“I like what you dislike / I like what you fear”*: On Vedettes, Night Life, Beauty, and Aging in Bellas de noche / Beauties of the Night (María José Cuevas, 2016)

Today Mediático is delighted to present an inaugural post from Laura Gutierrez, Associate Professor of Performance and Visual Culture studies at the University of Texas at Austin and author of Performing Mexicanidad: Vendidas y Cabareteras on the Transnational Stage (University of Texas Press, 2010). Gutierrez is currently working on the capaciousness of cabaret culture in two book-length projects, one on cine de rumberas from the 1940s and 1950s and the second on Mexican political cabaret from the second half of the 20th century and beginning of the 21st century. Additionally she is writing essays on contemporary Latina/o performance and visual culture.

*For the title of this brief review, I have taken the liberty of translating two verses from a song made popular by Lyn May, “A mí me gusta” / “What I Like”. In Spanish she and the chorus sing: “A mi me gusta lo que te disgusta / A mi me gusta lo que a ti te asusta”(“I like what you dislike/ I like what you fear”). The archive material used in Bellas de noche of May singing this song comes from her performance as the character Mink in Burlesque (René Cardona, 1980), but it is also a song she recorded and performed live on cabaret stages.

During the Ambulante Documentary Film Festival that kicked off in Mexico City in April of 2016, I was fortunate enough to be at the first public screening of María José Cuevas’ debut documentary Bellas de noche/Beauties of the Night. I had seen snippets of the documentary as well as a version prior to the final cut, but watching the film in collectivity, with three of the vedettes (translated in the documentary’s subtitles as showgirls) featured in the documentary sitting in the row in front of me, and sensing the pleasure all around, scopophilic or otherwise, is one of my most cherished moments of 2016. This shared experience made evident to me that Bellas de noche was destined to become a favorite among audiences and critics if distributed and disseminated adequately. My reason for having thought this can be summarized, but is hardly condensed, with the following: Cuevas treats her subjects with love and respect, but she also highlights both their pain and joy of living with such an intimate care that we as audiences also come to love and care for them. Additionally, Cuevas and her editor, Ximena Cuevas (sister by relation), masterfully weave in a series of narratives about these fierce women who have had to re-invent themselves as their shining stage and screen careers have begun to dim. In short, the documentary features the contemporary living situation of five aging vedettes who triumphed on Mexico’s cabaret variety stages and commercial films in the 1970s and 1980s. And after Ambulante, Bellas de noche was picked up for other festivals, most notably Toronto International Film Festival, Telluride Film Festival, Morelia International Film Festival, Los Cabos International Film Festival, and the International Documentary Film Festival in Amsterdam. Having won awards in several of those occasions, the documentary was released commercially on November 25 in cinemas all over Mexico, where it had a close to three-month run (something that seldom occurs in Mexico for Mexican films) and simultaneously also released internationally via Netflix. And as of February 25 of 2017 Bellas de noche was being streamed through Netflix in Mexico.

As I have suggested, the documentary’s success can be attributed to the fact that Bellas de noche is a true testament to these aging showgirls’ endurance and their desire to live and love (themselves most importantly). But it is an important documentary for other reasons as well: Bellas de noche pushes us to re-think film and stage work, particularly the sort of work that is categorized as bawdy and vulgar (and therefore of lesser value) in the Mexican cultural sphere because of its overt and apparently overly emphasized forms of sex and sexuality. Bellas de noche, in other words, dares us to re-think “taste” and what we previously thought we disliked, and even what we have previously “feared.” While these women have enjoyed an iconic status, particularly thirty years ago when they were most in evidence on stage and screen, this work has for the most part been dismissed by many film scholars and critics. However, with the recent boom in documentary production in Mexico, Bellas de noche belongs to a cluster of documentaries that help us re-conceptualize Mexican cabaret culture, specifically as it relates to aging, sex and sexuality.

One of these documentaries, Maya Goded’s Plaza de la Soledad, was also released in early 2016 and has been participating in the festival circuit, at times alongside Bellas de noche. Goded’s first full-length feature also treats aging women, but in this particular case it is sex workers who continue to labor with their bodies in some of the most impoverished areas of Mexico City’s historical center. Connected to Bellas de noche through the themes of aging, sex, and sexuality, a desire to love and be loved, and basic survival strategies, both documentaries make use of a similar repertoire of songs that depict women laboring in cabarets, most specifically those popularized by the La Sonora Santanera. For example, one of the opening scenes of Goded’s Plaza de la Soledad (also featured in the trailer) frames the sex workers featured in the documentary riding along in a van. When La Sonora Santanera’s “Amor de cabaret” begins to play, all of the women begin singing in unison. Another of these clustered documentaries, and a significant precursor to Bellas de noche is another film that reconsiders female sexuality and laboring bodies alongside Mexican film history.

