Phonography’s defining traits

0March 25, 2014 by Richard Elliott

In his influential book Capturing Sound: How Technology Has Changed Music, Mark Katz identifies seven traits of sound recording technology that are ‘distinctive and defining’: tangibility, portability, (in)visibility, repeatability, temporality, receptivity, and manipulability (Katz, Capturing Sound, pp. 9-47). While the first of these would seem the most obvious to discuss in relation to musical materiality, all seven of Katz’s traits are relevant to such a discussion.

In his influential book Capturing Sound: How Technology Has Changed Music, Mark Katz identifies seven traits of sound recording technology that are ‘distinctive and defining’: tangibility, portability, (in)visibility, repeatability, temporality, receptivity, and manipulability (Katz, Capturing Sound, pp. 9-47). While the first of these would seem the most obvious to discuss in relation to musical materiality, all seven of Katz’s traits are relevant to such a discussion.

Tangibility relates to the way in which, with the onset of recorded sound, music becomes a thing. Recorded sound did not invent music as an object, and it is important to remember previous examples of the attempt to ‘fix’ or ‘keep’ music, such as notation, written description, ballad sheets, sheet music and even the collecting of musical instruments. But the objects associated with recorded sound–from early cylinders through records and on to CDs–could be seen (and felt and heard) to ‘contain’ music with far greater fidelity and far greater proximity to ‘the thing itself’ than earlier, non-sonic objects.

As many people have shown, this thing-ness would have considerable implications for the association between music and commodification (Eisenberg 2008 is particularly good on this subject). Again, recordings did not invent the connection between music and capital but they did fundamentally reconstitute the capitalist machinery of what would come to be known as the culture industry. This refiguring of music’s potential as commodity means that this particular form of tangibility has survived the recent decline in the prevalence of the recorded object; the digitalizing and virtualizing of culture may have brought about a significant change in what we think of as cultural ‘objects’, but the relationship between culture and capital seems to be as firm in the present as at any point during the last century.

Katz’s second trait, portability, refers to a quality that becomes ever more apparent in the evolution of music-as-thing. Walter Benjamin’s famous analysis of mechanical reproduction highlights portability as one of the ways in which the ‘aura’ of the original artwork is lost. It was the artwork’s location in a particular time and space that contributed to its aura. The mechanically-reproduced object, however, has no need of such an aura given that a vital part of its raison d’être is the freedom it allows its users to have it wherever and whenever they wish. Recorded music can be disseminated to diverse audiences who are severed from the time and space of the original musical moment. As Katz says, with reference to the travelling picò sound systems of Cartagena, Colombia, ‘while recorded music is often decoupled from its origins in space and time, this “loss” begets a contextual promiscuity that allows music to accrue new, rich, and unexpected meanings’ (Katz, p. 15).

By visibility and invisibility, Katz is highlighting the fact that, with recorded sound, there is no need for performers and audiences to see each other. This means that a certain element of expressive communication is withdrawn as there can no longer be a reliance on facial expression or bodily gesture, factors which are important to performers and audience members alike. Audiences cannot read the musicians for clues, nor can performers gauge the response of their audiences to what they are playing.

Repeatability is perhaps one of the more obvious facets of recorded sound, yet it can be conceptually complex, as a number of philosophical words that have taken repetition as their subject have shown. In terms of what Katz would call ‘phonographic effects’–the changes wrought upon musical performance and consumption inaugurated by recorded sound–repetition comes to the fore in the ways in which listeners come to expect certain things from the music they hear. Repetition brings familiarity and, while this can be of great value–for example, in the possibility of studying a particular piece of music, by which we generally mean, in the phonographic era, a particular recording–it can also lead to a sense of disturbance, such as that experienced when a live performance of a recording with which we are intimately familiar does not seem to live up to its recorded counterpart. What we witness here is a process whereby a previously understood precedence–the precedence of the performance to the recording–is seemingly reversed. Musicians, of course, are listeners too and, as Katz suggests, their listening practices and phonographic awareness, will inevitably affect their performance.

