Special Dossier on Roma: Watching Roma In Mexico City

by Paul Julian Smith*

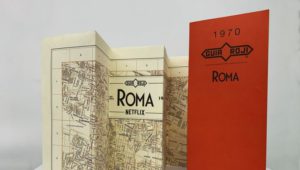

In her interview with Alfonso Cuarón in Letras Libres, Mexico City-based critic Fernanda Solórzano begins by saying that “all conversations lead to Roma.” And it certainly felt like that as I visited the capital where discussion of the film was everywhere. The main focus of Solórzano’s interview is space: she quotes Cuarón as saying that he let “the places dictate what was going to happen.” Proving his point, Solórzano showed me a promotional document sent by Netflix to local critics. It was a simulacrum of the Guía Roji, a guide and map of the period to the city, now defunct. In Netflix’s expertly mimicked version we are directed to places both lost and preserved, such as the long-gone Cine de las Américas (where Cleo is abandoned by her faithless boyfriend during a film screening) and the still-existing fancy Teatro Metropólitan (which she hesitates to enter earlier in the film).

Netflix itself also exploited place in its Mexican promotion of the film. Ubiquitous posters of Roma were placed side by side in the streets with promos for the streaming giant’s new Mexican series Diablero, released on December 21, suggesting a complete convergence of prestige feature film and long form television. Amid much polemic, Roma was shown briefly in select independent theaters: the Cine Tonalá (in the colonia Roma itself), Cinemanía (where Netflix kitted out a theater with special equipment) and the twin film schools of the CCC (Centro de Capacitación Cinematográfica) and the CUEC (Centro Universitario de Educación Cinematográfica) (Cuarón’s Alma mater). An especially poignant show was held at the Auditorio Blackberry, which is built over the demolished Cine de las Américas. Screenings at the public Cineteca Nacional belied the fact that the film was made wholly outside the Mexican institutional context of IMCINE. And viewers angered by the small number of screens blamed the commercial duopoly of Cinemex and Cinépolis for failing to show the film. This was hardly fair. Cinépolis sponsors the Morelia International Film Festival, which had provided the showcase for Roma’s premiere in Mexico (Cuarón appeared alongside the chain’s CEO at the event). And the exhibitor explained in a public statement that the lengthy negotiations with Netflix had broken down when the streamer refused, as in other territories, to respect the three- month window, which by traditional agreement separates theatrical release from distribution on other platforms such as DVD or internet.

I myself saw Roma in a theater on December 18, shortly after it had been made available online. My choice of venue was the Casa del Cine in calle Uruguay in the Historic Center. La Casa del Cine is housed in a small period building and is reached by ascending stairs around a central patio (an arrangement rather similar to that of Cleo’s house in the film). Like Cine Tonalá, it provides a welcoming bar and restaurant for its fashionable clientele, adding social and gastronomic value to the film experience which is enjoyed in its two tiny screening rooms. Roma was programed in number 1, which at a rough count boasts only fifty seats. When I arrived, the line was already snaking around the patio void, which was hung with moody photos of current Mexican indie film stars.

Once inside the theater, which is decorated in true cinephilic style with French posters of American movies, things got a little strange. One patron brought a banjo and harmonica with him. The elderly couple next to me would talk throughout the film, commenting on the accuracy or not of its mise en scène (in spite of my annoyance, I tried to consider this as a contribution to the study of Roma’s reception in Mexico City). The hirsute manager of the theater preceded the film with a lengthy announcement. He told us we were not allowed to get up during the screening and would be blinded if we looked back at the projector, newly installed to meet Netflix’s (or Cuarón’s) requirements. He also warned us that if we so much as took out our phones, an act which would be observed by a monitor present in the screening, the film would stop and we would be ejected from the theater. Intended to prevent piracy, this warning seemed somewhat otiose as Roma was already available on Netflix and, indeed, on pirate DVD sold all over the city (one stall on Insurgentes was papered with multiple copies for 10 pesos apiece). In spite of this rigorous discipline, which served no doubt to enhance the scarcity and value of a rare theatrical screening, the audience responded with lengthy applause at the end.

Roma’s most notable place of screening had come just days earlier when it had been shown outdoors for free in Los Pinos, the official residence just opened to the public by new President Andrés Manuel López Obrador. And watching Cuarón’s film that week in Mexico it coincided inadvertently with three of AMLO’s political initiatives. Thus, the planes that fly over Cleo’s house in the first and last sequences (planes which of course Cleo will never take) reminded me of the President’s cancelation of the new airport in Texcoco, which he alleged would serve only “fifís” (“snobs”). The student demonstration in the film, brutally cut short by neofascist Halcones, reminded me of the stinging cuts to public universities announced in AMLO’s first budget (he soon reversed those cuts, no doubt thinking that mass student activism against him was not a good look at the start of his presidency). Finally, watching a film made outside Mexican publicly funded cinema institutions made me think of AMLO’s budget cuts to the arts, including cinema, which at the time of writing have not been reversed. These cuts attacked one of the new President’s faithful constituencies, Leftist cultural workers. Most visible amongst those protesting against these cuts was actor Daniel Giménez Cacho, long ago the protagonist of Cuarón’s Sólo con tu pareja (1991).

Beyond politics, the force of the film is of course affective. Hardened cinephiles in La Casa del Cine like myself did not hold back their tears in emotional scenes like the one when Cleo lost her baby. And Solórzano, most unusually, begins her piece by telling Cuarón how she recently reunited with her own nanny, only to find (as Cuarón correctly guesses) that her room was hung with framed photos of the child she cared for long ago. Cuarón says that it is with reason that middle class Mexicans have forgotten their debt to the indigenous servants they once claimed to love so much. It is Roma’s achievement, then, to have retrieved those memories by allowing hallowed places of a shared past to dictate the action of the film, even at a time when the theatrical experience of cinema and the very definition of a feature film is so clearly under threat, in Mexico and beyond.

*Paul Julian Smith, FBA, is Distinguished Professor, Ph.D. Programs in Latin American, Iberian, and Latino Cultures and Comparative Literature Graduate Center, CUNY. He is the author of 20 book and 100 articles. His most recent books are Queer Mexico: Cinema and Television Since 2000; and Television Drama in Spain and Latin America

https://www.sas.ac.uk/publication/television-drama-spain-and-latin-america-genre-and-format-translation

Follow him on Twitter: https://twitter.com/#!/pauljuliansmith