Letter from San Antonio de los Baños (EICTV)

This week Mediático presents excerpts from the diary of José Arroyo, Principal Teaching Fellow in Film Studies at the University of Warwick, recently returned from lecturing on ‘The Cinema of Ernst Lubitsch’ and on ‘The Musical’ from March 14th-31st at the Escuela Internacional de Cine y Televisión (EICTV) [1.EICTV (Escuela Internacional de Cine y Televisión) in San Antonio de los Baños, Cuba, was recently voted in the top five film-making schools to watch by The Hollywood Reporter. The school was founded in 1986 by Nobel Laureate Gabriel García Márquez, Argentine poet Fernando Birri and the Cuban producer Julio García Espinosa with the support of then-President Fidel Castro in order to provide as close to an ideal context for students from the ‘Three Worlds’ of Africa, Asia and Latin America to study filmmaking. The three founders dreamed up an ingenious system of workshop-based teaching where directors, sound men, cinematographers, critics, academics and just about anyone involved with any aspect of film culture arrive for a two week period, teach what they know, and then the same mini-bus that returns them to the airport brings in a new set of skilled people willing to share their knowledge. It’s a very effective system and one available now to students from ‘Todos los mundos’/ All the worlds.’] in San Antonio de los Baños, Cuba. This was his fifth visit to the school. He has been a columnist on gay culture for Angles in Vancouver, currently writes ‘The Wide Lens’ column for The Conversation and has contributed film criticism to a range of media outlets including Sight and Sound magazine, Attitude, Jump Cut, Cine Action, Front Row on Radio 4, The Cinema Show/ The DVD Collection for BBC TV and many others. José has taught Film Studies at a variety of institutions, including Concordia University in Montreal, Ramon Llull University in Barcelona. He currently blogs on film at notesonfilm1.com.

Cuban Diary – Day 1

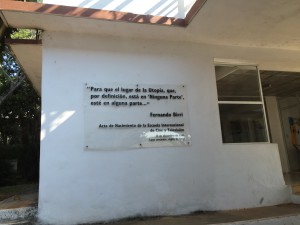

‘So that utopia as a place, which by definition is nowhere, may be somewhere’, Fernando Birri.

Arrived in Cuba yesterday, on time for a change, and extremely efficiently due to their new and revamped VIP Service. The whole process between arriving and being met by a driver once through customs took less than an hour. One had time for a glass of ice-cold water while someone else took care of everything else, including getting your luggage. It’s a life one could easily get used to.

It had rained the day before I arrived and its imprint remained in the form of a light mist that enveloped one and smelt clean, damp, earthy. Above, was a sky one only sees in Cuba, clouds, palms covered in fog, and a light — a mixture of orange and pink — that cast a romantic glow over the landscape and thus into one’s life.

We passed various villages on the way to EICTV, crashing through puddles of water that hadn’t yet drained, fearful of running over pedestrians and perhaps killing cyclists whose bikes had no reflectors whatsoever. It’s quite an image, couples particularly lovely, the ladies side-saddling on the cross-bar and leaning their heads back onto their man’s shoulder. But I noted that even trucks had no lights. Maybe they’d broken. Maybe the driver couldn’t afford new ones. No excuse not to drive. One’s livelihood might depend on it.

As we drive into the film school, and to the frustration of the driver, we get stopped by the police. The driver’s asked to get out and show his papers and he does so very politely. ‘Hello Brother’, ‘Were you wearing a seatbelt?’, ‘Of course’, ‘I don’t see your passenger wearing one’. But as I lean to say hello, the belt hits the light and it becomes clear I am wearing one. After the boot’s been searched and we’re waived through, the driver starts:

‘Anything to make your life difficult. The other day I was taking my girlfriend out for a drive. My girlfriend mind you, not my wife, and we get stopped. I’ve been driving this car and passing through here three times a day for forever. They all know me. But I get stopped and asked for papers whenever the mood hits them. Well I gave him my papers but, wouldn’t you know it, my girlfriend didn’t have hers. ‘What’s she doing without her papers?’ ‘She forgot them, we didn’t really plan to go out.’ ‘Where are you going?’ ‘For an outing.’ ‘Why don’t you just go out in your own village?’ ‘Officer, how can you expect to take my girlfriend about town with my wife and children there?’

