The International Film Festival Rotterdam: Focus on Latin America

Mediático is delighted to present the following report on Latin American cinematic offerings at this year’s Rotterdam Film Festival by first-time attendee Deborah Shaw, Reader in Film and Television Studies at the University of Portsmouth and founding co-editor of the journal Transnational Cinemas. Shaw is author of The Three Amigos: The Transnational Filmmaking of Guillermo del Toro, Alejandro González Iñárritu, and Alfonso Cuarón (Manchester University Press, 2013); Contemporary Latin American Cinema: Ten Key Films (Continuum Publishers, 2003). She is also editor of Contemporary Latin American Cinema: Breaking into the Global Market (Rowman and Littlefield, 2007). She is currently working on establishing a research network on Cinema Funding Bodies and Global Arts Cinema.

Educational Panels at Rotterdam

Hubert Bals, the first director of the Rotterdam Film Festival, which began in 1972, claimed that he wanted at least a third of the festival to be dedicated to debates and discussions with experts. This principle was very much in evidence at this year’s festival with a full session of ‘Expert Panels’. I attended various sessions, including one ostensibly on ‘artistic directors in an age of changing perceptions, pressures and pursuits’, but that ended up being a discussion on festivals by experienced festival directors Hans Hurch, Marco Müller, Frederic Boyer, Tine Fischer, Chris Fujiwara and Nashen Moodley, and chaired by Madeleine Molyneaux.

For an academic used to papers informed by the latest theoretical frameworks, it was fascinating to hear the shared experiences of these eminent figures and learn about their real world stories. Yet, that didn’t mean that these directors were not grappling with big intellectual issues. Much of the debate focused on ways in which festivals could maintain the classical ideal of internationalism as a virtue in itself (Fujiwara) when festivals are bigger and more business oriented than ever. Nashen Moodley asked the central question facing festival directors: how do directors keep their artistic vision while dealing with economic pressures?

With on average 120 feature films, a large number of short films and a selection of retrospectives, festivals are enormous beasts. The size of festivals was also raised as an issue, and one gripe of Frederic Boyer was that international critics are not interested in reviewing small art house films, which can disappear in the mass of films shown. All the panel members stressed the importance of building close links with the cities that host them, and Tine Fischer, director of the Copenhagen documentary film festival (CPH:DOX) claimed that this is what she was most proud of achieving. This link between community and festival was certainly in evidence in central Rotterdam where the festival’s proud tiger logo was everywhere to be seen. The film culture in the city is vibrant and there are many well attended cinemas dotted around, many with cafés selling freshly prepared food (great soups and quiches).

All the festival directors highlighted the need to develop personal relationships with producers and film directors, and they told a number of anecdotes about how schmoozing had resulted in their festival securing a coveted première. The theme of personal relationships, and the transferable skill of being nice to people, was also raised in another panel, ‘Get your film noticed and reach an audience’. This well-attended session comprised a panel made up of people who knew just how to do this and were keen to share their advice. It was hosted by Wendy Mitchell (Screen International Editor), and included Kathleen McInnis (Festival strategist), Laurin Dietrich (Wolf Consultants), Liz Rosenthal (Power to the Pixel, and Thessa Mooji (Silversalt PR).

As an academic new to the festival circuit, it was stimulating to gain an insight into the ‘applied’ world of filmmaking. The recurrent word was ‘strategy’ and all the panellists highlighted the need to: have quality images and stills for promotion; choose the right festival for exposure (a small festival such as Locarno and Toronto can be better for a smaller film); spend time with your film after it is made to promote it (Joshua Oppenheimer’s The Act of Killing was cited as the model example of this); network with people at festivals; use social media to promote your film, but be careful of putting your film online as it will prevent festival exhibition, awards eligibility and sales. One member of the panel made people laugh when she advised the press agents to tell the critics that they loved what they wrote and then to make sure to find out what it was that they wrote later. These are the approaches and stories that many academics often don’t know about, as we tend to teach or write about a film without worrying too much how that film made the difficult journey to theatrical release, DVD or VOD.

I also attended sessions run by the Hubert Bals Fund offering advice on applying to the Dutch funding body, and a dry but informative session explaining the EU cultural programme and the shift from MEDIA Mundus to Creative Europe (the international dimension of European support to the film industry).

