BRASSROOTS DEMOCRACY: MAROON ECOLOGIES AND THE JAZZ COMMONS

A Book Presentation By Benjamin Barson delivered at the University of Sussex on 17 October 2024

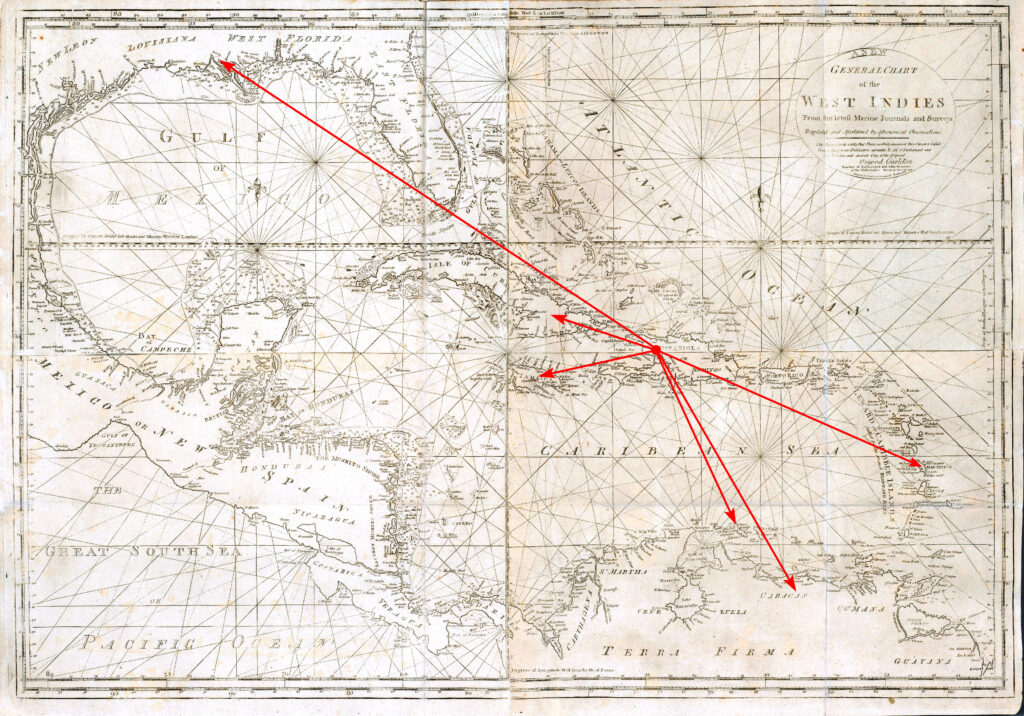

In my recently published work Brassroots Democracy: Maroon Ecologies and the Jazz Commons (Wesleyan University Press, 2024) I consider the Haitian Revolution, following Martin Munro, as a musical event that transformed the rhythmic and sonic lexicon of the Americas—and in particular, New Orleans.1 I make this argument through tracing the musical components of what Julius Scott calls The Common Wind. Scott makes evident a transatlantic informational pipeline through which mobile peoples in the African diaspora—maroons, free Black sailors, and Black women merchants—connected Afro-American communities across the Atlantic world to a shared struggle in the age of the Haitian Revolution. Building on Julius Scott’s insight that rumor, song, and itinerant speech stitched the Black Atlantic into a counter-infrastructure, I treat sound itself as the medium of political transmission. Music both illustrated and circulated revolt—an acoustic traffic of chants, horn calls, and work-song cadences that ferried knowledge across docks and plantations.2 The musical maroons that Scott named “plantation dissidents” remind us that meaning accumulated through motion, as every repetition risked punishment but also deepened a poetic politics of relation.3 The clandestine networks Scott mapped can be heard as a proto-musical commons, a system of communication whose grammar was rhythm, timbre, and imagination rather than paper, ink, or ownership.4

Some of the questions I tried to answer in my book came about through an audio-imaginative exercise in deep listening: how to hear the music in this rhizomatic informational network. How did song and sound shape and make the common wind? What changed meaning through aural ephemera’s travel and adaptation? Was this wave of creolization necessarily a politicized process, and would it always bear ideological markers?