Until the introduction of the long-playing disc at the end of the 1940s, listeners were not able to hear more than four and a half minutes of continuous recorded sound. One of the most obvious phonograph effects, then, relates to temporality. Any kind of recording, be it writing, painting, photography or phonography, is a reduction of the complexity of the phenomenal world (but also, paradoxically, an addition to what there is in the world). As a time-based phenomenon, recorded sound inevitably placed an emphasis on the reduction of musical time to what could be fitted into the grooves of the record. A number of writers have attended to the changes undergone by specific musical forms due to the three-minute limit of 78 rpm recordings (see, for example, Vieira Nery 2004: 204; Holst 2006: 54; Conte 1995; Nagoski 2007), though it seems safe to conclude that such compromises were necessary for all musical styles and genres. As Katz relates, the three-minute standard came to be associated with the ‘formula’ for successful pop, though it should also be noted that the subsequent ability to record extended works did not discourage such temporal formulas from being maintained in many genres.

Until the introduction of the long-playing disc at the end of the 1940s, listeners were not able to hear more than four and a half minutes of continuous recorded sound. One of the most obvious phonograph effects, then, relates to temporality. Any kind of recording, be it writing, painting, photography or phonography, is a reduction of the complexity of the phenomenal world (but also, paradoxically, an addition to what there is in the world). As a time-based phenomenon, recorded sound inevitably placed an emphasis on the reduction of musical time to what could be fitted into the grooves of the record. A number of writers have attended to the changes undergone by specific musical forms due to the three-minute limit of 78 rpm recordings (see, for example, Vieira Nery 2004: 204; Holst 2006: 54; Conte 1995; Nagoski 2007), though it seems safe to conclude that such compromises were necessary for all musical styles and genres. As Katz relates, the three-minute standard came to be associated with the ‘formula’ for successful pop, though it should also be noted that the subsequent ability to record extended works did not discourage such temporal formulas from being maintained in many genres.

The transcriptive nature of most recording up the 1950s was less to with a desire for authenticity than a necessity. The rather cumbersome process of recording during this early period necessitated a large amount of manipulation, from the placing of singers and musicians at various points in relation to the microphone to the elimination of certain instruments and styles and their replacement with more phonograph-friendly alternatives. However, while these factors could be defined in terms of the manipulation necessary to secure good recordings, Katz chooses to categorise them as examples of ‘receptivity‘ his least well-defined category. ‘Manipulability‘, by contrast, is used to refer to the ability, with the advent of tape recording in the 1940s and digital recording at the end of the 1970s, to manipulate the recorded object itself. This might involve the splicing together of different recordings to create a single recorded ‘text’, such as happened with Teo Macero’s recordings of Mile Davis in the 1960s and George Martin’s of the Beatles in the same decade. Or it might involve the sampling of recordings to use as a background texture or foregrounded, featured element in new recordings, as became the practice in hip-hop and musics influenced by it.

The role of producers, studio engineers and, in the case of hip hop and dance music, deejays became far more prominent die to these kinds of sonic manipulation.Before the ‘turntablism’ of hip hop deejays, playback devices and records had been used as instruments or instrumental textures by a number of artists, including John Cage in his Imaginary Landscape No. 1 (1939). The use and deliberate misuse of recordings and playback technology constitute, for Caleb Kelly, a notable strand of subversive art in the second half of the twentieth century (Kelly 2009). With reference to the criticisms levelled against recording technology by thinkers such as Theodor Adorno and Jacques Attali, Kelly suggests that practitioners of what he calls ‘cracked media’ challenge the intended uses of technology and substitute alternative forms of labour via subversive acts of misuse and abuse.