The films

There was a good selection of Latin American films showing at this year’s festival, including the Argentine Tres D, by Rosendo Ruiz, the Mexican Las voces/The Voices by Carlos Armelia, the Mexican Los insólitos peces gato/The Amazing Catfish by Claudia Sainte-Luce, El lugar del hijo/The Militant by the Uruguayan Manolo Nieto, Por las plumas/All About the Feathers by Neto Villalobos from Costa Rica, the Argentine El día trajo la oscuridad/Darkness by Day by Martín Desalvo, Reimon by the Argentine Rodrigo Moreno, co-produced with Germany, the Brazilian La casa grande directed by Fellipe Barbosa, Hotel Nueva Isla a Cuban-Spanish co-production by Irene Gutiérrez, and the best known of the selection, the award winning Heli by the Mexican Amat Escalante.

Unfortunately, as I was only attending for two days due to commitments in my day job at the University of Portsmouth, I could only see a sample of this treasure chest. The first film I saw was the Brazilian La casa grande (Fellipe Barbosa, 2014). This was a tender film that, in the vein of many recent Latin American festival films, explored class, ethnic and gender relations through a focus on a single family and a single house using a middle class POV (La ciénaga, Martel, 2001, Post Tenebras Lux, Reygadas, 2012). The semi-autobiographical scenario, co-authored by director Barbosa, tells the story of Jean, an upper middle class, white teenager who attends a private school. His father has serious money problems brought on by his own corruption and incompetence. Despite their best attempts to ignore their personal financial crisis, the privilege of the family is called into question through their inability to keep up the payments for their affluent lifestyle, symbolised by the big gated house (la casa grande) in which they live.

The film raises some interesting questions about contemporary Brazil through Jean’s relationship with his black chauffeur, and his working class, dark-skinned girlfriend, like Jean, preparing to go to University thanks to a quota system designed to help black and mixed race students. (http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/world/americas/8285350.stm). There is criticism of the world of white elitism running throughout, seen most directly in the fact that Jean is happiest when with his family’s black and mixed race staff, and when he is with his girlfriend. According to the director: “It’s a very personal, character driven story which also deals with a lot of issues touching Brazil today from Brazil’s legalisation of affirmative action last year to the fact that the country’s wealthy classes feel uneasy about their wealth. They don’t talk about it.” Above all, this is a tender, warm film, and while we may laugh at Jean’s teenage awkwardness, and moody outbursts against his father, we always care about him and his affairs of the heart. I came out of the cinema smiling stupidly.

Jean in Casa Grande played by Thales Cavalcanti

I went to see the world première of Las voces/The voices (2014) after a chance meeting with the film’s first-time producer Yadira Aedo and director Carlos Armella over coffee during a break. Carlos worked with Alejandro González Iñárritu on Babel (2006) and directed the ‘making of’ film available on the DVD, and Iñárritu was Las voces’ executive producer. Carlos also co-directed the documentary Toro Negro. Las voces was supported by the Hubert Bals fund which helps to explain its presence at the IFFR.

The film is beautifully shot, intellectually stimulating and an original meditation on the relationship between the filmmaker and his subject. It initially appears to be a straightforward documentary. Sebastián, a young documentary filmmaker, moves into the house of his two subjects, an elderly man, Jesús Vallejo and his youngest son Juan Diego. La Estancia is an abandoned village whose inhabitants have left for el norte (the US), or DF (Mexico City) when the only source of employment, the local mine, goes out of business. This leaves only Jesús and Juan Diego living an isolated but contented existence enjoying the bounty of the land. Jesús lives with his memories and the title refers to the voices he hears of those who are now gone.

The modern city dweller filmmaker Sebastián turns his anthropological eye on the ‘backward’ subjects of his study, and while he appears to live on equal terms with them and treat them with respect, inequality is intrinsic to their relationship. The expectation is that Sebastián will make his film, maybe win a few awards, and never see Jesús and Juan Diego again. His subjects, on the other hand will not leave La Estancia as Jesús is too old to make a new life, and Juan Diego is committed to caring for his father. Nonetheless, Carlos Armella presents a twist on the expected trajectory of the film. The documentary is never finished and Sebastián returns some unspecified time later with his very pregnant girlfriend and, finding the village empty, takes shelter in the family home. Juan Diego also returns and, grieving for his dead father, takes shelter in the local church.