‘Can you imagine, the bastard? And what’s worse, he’s married to a girl from my village. They made me drive back into town and get my girlfriend’s papers to prove she wasn’t a jinetera (a term that describes a mix of services from guided tours to prostitution but with strong connotations of sex for sale). And then, to top it all off, they ask me how can I afford to drive such an expensive car. It’s the school’s car not mine. But I told him that so long as it wasn’t stolen and I had a right to drive it, it wasn’t any of his business. My whole life I’ve known that bastard!

Sunrise over EICTV

Day 2

I love the EICTV. I also know Cuba is hard up, thus so is the school, and I generally take everything I’ll need with me, not only computers, films, hard drives but also adaptors, plugs, cables. I’d even brought my own coffee machine and coffee. I know, it seems ridiculous to bring coffee to Cuba but there was a time when I simply couldn’t find any in the school or the surrounding. It took a long time to not find. I could only get to Havana on the weekends and I thought it best to come prepared.

And I thought I was. But once I settled into the flat the school provided, I go make myself a coffee and find there’s nothing with which to light the gas. I called the superintendent and she said that she could give me a light but that I’d have to bring it back as she couldn’t spare the lighter. The same was true of the nice man who runs the school’s coffee shop. It seemed there was not a lighter to be spared in the whole of the school, and the shop that sells them wouldn’t be opening until Monday. Oi! I take one last look through everything I brought and find an old lighter in my toilet kit. Hoorah! I go light the brand new stove — recently installed — to start the espresso and now the gas doesn’t work. Grrrrrr! If it’s not one thing, it’s another; and saintly patience is sometimes required to get even the simplest tasks done. Everybody’s nice; everybody’s helpful and kind. Everything will eventually work. But not now and we don’t know when.

Walking through Havana, I head towards the Café Balear, there’s a queue and I can’t get in, but through the grilled gate, I see middle-aged couples dancing and hear Ruben Bladés sing ‘mi hijo, mi niño, nuestro niño’. For some reason to hear Bladés sing in Havana makes me ridiculously happy. I wish he’d know about the joy and dancing he’s sparked on the Avenida de los Presidentes.

In the Café Literario ‘G’

One of those moments only transnational emigrés are familiar with when something, a phrase, a few chords from a song, some meaningful madeleine from the old country overwhelms you simultaneously with the emotion evoked by its association with the past and the deep loneliness of knowing there’s no one in your current life with who you can share the meaning of it. This is sparked by someone familiar but who’s name I can’t quite remember singing ‘porque en las cosas del amor soy un idiota, he conocido mil derrotas’….

***

Almost everyone knows Jennifer Lopez is a star; and anyone who knows anything about Jennifer Lopez knows she was once married to Marc Anthony; but in the Spanish- speaking world everyone also knows that Marc Anthony is at least as big a star; and anyone who knows anything knows Marc Anthony is an artist, one of the all-time greats. For some reason Marc Anthony will turn out to be the singer who I most often hear on the radio, portable phones played loudly, or music coming out of cars and homes during my stay in Cuba. That and a mix of Cuban hip hop rappers singing reggaeton.

Bar in O-Reilly

A new bar’s opened up, a gin palace that offers trendy tapas and spectacular cocktails. I wonder why it feels so sophisticated and modern and I realise it’s just the finish of the place. Everything’s straight, everything fits, and everything’s clean to the point of sparkle: Unusual in Havana. But perhaps more unusual is to spend a worker’s monthly wage on a couple of hours’ worth of cocktails and tapas however gorgeous and inventively named (I had a Margaret Thatcher, a Daiquiri, a Cacharán and a mojito before swaying out).

A Strawberry Daiquiri, now available in Old Havana, on O’Reilly

Monday Week 1

I’ve been discussing the series of lectures on Lubitsch I’m planning with Jorge Iglesias, wise and considerate head of humanities for the school, and been politely warned not to start with Lady Windermere’s Fan. Attendance is voluntary in these open lectures and one doesn’t want to alienate students with what are seen as three strikes against the choice: a) film is silent and in black and white b) the only copy available is one with English sub-titles, and though there are not many in the film, it might put off the Spanish-speaking audience, of whom many might be able to get by in spoken English but might have greater difficulty reading it and c) my own Spanish. I left Spain when I was seven and since then I only speak Spanish with my parents, and then not too often, so my vocabulary is restricted to home matters such as ‘how’s Aunt Mary?’ or ‘please pass the salt’.

