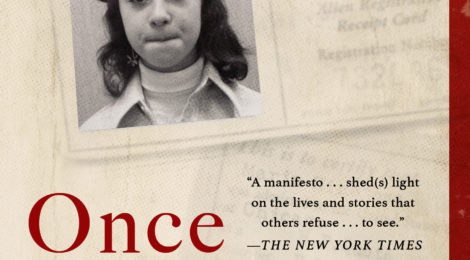

Against Amnesia – Review of Once I Was You: A Memoir of Love and Hate in a Torn America, by María Hinojosa (New York: Atria Books, 2020).

Today Mediático is delighted to present a review of Emmy-award winning journalist María Hinojosa‘s recent memoir Once I Was You (2020) from one of its distinguished contributing editors, Professor Catherine L. Benamou who teaches Film and Media Studies, Visual Studies, and Chicano-Latino Studies at the University of California-Irvine and is the author of It’s All True: Orson Welles’s Pan-American Odyssey (University of California Press, 2007). She is currently working on a book manuscript about transnational television and its diasporic Latinx audiences.

Against Amnesia – Review of Once I Was You: A Memoir of Love and Hate in a Torn America, by María Hinojosa (New York: Atria Books, 2020).

Catherine L. Benamou, University of California-Irvine

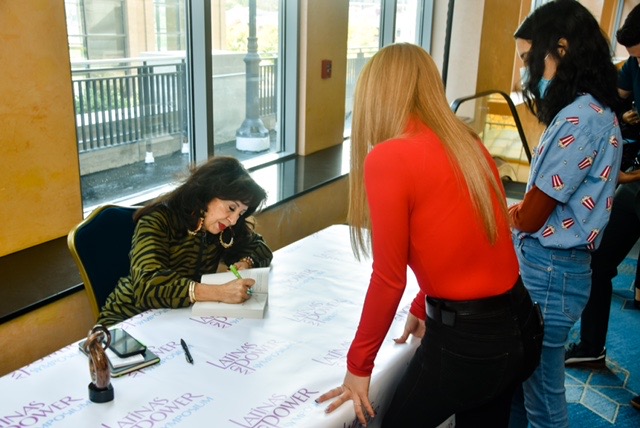

*The author wishes to thank Maria Hinojosa for the images accompanying this article

Of all of the phenomena we encounter in our daily lives, immigration history and media coverage of events are among those that we are most likely to forget, with a few notable exceptions at times of collective trauma. Emmy-award winning journalist María Hinojosa’s recent memoir, Once I Was You (2020) provides a strong antidote to any forgetting by intertwining her own experiences as the daughter of Mexican immigrants with a chronicle of her extensive and accomplished career in broadcast journalism. These two strands intersect at many points, as Hinojosa, distinguished among Latinxs working in Anglophone U.S. media, makes it her job to consistently report on immigration policy and enforcement –and their fallout for millions of unauthorized immigrants and refugees — as a free-lancer for NPR radio, staff reporter for CNN, producer-reporter at PBS, and producer of a podcast, Latino U.S.A., culminating in the hard-hitting Frontline show she produced for PBS, “Lost In Detention,” along with independently produced “In The Thick” podcasts on the subject. Whether reporting on families of victims of the 9/11 attacks on New York’s twin towers for CNN or on the rebuilding of Gulfport, Mississippi and New Orleans on the heels of Hurricane Katrina for PBS Now, Hinojosa has made it a point to bring the stories of the most vulnerable – undocumented workers, women and children – into relief. For the Frontline program, she took television crews for the first time into detention facilities, both profit-hungry and abysmal (in Texas) and “model,” yet prison-like (in Irvine, California and Miami, Florida) to expose the harsh treatment of detainees as the result of “cost-saving” measures and the lack of oversight of prison guards who engaged in what should have been treated as criminal behavior – sexual harassment and assault, serving contaminated food, deprivation of mental health services, and cruel solitary confinement. One story in particular stands out – a “ride along” with ICE (Immigration Control and Enforcement) officers disguised as police to the homes of middle-aged Latinxs in East Los Angeles who had been arrested on DUIs decades prior, only to see them abruptly removed in handcuffs at dawn.

The power of these mediations is augmented as Hinojosa provides rare glimpses into the behind-the-scenes decision making and newsroom politics surrounding the production of her major news reports and documentaries. We get to follow stories from their conception through the approval process into production. Hinojosa thus puts a human face to what usually remains abstract and hidden from view, what tends to be compressed in our imaginaries into organizational monoliths. She stresses the importance of collegiality and collaboration among those sharing a commitment to giving a powerful voice to those who have been silenced by the dominant “anti-terrorism” discourse and institutionalized racism. She stands by her Latinx colleagues when they lobby senior CNN executives insisting in response to Lou Dobbs’ anti-immigrant tirades that a contrapuntal version presenting an immigrant perspective be allowed to air.

