Dancing Larraín’s Ode to Valpo and Ema’s Very Own Myth of (Re)Creation

By *Philippa Page, Newcastle University

Valparaíso, / qué disparate / eres, / qué loco, / puerto loco, / qué cabeza / con cerros, / desgreñada, / no acabas / de peinarte, nunca tuviste / tiempo de vestirte, /

[…]

el polvo / te cubría / los ojos, / las llamas / quemaban tus zapatos, / las sólidas / casas de los banqueros / trepidaban / como heridas / ballenas, / mientras arriba / las casas de los pobres / saltaban / al vacio / como aves / prisioneras / que probando las alas / se desploman.

Pablo Neruda, from “Oda a Valparaíso”

Pablo Neruda’s evocation of Valparaíso as a mad, dishevelled and poorly clad figure with burnt shoes in some ways finds its embodiment in Ema (2019), the eccentric and seductive (anti-) heroine of Pablo Larraín’s eponymous film. Just as Neruda personifies Chile’s rambling and enigmatic Pacific port in his canto, Larraín makes the city ‘the heart’ of his drama. ‘I think it’s another character of the film’, he noted in a recent interview (2020). Ema marksLarraín’s return to Valparaíso. It provided the setting for a few scenes in his quirky biopic, Neruda (2016), and was the mise-en-scène of his first feature-length, La fuga (2006).

In this, his most recent release, dancer Ema patters to a very different rhythm. But the film remains a fugue of both a visual and musical kind. Larraín’s fluid relationship to genre melds various popular forms with techniques more often associated with auteur pieces. At times, the film feels like a decadent sort of science fiction; at others it has the slickness of a music video; at others the static and very deliberate framing, the sharp and disjunctive dialogue seem part of a comic strip centred around Ema’s quirky flame-throwing superhero-like alter ego. This fusion of styles not only captures the hybridity or palimpsestic character of the location in which the film is set, but it also gives its narrative a ‘polyphonous’ quality that playfully foregrounds the liminal as the space in which the film’s story will unfold.

This reading of Ema suggests approaching the film through the frame of performance. Ema belongs to a dance troupe that is directed by her husband Gastón (Gael García Bernal), a choreographer of contemporary dance and happenings. The group dance routines that are performed at regular intervals throughout the film invite us to look specifically at the meaning that can be traced in the film’s rhetoric of movement (de Certeau 1984: 100). If walking is ‘a space of enunciation’ (de Certeau 1984: 98), the movement of a body that writes itself into the greater urban text, then the corporeal idiom of dance emphasises the film’s peripatetic cartography of Valpo with an intensity and an affective texture of its own, one that gives contour to what might be argued is a structuring tension at the heart of the film’s diegesis between centripetal and centrifugal forces. The clearest example of this is the way in which the characterisation of both Gastón and Ema serves to criticise the conservative, hypocritical authorities that are governing the child adoption service and the public-school system. ‘El sistema está hecho para eliminar a gente como ustedes’, they are told by the corrupt and homophobic agent who arranged their adoption, a poignant statement that goes far beyond reference to the couple’s perceived unsuitability as parents and comments on the systemic exclusion of those who do not fit the productive societal ‘model’ that has been predominant since the dictatorship. However, far from positing a Manichean configuration that contrasts a centrifugal act of resistance with the centripetal forces of authority and normativity, what the film lays bare is the constant tension that exists between these two forces within each and every enunciation (Bakhtin 1981).

Chilean film critic Carolina Urrutia uses the category of ‘centrifugal cinema’ as an organising frame for her recent work on contemporary Chilean cinema (2013). It is important to note, however, that whilst Urrutia’s conceptualisation of the centrifugal offers a fruitful approach to the specific films she analyses, her use of the term is different. She emphasises the ways in which contemporary ‘centrifugal’ films have distanced themselves from the Hollywood narrative mode. Larraín’s relationship to Hollywood and to the establishment is altogether more complex.[i] More instructive here is Mikhail Bakhtin’s use of the term centrifugal, which is seen as inextricably interrelated to the centripetal: ‘Every concrete utterance of a speaking subject serves as a point where centrifugal as well as centripetal forces are brought to bear. The processes of centralization and decentralization, of unification and disunification, intersect in the utterance’, he argues (1981: Kindle Locations 3851-3852).