Marco [Olmos] comes to see me to thank me for the classes last year as does Miguel Angel Moulet, who took my class a long time ago and is now teaching here. It’s what a teacher lives for, to know they made a difference, opened some doors, introduced some ways of thinking. It makes my day. Marco also brings me a copy of the short film he worked on with Héctor Silva Núñez, Anfibio (Amphibian), now accepted at Cannes, and he hopes he can raise the funds to go there. He’s already lived in Liverpool for five months he tells me, found the city exciting but the weather hard.

Students are adoring Lubitsch. How could they not one might ask? Yet, these things are never a given, one is always surprised by what they take to, what they resist, what they need a little nudge or a different perspective with in order to change their appreciation. Here for example, the clear favourite is Lady Widemere’s Fan. Students loved the elegance, the simplicity, the geometry, the melodrama. In England, my students found it dull. It was silent and black and white and perhaps I spent too much time trying to convey to them theories of aesthetics and not enough pointing out why this is such a great work of art.

Meet up with an old friend. We talk about the changes happening in Cuba at the moment; the private businesses cropping up and the incredible imagination and initiative that they demonstrate; like the gin palace I went to on Saturday; a gin palace in a country where there is no gin; people walked in off the street every so often selling a bottle; every daiquiri or ‘Margaret Thatcher’ mixed was accompanied by a deal from one merchant or another walking in from the street – frozen strawberries, French pastry, liqueurs; all the while the barman mixed you the drink, shared his bonhomie with you, produced something of stunning beauty, whispered in someone’s ear, made a deal, bought something and took the very considerable amount of money you were happy to pay for such a great ambience and such delicious fare.

‘The Package’: How do Cubans seem so ‘au courant’ so well informed and so up to date on all the latest technologies when there’s only official channels on television and there’s very little internet access (and none for the majority of the population)? Well, it’s because of ‘The Package’; every week up to three tetrabites of information – films, TV series, software – illegally enters the country and people can for a modest sums buy parts of it on the black market – thus Game of Thrones and all the latest series from the US and all over the Spanish-speaking world can seen in Cuba only days after they’ve been broadcast at home. Supposedly, at the last Havana film festival, a Spanish comedian whose name I didn’t quite catch was greeted with wild applause at the screening of his film, the whole hall packed with his admirers cheering him on. None of his work had officially been exhibited in Cuba until then but his TV work in particular had incurred an enthusiastic fandom courtesy of ‘The Package’.

Heaven Can Wait (1943) was our last film in my series of talks on Lubitsch. Still had a vey big turnout though the film was long, ended at around midnight and the discussion afterwards was tired. However, as soon as everyone hit the bar, had a drink and relaxed the talk continued. All everyone needs to do to become a convert is to see the films. They saw, and they wanted to see more and it was rather thrilling to talk to all of them. The faults one saw – Don Ameche’s relative lack of charisma, the hideous make-up on Gene Tierney, the garishness of the colour – were not evident to them. And they particularly adored the skit with Eugene Palette and Marjorie Main back in Mabel’s Manse in Kansas, spatting over the funnies. And indeed it is a comic masterpiece.

Had a long chat with a Spaniard from Segovia who knew the village where I am from El Barraco. That’s the kind of place EICTV is; one meets people from all over the world, some who even know one’s home village, and all passionate about cinema.

