How to Film the Histories of the New World: Re-Envisioning the Past and the Future in Latin American Contemporary Cinema

Today at Mediático, and after a bit of a slight pause, we are delighted to present an essay on ten Latin American films which reimagine the region’s past by Natalia Christofoletti Barrenha a film researcher and programmer in Latin American cinema. Dr Christofoletti Barrenha is currently a Visiting Researcher at the Univerzita Komenského v Bratislave, with the support of the National Scholarship Programme of the Slovak Republic. She is the author of the books Espaços em conflito. Ensaios sobre a cidade no cinema argentino contemporâneo (Intermeios, 2019) and A experiência do cinema de Lucrecia Martel: Resíduos do tempo e sons à beira da piscina (Alameda, 2014. Translation into Spanish: Prometeo, 2020) and co editor of Refocus: the Films of Lucrecia Martel with Julia Kratje and Paul Merchant which is forthcoming from Edinburgh University Press (2022).

How to Film the Histories of the New World: Re-Envisioning the Past and the Future in Latin American Contemporary Cinema

by Natalia Christofoletti Barrenha

Every history is a fiction created from specific interests. Its fictional ethos, however, is often overlooked by its narrators, who strive to legitimise their histories and give them the status of truth. The official history is a fiction, built and disseminated by those in positions of power until it becomes part of common sense and is incorporated into memory, daily life and, finally, people’s identities. The construction of official history gives visibility to certain events while hiding others in the sense of creating linear and cohesive narratives that provide support for specific ideas. Therefore, an ‘update’ of the history also responds to agendas of the present that organise the inclusion and exclusion of settings, bodies and voices.

In the last decade, several Latin American filmmakers have been depicting the colonial pasts of their countries in films that differ from traditional historical cinema. Lucrecia Martel, Lisandro Alonso, Niles Atallah, Ciro Guerra, Rodrigo Reyes, Adirley Queirós, Lívia de Paiva and Elena Meirelles’s recent films are part of a revisionist trend which questions and subverts Latin American hegemonic histories through fantastic readings, delusional resources and deliberate narrative gaps. These films oppose those that have tried to adhere to or seek precision in official histories. Many of these films react to works produced from the 2010s in the wake of the bicentenary celebrations of independence in the region—which, despite attempts at greater inclusivity of previously forgotten characters and struggles, and the support of leftist and popular governments, reproduced typically colonised and colonising notions of national progress and manifest destiny.[i]

Of these films that attempt to rework the past, Zama (Lucrecia Martel, 2017), is perhaps the most well known. Based on the homonymous novel by Antonio Di Benedetto published in 1956, Zama takes place in the late-18th century, and focuses on Don Diego de Zama, a white corregidor born and bred in America who serves at the whims of a foreign crown while dreaming of leaving that ‘despicable end of the world’. Martel emasculates, ridicules and decentres her protagonist in an undetermined location that roughly equates with the current border between Argentina, Brazil and Paraguay. Although seeking to subvert its central tenets, Martel does not completely misrepresent the historical setting. In Zama she faithfully reproduces multiple elements of the colonial world (such as etiquette, hierarchies, bureaucratic structure, and clothing, etc.). However, she also profoundly destabilizes that world, mixing the colonial nonsensical elements, distorting the colonial world to a point where everything, including the heavy wigs worn in the heat of the tropics, appears absurd.

Zama proposes a daring hypothesis about the region’s colonial past in its denaturalising of the certainty of colonial power. The film does this in part through the way it centres on the pitiful Zama who is supposedly a figure of power, but at the same times shows around the edges of the frame a multitude of Indigenous and enslaved Black people. These characters, who are mostly appear in domestic roles, and are sometimes mute and headless as a result of the way shots are composed, are nevertheless shown to move in Zama’s world more resourcefully and successfully than the film’s anti-hero. The film also denaturalizes colonial power in its representation of the enivronment, which is conveyed more aurally than visually. Zama is a voyeur (mirón: it is the first thing we know about him), but he is not able to see the most obvious things, while the blind Indigenous people, the animals and the children can contemplate that world deeply. Access to alternative ways of ‘seeing’ is key in the film.

