A Screening Programme at the Frankfurt Filmmuseum, November 23-24, 2013

Curated by Cristina Álvarez López and Adrian Martin

Session 1 (70 mins, with introduction) Saturday 23 November 6-7.30pm

1) Rose Hobart – Joseph Cornell, 1936 (19 min)

Rose Hobart consists almost entirely of footage taken from East of Borneo, a 1931 jungle B-film starring the nearly forgotten actress, Rose Hobart. Cornell condensed the 77-minute feature into a 19 minute short, removing virtually every shot that didn’t feature Hobart, as well as all of the action sequences. In so doing, he utterly transforms the images, stripping away the awkward construction and stilted drama of the original to reveal the wonderful sense of mystery that saturates the greatest early genre films. (Brian L. Frye, Senses of Cinema, 2001)

2) Alone. Life Wastes Andy Hardy – Martin Arnold, 1998 (15 min)

Alone comprises, along with Pièce touchée (1989) and Passage à l’acte (1993), a “trilogy of compulsive repetition”. Arnold’s signature style applies the technique of forward-and-back looping – images repeated in a two steps forward, one step back pattern – to banal interstitial sequences from classical Hollywood films, propelling the characters through a scene in stuttering slow motion. Frozen and replayed, they seem to capture moments of unconscious desire and repression unwittingly trapped between the 24-frames-per-second which ground cinematic movement. (Michael Zyrd)

Alone comprises, along with Pièce touchée (1989) and Passage à l’acte (1993), a “trilogy of compulsive repetition”. Arnold’s signature style applies the technique of forward-and-back looping – images repeated in a two steps forward, one step back pattern – to banal interstitial sequences from classical Hollywood films, propelling the characters through a scene in stuttering slow motion. Frozen and replayed, they seem to capture moments of unconscious desire and repression unwittingly trapped between the 24-frames-per-second which ground cinematic movement. (Michael Zyrd)

3) Gravity – Nicolas Provost, 2007 (6 min)

[Gravity Excerpt from Tim Van Laere Gallery]

The cinematic kiss is probably one of the most archetypical images to be found in film history. Playing with the physiological and cinematographic principle of the after-image, Provost causes dozens of kissing scenes from European and American film classics to collide. The reassuring world of multiplied kisses is shattered by a stroboscopic effect that plunges and looses us into the dizzying vertigo of the embrace where love becomes a passionate battle in which monsters are finally unmasked. <www.nicolasprovost.com/films/445/>

4) Variation on the Sunbeam – Aitor Gametxo, 2011 (10 min)

Aitor Gametxo, a 22 year-old film studies graduate in Barcelona, took the entirety of D.W. Griffith’s seminal short film The Sunbeam (1912) and rearranged the footage according to the physical location of each shot, all taking place in a single house. The results reveal that Griffith shot the entire short using five camera setups, which Gametxo arranges according to their proximity to each other within the house; he includes a sixth space for the intertitles. Behold, a movie viewed simultaneously in six dimensions of space, all unfolding in real time. (Kevin B. Lee, Fandor) [For further information see the links here: https://vimeo.com/22696362]

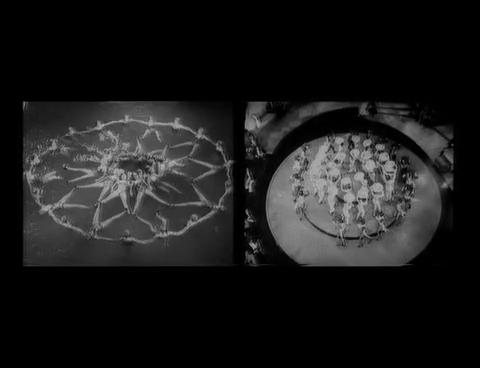

5) Club Video – Philip Brophy, 1985 (20 min)