Had a day in Havana yesterday. We got driven there and had a long chat with the driver who is called El Grande because he is very big and was the number two weightlifter in Cuba in his day. He’s so in love with his wife it makes me sigh. He brings her breakfast every day before she gets up; she’s a wonderful cook and he describes all the various dishes she makes with mouth-watering relish; then I realise the reason he’s doing so is because, as he tells me, he might be developing gout and the doctor has forbade him red meat, fat, alcohol and salt. ‘Red meat’, he says ‘imagine! As if anyone on my salary could eat red meat. Where do they get these notions?’ Anyway, he’s been lucky with his wife, they’re still in love, they still dance on Saturdays and she loves him so much that she’s got an eagle eye on him and makes sure he doesn’t eat any of the mouth-watering dishes she cooks for the family but sticks to the boiled rice she’s prepared especially for him. ‘What a woman! I’ve been lucky. She looks after me.’ They’re worried about their only son. He was a registered physiotherapist but with all his education his salary was about 500 pesos, 150 more than his father but even so, a pair of shoes is 20-25 CUC’s, a shirt 30, i.e. at an exchange rate of 1CUC for 25 pesos, one such item of clothing eats up your whole month’s wages. Who could live on that? He gave up his career and is now managing to make a living as a builder.

The fabulous forties interior of the Teatro Meller

I must have been a in a bad mood, probably made worse by being ill. On the way back to San Antonio, at around 11 pm, windows were open, and I must have caught a chill. The police stopped the bus, two young boys, dressed to the nines, obviously gay, the cops put the kids on the bus; one sat next to me and asked where is the bus going? It amazes me that they took it so naturally, in the middle of the road, in the middle of nowhere, not knowing where they were going, and obviously at ease, having a good time and expecting to have some fun. The lady in front of us very kindly informed them when it was time to get off as otherwise they’d have ended up at the school without hope of further transport elsewhere. I mention this to a friend later and he tells me, ‘you might not know were they were going but they most certainly did and clearly expecting a good time at the end of the trip.’

I woke up with a terrible cold, sneezy, nose running, completely debilitating cold. It got worse as the day progressed so I went to the doctor.

‘Drink plenty of water, gargle with salt, take this medicine. ‘

‘How does one get it? ‘

‘In San Antonio.’

‘Well, how does one get to San Antonio?’

‘One gets on a bus that might leave at…..’

Since I barely had the energy to stand up much less get to another town where there’s barely any transport and where I don’t know where anything is…I tried to arrange for someone to buy the medicine for me. Come back at two, he said. I return at two and the person I’m supposed to meet is not there. I wait. I get annoyed. I don’t know how I’m going to be able to talk that evening when I can’t control all the bodily fluids that are oozing from me. A kindly Swiss lady offers me some cold medicine she’s brought with her; I’m able to introduce the musical genre and my choice of film – Swing Time (George Stevens, 1936) — and that goes very well but can’t manage to sit through to the discussion after (it’s a 3 ½ hour process altogether). I hear later that it went well, nobody walked out but students weren’t that keen on the film. I feel sure I could have made them keen and am angry I couldn’t get the medicine I needed to talk. But then I see I’m being unreasonable…it’s Cuba; it might not be available anywhere except Havana. It’s a day later now and I still don’t have it though I’m feeling much better.

Meagre turnout for Meet Me In St. Louis (Vincente Minnelli 1944). Too bad. I would say they only turn out to that which they’re familiar with but the film wasn’t advertised so maybe it was just me. I overdid the clips at the beginning, did a full hour presentation before the screening, which when you start at 9 pm is making quite a few demands of them. There were only six diehards left for the Q and A after the film. I expect fewer people today.

My hands are covered in little red dots from the humidity. There are also big red welts next to anything that’s put pressure on my skin: belts, bag handles, even shoe laces. Plus my body is covered in mound with a piece of flesh missing, the piece the mosquito or fly or whatever has taken a big bite off. My juicy lardy sweet self is obviously proving a feast for Cuban insects.

Very interesting talk with a former student about musicals in Cuba; he worked on the latest Irremediablamente Juntos (Jorge Luis Sánchez, 2012), a hugely expensive disaster he tells me. It cost, 3 million CUCS, a fortune in a place where 336 pesos nacionales, under 15 CUCS, is an average monthly wage. He said the director went crazy with the camera, didn’t quite know what he wanted, so it was all dollies and cranes and wild movements all over the place that didn’t make sense. He was very informative also on why musicals are inherently more expensive, costumes, music and dancers aside (and that’s a big aside), they often require multiple cameras and more post-production. I’m always surprised that a culture with such a prodigious musical legacy has produced so few musicals. However, documentaries on musicians and music are luckily plentiful. I’m also told about Havana Blues (Benito Zambrano 2005), which was a big success several years ago. I think I’ve seen it but seem to remember it as a Spanish film about Cubans in Madrid. Now not sure. [Editor’s note: José’s memory is correct – here is the entire film on Vimeo] Need to see both of those before I leave.

