Netweaving in Latin@ digital art

This week at Mediatico we present a post from new contributor Thea Pitman, Senior Lecturer in Latin American Studies at the Centre for World Cinemas and Digital Cultures (CWCDC), in the School of Languages, Cultures and Societies (LCS), University of Leeds. She works on contemporary Latin American cultural production, in particular online, and more broadly digital, works, including blogs, hypertext/media narratives, tactical media, and indigenous new media. Her current research project concerns discourses of identity in Latin American internet cultures.

Ever since I read Donna Haraway’s ‘Cyborg Manifesto’ when I first started work on Latin American online cultures, I’ve been on the look out for examples of ‘netweaving’. In particular, having also read Chela Sandoval’s (gentle) critique of Haraway’s manifesto [1.Sandoval, Chela. 1999. ‘New Sciences: Cyborg Feminism and the Methodology of the Oppressed’, in Cybersexualities: A Reader on Feminist Theory, Cyborgs and Cyberspace, ed. Jenny Wolmark (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press), pp. 247-63. [First published 1995.] which takes her to task for piggy-backing off Chicana/Third World feminism, and for littering it with references to indigenous cultures without really acknowledging their potential to evidence cyborgic subjectivities in relation to new technologies, I’ve wondered about how Latin American indigenous groups relate to new technologies, particularly the internet. What might constitute a sense of ‘digital indigeneity’? What might be the poetics of such a concept? In short, would they put indigeneity back into Haraway’s ‘Cyborg Manifesto’ and reclaim ‘netweaving’ as their radical approach to contemporary digital, networked envirmonments?

What I’ve found is that Latin American indigenous groups generally don’t and the reasons why are the subject of my current research. But what I found by the by when I went looking for evidence of Latin(o) American indigeneity and weaving online, and in digital cultural production more broadly conceived, is nonetheless very interesting work and deserves attention in and of itself. A number of digital/multimedia artists of Latin American origin, but all now resident in the United States, have been motivated to start to excavate a sense of what it means to be from their home country at some point during their time in the US. Part and parcel of this exploration of ethnic origin is the desire to explore traditional, specifically indigenous, cultural practices such as weaving and to filter this through their individual artistic sensibilities as well as the opportunities opened up by new technologies. It is this drawing on indigenous textiles for inspiration in order to produce works of digital/multi-media art that I identify as corresponding to a poetics of ‘netweaving’.

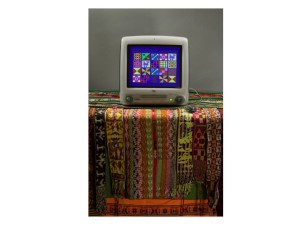

My first example of this trend is the work of Bolivian-American artist Lucia Grossberger Morales. Resident in the USA since early childhood, Grossberger Morales professes to have always been interested in textiles, but allergies sent her in the direction of digital and multimedia installation art. She sold her house to buy her first Apple Mac in 1979 and was a real pioneer in the early days of digital software design, submitting a couple of digital art programmes to Apple for commercialisation. In her work Grossberger Morales seeks ways to express herself both as a female artist and as a member of an ethnic minority in the USA, often drawing on indigenous textiles as a way of trying to adduce a (perhaps strategically essentialised) sense of authentic Bolivian cultural heritage for herself and balancing that with her contemporary US identity, cast as firmly aligned with new technology. Despite the dangers of essentialism and appropriation in this equation, the works that Grossberger Morales produces stem from substantial fieldwork and archival research into indigenous weaving techniques and meanings, and the installations themselves – original digital textiles displayed on computer screens set up as the centre pieces of ‘home altars’ draped with traditional textiles themselves, or projected onto the walls and ceiling of the exhibition space – are visually striking and conceptually engaging. Her Pallai: Digitally Weaving Cultures installation, first exhibited in San Bernadino in 2004, and Lightbox Mágico (Cochabamba, 2009) are good examples of her work in this respect.