Before focusing on the Crescent City, I want zoom out to see (or, rather, hear) a panorama of documented songs throughout the Caribbean. Making evident what Sara Johnson has called the “Fear of French Negroes,”5 in Venezuela in 1801, a colonial administrator complained: “There is going around quite openly among the freemen and slaves of the hill country news of the capture of the Spanish island of Santo Domingo by the Negro Toussaint, and . . . they display great rejoicing and merriment at the news, using the chorus ‘Look to the firebrand [tisón],’ as a response to the words ‘They’d better watch out!’6

In Martinique and Guadeloupe in 1803, according to alarmed planters, a cadre of revolutionary instigators under the banner of Dessalines were sent to incite a slave revolt. They were discovered, apparently, due to their use of song to signal their intentions across the plantation hinterland. According to one frightened planter: “Vive Dessalines!”7

Almost every island was affected by this music of the common wind. The Dutch colony of Curaçao, which housed unruly enslaved prisoners from Saint-Domingue, Cuba, Jamaica, and Brazil in the late eighteenth century, was home to a one-thousand-strong rebellion in 1795. It was co-led by an enslaved Curaçaoan man, Tula, and a Haitian prisoner, Louis Mercier. Mercier, along with other imprisoned Saint-Domingue rebels, had shared news of the revolution’s success. Tula changed his name to Rigaud during the revolt to invoke the Haitian General of the same name. The uprising was defeated after one month, and its leaders were executed, but their names were immortalized in the song “Rebeldia Na Bandabou,” an insurgent anthem still performed by Afro-Curaçaoan Tambú artists today.8

What moved through these songs was a politics of relation as much as a melody.9 Their travel produced an improvised commons—a mobile workshop of rhythm and thought in which people tested new forms of belonging against slavery’s radical variant of social death. Re-metering a European dance or translating a French verse into Creole were acts of theory: experiments in modernity conducted by the dispossessed. The so-called cinquillo complex10 that emerged from this circulation signaled both musical innovation and historical self-recognition, sounding out a modernity conceived in motion, with profound implications for the sociopolitical structures of feeling for each Gulf entrepôt where it was performed.

No city rendered this sonic current more audibly than New Orleans, the Gulf’s northern outpost of the Caribbean world.11 There, the aftershocks of Haiti’s revolution reverberated through processions, dances, and barrooms, all while the city’s population doubled from Saint-Domingue migration during the tumultuous years of 1791-1810.12 To follow these echoes is to hear how a French and Spanish backwater became, simultaneously, an American colony and a Caribbean entrepôt, as the port’s mingled accents and sonic vocabularies converted displacement into a pan-African art.

Music as Marronage

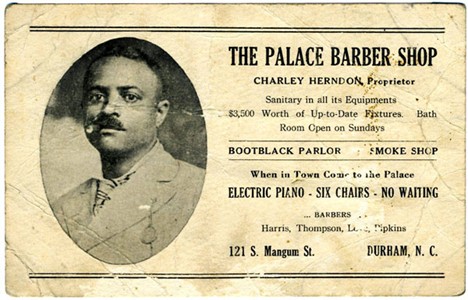

Historian Rashuanna Johnson, in Slavery’s Metropolis, alerts us to an 1810 “wanted” poster for a Haitian-born maroon named Pierre who had escaped to New Orleans. The ad, purchased by a slaveowner seeking to reclaim Pierre’s body, described him as barber who carried “a Tambarine [sic] unstrung in his hand and a razer, from which it is presumed he plays on it.” He had learned how to drum in Saint-Domingue, an example Afro-Atlantic performative culture on the loose in antebellum New Orleans.13

