Celebrating the Work of Eduardo Coutinho (1933-2014)

Last update July 14, 2014

‘What differentiates me from many directors is that I don’t make films about others, but with others’

Eduardo Coutinho

Today, Mediático celebrates the work of one of the most important Latin American filmmakers, the Brazilian documentarist Eduardo Coutinho. Coutinho died in tragic circumstances on February 2, 2014. We are very grateful to be able to present an essay in his honour by Cecilia Sayad, Lecturer in Film Studies at the University of Kent, UK, and a co-director of the Centre for the Interdisciplinary Study of Film and the Moving Image. Dr Sayad is the author of Performing Authorship: Self-inscription and Corporeality in the Cinema (I.B. Tauris, 2013), which has a chapter on Coutinho, and she is co-editor, with Mattias Frey, of the forthcoming Film Studies journal, to be re-launched in 2015 (Manchester University Press). Mediático is also grateful to Michael Chanan, Adrian Martin, Tiago de Luca and Lúcia Nagib who each provided a number of further links and material for this tribute, joining those collected by Mediático co-editor Catherine Grant.

Eduardo Coutinho’s Films Were About Gaps and Creative Frictions

Cecilia Sayad

When announcing Eduardo Coutinho’s tragic death, Brazilian newspaper O Estado de S. Paulo reported that the director had recently revisited the place and the subjects he interviewed in Twenty Years Later (Cabra Marcado para Morrer, 1984) to film a bonus feature for the long overdue DVD release of his most acclaimed documentary.[1. Roberta Pennafort, ‘Cineasta Eduardo Coutinho é assassinado a facadas no Rio’, O Estado de S. Paulo, 2 February 2014, accessed 3 February 2014, http://www.estadao.com.br/noticias/arte-e-lazer,cineasta-eduardo-coutinho-e-assassinado-a-facadas-no-rio,1125918,0.htm; Guilherme Genestreti and Juliana Gragnani, ‘Eduardo Coutinho deixou inacabado filme sobre adolescentes,’ Folha de S. Paulo, 4 February 2014, accessed 4 February 2014, http://www1.folha.uol.com.br/ilustrada/2014/02/1406967-coutinho-deixa-filme-sobre-adolescentes.shtml.] Twenty Years Later is itself about going back—in that case, to trace the fate of a fiction film (Cabra) aborted by the 1964 military coup in Brazil, as well as to reconnect with the militant peasants of the state of Paraíba who, in neorealist fashion, would have enacted a fictional version of their own struggles.

In his obituary for Coutinho, critic Inácio Araújo stated that Twenty Years Later might have been about the peasant movement, the military coup, political persecutions and fear. “But above all,” says Araújo, when Coutinho went back to Paraíba in 1982 he made “a film about time: about the 18 years that separated the two shoots. With this, he introduced also what would be an essential element in his filmography: fiction.”[2. Inácio Araújo, ‘Análise: Mestre absoluto, cineasta ainda poderia chegar muito longe,’ Folha de S. Paulo, 3 February 2014, accessed 3 February 2014, http://www1.folha.uol.com.br/cotidiano/2014/02/1406648-analise-mestre-absoluto-cineasta-ainda-poderia-chegar-muito-longe.shtml. Translation Sayad’s.]

The temporal gap between a lived experience and its account is indeed integral to any documentary film; fiction, here, is precisely the inevitable artificiality that comes into the organisation of past events in a narrative. But the most illuminating element of Araújo’s argument lies in the emphasis on time as the encounter between present and past experiences, as a tension which allows for the fiction to take over—not to replace a presumed truth, but on the contrary, to bring us a little closer to it. The key to his oeuvre is thus the idea of an encounter—the retrospective of the director’s work at Centro Cultural Banco do Brasil in 2003 was aptly titled ‘O Cinema do Encontro.’

