Peru as a New Site of Authenticity in COOKED and CHELSEA DOES by Niamh Thornton

Today, Mediático presents a short essay by Niamh Thornton, Reader in Latin American studies at the University of Liverpool and a contributing editor of Mediático. Her recent publications include Revolution and Rebellion in Mexican Cinema (New York: Bloomsbury, 2013) and, with Catherine Leen, an edited collection of essays International Perspectives on Chicana/o Studies: This World is My Place (New York and London: Routledge, 2013). She has published a number of peer-reviewed chapters and articles on the war story in film and literature, digital cultures and star studies. For more, see her website: niamhthornton.net or follow her on Twitter @enortee.

By Niamh Thornton

Two recent Netflix documentaries feature Latin America, specifically Peru: Cooked (Various, 2016) and Chelsea Does (Edie Schmidt, 2016-). Both present Peru as an ancient land and source for authentic knowledge and experiences. What may seem to be a benign expression of respect for millenarian traditions in Cooked, is a repetition of the othering that reinforces old colonial prejudices. Whilst Chelsea Does can be read to contain within it the means of challenging the very same prejudices that on face value it repeats.

Over the four episodes in the first series of Chelsea Does the US comedian, Chelsea Handler, tries out different experiences under a uniting title: Marriage, Silicon Valley, Racism, and Drugs. It is part reality show where we get an insight into Handler’s world. Significant segments of some of the episodes are shot in her Los Angeles home and her staff and friends (these may be ‘friends’) feature throughout, some of whom are celebrities and actors. She presents herself as an abrasive, somewhat chaotic, party girl, who is on a quest to discover more about herself and the country she lives in. There is much to recommend the ‘Racism’ episode where she reveals the racism inherent in living in Los Angeles, as well as elsewhere in the US, through her persistent and direct style of questioning and the resulting mix of awkward pauses and open declarations by her interviewees. In her discussion of the series The Atlantic writer Sophie Gilbert sets up a false dichotomy between documentary and reality TV, however, she gets it right when she states that “The show veers between being frustratingly shallow and oddly intense, never quite finding the ground it needs to regulate its tone” and episode four ‘Chelsea Does Drugs’ is a good example of this. But, the series also challenges us to questions its own truths.

In ‘Chelsea Does Drugs’ Handler goes to Peru to take ayahuasca. Little known outside of Peru before it received celebrity endorsement, the ayahuasca ceremony has been covered by publications as diverse as Elle and National Geographic. Claims are made as to its physical and spiritual healing powers, and a tourist industry has developed to accommodate travellers keen to seek out this experience.

In the episode Handler takes ayahuasca twice, once in the company of two of her friends, a Shaman, and a translator, and the second time in the company of the Shaman. She claims that the first time it had no effect and the second it brought her to some level of self-awareness. Much could be made of the way money is used to co-opt another’s sacred space and the power structures that are involved in this exchange between Handler and her friends and the shaman, but that will have to take place elsewhere. What I am interested in is how we can both be complicit in and read against the ayahuasca experience that this episode tells. The level of irony and emotional distancing employed by Handler throughout the series encourages the viewer to not take what is said at face value. As in the earlier episode about racism, the pauses and gaps of her interlocutors in the US south when asked to describe their awareness of racism in their locale, speaks volumes about its lived presence. So too, can the untold be a means of challenging the authenticity of experience in the ceremony we watch taking place in episode four. Added to this is the impossibility of knowing what is going on in Handler’s head during either of the ceremonies, the experience is significantly more prosaic and less life altering than that presented in either Elle or The National Geographic. Thus, the traveller’s authentic Peru and the transformative ayahuasca are implicitly critiqued in this telling.