Good turnout again yesterday. Students are in the middle of their final thesis work and under a lot of pressure; so they’re congratulating me on my big turnout of about thirty people on a Wednesday at 9pm. I was very happy with it and we had a very good discussion after Singing in the Rain (Stanley Donen, 1951) on how, great as it is, there are things not quite up to the heights of the very greatest. Isn’t Kelly just a teensy weensy bit hammy; aren’t the songs a bit derivative and unexceptional?; should the theft of Cole Porter’s ‘Be A Clown’ for ‘Make ‘Em Laugh’ be forgiven?; isn’t Debbie Reynolds a bit too bland to be the new ‘most brilliant star in the fih-mah-mehnt’? isn’t it a problem that the only bits one remembers of that endless Broadway Ballet aside from its ending are the few minutes Cyd Charisse is in it?

Bigger turnout for Funny Face (Stanely Donen 1957) yesterday; I think I’m finally turning them all into enthusiasts; they’re loving the films and being able to talk about them afterwards; and they’re telling their friends so numbers are on the upswing, always pleasing. I’ve turned all of them into Fred Astaire worshippers (not hard); and I think the women in the audience yesterday felt particularly addressed: Audrey of course, and Paris, and the fashion show. It’s a pretty gorgeous film to look at, though a Brazilian student, Denise I think, rightly pointed out that it’s attack on intellectualism is troubling and needs not go hand in hand with its love for and defence of the superficial. Students adored the use of colour, the technicolour range of offices at the magazine, then the use of pink in the ‘Think Pink’ number, then the browns in the bookstore lightened by that hat with the lime, yellow and orange trimming that is as seductive to Audrey as another hat was once to Ninotchka. Being film students, they loved the inventive use of various elements of film form, the scene in the developing room where Astaire prints out a new image of Hepburn, the face of ‘Glamour’ woman or whatever the magazine is called, and particularly the red light over-hanging the darkroom but the whole process itself, the printing into black and then the adding of various chromatic ranges, and the fashion show accompanied by a story and captured as a still where the film gets arrested and Audrey looks beautiful and iconic, the person rendered into image, flesh into a structure of printed shadows and lines. The screening broke down five minutes before it was due to end, just at that moment when Hepburn is about to whack Professor Flosse over the head with an expensive statue. This being Cuba, we didn’t know why. The print seemed fine, the wires were connected, the player seemed alright. It took us about 15 minutes to test everything; then when we finally did, I simply re-started the computer from scratch, started the film where we left off, which seemed to do the trick, and we finished the screening being none the wiser about why the sound had gone off before.

Had a drink with Héctor after the screening. We talked about his films and his plans. He’d been a social worker in that coastal town off Maracaibo in Venezuela and based his film Anfibio on a kid he’d known, worked with and corresponded with long after he’d quit that job. But when it came time to act in it, he backed out. Hector’s lived in Bournemouth, with a family he describes as like the Simpsons. They put him in a loft so they’d have the least possible to do with him he says and all they did was come home from work, put something on a plate for dinner, and glue themselves to the TV.

My course on the musicals ends on a high. Good turnout. Show Les parapluies de Cherbourg (Jacques Demy, 1964), which everyone loves and there’s a very stimulating discussion about the complexity and contradictions of the ending. ‘That’s what real love is’ says a member of staff about the hero marrying his aunt’s carer. ‘Well I’m 26 years old’ says a student and I wanted it to be like they felt at the beginning – the intensity and the longing; the joy and despair – and not where they end up at the end which feels like settling for the best of limited options, a compromise’. I think the film indicates that too. His not wanting to meet his daughter who bears another man’s name; his telling her it’s time to leave. He has feelings for her and one feels that if she’s there a moment longer, he’ll break down. But then she leaves, his wife and his child arrive and he starts playing and you get the sense that he’s happy; yet the camera pulls back and you see the white petrol station, an isolation and a bleakness, both pretty and thus bearable but also rather empty. They’ve found a life that will shelter them from the worst of life’s circumstances but it’s an umbrella that can’t be shut down and put away to let the sunshine in once the rain’s gone.