Plaza de Soledad (Maya Goded, 2016)

Viviana García Besné’s Perdida (2010) was shown in festivals, but never released commercially. The documentary Perdida, which can be translated as “Lost Woman” is similar to Bellas de note in that it also owes its title to a fiction feature film from a previous period, Fernando A. Rivero’s Perdida (1950) featuring the famous Cuban-born rumbera Ninón Sevilla. [1] Perdida is important for several reasons, but amongst them is the ways in which it leaves us with no choice but to reconsider Mexican cinema and the way its been treated by film critics and scholars. It does so by assembling rich archival material from commercial films that have been almost completely left out of Mexican film history because they belong to what are considered lesser genres, as well as original material, as it tells the story of the Calderón family film production companies.[2] In addition to the reconsideration of the place of rumberas in Mexican cinema, Perdida is important for Bellas de noche because it includes in its reassessment those film genres dubbed ficheras or sexy comedias that were perceived to be an embarrassment to Mexican film culture and are said to be the reason for the demise of Mexican cinema starting in the 1970s.[3] And here is the direct link between Cuevas’ documentary and García Besné’s, some of the vedettes featured in Bellas de noche starred in these films from the decades of the 1970s and 1980s, but Perdida is the first documentary to treat these films produced by the Calderón family with a more equalizing gesture by placing them into a defined historical, personal, political and economical context.

One of the primary reasons to value Cuevas’ Bellas de noche therefore is because it is a most refreshing way for all to see how Mexicans view themselves, in some refracted fashion, in relationship to sex and sexuality.[4] But it is also an invitation for us to rethink Mexican film history and popular culture and to consider cabaret culture and the films that reflect that culture as constitutive of the Mexican public cultural sphere, not as forgotten or forsaken cultural narratives but with significant stories still left to tell.

Vedetismo and Beyond

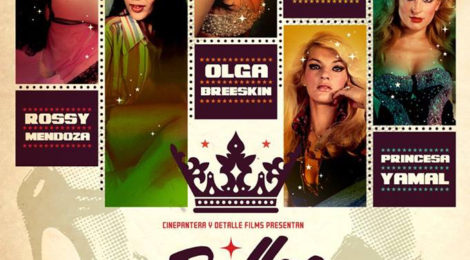

As the opening credits (white letters on black backdrop) of Bellas de noche begin to roll, the spectators hear a strip tease melody. Less than a minute later, we are treated to a brief burlesque number featuring the infamous showgirl Lyn May as seen originally in Alberto Issac’s Tivoli (1974). This sequence is followed by a series of snippets of interviews recorded during the same period of people, mostly women, who are asked their thoughts on the concept of the vedette. The term vedette, although not one used in the English language with regularity, perfectly encapsulates a broad spectrum of meanings and artistic practices: dancing, singing, and acting. In sum, she is a risqué cabaret performer who uses her overtly sexualized body to bring pleasure to her audiences. Lyn May is one of the vedettes featured in this first feature-length documentary by Cuevas, the others are Olga Breeskin, Rossy Mendoza, Princesa Yamal, and Wanda Seux. However, Bellas de noche is more than an homage to the stage and film work of these showgirls and their notions of beauty and use of sex/sexuality to allure audiences, though it is those things too. I believe that the most amazing feat of this documentary is the way in which Cuevas—whose love for her subjects is evident and should be applauded, as well as for her tenacity as she worked tirelessly for ten years to complete this film—is able to go beyond the actual nudity of these cabaret performers to present them to us in all their nakedness.

Bellas de Noche (Maria José Cuevas, 2016): Rossy Mendoza

This shift from this sense of nudity to nakedness that I am suggesting occurs explicitly at about twenty-six minutes into the documentary. Cuevas, working closely with her editor Ximena Cuevas, an amazing filmmaker and video artists in her own right, uses a scene with Rossy Mendoza to enact a narrative break in Bellas de noche. As part of a series of sequences that feature her birthday celebration, Rossy Mendoza is seen first hitting a Betty Boop piñata. Prior to this moment there has been ample discussion on the concept of vedetismo and what is required—beauty, self-assurance, and nudity—for success. This discussion is done either via direct interviews, as with Rossy Mendoza or via a number by Lyn May doing her famous song “A mí me gusta,” but most directly via a series of still shots featuring the vedettes May, Mendoza, Breeskin, Yamal, and Seux in nude pin-ups. After these still shots, we see Rossy Mendoza hit the piñata. And when it finally breaks open, we as audience members begin to see to what’s inside each of these risqué cabaret artists, where they are now, how they have handled decaying beauty and aging, poverty, illnesses, and shifts in career focus, among other things. Bellas de noche shows us how they have been able to survive and how they have had to re-invent themselves in a judgmental and ageist society that continues to have rigid standards of beauty and discards those bodies that it once consumed for pleasure purposes but which it no longer finds attractive.