At the same time, this colonial world that Zama presents, although nonsensical and apparently remote in a temporal sense, has not completely ceased to exist. Zama reveals patriarchal and racial relations that continue to figure in contemporary society—relations that Martel explores in her previous features The Swamp (La ciénaga, 2001), The Holy Girl (La niña santa, 2004) and The Headless Woman (La mujer sin cabeza, 2008), which are all set in a middle class Salta (northern Argentina) of the present or recent past. Zama presents a deliberately anachronistic mise-en-scène, and a temporal organisation that challenges a teleological, evolutionary and linear time. Zama proposes instead a circular, repetitive, cyclical time that matches more closely with Native American conceptions of time: one that moves in cycles and spirals, that sets a forward course yet also continually returns to the same point (Rivera Cusicanqui, 2010: 54-55). In this time, there is no ‘before’ or ‘after’, and both past and future are contained in the present—regression or progression of the past, and a sense of the past being repeated or overcome, is at stake in every situation and depends on our actions.

This cyclical conception of time is a feature in other recent Argentine films: Jauja (Lisandro Alonso, 2014) and The Movement (El movimiento, Benjamín Naishtat, 2015). Jauja is another enigmatic work that adds to Alonso’s already quite cryptic filmography. It follows the Danish Capitan Gunnar Dinensen on his journey through an undetermined place which is probably the Argentine Patagonia, where he is tasked with leading the ‘advance of civilisation’. The narrative begins during the Conquest of the Desert, a military campaign directed in the 1870s by the national government in Patagonia, then inhabited by Indigenous peoples. When Dinensen’s daughter runs away with a mestizo soldier, the film becomes a dreamlike adventure that brings together diverse times, geographies and encounters. The film seems to invite a number of different interpretations and also a central question. Firstly, its title Jauja may refer both to the first political centre of the Spanish colony in America (before Lima), but also figuratively to a mythical land of happiness and plenty. Secondly, the contradiction the film presents between the visually empty spaces and the invisible presences that harass from off-screen, synthesises a vision of the conquest: that there can be both a denial of the native inhabitants and a simultaneous order to despatch and destroy them. How does one reconcile the image Jauja offers of a Promised Land with its simultaneous implied genocide?

In The Movement (2015), Benjamín Naishtat deepens his obsession with the various forms of violence that permeate Argentina’s political history, the subject of all his films so far—History of Fear (Historia del miedo, 2014) and Rojo (2019). The Movement follows an unhinged leader, known only as Señor, and his entourage who travel the country committing acts of gratuitous violence and seeking (or forcing) support for the ‘movement’. Unlike Jauja, The Movement firmly establishes the era and the setting of the action (1830s, at the ‘dawning of the nation’), through lighting, dialogue and costume. Despite all those elements, Señor’s long speeches which condemn the state for its corruption and abandonment of the country, and harangue the people to join his movement, echo both the empty and authoritarian political discourse of both contemporary Argentina and Latin America and of 19th century caudillos. This anachronism is made explicit when, towards the end of the film, a motorcycle and a car pass behind the peasants speaking to the camera. The director seems to suggest that the violent past that gave birth to the nation continues in its present.