This encounter produces a creative friction that is indeed the main topic of Coutinho’s documentaries. It is present, for example, in the tension between the subjects’ experiences and their narration of them—in the tension between fact and fiction. Coutinho’s decision to reveal a young woman’s admittance to lying in Edificio Master (2002)—‘I’m a truthful liar; I lie but I say the truth’—puts faith in the potential that the performance to a camera has to elicit other ‘truths’: especially those concerning the very making of a documentary film. The discrepancy between an experience and its narration was more radically explored in Playing (Jogo de Cena, 2007). Shot on an empty stage, Playing juxtaposes real testimonies given by the subjects who experienced them with the reproduction of their speeches by professional actors—some of whom were unknown to audiences, preventing the discrimination between ‘real’ and ‘performed,’ thus making a statement about the very futility of discerning between the two. Coutinho’s documentaries do not only have an element of fiction, as all documentaries do—they are about fiction, just as they are about documentary filmmaking. The Mighty Spirit (Santo Forte, 1999) is as concerned with the religious and mystical experiences relayed to the camera as it is with the ways in which both the director and the apparatus shape these testimonies—or the subjects’ performances.

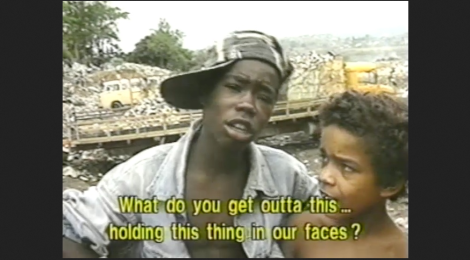

To be sure, Coutinho was averse to reenactments—he referred to them as ‘impure images.’[3. Consuelo Lins, O Documentário de Eduardo Coutinho (Rio de Janeiro: Jorge Zahar, 2004), 116.] Performance, here, is restrained by the structure of the talking-head interview shot straight on, and usually framed in medium close-ups. (Even when subjects sing in As Canções, 2011, they for the most part do it while sitting on a chair.) Coutinho’s presence is certainly a catalyst, but it is as self-effacing as the performances it ignites, reduced as they are to the verbal expression. In the theatrically released documentaries that followed The Mighty Spirit the director refrains from voicing his own views, from analysing, interpreting or judging what we see. His questions to the subjects are very open and simple, asking them about their origin, work, civil status or children. The intended mundaneness of his queries suggests that the uniqueness of the interview must lie with the documentary subject, not maker—but it would be more accurate to say that it lies with the encounter between the two. It is Coutinho’s presence that propels the tensions that his films document—a woman from the slams humorously asking, ‘Do you want poverty?’ in Babilônia 2000 (2001) when Coutinho’s crew stops her from putting on lipstick; or a resident of the apartment building in Edifício Master (2002) diplomatically admitting that Copacabana is ‘anthropologically’ interesting for its mixed quality (presuming Coutinho’s fascination for that Rio neighborhood), while the exasperation that surfaces in her comments on the bustling streets implies the impracticalities of living in an area that for outsiders may seem excitingly exotic. Coutinho’s presence in the image highlights the sociocultural gap and produces the friction between subject and filmmaker that his documentaries are all about.

2014 marks the 50th anniversary of the coup that interrupted the making of Cabra and the 30th of the historical documentary that came out of that abrupt ending—albeit twenty years later, as the English title suggests. But this anniversary is all the more significant because it leaves us with yet another production brought to a halt—Coutinho had a documentary about public school teenage students underway when he died. Film editor and longtime contributor Jordana Berg told Folha de S. Paulo that the director had agreed to open the film with a scene in which he tells an interviewee that the documentary is probably not going to work out.[4. Genestreti and Gragnani, ibid.] It is too soon to know whether we will see a posthumous release. Never seeing it might confirm Coutinho’s skeptical prediction, leaving the unfinished film to the fate that Cabra was rescued from. Seeing the footage in any form would bring Coutinho’s career full circle, adding a new term to his repertory of creative frictions by juxtaposing what a film is with our idea of what it would have been.