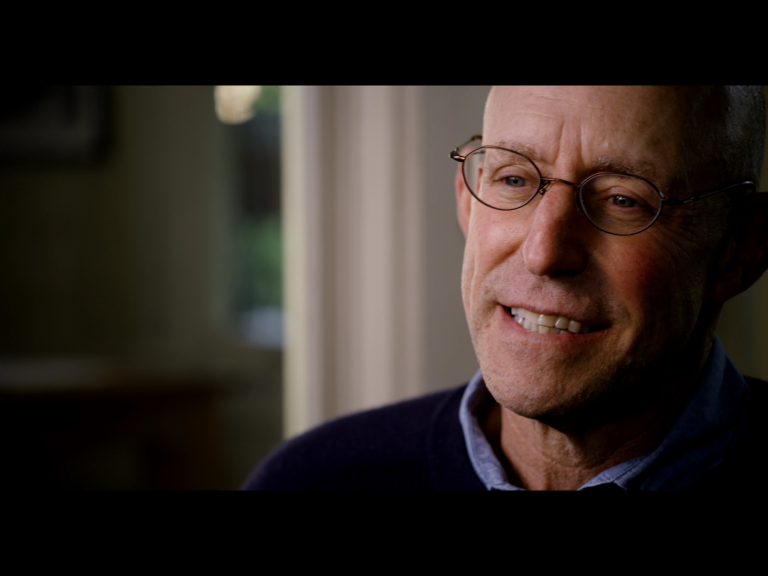

Far more problematic, and more conventionally told is Cooked. Based on Michael Pollan’s 2013 eponymous book it is in four parts: ‘Fire’ (Alex Gibney), ‘Water’ (Caroline Suh), ‘Air’ (Ryan Miller), and ‘Earth’ (Peter Bull). The focus of each is respectively: cooking over flames, cooking in water, bread making, and fermentation. Pollan editorialises whilst the camera travels the world intercut with segments in his home as we observe him undertaking a project related to the topic of the episode. For example, in ‘Fire’ a friend helps him to cook a whole pig in his back yard and in ‘Earth’ he brews beer with his son and another friend. The key messages of the series are that ‘we’ should cook more, source our food locally, and return to artisanal makers thus avoiding processed food. However, one of the failings is well summed up by The New York Times review of the series:

Mr. Pollan’s messages are important to hear and are engagingly presented in this series. Still, there’s a disconnect that’s never addressed. It would be great if all 7.4 billion of us could hunt our own lizards and cook them over an open fire, spend hours baking our own bread from grain milled on stone, and so on. But there’s a gentrification to Mr. Pollan’s brand of culinary advocacy.

The world’s poorest people — some seen in idyllic imagery here — have to devote long hours to basic subsistence, and the world’s relatively well off have the luxury to indulge in artisanal cooking. Yet applying his ideas across the whole range of human circumstances is a trickier subject than this pretty series wants to tackle.

Furthermore, the reviewer criticises him for ‘food-shaming’ and piling on guilt for ‘us’ not cooking more. I would add to that fat shaming, a privileging of (mostly) White male labour, and a troubling exoticisation of other cultures. This is done visually and through Pollan’s narration. The series often intercuts between Pollan and US-based artisan farmers, cooks, brewers, and bakers, and those from other cultures, as if to create an equivalency and equality between these, the result is that it trivialises the non-US producers. Although the reality is more complex, the editing means that the practice of these US makers and producers becomes a facile re-appropriation ignoring that access to their produce and skills is available either to those few with the time and money to indulge in them or others in the majority world forced into continuing time- and labour-consuming practices to produce food. Underlying all this is the message that ‘we’ should change our ways.

It is this ‘we’ that is repeated throughout that is the most troubling recurrent strand in the series. Peru appears in chapter four, ‘Earth’ as a place of chocolate production. The process of fermentation in chocolate is the reason for its inclusion. Pollan’s voiceover flattens out differences between the indigenous peoples of Latin America and ignores the historical consensus that chocolate originated in Mesoamerica. But, Latin Americans are but one of the ‘they’ against which this ‘we’ is to be measured. All cultures become sources of inspiration for food, places of origin for authentic means of production, ancient traditions to be borrowed from so that the unifying ‘we’ can become healthier, more fulfilled, and guilt free.

In Pollan’s documentary with its ostensible sourcing of foods and occasional nod to some troubling aspects of history is superficially a celebration of other cultures (not least in the beautiful cinematography employed), but it is merely an exoticisation of differences without reaching any proper understanding of the complexities involved. In contrast, Handler’s crass, sometimes boorish, celebrity persona allows for spaces to critique her behaviour and the ways in which she and others like her are appropriating other cultures for personal enlightenment.