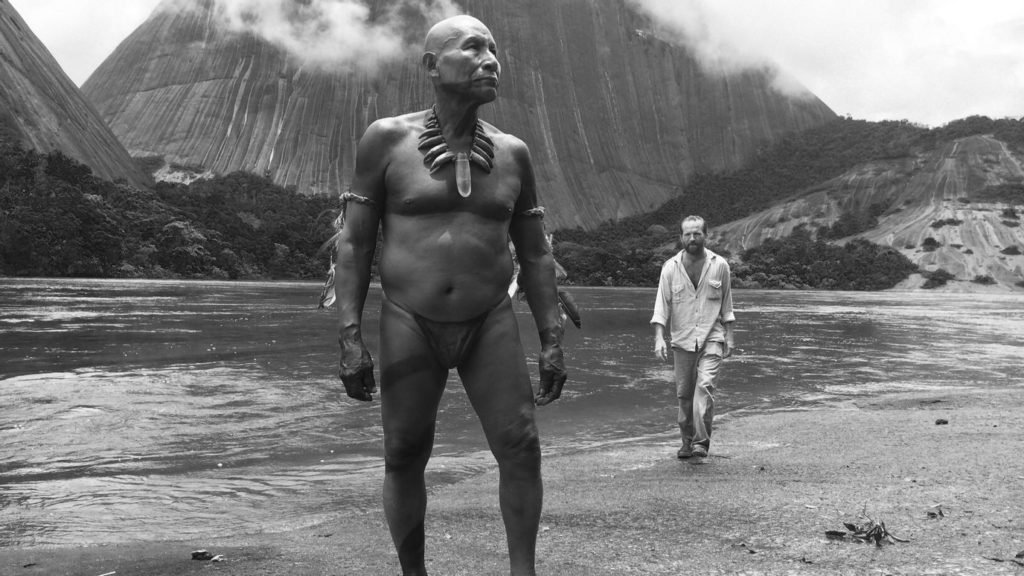

Like The Movement, the Colombian film The Embrace of the Serpent (El abrazo de la serpiente, Ciro Guerra, 2015) takes place not in the early post colonial period, but later, at the turn of 20th century. Diaries of two Western researchers and explorers who travelled the Amazon region half a century apart inspired the plot. The film unites the two experiences around the shaman Karamatake, a character with mythological features and the only survivor of a people devastated by the rubber war, missionaries and famine. In two distinct timelines, which alternate continuously, Karamatake guides the researchers through the dense jungle in search of Yakruna, a magical and medicinal plant. In its title, the film outlines the image of a reptile that moves in a spiral, slowly sliding and undulating, wrapping around its prey in consecutive circles. We discover that ‘the embrace of the serpent’ also refers to the spiritual journey under the psychedelic effects of Yakruna, which transports the imbiber to ancient places and reveals hidden truths. The title also invokes the narrative format of the film that rejects linear temporality and links different cosmogonies, dissolving the authority of the documents the film is based on by putting them in dialogue with fiction and with all who or what were left on the margins of history, such as Indigenous people and even nature.

This reflection on historical documents is further expanded in King (Rey, 2017), by Chilean-American Niles Atallah, who explored the diaries and the judgment minutes of Orélie-Antoine De Tounens, a French citizen who around 1860 proclaimed himself to be the king of Araucanía and Patagonia, an independent Mapuche territory in southern Chile at war with the local government since the end of the Spanish empire (a struggle that continues to this day). King is full of hallucinations and uses striking visual resources that unconventionally portray the fissures of history and memory, through the material condition of the film footage itself. The film was intentionally damaged to achieve an aged effect, and also manipulated and painted extensively (as detailed by the director in interviews with HOME, 2017 and Aguila, 2018). King also contains some found footage. De Tounens’s bizarre saga is framed by the surrealistic dramatisation of his imprisonment and trial by Chilean authorities, who wear papier-mâché masks, and, in the case of one of them, a 20th-century trench coat, reminiscent of Chilean Dictator, Augusto Pinochet. The director does not try to cover the gaps and inconsistencies in the story, but continuously displays them to emphasize the film as an arbitrary and unreliable recounted version of this event.

While Atallah pursues artificial and extravagant aesthetics, Mexican filmmaker Rodrigo Reyes drops a fictional character into a harsh documentary in 499 (2020). An anonymous conqueror from the early 16th century is lost in time and arrives in Mexico in 2020, 499 years after the fall of the Aztec empire, which had paved the way for Spanish dominance. He watches, listens and witnesses Mexico’s violent contemporary reality, and how the exploitative past keeps alive and reproducing, with different tools, the most dreadful faces of conquest: an oppressed people, exodus and displacements, and an economy organised around death.

A new chapter in a brutal colonial project that seems to never end is also the premise of The Devil’s Knot (O nó do diabo, 2018), a Brazilian collective film by Ramon Porto Mota, Gabriel Martins, Ian Abé and Jhésus Tribuzi. Using the framework of the horror genre, the anthology film of five shorts discusses slavery and its inheritances in Brazil, the last Western country to abolish it (just 130 years ago) and with the largest Black population outside Africa. The episodes take place in an old plantation house and its surroundings in five different moments presented in reverse chronological order (from 2018 to 1818). Generations of enslaved and overseers succeed one another, but the owner of the property is always the same authoritarian and bloodthirsty patriarch. The film hinges on a guiding line that runs through it like a reincarnation and the repetition of the same terrors.

********************************************************************************************************************

In many interviews about Zama, Martel has often mentioned the importance of being able to (re)invent the past, given that all current knowledge of it has been passed on by European aristocratic men (Figueira & Lavagnino, 2018; Salvà, 2018). She argues that the same creative freedom commonly employed to imagine the future should also be used to imagine a past that is difficult to grasp, and classifies Zama as a science fiction film.

The American writer Walidah Imarisha has remarked on the power of science fiction (or fantasy, or horror, etc.) in allowing us to contemplate possibilities outside of what exists today, to envision what could be. Imarisha (2015) created the term “visionary fiction” to encompass the fantastical cross-genre creations that help us bring about new worlds, and highlights that this idea is aimed especially at those who have been marginalised, claiming the right to the future for those people whose possibility to imagine it is socially forbidden. She explained: ‘This term reminds us to be utterly unrealistic in our organising, because it is only through imagining the so-called impossible that we can begin to concretely build it. When we free our imaginations, we question everything. We recognise none of this is fixed, everything is stardust, and we have the strength to cast it however we will’ (Imarisha, 2015).