Club Video began life in 1985 as a video installation arranged across two free-standing monitors and an autonomous stereophonic or quadraphonic sound playback; in recent years it has been reassembled into a split-screen DVD for theatrical screening. Brophy, pillaging VHS tapes (many taped off Australian TV), distills several canonical Hollywood films (including Stagecoach, Touch of Evil and Psycho) into their generic and cinematic essence: gestures, movements, types. Between ‘nightclub video wallpaper’ and close textual analysis, Club Video is prescient of many contemporary trends in the audiovisual essay. (Adrian Martin)

Session 2 (90 min) Sunday 24 November 5-6.30pm

1) Inflames – Covadonga G. Lahera, 2009 (3 mins)

The burning robot of Electroma (2006) traverses the night and the frame in total silence – here, no audio track – until meeting the ‘flames’ of the famous final shot of Two-Lane Blacktop (1971). This is pure creation – not too far from some forms of video art – born from cinema itself, and the reflection on how two images, two films, can talk to each other. It seems to me a very fruitful idea to ‘rub’ these two scenes together – a clear demonstration of what this new criticism that has emerged on-line can offer. What better way of diving into cinema history, and searching for relations or establishing links between two road movies, than to gauge how a ‘hot’ sequence can ignite something adjacent into flames? What better way to prove the debt and filiation of Daft Punk (directors of the fascinating, alien object Electroma) to Monte Hellman, director of that genre masterpiece Two-Lane Blacktop? (José Manuel López, Transit)

2) Pass the Salt – Christian Keathley, 2011 (8 mins)

The form adopted by this audiovisual essay arises from a mix between a detective investigation – which allows us to glimpse the cinephilic obsession of this piece’s author – and legal exposition, a strategy perfectly in accord with the film under analysis. In the first instance, Keathley opts for an analytic process of decomposition to isolate the distinct elements that make up a scene from Otto Preminger’s Anatomy of a Murder (1959). Then, he arranges all the pieces of the puzzle that, ultimately, we see transformed into the premises of a persuasive argument – evidence that proves the interpretation of the selected fragment. (Cristina Álvarez)

3) Beyond Fiction – Johanna Vaude, 2011 (6 mins)

Beyond Fiction was commissioned for the progressive French ‘webzine’ Blow Up, screened on Arte. It is a tribute to John Carpenter’s fantasy/horror films, which touch a disquieting political and ethical realm ‘beyond fiction’. Vaude edits and digitally reworks fragments from many Carpenter movies, changing colour and tone, using superimposition. Her work is ‘figural theory’ in experimental action. (Adrian Martin) [See Johanna Vaude’s website for further information about this film: http://www.johanna-vaude.com/beyond-fiction/]

4) Kristall – Matthias Müller & Christoph Girardet, 2006 (15 mins)

KRISTALL (Excerpt) By Christoph Girardet & Matthias Müller

35 mm Film / HD loop, 1,85:1 | color | sound | 15’, 2006

Kristall (Mirror) creates a melodrama inside seemingly claustrophobic mirrored cabinets. Like an anonymous viewer, the mirror observes scenes of intimacy. It creates an image within an image, providing a frame for the characters. At the same time it makes them appear disjointed and fragmented. This instrument for self-assurance and narcissistic presentation becomes a powerful opponent that increases the sense of fragility, doubt and loss twofold. (Matthias Müller & Christoph Girardet)

5) The Dielman Variations – Fernando Franco, 2010 (12 mins)

The Dielman Variations plays with some fragments of Chantal Akerman’s classic Jeanne Dielman, 23 Quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles (1975), by returning us to the same empty spaces, the slow passage of time, the monotony – all magnified. The stillness and frontality of the Belgian director’s film are underlined by various aesthetic procedures used by Franco, such as superimpositions and fast motion. (Santiago Rubín de Celís, Blogs & Docs) [Further information at Fernando Franco’s website: http://www.fernandofranco.com/fernando-franco-les-variations-dielman_eng.html]

6) What is Neorealism? – Kogonada, 2013 (5 mins)

