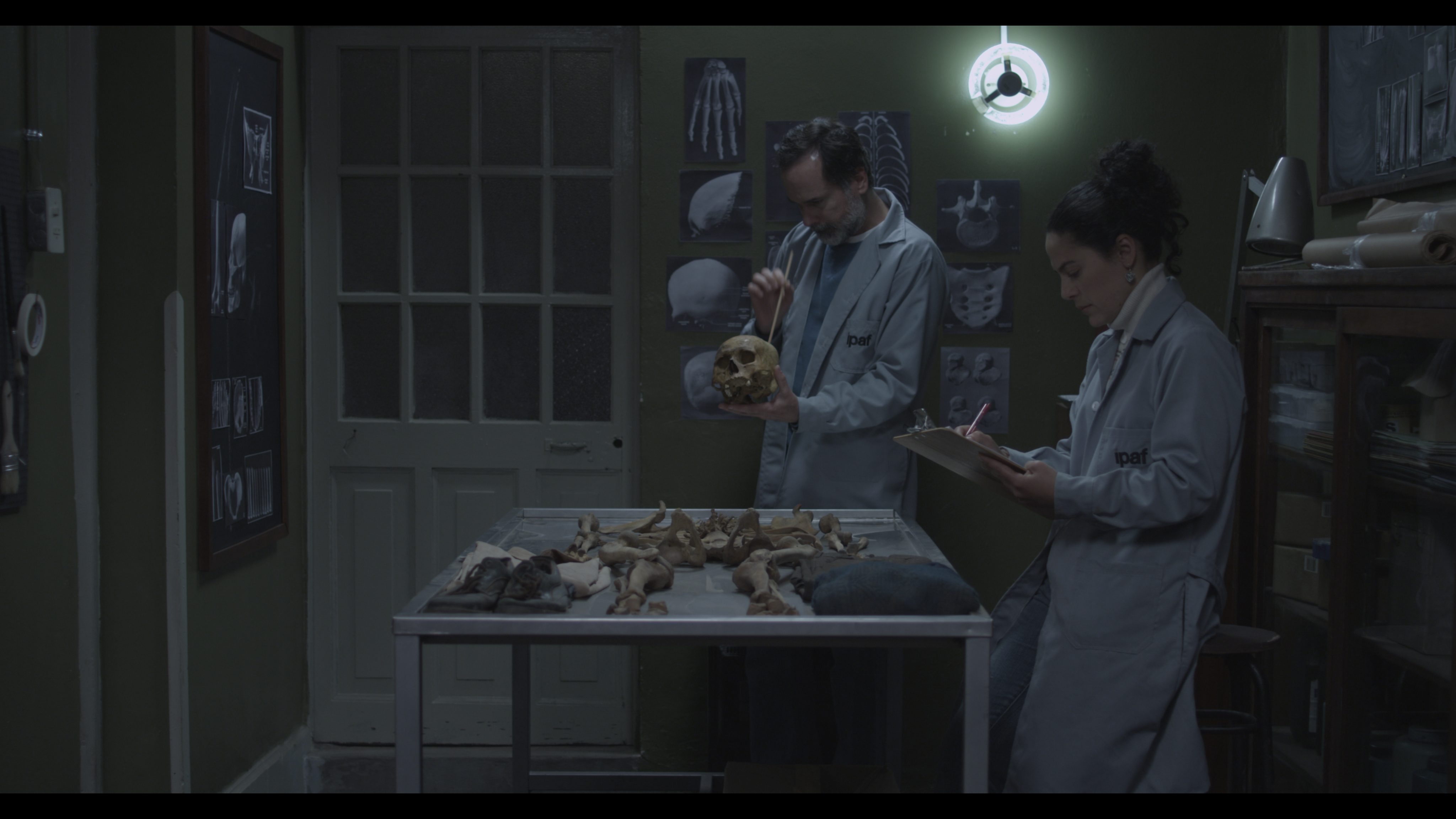

NN is the second feature film directed by Héctor Gálvez, a filmmaker who is deeply concerned with Peru’s recent history of civil violence as well as with that country’s on-going social issues which have emerged from that history. Indeed, the story behind NN (which follows the leader of a forensic team in search of the identity of an unknown body found in a mass grave) was inspired by the director’s work with human rights NGOs.

