Ema: A Premonitory Performance of Fire and Dance

by Laura Hatry*

It’s not likely that Pablo Larraín could have imagined the extent to which Ema would anticipate real-world events when it was released in Venice on August 28, 2019. For his eighth feature film, he had, for the first time, explicitly set his story in contemporary Chile, and among a younger generation, as opposed to his own or to the generation that came before him. His dictatorship trilogy (Tony Manero [2008], Post Mortem [2010] and No [2012]) had focused on the Pinochet era, Neruda (2016) and Jackie (2016) on historical figures, and though El club (2015) was set in Chile, its time and place were never specifically defined. When asked during a Q&A in Toronto following a screening of Ema about this aspect of “looking almost to the future,” he answered that, for him, it was more like the immediate past, given that it was already in the process of taking place. Nevertheless, the notion of looking to the future has taken on greater weight in view of Ema’s premonitory relationship to the social upheaval that was to erupt in Chile subsequent to the release of the film. Indeed, two of its central motifs, namely fire and dance, turned out to be focal points of the so-called estallido social during the fall of 2019: arson was ubiquitous, and the validity of its use during the protests was hotly debated, while the performance piece “Un violador en tu camino” became an international feminist anthem.

The estallido social began with a seemingly “innocent” decision: a fare increase on the public transport system of the city of Santiago on October 6, 2019. That the increase of a mere 30 pesos during rush hour (from 800 to 830 pesos, or from around $1.13 to $1.17 at the time) would be sufficient reason to protest might strike readers outside of Chile as improbable, but the local – and the bigger – picture was quite different. This was only the most recent in a string of similar increases, and, for a working population already struggling with high public transportation costs relative to income – the average monthly cost of public transportation is 13.78% of the minimal wage – amidst society-wide dissatisfaction with the now decade-long consequences of the end of the dictatorship and inherited neoliberal policies, as well as a rising clamour against Chile’s immense socioeconomic inequality, it became the straw that broke the camel’s back. Following the announcement of the fare increase, hundreds of students organised evasiones masivas (mass turnstile-jumping), leading to clashes with the police, which escalated on October 18, and Sebastián Piñera’s declaration of a state of emergency the following day. Notably, it was accompanied by the imposition of a curfew for the first time during the democratic era for reasons other than natural disaster. Two days later, on October 20, Piñera would give a press conference in which he declared that the country was at war. The next morning Larraín uploaded a black image to his Instagram account with the hashtag #noestamosenguerra. Four days after the start of the upheaval and fifteen deaths later, the Senate rescinded the fare increase.

However, as most protesters described it, “Chile had woken up,” and the flame kept burning. Within ten days an explanatory document by Hans Stange, Antoine Faure, Claudia Lagos, Claudio Salinas, René Jara, and Alejandro Lagos, called Rabia, started making the rounds on social media, informing the world of the injustices to which citizens had been subjected during this period and exposing both human rights violations and state violence. The first image in the document (2019: 10) shows an enormous blaze that couldn’t be more reminiscent of the conflagrations we see in Ema (Figure 1).

Ema is not an easily likeable character, and Gastón may be even less so; after all, they returned their adopted son to the orphanage after he committed horrible acts of violence, although he probably got the inspiration for his actions from Ema and her own obsession with pyromania. But that’s one of the beauties of Larraín’s filmmaking: he compels us to grapple with injustices experienced not only by the righteous, but by problematic characters as well. It’s easy to identify and feel empathy with a “perfect” protagonist, but how do you empathize with someone like Ema? And how should we understand the physical violence committed during the estallido social – can we possibly justify burning down public property, regardless of the injustices that have led to it?[i] But under the oppression of the neoliberal ruling order, some protesters saw no other means of adequately expressing their fury and showing that these unsustainable disparities must cease. Without condoning violence, it remains imperative to try to understand the complex situation from which it arose, as opposed to simply crushing its perpetrators and ignoring the conditions that drove them to their actions – and let’s not overlook the fact that a large part of the upheaval was likely fomented by police infiltrators fanning the flames so as to justify the systematic use of force against the protesters. Images reminiscent of the worst days of the dictatorship emerged in which police used firehoses to disperse protesters. In Ema as well, it’s not only the stream of fire, but also of water that reflects the arbitrary and insuperable prerogatives of power. When Aníbal, a firefighter, teaches Ema how to operate a firehose, we see – we can actually feel – the power in her hands: a force that can be used to extinguish fires both literal and political.