There’s a joyous celebration after the last screening where lots of mojitos are drunk. I’m joined by Emiliano, a documentary filmmaker from Uruguay, Eduardo, an Art Director from Mexico, Reynal, a Cuban production manager and many others. Emiliano and I know people in common: Sergio Miranda, the first gay person to get married in Uruguay and head of one of the biggest marketing companies in the country; and Sergio De Leon, a 1st a.d., both of whom I ‘ve met here through the school. We watch the kids dance and I tell him that one of my great joys in Cuba is to see just that how beautifully people move. He tells me there’s something about being near the equator where the further up you go, the worse people dance but it’s also true the further south you go ‘You see that big group on the left?’ he asks me. I look at a group of young people with some very short women who are making moves the professional dancers on Strictly Come Dancing would envy: ‘they just arrived last night from Puerto Rico for a workshop. But you’d never know it. On the dance floor, they own the place.’

I haven’t given up on my project of doing a video essay. So I’ve managed to get a copy of Premiere editing suite. A lovely man, Mateo I think, Italian, the one who always commented whenever he found a crude edit or jump cut in a musical number, installed it for me; and then I got a lesson from a lovely young girl who’s attended almost everything I’ve taught. I must find out her name. I didn’t get very far. I am feeling old. These young people, their fingers race over my Mac and make it do things I didn’t even know it could do. And it’s hard to keep track of the myriad commands. However, I was able to make a simple clip from an avi (which I remember how to do) and even put a title on it (which I don’t). My brain really couldn’t process more. There is no instruction booklet. I’m hoping to get one when I get home and make that my summer project.

Returned to Havana yesterday Sunday mainly to go to the theatre; there’s a production of Decameron I wanted to see. The coach left from the school at noon so I could have lunch here before leaving, get there in time to do some light shopping, have a mojito or three, and go to the theatre. The first part worked out but I could not get tickets to the play. They go on sale an hour before curtain’s up and even though I got there with half an hour to spare they were already sold out. I went instead to the Mella Theatre, where they had a comedy show. The theatre is a gorgeous Art Deco dream of a theatre but the comedy was second rate. There was two skits by three comedians, one in blackface, which really didn’t go down too well; then a man in drag who was quite funny though the humour was rather low and somewhat racist (mainly how to get Russian, Italian, Roumanian and French names to sound like downright dirty phrases in Spanish but with the appropriate foreign accent). And like the Woody Allen joke [in Annie Hall] about the women who complained about both the quality of the food and the meagreness of the portions, it was too short; so rather than having an hour or two to kill, I had four; and then the whole thing became a strain. Arguments about a ridiculous service charge (it’s a trap, they show you the menu, the prices look expensive but not completely over the top, and when the bill comes it bears no resemblance to the menu and you realise a service charge has been added. What makes it seem even more of a con is that not all establishments add a service charge). Then an argument with one of those mini-cycle drivers who wanted to charge me half the average monthly wage in Havana to travel 2km; and then you think why argue; either accept it or not; most of the time it’s not even the money (though that cab drive would have been expensive even in England) it’s the feeling of being ripped off; and if one is going to be sensitive about those things, one can’t really have a good time in Havana; and sadly I am sensitive to that; I don’t pay too much attention to it but when it becomes obvious and people blatantly try to con you with such extraordinary cheek, it makes my blood boil and spoils every pleasure.

Coming down the grand marble staircase from the Guayaba restaurant.

Went to eat at ‘Guayaba’, the place where Strawberries and Chocolate was filmed. Dotted with photographs of Queen Sofia and Beyonce and Javier Bardem and all the other stars who have eaten there. It’s like eating in the ruins of a palace, all marble, and shining but with whole sections of it having crumbled away. The structure of the remains of the architecture however still evokes a certain grandeur; and one feels taller and seems imbued with better posture just by being there. The food, however, whilst extremely good by Cuban standards, left a lot to be desired by the international standard invoked by the prices it was charging. An attempt to do elegant minimalism, which requires concentrated fresh flavours, would be possible in Cuba but not when you’re serving lechón or tarte tatin. Anyway, my guests were thrilled, which was the important thing. I spent 150 CUCs on a meal for three, about a hundred pounds, more than five months’ wages for a worker in Cuba. I was delighted to be able to do it. But something to think about.