The example of Pierre demonstrates offers one example of New Orleans as home to fugitive music, producing temporary refuge and inspiration for performers and listeners as the culture of the common wind took root. Pierre’s occupation as a New Orleans barber is an important detail, for as don Simon Rodriguez observed in Caracas in 1794, barbershops became revolutionary schools where Black and mulatto youth were educated by “improvised teachers” who taught their students how to “read and comb hair, write and shave” at the same time.14 Such improvised teachers also improvised a dynamic curriculum rooted in principles of popular education, musician-artisan-refugees such as Pierre found an audience to share songs and ideas from the Haitian Revolution and the greater Caribbean. Memoirs produced by Black barbers mention how stories of the Haitian Revolution, Mexico’s abolition of slavery, and the Underground Railroad were all discussed or sung alongside guitar and other instruments.15 “[R]evolutionary songs performed in an overcrowded barbershop”, writes Christina Soriano in her study of Afro-Venezuelan anticolonial activists, “were far more important than any French or American revolutionary text.”16 The imbrication of barber shops with the radical possibility promised by the Haitian Revolution—W. E. B. Du Bois’s father, Alfred, was a barber from Haiti—connected style and substance, aesthetics and ethics, and these semi-autonomous spaces continued to have a lasting impact on Black life in New Orleans.17 As Donald Marquis notes, barbershops were important incubators of New Orleans’ Black vernacular culture through the 1890s, as spaces for young jazz musicians like Buddy Bolden to seek out both musical knowledge and performance opportunities.18 This underground musical culture had roots in spaces that maroon musicians, like Pierre, cultivated as part of the sonic common wind. All these encounters, informed by the Haitian Revolution and the democratic, interdisciplinary culture it contributed to, became inscribed on the improvisatory moment—the musical unmaking and remaking of the world.19

Taking a step back from barbershops and the transnational Black musical underground that it nurtured, I want to focus on why Pierre may have gone to New Orleans. Here, it may seem odd that an enslaved person would seek to escape to the slave market of the Deep South instead of to points North. But Pierre was one of many free Blacks who travelled through the Crescent City. The ability of urban enslaved people to “self-rent” in Saint-Domingue was a practice that migrants from the French colony brought to New Orleans, changing the culture of Black New Orleans and creating more opportunities for self-purchase and a Black underground to develop.20 Maroons like Pierre took advantage of this system, evidenced by an 1810 law which to sought to “prevent Negroes . . . from hiring themselves, when they are runaways.” In 1804, a petition to the city council complained that “fugitive slaves are gathered around the city, which makes our own slaves receivers of their stolen goods, that our slaves provide them with food and ammunition.”21 In addition to barber shops, clandestine information and taverns hosted dances whose participants included hundreds of free people of color and enslaved Africans. Reaching a critical mass at the end of the 18th century, Louisiana’s Spanish colonial government took note; one official complained that the balls of wine merchant Bernado Coquet were “the place where the majority of slaves in this city gather,” while a white Louisianan complained that the enslaved “prolong[ed] their dances and games long after sunset.”22 Tambourinists like Pierre would have been welcome.

In archival research that Henry, myself, and historian John Bardes have undertaken for the last year, we have found considerable evidence of Saint-Dominguean migrant musicians performing with these maroons and fugitive enslaved musicians in swamps, taverns, and various parts of the Black underground in nineteenth century New Orleans. These jam sessions continued well into the Antebellum period. For instance, one enslaver wrote in an 1850 runaway slave ad that Austin Fox, an enslaved dockworker, had escaped his grasp because he “played the fiddle and was to be found in the cabarets.”23

Indeed, this music was threatening to the Louisiana state because it challenged the plantation hold over the Black body, threatening both profit and social control. In July 1806, Louisiana Governor William C. C. Claiborne complained that “Negroes and free people of color were licensed as inn keepers, and …their houses were resorted to by slaves who passed most of their nights in dancing and drinking to their own injury and the loss of service to their masters.”24

What colonial officials heard as dangerous disorder would, in time, crystallize into the very idioms of creolized soundscapes. According to piano reductions that reimagine these musical forms in a salon context, the habanera and cinquillo which Haitian musicians like Pierre were versed in, became omnipresent. African American musicologist Maud-Cuney Hare, who compiled Creole folks songs in the 1920s, tells us that one Afro-Creole folk song – Dialogue d’Amour – may have migrated from the “West Indies.”25 The same rhythmic substructure is apparent.

Here is a video of a performance that I orchestrated of this piece, with Pittsburgh-based Haitian-American singer Chantal Jospeh. This piece is arranged by Alec Zander Redd, who takes an alto saxophone solo.