While writing this text, I thought about Imarisha’s concept and how it could be related not only to visionary futures but also to visionary pasts, as Martel proposes, and which could be extended to every work discussed here. Nevertheless, it made me think that, despite the several recent Brazilian films that speculate about the past, it is possible to notice a remarkable number of films dedicated to the future—and to science fiction. At the same time, these films also aspire to change history.

The Brazilian researcher Angela Prysthon (2015: 68) has suggested the expression “realism under erasure” (“realismo sob rasura”) to describe the countercurrent to the realism and minimalism dominant in Brazilian cinema in the 2000s. From the 2010s on, the films have embraced artifice as a strategy, using elements especially from the science fiction genre to generate more ambiguous and thought-provoking narratives, looking for emancipatory aesthetic solutions to political problems. Most works that Prysthon lists were produced by groups working collaboratively within contexts on the margins of the country’s major cultural centres.

Tremor Iê (2019), a collective film with Lívia de Paiva and Elena Meirelles as directors, stands out in this group of films about the future that match with Prysthon’s proposition. Set in Fortaleza, in the stigmatised northeast region of Brazil, the film moves between horror, science fiction and experimental modes to depict a dystopian ‘future’ in which Brazil is under an authoritarian, controlling government with ethnic cleansing policies. Tremor Iê both examines the outcomes of 2013 movements and outlines Jair Bolsonaro’s government discourse and aims even before its rise. Its characters—mostly black women, lesbian, from the outskirts, with non-normative bodies—occupy the empty and nocturnal urban spaces (prohibitive both in the film and in reality, as part of the feminine traumatic and fearful imaginary). There is a mixture of timelines that seems to indicate the perpetuation of oppressive structures that are renovated to continue existing, with the presence of a latent past to which the characters are condemned. Keeping in motion (dancing, cycling, running), in the film, is a kind of resistance to a historically imposed immobilisation. The women also challenge history by stealing the remains of a dictator from a fortified building.

Still further examples of other contemporary films that also match with Prysthon’s proposition are Adirley Queirós’ features White Out, Black In (Branco sai, preto fica, Brasília,2014) and Once There Was Brasília (Era uma vez Brasília, 2017). The filmmaker and CEICINE collective are based and deeply-rooted in Ceilândia, a low-income, working-class peripheral town located in a suburb of Brasília. The national capital is nicknamed the ‘city of the future’ and is widely seen as a landmark in terms of urban planning, yet has also been the target of much criticism regarding segregation and social control. Queirós’s cinematic project reflects upon the tensions between these territories, which synthesises a national history of exclusion, violence and racism.

Both films use a similar narrative trope: a time-traveller arrives from the future to save Brazil in a tense and crucial moment of its history, but he is lost in time. In White Out, Black In, Queirós adds to this tale the memories of a police shooting at a Black dance party in Ceilândia in the 1980s that injured two of his friends—and non-professional actors in the film—Marquim (in a wheelchair) and Sartana (in need of a prosthetic leg). They currently plan to drop a musical bomb on Brasília, where they are forbidden to enter because they do not have a passport, conveying a sense of apartheid experienced on this border. In Once There Was Brasília, the intergalactic agent WA4 should have killed President Juscelino Kubitscheck at the inauguration of Brasília in 1960, but he arrives in Ceilândia during the coup against Dilma Roussef in 2016. He ends up joining a rebel army that intends to destroy the monsters that inhabit the National Congress.

Queirós’s films have been labelled ‘archival fictions’ (Gomes, 2018: 24) and ‘sci-fi documentaries’ (Carréra, 2018: 354). The narratives are anticlimactic and the time is hybrid, malleable, and we can be in the 1950s, in 2016, in 2070, or in all of them simultaneously—there are infinite possibilities. Fiction merges with official history (photos, audio, ads) to show its arbitrary character, putting both the past and the future in dispute, while calling for action in the present. Brasília is always emphasised as a monument to historical erasure, while Ceilândia is placed as a pole of historical inventiveness. Though the films are impregnated with a certain melancholy and pessimism, the characters do not surrender to defeat, which otherwise encourages them to think of alternative means of acting from a minority position. They insist on living and even dare to dream of taking power.

