Watching John Greyson

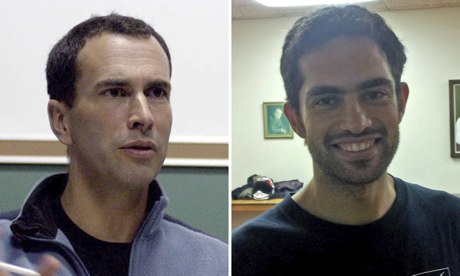

At GQC, we’ve been following closely the incarceration of Canadian filmmaker John Greyson, along with emergency doctor Tarek Loubani, who were held without charge in an Egyptian prison for over 50 days until their release last week. Many of you were probably following closely too: filmmakers, scholars and activists including several of our colleagues and friends (such as GQC participant B. Ruby Rich), mounted an impressive campaign to get the men released. From social media networking on Facebook through a Tumblr petition to old-fashioned face-to-face meetings with embassy staff, we’ve been reminded of the strength of feeling and action our communities can sustain. If you’re not familiar with the story, The Guardian’s reports have been one good source of accurate information. So at a basic level, this post is prompted by a desire to celebrate John and Tarek’s safe release.

But there’s a lot else going on in these events; debates and issues that are central to thinking about the political life of queer cinema in the world today. One issue is the reason that we haven’t written anything sooner on Greyson and Loubani: it was crucial to minimise knowledge that Greyson is gay. This Buzzfeed story describes the media strategy that demanded Greyson’s partner Stephen Andrews vanish from the public eye, creating a new closet for the pair.

The duo’s friends and family knew the reporting trip was risky. So they had come up with a strategy ahead of time for exactly this situation, taking into account Egypt’s history of persecuting LGBT individuals. And that plan called for Andrews to become invisible.

He was still the next of kin communicating with the diplomats working on getting Greyson and Loubani released. But his name was absent from media coverage. Greyson’s sister, Cecilia Greyson, was the spokesperson for the family. Activists and friends worked tirelessly to ensure that major news outlets would obscure the fact that Greyson was gay and omit that his queer-themed films were well known in arts and activist circles.

Major news outlets like the Guardian and the New York Times assented to this plan and it seems to have been both necessary and successful. In thinking about queer cinema from a global perspective, we try to overthrow narratives that locate queerness only in the Western imaginary, and there is certainly a media impulse to simplify ideas of Canadian sexual freedom and Egyptian homophobia. And yet, despite the realpolitik of choosing battles and getting them out alive, this story asks us to navigate complexities of identity and disclosure. Egypt has been a cause celebre for international gay politics before, in the Queen Boat case, in which 52 men were arrested on a gay party boat and tried for “debauchery” among other crimes. The relationship of Western gay politics with Egypt has been fraught, but here Greyson’s queerness does not align so neatly with neocolonial visions of Egyptian culture.

Some critics of the campaign to release the men argued that this was typical Western liberalism – that the activists only cared about Western people incarcerated in Egypt and not about all of the Egyptians similarly confined. This accusation raises some key questions for thinking about global cultures, not least about the ethical obligation of the cultural outsider. Supporters of John and Tarek were rebuked for not engaging with the Egyptian coup more broadly, but gay activists after the Queen Boat incident were heavily criticised for stepping in as “white saviours” and making everything worse. The space between speaking with the other and speaking for the other is perilous, and it is surely easier to condemn than to engage. Alexandra Juhasz has written eloquently about the frustrations and limitations of the campaign, and in her blog she reflects on this issue:

But to be honest, there was also something deeply painful, knowing each day, and after every act by which we used all of our highly dispersed and cunningly eccentric cultural capital (and its associated real-world political power) that there were so many others in that very prison, or elsewhere in another prison, who do not and will not ever have such powerful, connected, capable friends and allies; their crimes no more real, their imprisonment no less unjust …

What makes a crucial difference in distinguishing the politics of this situation are Greyson’s own political commitments. The pair were travelling to Gaza, where Loubani worked with Palestinian doctors. Greyson has been a significant figure in the BDS movement: several of his activist videos are available on YouTube, for instance the awesome BDS Bieber. Greyson is a filmmaker for whom queerness and worldliness are interwoven as intimate politics, as visible in the aesthetics of his feature films as in the agitprop video work. My own favourite is Proteus, which subverts the conventions of the heritage film to construct a queer love story in eighteenth-century South Africa. Racist European science, colonial history in Africa, and echoes of Nelson Mandela’s more recent incarceration unfold across aesthetically beautiful images of flowers and bodies. Greyson’s film and video work is already a powerful rebuke to liberalism and an ongoing attempt to rewrite queer identities for a radical vision of what it means to be in the world.

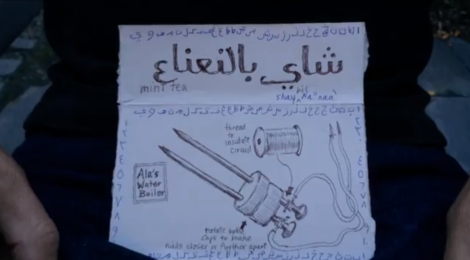

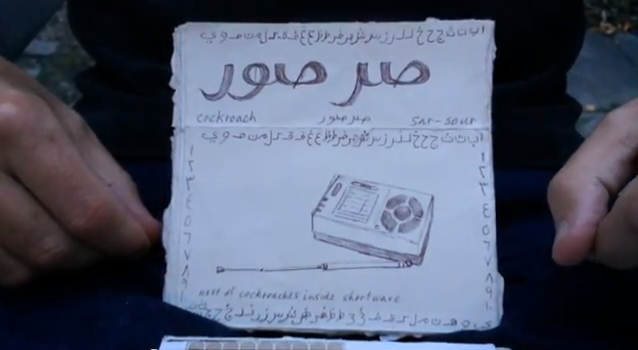

It comes as no surprise, then, unlike the concern trolling of some of his critics, Greyson’s investment in those still jailed in Egypt is intimate and heartfelt. We were excited to see his new video, Prison Arabic in 50 Days, which is dedicated to “the many who spoke out for their release, and for the many who are still behind bars.”

More of Greyson’s videos can be found on Vimeo here. If you want to read more, we recommend this excellent new book, The Perils of Pedagogy: the Works of John Greyson, edited by Brenda Longfellow, Scott MacKenzie and Thomas Waugh.

RSS - Posts

RSS - Posts