So-called “folk” songs such as Dialogue D’Amour, which narrated the burning of sugarcane over a habanera ostinato, saw their rhythmic and lyrical insurgencies become commonplace in the work of early jazz musicians. This was especially true of musicians of Haitian descent, including Mamie Desdunes. In Desdnues’s work, this rhythm appears in pieces such as “Mamie’s Blues,” later recorded by her student Jelly Roll Morton. The piece can be heard as a commentary on the dystopian sexual relations of plantation society—translated into the context of the Jim Crow epoch. Written during the mid 1890s and performed widely by the city’s Black artists—it was, according to Buddy Bolden’s trombonist Willie Cornish, a blues that “you had to know”26 if you hoped to become a professional musician—this early blues is marked by its frequent use of habanera and tresillo-inflected bass lines. These aesthetic connections embodied a Black Atlantic linage: Mamie Desdunes was the daughter of Haitian-descended activist Rodolphe Desdunes, who was one of the main organizers of several sit-in campaigns on segregated train cars in the 1890s. Her uncle, Emilie Desdunes, was an ambassador for Haiti to the United States and encouraged Black emigration there.27 Members of the Desdunes family were actively connected to their Haitian heritage and its example as a decolonial, maroon nation. Much like the cypher of clandestine Haitian song that circulated the earlier part of the nineteenth-century Caribbean, there own affiliation with Haiti would be reembodied in musical counterpoint.

Mamie’s Blues is also important for its subject matter. This song viscerally depicts the violence of capitalism in early 20th century New Orleans, where most jazz musicians worked in a gentrified red-light district called “Storyville.” This was a thriving prostitution market, sanctioned by the city, funded by major banks, and marketed in the city’s promotional materials to Northern and European tourists. “219 took my baby away” may have depicted how sex workers were trafficked from New Orleans to Texas Gulf oil boom towns as a metaphor for the lost promises of emancipation. In this sense, it is also a comment on the counter-revolution that had destroyed Reconstruction’s radical promise, which laid the material conditions for this form of sex work to become more commonplace amongst Black rural-urban migrants. Here is a performance of this song with Pittsburgh-based singer Ayana Jones. The arrangement is my own.

Brassroots Democracy

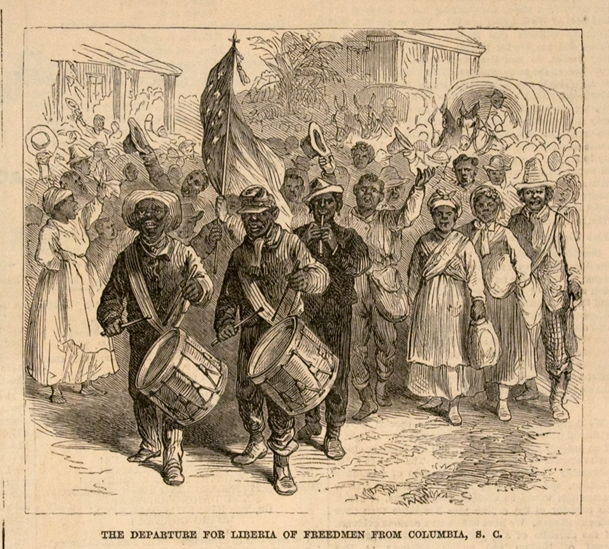

Thus far, we have considered the musical elements of this network of clandestine exchange and their resonances across the nineteenth century. Such considerations lead to a logical follow-up question: did maroons from Saint-Domingue/Haiti and the United States South transmit ideas and cultural technologies that extended beyond music? Did Haiti’s example as what Johnhenry Gonzales calls a “maroon nation,”28 with a relatively self-sufficient rural populace who had mastered the art of not being governed, inspire similar models for post-plantation futurities?

Here it is should be noted that, in the aftermath of the Civil War, Louisiana stood on the precipice of becoming its own version of a maroon nation. Louisianan freedpeople seized the opportunities provided by emancipation to envision new forms of communal life that rejected the exploitative systems of plantation capitalism and the logic of private property which had attenuated their bondage. Governor Henry C. Warmoth, alarmed by Black peoples’ “radical” aspirations, accused activists like Rodolphe Desdunes of plotting to “establish an African State Government” According to Warmoth, Desdunes encouraged Louisiana’s Black population to “assert themselves and follow Hayti.” These accusations reflected the irrational fears among the planter class which sought to discredit their opponents by linking them to the Black republic. But there was some truth in Warmoth’s accusation: the Afro-Louisianan rural labor movement portended the dismantling of the plantation complex much as Haiti as successfully done.