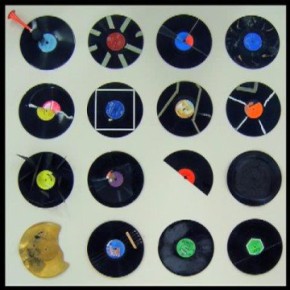

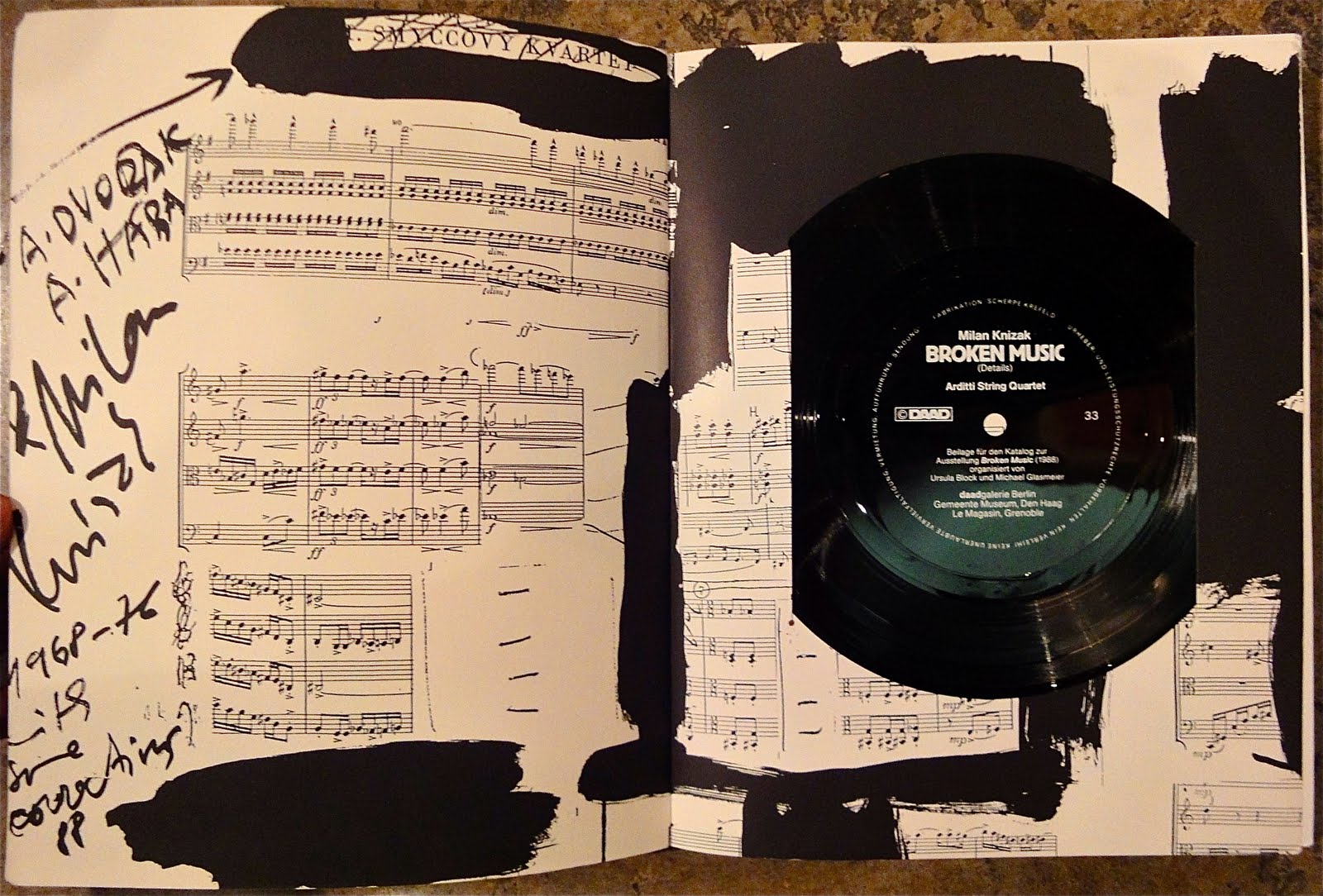

Korean-born Nam June Paik, for example, modified turntables to allow numerous randomly accessed records to be played on them simultaneously, the end results working as both quirky sculptures and manifestations of sound art. Czech artist Milan Knižak put on ritualistic happenings in the streets of Prague before moving to sound-based work that included the physical alteration and mutilation of vinyl records. Works such as Broken Music applied cut-up techniques to records, cracking, dismantling, and rebuilding them so that they played reconfigured music. US-based Christian Marclay also worked with broken and cut-up records on projects which complemented his work in the visual arts while simultaneously performing as a radical turntablist. Japan’s Yasunao Tone performed similar mutilations on compact discs, “wounding” them in order to change and distort their data. The German band Oval, meanwhile, was instrumental in turning the sound of CD malfunction into aesthetically pleasing music, using glitch as a texture in pop songs.

Korean-born Nam June Paik, for example, modified turntables to allow numerous randomly accessed records to be played on them simultaneously, the end results working as both quirky sculptures and manifestations of sound art. Czech artist Milan Knižak put on ritualistic happenings in the streets of Prague before moving to sound-based work that included the physical alteration and mutilation of vinyl records. Works such as Broken Music applied cut-up techniques to records, cracking, dismantling, and rebuilding them so that they played reconfigured music. US-based Christian Marclay also worked with broken and cut-up records on projects which complemented his work in the visual arts while simultaneously performing as a radical turntablist. Japan’s Yasunao Tone performed similar mutilations on compact discs, “wounding” them in order to change and distort their data. The German band Oval, meanwhile, was instrumental in turning the sound of CD malfunction into aesthetically pleasing music, using glitch as a texture in pop songs.