The memoir begins with an exchange of glances with a child refugee on her way to a Texas detention center, juxtaposed with Hinojosa’s near separation from her own mother and siblings when an immigration official tried (unsuccessfully) to quarantine her upon their arrival in Texas in 1962, and it ends long after Hinojosa herself becomes a U.S. citizen as a young adult, to focus on her encounter in New York City with a young Central American single mother and disabled child, both recently released from detention. Hence the book’s title, “once I was you” refers both to an attempt to address young immigrants and young adults pursuing a liberal arts education, and perhaps starting a career in broadcast journalism, and to her ability to speak through this book to her younger, boldly non-conformist and curious, yet also hesitant and self-conscious self. Hinojosa utilizes many of her personal and journalistic experiences as a springboard for revisiting changes in immigration policy, beginning with the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, the repatriation of people of Mexican ancestry (regardless of citizenship status!) in the 1930s, the detention of people of Japanese ancestry during World War II, through to the Immigration Reform and Control Act (IRCA) of 1986 which granted residency to millions of undocumented people, but also led to immigration raids on places of employment. Much of her investigative work is carried out against the backdrop of the massive “removals” and detentions of children as well as adults in privately-run facilities under Presidents Bush, Obama, and Trump. Particularly helpful is Hinojosa’s recounting of the steps leading to the DREAM (Development, Relief, and Education for Alien Minors) Act, the most important step being that taken by the Dreamers themselves whose demonstration at President Barack Obama’s reelection headquarters prompted the signing of DACA. In terms of her career in media, the book spans the distance, through many loops and circuits, from her early days producing a Latin music show at WKCR in New York City to her work with PBS and podcasts, including one, “Latino U.S.A.” for NPR. During her broadcast career, a few of the organizations she worked for underwent major transitions themselves – CNN from the “Chicken Noodle Network,” as she calls it, to a major commercial news network under Time Warner, PBS from a largely government-funded to public interest network accepting sizeable private donations. Throughout, Hinojosa wisely resists the impulse to present her own professional success – whether measured in awards, such as the Robert F. Kennedy Human Rights Award for Journalism, or in salary, as when she worked for CBS and CNN – as a telos, rather it is a story of self-understanding and personal fulfillment through “street- and community-based, POC-centered…storytelling” (p. 161) that carries narrative weight. In the process, we get the palpable sense that not all news flows effortlessly through media organizations, rather, meaningful stories – the stories that probe beneath the surface, that seek out the reaches of neglected policy, such as immigration reform and the failure to provide sufficient aid to disaster-stricken economies (as in post-1980s Central America), must be fought for. Latino U.S.A., which was designed to “educat(e) the public through journalism and humaniz(e) a critical ‘minority’” (p. 153), would have been taken off the air, were it not for Hinojosa’s not taking “no” for an answer and lobbying then NPR president Gary Knell for its reinstatement. And when she isn’t chosen to work on CBS’ 60 Minutes, a program she had admired since growing up on Chicago’s diverse South Side, she decides to form her own company, the Futuro Media Group to leverage special programs and produce her podcasts.

Occasionally, Hinojosa finds herself working at opposite ends of the media spectrum, which creates some cognitive dissonance, but also a clear sense that it is not always “public” vs. “commercial” that matters, but the scale of the market and access to the hierarchy of decision makers. On her experiences as a Latin music dj at WKCR, she writes: “There was nothing like doing live radio in New York City at night in the 1980s. It was a wild time and people used to call into shows as a way to vent, almost like a rudimentary twitter.” (p. 120) Just as Hinojosa’s intrepid and unflinching spirit is the driving force behind her ability to cover the toughest stories (such as 9/11 in New York City and a family grieving over the beheading of a young U.S. hostage by Isis), it has also meant that some “glass” and Anglo doors have been shut by media executives who, after briefly recruiting her talents, wished to keep news coverage within “safe” bounds. Yet this is also a tale of mentorship – we get to know the “nice white guys,” such as Scott Simon and Jay Kernis who gave Hinojosa her first breaks at NPR and CBS (respectively), Latino public radio producers José McMurray and Vidal Guzmán, and, especially the women who, as her seniors at NPR (Lori Waffenschmidt, Sandra Rattley and Margot Adler) and even a meeting with Supreme Court Justice Sonia Sotomayor, helped her to thrive in what was for many years a middle-class male-dominated industry, whether commercial or public in sponsorship.

As she herself points out, Hinojosa is not the only Latina to make her mark on English-language journalism in the United States – she has been flanked by Latina colleagues who have worked at Newsday, The New York Times, and CNN; however, she is the only one to have worked in both public and commercial radio and television, which enables her to give tough, unflinching insights into the concrete possibilities and constraints pertaining to expression and mobility in each domain. The memoir is written in an accessible, conversational style – one feels the author is taking the reader into her confidence – and it is rendered even more accessible by appearing in a bilingual edition, English and Spanish. It has been meticulously researched and fact-checked, which renders it ideal for use in undergraduate journalism and cultural studies courses.

These days, Hinojosa is the happily independent producer and co-host of two weekly podcasts, the now seasoned Latino U.S.A. and In the Thick, “a podcast about politics, race, and culture from a POC perspective.” As one of the original shows in podcast history, Latino U.S.A. demonstrates how important the format has been to driving a diverse wedge into mainstream public programming, as well as in attracting young, digital-savvy audiences of color off-air. Two recent episodes of Latino U.S.A. convey the power of audio to strike a note of intimacy, and to reveal our humanity even in the most adverse circumstances. “City of Oil” (produced by Andrés Caballero, 8 January 2021) features a young woman activist who is trying to get local oil drilling companies to clean up their act to improve health conditions in her Los Angeles neighborhood; the other, an interview by Hinojosa with Dr. Anthony Fauci (“Dr. Fauci: One Year Into the Pandemic,” 5 February 2021) gets President Biden’s new chief of medicine to speak about what inspired him to go into the public health field while growing up in Brooklyn, and why black and brown people have been so adversely affected by the coronavirus – a choice sound byte of which also made its way onto the following week’s In the Thick. The takeaways from Hinojosa’s memoir? Public funding can help to open the door, but it does not always guarantee diversity or hard-hitting reporting; some of the same hurdles to getting humanly inspired and critical reporting on the air have stayed stubbornly with us for decades, and, if you are an aspiring journalist, find a good mentor, show solidarity, and be hopeful of what you ask for – but ask.