The ecological transformations across the US South were profound. Freed communities across the South reversed the environmental and social degradation wrought by monoculture, replacing “slave crops” like cotton and sugar with food cultivation and sustainable land use.29 Letters exchanged among Freedmen’s Bureau officials suggest that these communes were widespread, even if official records are scarce. In just three Louisiana parishes—Plaquemines, St. Charles, and Lafourche—there were at least nineteen communes operating in 1865, with some cultivating over 750 acres of land, more than half of which was dedicated to food production. In Lafourche, one Union officer observed that freedpeople had planted corn on former plantations and stored the harvest in warehouses near their cabins. These communes, had they been allowed to flourish, could have fundamentally reshaped the history of the South and the United States.30

Music played a central role in these efforts, laying the groundwork for a new political and aesthetic form during Reconstruction. Brass bands became vital to the cultural and political life of Black communities, turning parades into sites of collective expression and activism. These “brassroots” movements forged a space where new social relations could be enacted, rehearsed, and imagined.

In Alexandria, for instance, a conservative newspaper complained of being awoken “long before daylight” by the “steady tramp of the dark column of the ‘Radical Republican Clubs,’” whose Black activists, “well-dressed, ragged, bare-footed all,” marched to the music of the “promised land.” The New Orleans Tribune, the nation’s first Black daily newspaper, heralded these parades as ushering in a “new and glorious era in our history,” describing scenes of “fifteen thousand Chinese lanterns,” flags flying, and the sound of “drums, fifes, and brass bands” filling the air and human ears in equal measure, affectively creating new commons in sound.31

Brass band performances remapped the sonic and social geographies of Southern cities, projecting Black autonomy and evoking planter-class anxiety. Emily LeConte, a former enslaver, described the sound of brass bands on July 4, 1865, as “too humiliating” to bear, a visceral reminder of the shifting power dynamics. The planter class and their allies responded to these movements with brutal repression. The so-called “Redemption” era sought to dismantle the gains of Reconstruction, exemplified by atrocities like the 1887 Thibodaux Massacre, where the Louisiana Militia and white citizens killed dozens of unarmed Black sugar workers striking for better conditions. Despite this violence, the experimental years of agrarian reform and musical innovation endured, forming part of what Clyde Woods has termed the “scattered, misplaced, and often forgotten movements” of Black workers who envisioned a radical reimagining of regional development in the Delta.

Brass bands became both a contested terrain and a site of resistance. Plantation owners often used these bands as a compensatory measure, providing music in place of the land reform freedpeople demanded. Yet these very bands became conduits for maroon ecologies and communal social relations, fostering an underground barter economy that resisted plantation capitalism. James Humphrey, a music instructor employed by Governor Warmoth, exemplifies this paradox. His grandson later recalled how Humphrey brought home pecans, sweet potatoes, and sugar cane from rural areas, cultivating a garden that supported his family and paid his taxes. These acts of subsistence and exchange reveal a continued maroon ethos—an insistence on sustaining alternative economies even under conditions of oppression.32

Brassroots Democracy, then, was a set of practices as much as a space, both mediated through music and improvisation. Here, new social relations not permissible in the (counter)public sphere could be rehearsed and enacted, where new visions of the commons were created through collective improvisation. And thus, in thinking through these three different topics – the sonic common wind, musical marraonge, and brassroots democracy—it appears that The Haitian Revolution’s songbook wind transcended territorial borders, binding disparate Afro-diasporic communities in a shared, insurgent soundscape that resonated for generations. Music, as both a social practice and a means of territorialization, was an example where the medium was the message: a vessel for translating the radical energies of revolutions macro and micro into a mobile, transnational language. A million daily uprisings became enunciated and reproduced in songs and sounds that traveled from Saint-Domingue to Jamaica, Venezuela, Martinique, Curaçao, Cuba, and New Orleans. These songs did not simply accompany the revolutionary moment—they actively shaped it, embedding narratives of liberation within the aural fabric of everyday life, and terrifying planter classes who could no longer trust the soundscape they had worked so hard to curate. In these echoes, we witness how the Haitian Revolution’s musical reverberations forged a global sensibility of resistance, unsettling the colonial order and laying the groundwork for a new Afro-modern political and artistic consciousness.