Met a friend of friends, a writer, walking down Old Havana, very dapper and well turned out, with an elegant cane but with the bushiest nose hairs I’ve ever seen, like mini-afros on each side of his nose. He was completely charming and told a funny story about going to a conference at the Writer’s Union and the American influence and everyone using words like ‘Afro-Caribbean’ and someone getting up and saying ‘Yo no soy ni Africano ni Caribeño; yo soy un negro de Matanza/ I’m neither African nor Caribbean; I’m a black man from Matanza’.

A girlfriend, now in her early sixties, tells stories of being young and swimming at the beach and how all the friends would gather at a particular beach; ‘It was like the Montmartre of Cuba’, she says, ‘all the writers and poets and painters except we didn’t have absinthe; we couldn’t even afford rum, it was just plain water. But we had Beatles records and we talked and swam and danced and had a fantastic time. Que me quiten lo bailao (they can’t take away that which you’ve already danced)’.

Met another Spanish girl, Alejandra, from Valencia. But she’s studied in Liverpool and NYU and Goldsmith’s and is intimately familiar with all the doings at the BFI. She’s here making a film on barbershops. They’re gorgeous places of course, all in a pre-revolutionary time-warp and with that wonderful Cuban make-do-and-mend attitude. She talks of one place where a young man, a teenager, had a salon in the front room whilst his mother ran a substantial kindergarten of over ten children in the back room. Her fascination is not only the physical places themselves, or even the social dimension of the barbershops but the actual haircuts. It seems that in Cuba, because clothes are so expensive and the selection is so bad and there are so few options, hair is the main vehicle for personal expression in terms of fashion. Great attention is paid and it’s an expensive process. Kids save for their haircuts. Here in provincial San Antonio, it’s ten pesos for a haircut. But in Havana it’s a whole CUC (25 pesos); the haircuts are modelled on the leading singers (the big stars here) and are named accordingly. They take a very long time, partly because Cuban hair, at least in some of its many varieties, can be hard to work with, and partly because the cuts are so intricate, and often have logos and flags shaved into the scalp, and quite bright and artificial colours added in at the end, even for men. ‘The whole colour thing is interesting and unusual here’, says Alejandra, ‘I was very firmly told that in Cuba, pink is a man’s colour’.

Go into Havana yesterday to see Decameron again. Again, I didn’t get to see it. This time the air conditioning wasn’t working and the theatre was shut until it gets fixed, which is who-knows-when. Again, I went across the street this time to the Raquel Revueltos theatre. It turned out it was Fourth-year Theatre students performing their graduation show and thought I’d give it a go. I turned out to be just about the worst thing I’ve ever seen on stage. Young kids, some still awkward in movement and shy and nervous, miming pain, and love and being raped, and being victims of crime, and cradling babies; all arranged on stage to create patterns but with faces always out front. The embarrassment was acute. The only entertaining came from a member of the audience, clearly a parent of someone on stage, who just after the speakers reminded everyone to turn off their phones and just as the music came on and the actors began their mime, got up and started a very vocal fight with a lady sitting nearby ‘I warned you those seats were reserved’. Very polite language, very agitated and loud voices, big shuffle of seats as the students struggled on with their mime. One died for all of them.