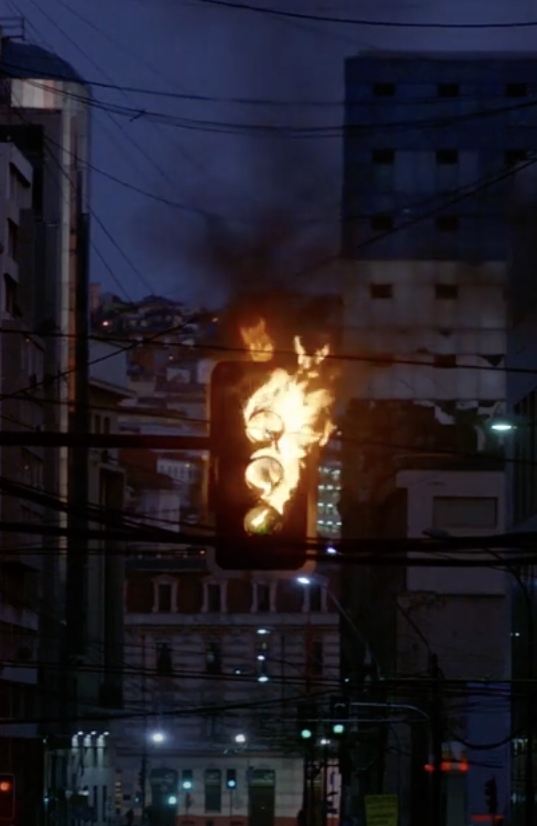

Though they are definitely striking, these images of fire and vandalism reflect just a minor aspect of the behaviour of the predominantly peaceful protesters who took to the streets in their millions. The streets became a canvas for popular protest – and also for wisdom, as Rabia suggests (2019: 31) – filled with banners, spontaneous actions, chants, and performances. Similarly, Ema’s dancing and her nocturnal arson turn into performance art through the lens of Sergio Armstrong’s cinematography. The very first image in the film depicts a burning traffic light, assailing the viewer with scorching rings that might well call to mind another artist who used fire as medium; but where Yves Klein scorch-painted actual canvasses with his flamethrower (Figures 3 and 5),[ii] Ema’s canvasses are the sky and public buildings, a variation on the famous graffiti-covered walls of Valparaíso, according to a comparison by Larraín in the aforementioned Q&A (Figure 4).

If the traffic light is the perfect symbol of order and the set of rules citizens are expected to follow (Figure 6), Ema symbolically sets those rules on fire, challenging a system that, in the words of the social worker who accepted their bribe to enable them to adopt their son Polo, “está hecho para eliminar a gente como ustedes.” The system insists on controlling its citizens, whether by means of the subway fare, biopolitics, organisation of the family, or dominance over the female body.

Ema’s defiance of tradition or conservatism is played out on multiple levels. For one, she questions the “standard,” nuclear, heteronormative family structure, and thanks to a devious plan she eventually succeeds in establishing an eccentric, patchwork sort of family more suited to her values; for another, she severs her ties to the high-brow dance troupe with which she’d been associated. The latter decision is closely connected to her feminism: while Gastón in some ways exemplifies the male gaze when he, the male presence, oversees the performance of his own choreography from the margins, within what we might call the traditional dance circuit, Ema uses dance as a direct form of liberation. First, as a school teacher, she conveys the feeling of freedom to her students by dancing with them, not just observing them as Gastón does, which Larraín underlines visually by showing her among them, kneeling so as to be on the same level.