Moving on from Grossberger Morales’s multimedia works, Guillermo Bert, an artist of Chilean origin now resident in Los Angeles, approaches the topic of netweaving in a particularly innovative transmedial manner. His Encoded Textiles: A Blank(et) Canvas for the Native Peoples of the Americas (Pasadena Museum of Art, 2012) stems from original interviews with members of Mapuche communities in Southern Chile regarding their beliefs and cultural practices. Bert transformed very brief extracts of those interviews into Aztec code – a form of ‘bar code’ that works with a square grid like QR-code but has only one set of concentric squares in the centre of the grid – which he then asked weavers from those same Mapuche communities, such as Anita Paillamil, to recreate as part of a traditional textile design. The idea is that a QR-code scanner on a mobile phone should be able to scan the resultant textile and get back to the original fragment of information about Mapuche lifeways. The textile below for example, entitled ‘Ancestral Spirit’, decodes to read ‘Tenemos las mismas necesidades del árbol, no podemos vivir sin tierra’. When exhibited the textiles are also accompanied by short video documentaries regarding the story behind each textile. The transmedial approach in Bert’s work – the move from traditional, offline craftwork to digital ‘design’ and then back into a transformed piece of craftwork – is particularly valuable for its ability to not simply draw inspiration from indigenous art but to integrate indigenous participants in the design, execution and exhibition of the works.

The last artist whose work I’d like to present here is Monika Bravo. Born and bred in Colombia and now resident in New York, Bravo is a very talented artist across a whole range of media. However, rather than select a multimedia or transmedial approach as per Grossberger Morales and Bert, in her work that deals with weaving – URUMU [WEAVING_TIME] (2013) –, Bravo opts for a large scale video projection that covers three walls of the room in which it is displayed and completely envelops the viewer in a fully digitally mediated experience. (For a short video that gives a sense of the way at least part of the projection works click here.) The projection offers the viewer an experience of a dynamic, digital weaving process taking place all around them, in combination with images of the Colombian landscape that fade in and out of the woven texture of the video.

Bravo conceives of the piece as having potentially different meanings for different audiences. For a non-Colombian audience, the piece may well come across as signifying generic Latin American-ness in conjunction with indigeneity. (As for Grossberger Morales, the two are easily harnessed together, particularly as these artists play with the stereotypical conceptions that outsiders have of the region.) For a Colombian audience however, Bravo knows the weaving motifs, even in a different palette of colours, will evoke the ‘mochilas arhuacas’ that are now found throughout the country and sold as tourist souvenirs – they have become something of a symbol of Colombian-ness per se in recent years. But finally, Bravo is clear that for the Arhuaco (or Ika) people of the Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta, the weaving motifs each have quite particular meanings and it is these meanings that she is working with, as alluded to by the title of the piece (Urumu means snail, and by extension spiral of life, the universe in Arhuaco cosmology). This artistic project is based on regular fieldwork trips to the indigenous communities concerned spanning a period of several years and evidences a subtle and respectful approach to its indigenous sources of inspiration. It is also a highly original artwork that responds directly to the artist’s desire to express her own ‘emotional geography’ in her work.

Overall, the ‘netweaving’ projects of Grossberger Morales, Bert and Bravo manage to avoid the pitfalls of indigenism, though clearly there are always issues that arise in this respect in any work made by non-indigenous cultural producers ‘exploiting’ indigenous cultural materials or knowledge. These artists demonstrate a conscious desire to avoid indigenist perspectives through extensive research into indigenous cultures and weaving techniques and/or through the involvement of indigenous communities in the creation of the works themselves. Furthermore, their ability to produce engaging and highly original works of art that balance the tactile qualities of textiles with the ‘ungraspable’ nature of digital art in a particularly satisfying way tends to achieve all around acceptance, both by indigenous communities and the international art world.

Email: t.pitman@leeds.ac.uk

Twitter : @TheaPiman

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/dlacnet

[…] Thea’s post on the poetics of ‘netweaving’ in digital art projects by Latina/o artists Lucia Grossberger Morales, Guillermo Bert and Monika Bravo has just been published in Mediático, an online media and film studies blog focusing on Latin American, Latina/o and Iberian media cultures. To read the full blog post click here. […]