I won’t reveal more of the plot as this would result in spoilers, but the remaining part of the film offers an analysis of the relationship between filmmaker and subject as documentary merges with fiction, and the boundaries between the two forms become unclear. Ultimately viewers are left with many questions. Can Juan Diego, the subject of the unfinished documentary, become the director of his own film and turn Sebastián into his subject? Who/what remains after a film is finished? Can the viewer discern fantasy from reality and whose fantasy governs the narrative? As with Carlos Reygadas’s Post Tenebras Lux the subject matter of the film is the encounter of the Euro-Mexican with the indigenous Mexican and how this reflects the cultural differences and power dynamics within the country.

The film also resembles, like so much Mexican culture, Juan Rulfo’s classic novel, Pedro Páramo: the abandoned rural villages in the novel and the film are full of the voices of the dead and the departed, but, in contrast to Rulfo’s novel, Carlos Armella’s abandoned pueblo is no hell. Rather, the rural Mexico seen in Las voces is a form of earthly paradise that city dwellers have turned their backs on.

Jesús Vallejo in Las voces.

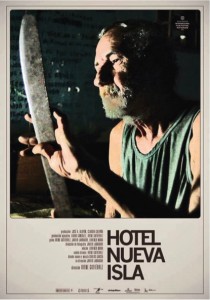

Hotel Nueva Isla (Irene Gutiérrez), another film that saw its première at Rotterdam, fits within the art cinema category of “slow cinema”; it was so slow that many left the auditorium, which was surprising given it was a largely cinephile audience. It received funding from Cinergia, the Central American fund supported in part by the Dutch cultural programme Hivos, as well as Ibermedia, the Spain dominated Hispanic film fund, Spain’s Instituto de Cinematografía y de las Artes Audiovisuales (ICAA), and the Sundance Institute. Given such a funding structure, Hotel Nueva Isla had the label “festival film” stamped all over it along with all the pleasures and challenges that this kind of cinema brings with it. The number of static takes of the protagonist, Jorge, and the rubble-strewn hotel make clear demands on the spectator which not everyone in the audience relished. Perhaps the audience members who left also felt disappointed because the Cuba implicitly promised to them in the titular references to ‘island and new hotel’ is never revealed in the film. There are almost no exterior shots, no blue skies, no images of Havana’s iconic seawall (the malecón), and no sensual imagery of the beautiful people of Cuba. Instead the film focuses on the dilapidated hotel of the title and the aged body of Jorge, a retired state worker, who painstakingly dismantles the hotel with very basic tools in search of items of value left behind by the previous owners before the revolution. The film speaks of solitude, neglect, and abandon.

As with Las voces, the central character is a man who has been left alone by his children and, like Jesús, he does not know where they are (they could be in Camagüey or in the US). Yet, whilst in La Estancia the earth provides its natural treasures in the form of fruit and vegetables, the hotel yields very little; a cake slicer and a worthless old spoon is all Jorge finds. He has passing relationships with the people who have found a temporary home in the hotel, but they inevitably leave. There is beauty in this tender, photographic portrait of decay, but it is, again, only for the patient viewer. This type of slow cinema manages to secure funding, but can it secure an audience?

Amat Escalante’s Heli, for which he won best director at Cannes 2013, was an altogether different experience. It was shown to a packed audience, and was a visceral, hard, but rewarding watch (I had to take off my glasses for the torture scene, one of the benefits of myopia). Heli tells the story of the eponymous young car factory worker who lives with his wife, son, father and sister. There is nothing extraordinary about the family as the visiting census gatherer establishes in the first few minutes.

The film manages to combine the art cinema pleasures of watching ordinary families in another country go about their daily lives and loves, with the drama of a thriller as Heli inadvertently gets involved in corruption and violence. It also combines tender domestic scenes, with (short) scenes of extreme brutality. The film offers no answers, but presents a snapshot of violence in all its powerful sadistic absurdity. The picture it offers of Mexico is one of corruption and incompetence at official levels, with an Army official organising drug trafficking and violent reprisals for anyone who goes against him, and Detective Maribel more interested in showing Heli her breasts than in solving the case of his missing sister. Nonetheless it also presents an intimate picture of family love, and ordinary people entirely at the mercy of fate.

Estela played by Andrea Vergara in Heli.

I have certainly caught the film festival bug, and hopefully this will be the first of many visits.

You have piqued my interest in the Latin American films you viewed at the festival. I will keep an eye open for them and do my best to attend when they show up on screen in NYC.