Other tributes to Coutinho:

Online interviews/articles by Eduardo Coutinho:

- ‘Santo Forte: a entrevista no cinema de Eduardo Coutinho’, DOC On-line: Revista Digital de Cinema Documentário, Nº. 7, 2009 , págs. 130-132, with Giovana Scareli

- ‘O documentário como encontro: entrevista com o cineasta Eduardo Coutinho’, Galáxia, 6, 2003, with A Figueirôa, C Bezerra, Y Fechine

- ‘Os dois lados da câmera’, Batuques, fragmentações e fluxos, 2000

- ‘O cinema documentário ea escuta sensível da alteridade,’ Projeto História. Revista do Programa de Estudos Pós-Graduados de História, v. 15, 1997

- ‘Cabra marcado pra morrer’, Lua Nova: Revista de Cultura e Política, 1984

Additional Bibliography on the Work of Eduardo Coutinho:

- Maria Sílvia Antunes Furtado, ‘FICÇÃO E SUBJETIVIDADE NO DOCUMENTÁRIO DE EDUARDO COUTINHO’, Anuário de Literatura, vol. 17, n. 1, 2012

- Lorena Cancela, ‘Sobre Juego de escena de Eduardo Coutinho’ Páginas del diario de Satán, March 9, 2008

- Michael Chanan, ‘Eduardo Coutinho and the spirit of documentary’, First published in Guaraguao, No.22, 2006

- Juan Ciucci, ‘La vida en la basura, [Boca de Lixo, 1993]’, Tierra en Trance: Reflexiones sobre cine latinoamericao, November 2013

- Verônica Dias Gonçalves, ‘A Cinema of Conversation – Eduardo Coutinho’s Santo Forte and Babilônia 2000’, in Lúcia Nagib (ed), The New Brazilian Cinema. London/New York: IB Tauris, 2003

- David William Foster, ‘Metafilmic Devices in Eduardo Coutinho’s Boca de Lixo’, Revista Cientifica, v.4, n.2 p.155-165, jul./dez. 2009

- Pablo Gonçalo Martins, ‘The Subjective Turn in Brazilian Doumentaries’, Paper at LASA Conference, 2012

- Karla Holanda, ‘Documentário brasileiro contemporâneo e microhistória’, Fenix – Revista de História e Estudos Culturais, 2004

- Suzy Lagazzi, ‘The social in scene in significant materiality’, Acta Scientiarum. Language and Culture, vol. 32, núm. 2, 2010, pp. 153-161

- Consuelo Lins, (2007) ‘The cinema of Eduardo Coutinho,’ Studies in Documentary Film Volume 1 Number 3

- Fernão Ramos, (2014 – forthcoming) ‘Mise-en-scène in documentaries: Eduardo Coutinho and João Moreira Salles,’ Studies in Documentary Film 8.2

- Cecilia Sayad, (2006). ‘Authorship in the Interstices of History, Biography, Reality and Memory: Histoire(s) du cinéma and Cabra Marcado para Morrer’. Significação: Revista Brasileira de Semiótica 26, pp. 139-172

- Cecilia Sayad, (2010) ‘Flesh for the Author: Filmic Presence in the Documentaries of Eduardo Coutinho’, Framework, 51.1

- Gustavo Soranz Gonçalves, ‘Panorama do documentário no Brasil’, Doc On-line, n. 01 Dezembro 2006

- Eduardo Valente, ‘Moscou, de Eduardo Coutinho (Brasil, 2009)’, Cinética, April 2009

- Ismail Xavier, ‘Ways of Listening in a Visual Medium – The Documentary Movement in Brazil’, New Left Review 73, Jan-Feb 2012

Further Links

- NEW 18 Filmes de Eduardo Coutinho (link via Mark Cousins) http://www.revistabrasileiros.com.br/2014/02/07/18-filmes-de-eduardo-coutinho/

- On Coutinho’s Top 5 films: http://www.faroisdocinema.com.br/2010/08/farois-eduardo-coutinho/

- Boca de Lixo opening sequence: http://youtu.be/zRGCB7uTCUo

- Edificio Master – The Stammerer: http://youtu.be/zZ46Q95Iz5s

- Five documentaries by Eduardo Coutinho: http://www.pragmatismopolitico.com.br/2014/02/assista-5-documentarios-de-eduardo-coutinho.html

Notes to Cecilia Sayad’s essay

[…] Chanan, Professor of Film and Video at Roehampton University, London. This work complements Mediático’s earlier published tribute to Coutinho, headed by a written study of his work by Cecilia […]

Hola! I’ve been following your website for a while now and finally got the

bravery to go ahead and give you a shout out from Humble Texas!

Just wanted to say keep up the great job!