Every cut is a form of judgment. A cut reveals what matters and what doesn’t. It delineates the essential from the non-essential. To examine the cuts of a filmmaker is to uncover an approach to cinema. The happenstance of Vittorio De Sica’s Terminal Station (1953) and David O. Selznick’s Indiscretion of an American Wife (1953) offers a rare opportunity to compare two cuts of the same film from a leading figure of neorealism and a leading figure of Hollywood. If neorealism exists, it is in contrast to the dominant approach to moviemaking, shaped and exemplified by Hollywood. In comparing these two films, we must ask: what difference does a cut make? (Kogonada, Sight and Sound)

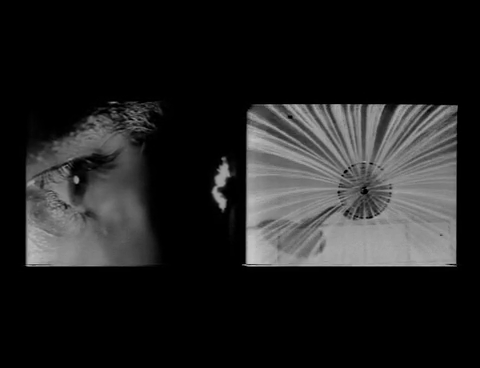

7) True Likeness: On Peeping Tom and Code Unknown – Catherine Grant, 2010 (5 mins)

Following through on the idea of scholar Brigitte Peucker’s ‘gloss’ (a kind of ‘invisible note in the margin’ of Michael Haneke’s films), it struck me that Michael Powell’s Peeping Tom (1960) could be deployed audiovisually, as a kind of cypher-machine through which one might perform a cryptanalysis of the enigmatic and incompletely told Code Unknown (2000). Given that Peeping Tom‘s screenplay was itself written by wartime cryptographer Leo Marks, this would, of course, be a classic Hanekian funny game. (Catherine Grant, Filmanalytical blog)

8) Mogambo – Tag Gallagher, 2010 (13 mins)

Long admired for his books on great directors (John Ford, Roberto Rossellini) and articles adorned with screenshots, the American Tag Gallagher has avowed that he feels he is only now “truly doing criticism” by using and commenting on clips in video-essay form. His analysis of scenes and moments from Ford’s Mogambo (1953) delves deeply into aspects of space, environment, gesture, and character psychology: the best kind of ‘illustrated lecture’. (Cristina Álvarez)

9) Ozu // Passageways – Kogonada, 2012 (2 mins)

A currently popular form of digital editing is the supercut, gathering at fast-speed numerous instances of a particular line of dialogue or situation from many films. Forsaking the usual Hollywood mainstream examples for this type of practice, Kogonada surveys a crucial framing strategy in the work of Japanese master Yasujiro Ozu: the diverse human activities (walking, running, passing through) that occur within corridors, archways, rectangles of all kinds … what film studies identifies as Ozu’s parametric narration, this work displays in dazzling action. (Adrian Martin)

10) Screen and Surface, Soft and Hard: Leos Carax – Cristina Álvarez López and Adrian Martin, 2013 (20 mins)

This sequence of three digital montages can be viewed autonomously, or as part of a larger analytical work on “The Cinema of Leos Carax” in Transit, which also uses screenshots and text. Deploying a split screen arrangement, the montages arrange various motifs, keys and obsessions within Carax’s œuvre: lights, screens, water, holes, surfaces, doors, corridors … plus the sounds of Bowie, Arvo Pärt, a bank of photocopiers and a pinball machine. (Cristina Álvarez & Adrian Martin) [For further information please see: http://cinentransit.com/el-cine-de-leos-carax/#dos]

The embedded videos above appear here with the kind permission of their authors. Warm thanks go to them and to Cristina Álvarez López and Adrian Martin, co-curators of the screening program, for their help with this process.

Sourcing and embedding of online video versions and collection of permissions by Catherine Grant and Chiara Grizzaffi.