Gálvez’s directorial method, according to media interviews, is based on working with multiple versions of his films. Rewriting scripts and making various edits of his movies (both documentary and fiction ones) are integral parts of his approach to cinema; he describes himself as a non-conformist in this sense.

The re-edited version of NN, which appeared after the original version of the movie had officially premiered at international festivals, including Rome and Lima, in 2014, was heralded by Gálvez as an improvement on the previous cut. The new version, screened for the first time at the Cartagena Film Festival in 2015, received an award for Best Director. It later received a theatrical release in Peru and has since been chosen as that country’s candidate for the 2016 Oscars, a development that brought immediate media attention to the film.

In several interviews following the theatrical release, Gálvez has discussed the differences between the Rome version and the later one: he excised some footage and added five scenes, in order to make the movie less ‘dark’ in narrative terms and more ‘responsive’ to audiences. If we compare both versions, we can see that some of the scenes have been re-organised, altering the relative importance of some events and characters. Indeed, even as the main story from the initial project is still apparent, there are evident changes in the script that point to a reformulation of the leading character.

Gálvez, who hesitates when asked whether the theatrical version is the ‘final’ one (in an interview with El Comercio, he admits that for reasons of “mental health” it is necessary to bring this kind of process to an end), argues in favour of his re-editing choice on the grounds of his non-conformism and his desire to ‘lighten’ the film for audiences after seeing it on the big screen in Rome. As he declared to La República: “I believe non-conformism is part of the creative process, there is always dissatisfaction… which is the engine to keep creating”.

Yet, the case of NN raises even more complex notions about re-editing and what it implies. On the one hand, with the rise of non-linear, digital editing technologies, it is easier than ever—not only for filmmakers, but also for others—to make multiple versions of films. Indeed, a wide range of films are re-edited for multiple purposes, from (sometimes, legally tricky) fan remixes through to audiovisual essays – as forms of academic analysis or of social protest, like the Tumblr Every Single Word, in which Dylan Marron remixes Hollywood films to show the lack of representation of minority groups.

On the other hand, re-editing by the filmmakers themselves makes us wonder where to draw the line beyond which a version is the ‘final’ one. Even if the line used to be the official release (with ‘director’s cuts’ only being released later, following claims that there were strong studio pressures to release public-friendly versions), it is becoming more acceptable to re-edit a film after it has been exposed to audiences and critical opinions. Isabel Coixet, for example, re-edited her film Nadie quiere la noche after facing criticism in Berlin, taking full advantage of her right to improve her creation.

Perhaps, instead of what is a ‘final’ version of a film, we should ask when is a film finished? Are further changes allowed? And more importantly, by whom? By the filmmaker? By the audiences, whether they are from festivals or from theatres? By the institutions – for example, in the case of NN, the Peruvian state which funded and gave prizes to the non-final version of that film [1]? And lastly, could multiple versions become a way to attract more spectators to the new releases? Blurring the boundaries of what a final version of a film is might open up the possibility of further creative changes, but it also calls for a re-definition of terms as far as applications to festivals and for funding are concerned. This is certainly a debate that should take into account not only the technological factors that facilitate re-editing, but also the effect that multiple versions might have on the industry, the festival circuit, the audiences and the filmmakers’ creative process.

[1] It is worth noting that the film had received two pieces of state funding: first, as a script in 2011, for the filming process, and then as a completed movie in 2014, for its distribution and exhibition. Gálvez applied for the second amount for the Rome version, not for the one released in theatres.