Bellas de Noche (Maria José Cuevas, 2016): Wanda Seux

It is from this moment onward that we begin to delve into the life of these women and come close to loving them as much as Cuevas does. Although archival material is still used, as well as important musical sources, specifically songs by La Sonora Santanera such as “Luces de Nueva York” and “La Boa,” Bellas de noche mostly uses newly recorded material in the form of intimate interviews with the sixty-plus year old vedettes or primary sourced visual material that documents the everyday life of these women, their fantasies, their struggles, their philosophy of life and love, amongst other things. The catalyst for Bellas de noche, as Guillermo Sánchez Cervantes stated in his review of the documentary for Gatopardo, was an encounter ten years ago between María José Cuevas and Princesa Yamal, one of the vedettes who in previous years had been embroiled in a scandal that landed her in jail because she allegedly took part in the theft in the National Anthropology Museum in the 1980s. That initial meeting was for another project that never took off. However Cuevas, who had grown up in an environment where high art and so-called frivolous art often inter-mingled because of her family’s proximity to Mexican cabaret culture, decided to make Bellas de noche and extend it to other women beyond Princesa Yamal.

A long term labor of love, which meant not only continuing to build a relationship with the women who are the primary subjects of the documentary, but also researching and digging through archival material as well as seeking financing and constituting a team that would work toward a similar vision, Bellas de noche met its audiences in 2016. The rich archival material that Cuevas amassed in her research is being put to use in important and valuable ways to bring to the fore the work of these vedettes in the 1970s and 1980s, but also to help us to continue to reassess cabaret as part of the Mexican cultural sphere. The most significant of these is the exhibition Las Fabulosas (“The Fabulous Women”) at the Foto Museo Cuatro Caminos in Mexico City that recently closed. The exhibition revolves around the same five figures in Bellas de noche, but also includes two more: Sasha Montenegro and Princesa Leal. In similar ways to the documentary, the main aim of the exhibit is to rethink what has been left out of official visual culture in Mexico primarily due to the subjects represented in the material, deemed to be too bawdy, too risqué, for entertainment only, or any other reason. Here the history of Mexican photography and the works of photographers such as Antonio Caballero, Jesús Magma, and Juan Ponce, are reconsidered and serve to expand our understandings of what images circulate and are part of the Mexican collective imaginary. Additionally, the ways in which social media platforms also facilitate the connection between the fans of Bellas de noche and these vedette figures is important to consider here, particular in regard to the ways in which the lives of these women are extended beyond the work performed by the documentary. Noteworthy in this regard is the “Bellas de noche” Instagram account, a carefully curated sampling of images of these vedettes that is sure to amplify the visuals and feelings regarding the vedettes and Mexican cabaret culture. The documentary Bellas de noche, the archival material that is used to construct it, and the paratextual materials that exist alongside it are also on occasion activated via events where some of these vedettes appear and/or perform live. Thus we can say that the documentary Bellas de noche is now an integral part of the ways in which the vedettes continue to re-invent themselves, it is almost as if these live performances infuse them with new life. And equally important how the documentary has helped to create a more capacious meaning of what cabaret culture is as well as the role that these vedettes as the main participants have in the Mexican cultural sphere.

[1] In my current research work I am tracing the lineage of these two different moments in Mexican film history and performances of hypersexuality, the 1950s to the 1970s and 80s.

[2] See Andrew Syder and Dolores Tierney (2005) “Mexploitation/Exploitation: Or How a Crime-Fighting Vampire-Slayer Almost Found Himself in a Sword-and-Sandals Epic” in Stephen J. Schneider and Tony Williams (eds) Horror International Detroit: Wayne State University Press and Tierney (2014) “Mapping Cult Cinema in Latin American Film Cultures” Cinema Journal 54.1, 129-135.

[3] García Besné is the grand niece of the three brothers who together formed the Calderón family of producers, the first to have ventured into some of the most commercial film genres in Mexico: cine de rumberas, cine de luchadores, and cine de ficheras, including the so-called first film of this genre Bellas de noche (Miguel Delgado, 1975), which lends its name to Cuevas’ documentary. Additionally, as the inheritor of sorts of that archive, García Besné was generous with Cuevas with material.

[4] Other possible documentaries to include here are: Casa Roshell (2017) by Camila José Donoso, Made in Bangkok (2015) by Flavio Florencio, and Quebranto (2013) by Roberto Fiesco, all of which feature transgender characters who have performed at one point or another in cabarets in Mexico.