On the bus (they call it the guagua, a term I like so much I feel like saying it just for the pleasure of the sound), I start a conversation with a handsome young cinematographer. He says Mexico DF itself is safe and there’s little violence in most of the South of Mexico but then he’d never have imagined Mexico would become what it now is, which is a failed state, with the government waging a war on organised crime which it’s losing. The collateral damage is the citizenry. They’re driven out of their homes and businesses as the narcos and big business use drugs as just one more form of commodity exchange, another form of hard currency with which to do business so they can frack up all of the country’s resources and take them elsewhere. In the meantime, bodies keep cropping up. He tells of filming in Ciudad Juarez on a documentary about the discovery of young women’s bodies, which kept appearing periodically and systematically, as signs of warning to a rival gang. The production received death threats but hired local security to protect them and there was no incident during the shoot. We also talk of the recent killings of those students who seemed to simply have disappeared, 46 of them I think, and whose bodies are now appearing sometimes with half of their faces missing, the skin ripped off, some with slits on the side of their stomach as if they were a badly made purse: all warnings about something to someone. Yet they were once people with lives and hopes; one could say they were unlucky and got caught in the crossfire, but it seems the whole country is a context for crossfire now — A failed state. It’s so sad and bewildering and horrifying that his country has come to this; he never would have imagined it as a young man he tells me. Then he begins to talk about a director he’s worked with who was [Alfonso] Cuarón’s mentor. One of his films is about to receive a Criterion release and we talk about how this is the current form of consacration, like the Cinématèque Française doing a retrospective of a director’s work in the 50s and 60s.

In the evening I meet with a former student, a Peruvian screenwriter, already the winner of two international prizes, including one at Cannes, and his wife, a Cuban actress. At the table are also two other girls visiting from Lima, a cousin of Miguel Angel’s wife, an Habanero who’ve been drinking all day and give advice on how to combat hangovers – a local anti-depressant and an aspirin with plenty of water seems to be the magic cure and guaranteed to keep you drinking all day. His wife confirms the efficacy of the cure, though with a rather sad expression. Also present is Abel, once an executive at a major Spanish football club and now doing a workshop on screenwriting. What I get from the evening is that the average wage in Cuba is about 15 US dollars a month whilst it is about 300 in Lima. The girls from Lima are loving the climate, the ambiance, the architecture of the city and the prices. They find everything cheap. The restaurant is a popular place; there are queues. Local people. It’s right by the hotel Havana Libre but on a side street at the back. Very good food – Abel orders lamb and gets a whole front leg — and very cheap, though obviously out of reach for the general population; yet clearly not all; we’re the only tourists here, though half the table is local, and the others tourists from richer but still poor countries. It’s only Abel and I who come from first world economies for whom these prices would be really cheap. Yet as we head back to the school, the locals are off dancing to a new dance place called La Fabrica, a disco in a derelict factory, which on weekends fills its capacity of 4,000 people, and where CUCS are the only currency accepted. Someone is raking it in and, when change happens in Cuba, which everyone expects will be soon, these are the locals who will be in the best position to gobble up much of the local economy; as to the rest….The preconditions for massive inequality are already in place.

A homemade feast

Have a lovely dinner with friends at their home. They’ve gone all out. Within the limited means available they’ve created a feast. I’m very touched by all the trouble they’ve taken, there’s a beautiful table arrangement, carefully selected from the flowers that grow wild in the aerea, we mix Daiquiris and mojitos, there’s a spread of steamed vegetables which are a delight to the eye, salad, even steamed chicken. The highlight is local fruit, the meat and vegetable courses are interspersed with a compote of guanabana and chirimolla, absolutely gorgeous, but the highlight was baked mamey, which tasted like the most delicious crème carmele one’s ever tasted, but with a greater complexity and depth of flavour. Truly sublime.

I love EICTV and am always inspired by the dedication of students and staff. They seem to live and breathe cinema; I also love the workshop system of teaching there, where experts in all areas of filmmaking come in from all over the world to teach students what they know; then, as they leave, another set of tutors arrives. There’s practically nothing else to do there except attend lectures, screenings or talks; exercise; or have conversations about cinema so I always learn a lot whilst I’m there and have never ceased to consider their invitation to return an honour. It seems to embody Fernando Birri’s ideal of creating a utopia of the real in the here and now; at least when it comes to Latin American filmmaking and cinematic culture more broadly. It’s an extraordinary place and I hope it survives the changes everyone is awaiting to happen imminently in Cuba.

José Arroyo

[…] Delighted that Mediatico has published excerpts from a diary I kept whilst teaching in Cuba. It can be accessed here: https://reframe.sussex.ac.uk/mediatico/2015/04/20/letter-from-san-antonio-de-los-banos-eictv/ […]

[…] LETTER FROM SAN ANTONIO DE LOS BAÑOS (EICTV) […]