There are numerous aspects that Katz does not attend to in the initial presentation of his seven traits. One is the way in which some of them work together. Temporality and repeatability, for example, should be thought of as necessarily connected. Of particular importance to our project are the ways in which time and repetition shape and are shaped by memory acts, whether voluntary or involuntary. Music performs its evocation work by tapping into the ability to render the past in the present to a seemingly infinite degree. Temporality here refers not only to the length of a recording but to the duration of the remembered experience that the recording summons up. Length of recording is still important, however, because one of the many magical qualities of the recording is its very brevity in comparison to the experience it evokes. Michael Pickering and Emily Keightley attend to this issue when they write, ‘It is obvious that one piece of music did not play throughout our memories of high school or university, yet it may only take one piece of music to evoke sensuously the memories or experiences of those times in our lives.’ (Keightley and Pickering 2006: 153). There is, then, a synechdocal quality to recording, in which the recorded fragment can stand in for and even substitute phenomenal experience. When this aspect is allied to the Proustian concepts of voluntary and involuntary memory, there is a wealth of useful analysis to be carried out.

References

Conte, Pat (1995). ‘The Fourth World: From Stone Age to New Age’, liner notes to The Secret Museum of Mankind. Yazoo 7004.

Eisenberg, Evan (1988). The Recording Angel: Music, Records and Culture from Aristotle to Zappa. London: Picador.

Gronow, Pekka and Ilpo Saunio (1998). An International History of the Recording Industry. Trans. Christopher Moseley. London and New York: Cassell.

Holst, Gail (2006). Road to Rembetika. 4th edn. Evia: Denise Harvey.

Katz, Mark (2004). Capturing Sound: How Technology Has Changed Music. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Keightley, Emily and Pickering, Michael (2006). ‘For the Record: Popular Music and Photography as Technologies of Memory’. European Journal of Cultural Studies, Vol. 9, No. 2: 149-65.

Kelly, Caleb (2009). Cracked Media: The Sound of Malfunction. MIT Press.

Nagoski, Ian(2007). Liner notes to Black Mirror: Reflections in Global Musics (1918-1955). Dust-to-Digital DT-10.

Vieira Nery, Rui (2004). Para uma História do Fado. Lisbon: Corda Seca & Público.

Category Research | Tags: cracked media, phonography, sound recordings

Leave a Reply