WHORES’ WISDOM: Revolución puta (Whore Revolution, María Galindo, 2023)

Today at Mediático we are delighted to present a first post by Isabel Seguí. Dr Seguí is a lecturer in Film Studies at the University of St Andrews. She specialises in women-led collective nonfiction filmmaking in the Andes. In this post, Dr Seguí offers a review of Bolivian activist, artist and thinker María Galindo’s new film Revolución Puta (Whore’s Revolucion 2023) that had its European premiere this past summer in various Spanish cities Zaragoza, Barcelona, Valencia, Madrid y Santander. This post is a translation of a piece that originally appeared in Spanish in El Salto

WHORES’ WISDOM

On the latest film by María Galindo

There are many ways to analyse a documentary film or a docu-fiction. If its subject matter is the life or political action of people with little access to the means of production, one of the most productive ways is to look at who is speaking so that we can detect practices of ventriloquism and extractivism. Often, the cultural and symbolic capital resulting from a non-fiction film are accrued by the director and not redistributed amongst the film’s subjects. Thus, it is our duty as critical viewers to question the old “giving voice to the voiceless” claim. Because putting a social group on screen is not the same as allowing them to speak up.

The Bolivian activist, artist and thinker María Galindo has released her latest film entitled Revolución puta (Whore Revolution, 2023). In the 50-minute documentary, a production of the anarcha-feminist collective Mujeres Creando, organised and self-managed so Bolivian sex workers speak and so does Galindo, although we do not hear her voice. Galindo has been collaborating with sex workers for more than twenty years. In 2007, she published, with Sonia Sánchez, the book Ninguna mujer nace para puta (No woman is born to be a whore), which, to her dismay, has been co-opted and turned into one of the bibles of Latin American sex work abolitionism.[i]

Galindo’s stance on sex work is refreshing. She has not engaged in the bloody feud around sex work that divides the feminist movement. Neither regulationist nor abolitionist, she is diametrically opposed to any victimisation of women who do sex work. She considers the sex worker a “host of social change (…) a central figure (…) the whore has the wand with which to stir sexualities, break myths, dilute structures of all women and that is why she is an essential subject.”[ii] Galindo situates her film and intended audience (of middle class, female audiences) in a position that is not seeking to save the “putas” (“whores”). Instead, she shows how the sex workers are uniquely placed to handle information about their clients that non sex workers cannot. Galindo is not seeking to save “the putas” (the whores) on the contrary, they handle useful information for us, the non-whores, because we are misguided and know little about men. Indeed we only get to know a few men in depth. The “putas,” on the other hand, accumulate “a quantity of knowledge about affectivity, sexuality, the body, the ailments and the male complexes.”[iii] In addition, because they deal with male violence daily, they know how to avoid and combat it. For all of these reasons —their collected intel and specialised knowledge— sex workers are essential allies in counter-patriarchal struggles.

As allies, the collective Mujeres Creando, cofounded by Galindo, has supported a concrete policy embodied in self-managed prostitution practices. They organise without pimps in premises managed by themselves, and what decades ago seemed like a utopian idea is now the law. Thanks to the work of the Organization of Women in a State of Prostitution (OMESPRO) and Mujeres Creando, the Mayor’s Office of La Paz approved a municipal law that regulates the establishments in which sex work is carried out freely and autonomously to safeguard the safety and health of independent sex workers.

Galindo has always been interested in the recording of performance art, both photographically and on video. There are early and beautiful recordings of street happenings in which she and other founders of Mujeres Creando practically risks their lives. Over time, these recordings have turned into cinematographic exercises in themselves, whilst remaining as pieces of performance art. In Revolución Puta, the film language is heterodox, hard to classify, and unacceptable to the arbiters of Westernised and colonised cinephile taste. Galindo uses urban popular art forms and styles that borrow from the aesthetics of local television and lowbrow advertising, such as split screens, multiple fades, wipes and digital transitions with chroma-like visual effects. She also incorporates still image, animated intertitles, and opts for the almost total absence of static cinematography (in Revolución Puta she even uses drone shots). Galindo’s use of this low brow and “bastardized” visual language in Revolución Puta, while effective and attractive to all audiences, prevents the film from accessing the European festival circuit. Revolución Puta’s televisual and advertising aesthetics do not fit within the parameters adopted by festival gatekeepers. The cinephile taste is clearly codified, homogenised and sanitised.