Second, when Ema and her girlfriends quit the theatre company, they take to the streets, they dance the city, they perform what’s considered low-brow reggaeton – as a minute-long mansplaining monologue by Gastón reveals his traditionalist view on the matter. While his stage performance is drenched in red and blue neon light, their spontaneous outpouring, with the port of Valparaiso as backdrop, establishes a connection in the real world with the two elements these colours represent: fire and water. And it is not just the dancing that makes them feel good on the streets, but more importantly, the female solidarity and friendship, and the fact that “social power arises only through collective action, from a we” (Han 2018: 120). Ema’s girlfriends support her incendiary intentions, and the representation of the intimate moments among them while they dance is simply sublime.

This feminist awakening is inscribed in the larger context of feminist movements in Latin America that started with the famous Ni una menos in Argentina in 2015. But as a direct precedent I would like specifically to mention the 2019 spring issue of Revista Rufián, “El despliegue del fuego feminista,” a title that seems to precisely incorporate the points discussed here and which includes a beautiful photo essay by Paulina Barrenechea that gives an account of the use of fire during the feminist demonstrations in the city of Concepción, Chile, over recent years. The fire that is depicted here, “ruge, activa y […] transforma. El fuego es el conector que permite que el grito colectivo haga tambalear las cortezas patriarcales, la chispa que activa la acción” (2019: 10). These sparks lead us, finally, to the performance by the collective, Lastesis, first staged on November 20, 2019, in Valparaíso, as part of the project “Fuego. Acciones en Cemento.” The choreography of “Un violador en tu camino” and the women calling for rebellion against the “estado opresor,” which is the “macho violador,” perfectly embody Ema’s spirit of burning down the patriarchy. Lastesis and Ema equally conquer the urban space to collectively denounce an oppressive neoliberal, patriarchal system through the power of dance and female solidarity, and with Ema, maybe his most daring film to date, Larraín shows that he is eager to learn from these women who represent the generation of the future.

Works Cited

Cádiz, Pablo. “¿El Metro más caro de Sudamérica? Esto gastan los chilenos en transporte (y qué pasa en el mundo),” T13, October 18, 2019. Available at: https://www.t13.cl/noticia/nacional/evasion-masiva-metro-valor-pasaje-chile-mundo-sueldo-minimo

Carter Jackson, Kellie. “The Double Standard of the American Riot,” The Atlantic, June 1, 2020. Available at: https://www.theatlantic.com/culture/archive/2020/06/riots-are-american-way-george-floyd-protests/612466/

Han, Byung-Chul (2018). Topology of Violence. Trans. Amanda DeMarco. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Reid, Nicky. “A Message Written in Fire: In Defense of Social Upheaval,” Counterpunch, June 12, 2020. Available at: https://www.counterpunch.org/2020/06/12/a-message-written-in-fire-in-defense-of-social-upheaval/

Revista Rufián. Issue 9, number 29, May 2020. Available at: https://rufianrevista.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/Rufian-29-huelga.pdf

Stange, Hans, et al. (2019). Rabia. Miedos, abusos y desórdenes en el oasis chileno. Available at: http://www.luisemiliorecabarren.cl/files/recursos/rabia.pdf

Bio

*Laura Hatry earned her PhD from Universidad Autónoma de Madrid in Hispanic Studies. Her research focuses on cinematic adaptations of Latin American literary works, as well as other convergences (and divergences) among the arts. In addition, she holds an MA in Contemporary Art History and Visual Culture from the Reina Sofía Museum in Madrid and a postgraduate certification in Library Science. She is the editor of Refocus: the Fims of Pablo Larrain (Edinburgh University Press, 2020).

[i] Permit me to recommend this article in The Atlantic or this opinion piece on the subject written in the wake of the protests following the murder of George Floyd.

[ii] You can get a glimpse of Yves Klein’s fire-painting process here.