Zama, Jauja, El movimiento, El abrazo de la serpiente, 499, Rey, O nó do diabo, Tremor Iê, Branco sai, preto fica and Era uma vez Brasília all combine historiographical revisionism with innovative film language to dismantle the still prevalent convictions of the colonial project. The usual solemn, disciplined representation of the past as very epic and very heroic and the unitary, integrating, transcendent or redemptive spirit is eroded, messed with or mocked. Those that look into the future draw up audacious revolutionary scenes, proposing new arrangements and solutions for what seems hopeless. All of them seem to recover Imarisha’s proposal as well as the manifesto ‘The Aezthetyks of Dreaming’ (‘Eztetyka do sonho’), presented by Brazilian revolutionary filmmaker Glauber Rocha, in which we read: ‘Breaking with colonising rationalisms is the only way out’ ([1971] 2016).

This article expands on ideas I first explored in ‘Five South American Movies that Decolonise the Imagination’, published in Are We Europe – The Colonialism Issue, n. 9 (December 2020). Available at: https://www.areweeurope.com/stories/south-american-movies.

References

Aguila, Marisol (2018). ‘Entrevista a Niles Atallah. “Rey es el viaje hacia el interior del espíritu o el alma de un fantasma”’, El Agente Cine, 18 January 2018. Available at: http://elagentecine.cl/entrevista/entrevista-a-niles-atallah-rey-es-el-viaje-hacia-el-interior-del-espiritu-o-el-alma-de-un-fantasma/.

Carréra, Guilherme (2018). ‘Brasília Amidst Ruins: The Sci-Fi Documentaries of Adirley Queirós and Ana Vaz’, Aniki. Revista Portuguesa da Imagem em Movimento, v. 5, n. 2, pp. 351–377. Available at: https://aim.org.pt/ojs/index.php/revista/article/view/380.

Figueira, João Vitor and Ana Beatriz Lavagnino (2018). ‘Lucrecia Martel sobre Zama: “É muito importante fazer filmes históricos mais parecidos à ficção científica”’, AdoroCinema, 29 March 2018. Available at: https://www.adorocinema.com/noticias/filmes/noticia-138940/.

Gomes, Juliano (2018). ‘Um ligar à sombra’, in Natalia Christofoletti Barrenha (ed.), Um lugar ao sol. A cidade em disputa no cinema brasileiro contemporâneo. Catalogue of the homonymous film festival that took place at Centro Cultural São Paulo, 7-12 August 2018, pp. 23–27. São Paulo: Buena Onda Produções. Available at: http://buenaondaproducoes.com.br/pdfs/CATALOGO_UMLUGARAOSOL.pdf.

HOME Artist (2017). ‘Niles Atallah Interview’, Glasgow Film website, 22 December 2017. Available at: https://glasgowfilm.org/latest/community/niles-atallah-interview.

Imarisha, Walidah (2015). ‘Rewriting the Future: Using Science Fiction to Re-Envision Justice’, Bitch Media – Law & Order Issue, n. 66 (Spring 2015). Available at: https://www.bitchmedia.org/article/rewriting-the-future-prison-abolition-science-fiction.

Prysthon, Angela (2015). ‘Furiosas frivolidades: Artifício, heterotopias e temporalidades estranhas no cinema brasileiro contemporâneo’, Revista ECO-Pós, v. 18, n. 3, pp. 66–74. Available at: https://revistaecopos.eco.ufrj.br/eco_pos/article/view/2763/2340.

Rivera Cusicanqui, Silvia (2010). Ch’ixinakax utxiwa: Una reflexión sobre prácticas y discursos descolonizadores. Buenos Aires: Tinta Limón.

Rocha, Glauber ([1971] 2016). ‘The Aesthetics of Dreaming’, South as a State of Mind, n. 8 | documenta 14, n. 3. Available at: https://www.documenta14.de/en/south/891_the_aesthetics_of_hunger_and_the_aesthetics_of_dreaming.

Salvà, Nando (2018). ‘Lucrecia Martel: Los héroes me parecen lo peor de lo peor’, elPeriódico, 19 January 2018. Available at: https://www. https://www.elperiodico.com/es/ocio-y-cultura/20180119/entrevista-lucrecia-martel-estreno-zama-656436

[i] Works including: Hidalgo (Hidalgo: La historia jamás contada, Antonio Serrano, 2010, Mexico), San Martín (Revolución: El cruce de los Andes, Leandro Ipiña, 2010, Argentina), The Story of Artigas (La Redota. Una historia de Artigas, César Charlone, 2011, Uruguay) and Juana Azurduy, Heroine of the Independence (Juana Azurduy, guerrillera de la Patria grande, Jorge Sanjinés, 2016, Bolivia), among others.

[…] How to Film the Histories of the New World: Re-Envisioning the Past and the Future in Latin American…: Mediático presents an essay on ten Latin American films which reimagine the region’s past by […]