Ironically, Galindo distributes her films in Europe through the contemporary art circuit — which is even more elitist than the festival realm— but to which she has access due to the prestige of her work and the breadth of her contacts. That is the paradox that accompanies the public figure of María Galindo. In Bolivia, she is maligned by the cultural elites, while in Europe, she is celebrated by the very same institutions that self-conscious and colonised Bolivian cultural elites aspire to be a part of.

Although she never utters a word on the soundtrack, in Revolución Puta, Galindo speaks through her directorial choices in staging, scriptwriting, performance direction, costume design, sets and camera movements. She does not speak alone, however. Danitza Luna, muralist and member of Mujeres Creando, collaborates in the setting design; the trans choreographer Devi Beatrix introduces a surprising professionalism and spectacularity and helps the protagonists, who are not professional dancers or actresses, shake off any embarrassment and stiffness. Her regular collaborator Sergio Calero oversees the music, and the anthem of the whores, the film’s leitmotiv, has lyrics written collectively by dozens of women and music by the Argentine band Kumbia Queers. In addition, Galindo joins forces with local artisans to make the props. The acting and much of the film’s wisdom are provided by the sex workers themselves who perform and also co-script write with Galindo. In sum, Galindo assumes the direction of the film but she does not take on sole authorship of a documentary that is a co-created by the whole crew.

The film is divided into four episodes that build towards a crescendo. It starts with a simple question, “what is a job?”,and ends by burning in effigy of the “pimp” state. At the opening, a group of sex workers dance behind the banner of their sisterhood through a street market in El Alto while they ask the vendors about the differences between their jobs. The film favours a reversal of traditional roles. Those who are usually silenced are the ones asking the questions here. The empathy shown by the merchants stands out. Women street vendors, in addition to sex workers, are another group Galindo claims as key to Bolivian society because they are the informal owners of the public space. The film thus enables a side by side examination of the of these two groups of women because as one of the protagonists affirms, female greengrocers, laundresses, doctors and engineers equally have their “pimps.”

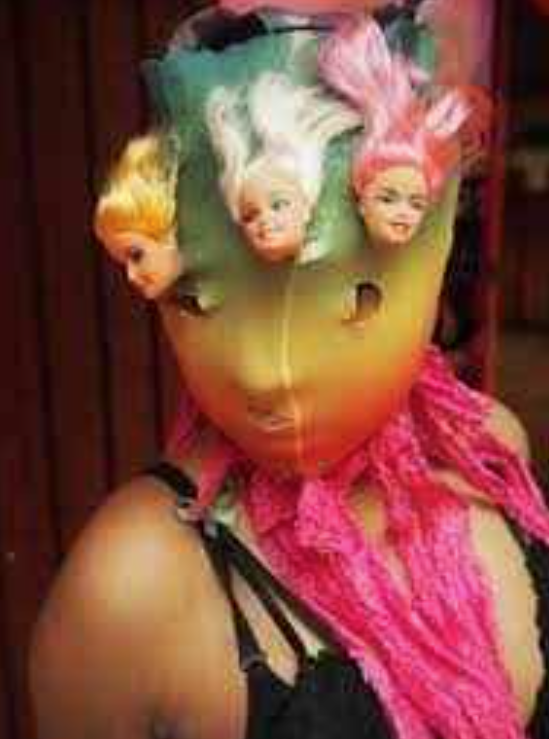

Following this plot line, the second and third episodes, “Lessons for Wives and Girlfriends” and “Testament”, seek to show “the continuity between whore and not whore”[iv] and give value to the knowledge of the trade. In the episode recorded in Santa Cruz de la Sierra, the collective performance is mobilised through the choreography of Oscar Rea, who acts as the masculine archetype —with the words son, policeman, judge, lawyer, pastor, senator, and God written on his naked body. Shots of the masked dancer interacting playfully with the unmasked sex workers are cross cut with testimonies about men’s behaviour in the privacy of brothel rooms. The objective of the section is to offer us information about the roles of teacher, therapist and advisor, which, are also part of sex work.