- Martin Munro, Different Drummers: Rhythm and Race in the Americas (University of California Press, 2010), 24–77. ↩︎

- Julius Scott, The Common Wind: Afro-American Currents in the Age of the Haitian Revolution (New York: Verso, 2018), 16, 96, 87. ↩︎

- Édouard Glissant, Poetics of Relation (University of Michigan Press, 1997), 63-70. ↩︎

- Julius Scott, The Common Wind: Afro-American Currents in the Age of the Haitian Revolution (New York: Verso, 2018), 16, 96, 87. ↩︎

- Sara E. Johnson, The Fear of French Negroes: Transcolonial Collaboration in the Revolutionary Americas (University of California Press, 2012). ↩︎

- Academia Nacional de la Historia, Caracas, Sección Civiles, Signatura A13–5159–2, report of 24 Feb. 1801; David Geggus, ed., The Haitian Revolution: A Documentary History (Indianapolis: Hackett Publishing

Company, 2014), 188. ↩︎ - Elisabeth Léo, “Les relations entre les Petites Antilles françaises et Haïti, de la politique du refoulement à la résignation, 1804-1825,” Outre-mers, tome 90, n°340-341, 2e semestre 2003. Haïti Première République Noire. pp. 177-206. ↩︎

- Nanette de Jong, Tambú: Curaçao’s African-Caribbean Ritual and the Politics of Memory (Indiana University Press, 2012), 28, 43–44; Alan F. Benjamin, Jews of the Dutch Caribbean: Exploring Ethnic Identity on Curacao (Routledge, 2002), 75–76; Mat Callahan, Songs of Slavery and Emancipation (University Press of Mississippi, 2022), 67. ↩︎

- Édouard Glissant, Poetics of Relation (University of Michigan Press, 1997), 63-70. ↩︎

- Samuel A. Floyd, “Black Music in the Circum-Caribbean,” American Music 17, no. 1 (1999): 1–38. See also Sara E. Johnson, “Cinquillo Consciousness: The Formation of a Pan-Caribbean Musical Aesthetic,” in Music, Writing, and Cultural Unity in the Caribbean, ed. Timothy J. Reiss (Trenton, NJ: Africa World Press, 2004), 35–58. ↩︎

- Matt Sakakeeny, Sue Mobley, and Thomas Jessen Adams, “Introduction: What Lies beyond Histories of Exceptionalism and Cultures of Authenticity,” in Remaking New Orleans: Beyond Exceptionalism and Authenticity, ed. Matt Sakakeeny and Thomas Jessen Adams (Durham: Duke University Press, 2019), 1. ↩︎

- Nathalie Dessens, “St Domingue Refugees in New Orleans: Identity and Cultural Influences,” in Echoes of the Haitian Revolution, 1804-2004, ed. Martin Munro and Elizabeth Walcott-Hackshaw (University of West Indies Press, 2008). ↩︎

- Charlie Guillard placed the ad for this runaway in the Courier de la Louisiane on July 23, 1810. This story is recounted in Rashauna Johnson, Slavery’s Metropolis: Unfree Labor in New Orleans during the Age of Revolutions (Cambridge, Massachusetts: Cambridge University Press, 2016). ↩︎

- Simón Rodríguez, “Reflexiones sobre los defectos que vician la escuela de primeras letras en Caracas y medios de lograr su reforma por un nuevo establecimiento, 19 de mayo de 1794,” in Simón Rodríguez, Escritos, ed. Pedro Grases (Caracas: Imprenta Nacional, 1954), 5–27. ↩︎

- Quincy T. Mills, Cutting Along the Color Line: Black Barbers and Barber Shops in America (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2013), 52-57; “George DeBaptiste,” Detroit Advertiser and Tribune February 23, 1875. Frederick Douglas complains of Black barber-guitarists in “Make Your Sons Mechanics and Farmers,” Frederick Douglass’ Paper, March 18, 1853. See also Leslie M. Harris, In the Shadow of Slavery: African Americans in New York City, 1626-1863 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2004), 240-242. ↩︎