The next episode is the moving testimony of Cristina Fernández, who, with forty years of experience, decides to retire and, as the matriarch, gathers her colleagues to pass on her wisdom to them as her legacy. This re-enactment, recorded with hand-held camera taken from within the group, is formally very similar to the camera work carried out by Antonio Eguino in The Courage of the People (Jorge Sanjinés, 1971) in a scene in which Domitila Chungara addresses her compañeras of the association of housewives at Siglo XX mine. This doesn’t mean Galindo, or the cameraman, Rafael Venegas, necessarily had that scene from the film as a reference, nor were they trying to compare Cristina and Domitila’s leadership. The similarity is simply the result of the organic way of recording a re-enactment of this type. Still, the parallels between the camera work in both scenes allows us to connect and affirm the “central continuity between those who are ‘putas’ and those who are not” in the cinematic memory and the history of grassroots women’s political culture in Bolivia.

Revolución Puta (María Galindo, 2023)

As a good anarchist, Galindo ends the film demanding the Bolivian State stop being a pimp. At San Francisco square, a place in the city of La Paz that has traditionally served as a street arena for all kinds of shows and protests, Mujeres Creando erect a large panel in front of which two sex workers allegorised as Puta Medusa (Medusa Whore) and Puta Bendición (Blessing Whore) ask the large audience “has anyone ever heard a whore speak?” The vindication of the collective agenda of sex workers in the square is rooted in centuries-old protests carried out in that same space, which is itself charged with symbolism since it is where the indigenous and colonial urban fabrics meet. The specter of the voices of indigenous peasant women, mining housewives, street vendors, and anarchist unions of cooks and florists, who have protested there in the past, materialises in the square accompanying Medusa and Blessing, who end up setting fire to the enormous stage representing State institutions. Ending a movie with a fire is a well-tested cathartic device. The allegories, Medusa and Blessing, epitomise subaltern Bolivian women when they say “the Bolivian State does not see us as thinking people, as part of the people, wants us to be mute.” The public at San Francisco applauds fervently at this poignant statement and at the fire.

The reaction of Western or Westernised audiences to Revolución Puta will be another story. Galindo offers us a window on the topic, but not a “naturalistic” frame. Instead, she offers the spectator a provocative frame that doesn’t allow for the victimisation or re-victimisation of the subjects and prevents spectators from situating themselves as compassionate onlookers. White, middle-class women viewers could not appropriate this story, even if we wanted to. The film’s testimony of the “whores” is not given to us for easy consumption. They will not be used as pawns in the ideological conflicts of bourgeois feminists.

Whore Revolution is a direct appeal, a hand extended to us, those other “whores” who don’t get paid and don’t even realize our own status. The film’s sex workers are generously teaching us a lesson, if were are at all able to grasp it. And if we can’t understand that lesson, we won’t be able to digest it at will. It will give us indigestion. That is the mediation Galindo brings to the voice of a group she does not belong to. That is the materialization of her alliance. At this political moment in which the far right, allied with “organized pimping,” is taking power in the Spanish state, a coalition between all “whores”, whether or not we are sex workers, is crucial. If this is a war, Galindo proposes that we open ourselves to the possibility of incorporating sex workers as strategic partners because they know our opponent most intimately. Shall we listen to them?

[i] María Galindo y Sonia Sánchez. Ninguna mujer nace para puta. La Paz: Mujeres Creando, 2007.

[ii] María Galindo. Feminismo Bastardo. Lima: Isole-Mujeres Creando, 2022: 55

[iii] Ibid 60

[iv] Ibid 59