- Cristina Soriano, Tides of Revolution: Information, Insurgencies, and the Crisis of Colonial Rule in Venezuela (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 2018). ↩︎

- Hannah Farnham Sawyer Lee, Memoir of Pierre Toussaint, Born a Slave in St. Domingo, 2nd ed. (1854; reprint, Westport, CT: Negro University Press, 1970); Douglas W. Bristol Jr., Knights of the Razor: Black Barbers in Slavery and Freedom (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2009) ↩︎

- Donald M. Marquis, In Search of Buddy Bolden: First Man of Jazz (Louisiana State University Press, 2005), 41. ↩︎

- The jazz pianist Willie “The Lion” Smith, for instance, indicates that his uncle was a barbershop singer, and his mother was “Spanish, Negro, Mohawk,” suggesting connections to both Spanish America, North American Indigenous ancestry, and barbershop culture. Willie Smith, Music on My Mind: The Memoirs of an American Pianist (Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1964). For Black barbershop culture and four-part harmony, see Gage Averill, Four Parts, No Waiting: A Social History of American Barbershop Quartet (Oxford University Press, 2003); Vic Hobson, Creating Jazz Counterpoint: New Orleans, Barbershop Harmony, and the Blues (Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 2014); Lynn Abbott, “‘Play That Barber Shop Chord’: A Case for the African-American Origin of Barbershop Harmony,” American Music 10, no. 3 (1992): 289–325. ↩︎

- Angel Adams Parham, American Routes: Racial Palimpsests and the Transformation of Race (Oxford University Press, 2017), 65. ↩︎

- Jean-Pierre Le Glaunec, “Slave Migrations and Slave Control in Spanish and Early American New Orleans,” in Empires of the Imagination: Transatlantic Histories of the Louisiana Purchase, ed. Peter J. Kastor et al. (University of Virginia Press, 2009), 219-222. ↩︎

- Thomas Marc Fiehrer, “African Presence in Colonial Louisiana: An Essay on the Continuity of African Culture,” in Louisiana’s Black Heritage, ed. Robert Macdonald et al. (Louisiana State Museum, 1979), 26; Henry Arnold Kmen, “Singing and Dancing in New Orleans (1791-1841)” (Ph.D. Dissertation, Tulane University, 1961),76, 84; Le Glaunec, “Slave Migrations and Slave Control in Spanish and Early American New Orleans,” 219-222. ↩︎

- Richard Tansey, “Out-of-State Free Blacks in Late Antebellum New Orleans,” Louisiana History: The Journal of the Louisiana Historical Association 22, no. 4 (1981): 369-386. ↩︎

- William C. C. Claiborne, Official Letter Books of W. C. C. Claiborne, 1801–1816, edited by Dunbar Rowland (MS: State Department of Archives and History, 1917) 3:357. ↩︎

- Sara E. Johnson, The Fear of French Negroes: Transcolonial Collaboration in the Revolutionary Americas (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 2012), 144-146. ↩︎

- Frederic Ramsey Papers, MSS 559, Box 16C, Historic New Orleans Collection; Vic Hobson, “New Orleans Jazz and the Blues,” Jazz Perspectives 5, no. 1 (2011): 3-27. ↩︎

- Benjamin Barson, Brassroots Democracy: Maroon Ecologies and the Jazz Commons (Wesleyan University Press, 2024), 38–71. ↩︎

- Johnhenry Gonzalez, Maroon Nation: A History of Revolutionary Haiti (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2019). ↩︎

- Eric Foner, Reconstruction: America’s Unfinished Revolution, 1863-1877 (Harper & Row, 1988), 51–118. ↩︎

- C. Peter Ripley, Slaves and Freedmen in Civil War Louisiana (Louisiana State University Press, 1976), 78. ↩︎

- New Orleans Tribune, May 30, 1867. ↩︎

- Benjamin Barson, “‘You Can Blow Your Brains Out and You Ain’t Getting Nowhere’: Jazz, Collectivism, and the Struggle for Ecological Commons in Louisiana’s Sugar Parishes,” in The Routledge Handbook on Ecosocialism, edited by Leigh Brownhill, Salvatore Engel-Di Mauro, Terran Giacomini, Michael Löwy, and Terisa E. Turner (Abingdon: Routledge, 2021): 201–13. ↩︎