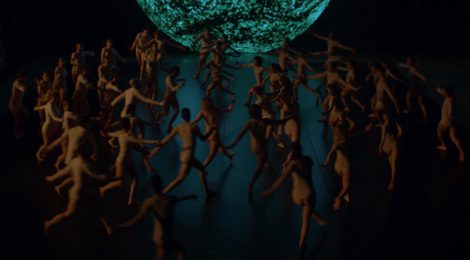

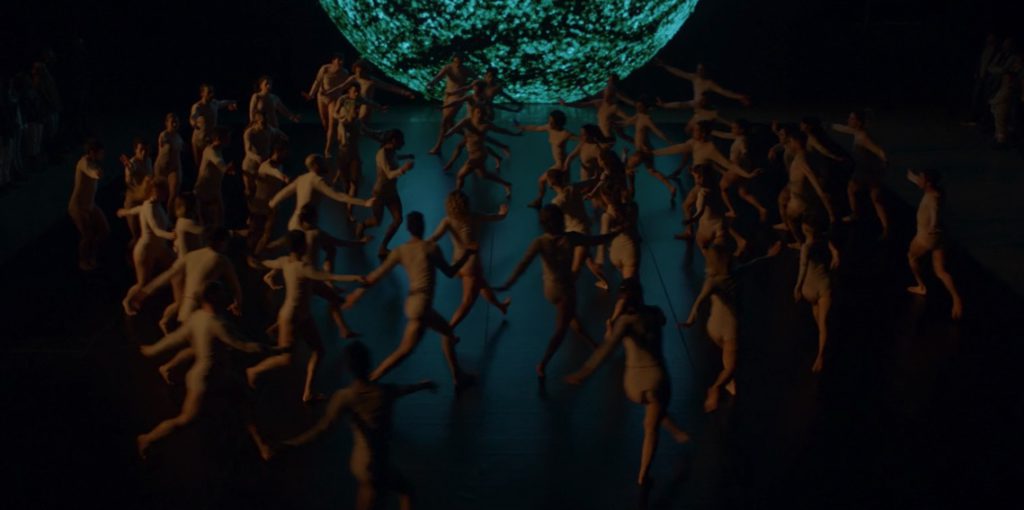

The opening sequence of the film cross cuts between the dance performance that the troupe is currently staging and the calamitous event that has led to the couple giving back their adopted son, Polo. Polo has set fire to his aunt, Ema’s sister, now in hospital recovering. Juxtaposed in dialectic, the fluid, free style of movement typical of contemporary dance might be read as an affective release from the rather static and emotionally contained scenes that are intercalated to depict the drama of Ema’s ailing marriage and her failed attempt at motherhood. Yet, there is something quite Dantean about the tightening circularity that characterises Gastón’s creation as the ring of dancers gradually closes in on Ema, their arms stretching out to grab her and swallow her up as she reaches out in a gesture of escape (Figures 1 and 2). All of Gastón’s performances seem to be characterised by this enclosing centripetal motion, one that we learn must ultimately always revolve around him, the author at the centre. Ema is clearly portrayed as desiring to break free from these centripetal pressures upon her, whether marital or institutional, as captured by the bodies closing in on her during the performance.

Ema looks up towards the projected image of the molten sun behind the dance troupe. She is at the centre of the groups of dancers who reach up trying to grab her as she reaches out from the centre of the circle (Figure 2).

Her childish pleasure in the centrifugal sensation of riding on the carrousel and the spinning teacups during one of her solitary evening ambles around the port area is clear (Figure 3). The sensation of each throws her away from the centre, although never further than the circumference of the circle (still caught inside the ‘discourse of the circuit’?). It might be tempting to read these scenes in relation to what critics have referred to as the ‘aesthetics of disaffection’ (Lie 2018: 13) and ‘detachment’ (Barraza 2015: 442) to describe a series of young people characterised by ‘a lack of enthusiasm and even apathy’ (Lie 2018: 13), one that might be read as a rejection (albeit often a very passive one) of the expectations of productivity placed on them by the neoliberal system. Ariel, the protagonist of Alberto Fuguet’s Velódromo (2010) springs to mind on account of his solitary night wanderings on his bicycle. But Ema is not a drifter without aim or affect. Neither is she an automatic writer of the city. She is singularly determined and compelled by a very specific goal: to experience biological motherhood. The line of flight she draws out of the circle is perfectly linear and has a specific goal. The expression and fulfilment of desire is not an end, but a means to reach this goal.

Where the tension between the centrifugal and the centripetal becomes most abrasive, then, is in the film’s rather confusing gender politics. When asked if he considers Ema to be a feminist film, Larraín remarks that: “Ema was shot, written, and directed by men [prominent playwright Guillermo Calderón is the screenplay writer], so I would say that what we intended to do was share a vision on the issue, to express a sensibility and understand how important and strong the role of women in society is”. Ema and her friends exercise their freedom of movement and expression through the carefully choreographed and rehearsed reggaetón routines that they perform in multiple locations around the city. As Ema seeks a palpable connection with the earth, water, fire and the air at various moments in the film, there is something very organic about their embodied narration of the city (Figures 5, 6 and 7). There is a real sense that these young women are remaking the street on and in their own terms. Yet, their choice of dance genre again points to the internal contradictions of this act, one that Gastón is quick to point out. The sorority that forms around Ema finds expression in carefully rehearsed and synchronised dance routines to a genre of music that is known for its violence and misogyny. Ema’s sense of thrill when she launches napalm flames at objects in the city comes from the fact that she imagines that it feels like a male dinosaur’s ejaculation. There is a subversive element to this matriarchal appropriation of the reggaeton genre and Ema’s desire to simulate the sensations of the male body, but Ema’s ultimate goal of finding all the pieces of the nuclear family, which she builds around herself as centre, seems to undermine this. As Ema dances Larraín’s ‘Ode to Valparaíso’, she dances her own very urban myth of creation. This is a myth that is still founded on the necessarily centripetal notion of the nuclear family—albeit with a less orthodox set of members—and a rather normative experience of motherhood. With her magnetic peroxide aura, as Larraín himself suggests, Ema is the sun around whom everyone else must orbit.

*Bio

Philippa Page is a Lecturer in Spanish and Film at Newcastle University. Her research explores expressions of the social imaginary in contemporary film, theatre and literature of the Southern Cone. She is author of the monograph Politics and Performance in Post-Dictatorship Argentine Film and Theatre (Woodbridge: Tamesis, 2011) and co-editor of the volumes The Feeling Child: Politics, Childhood and Affect in Contemporary Latin American Literature and Film (Maryland: Lexington Books, 2018) with Inela Selimović and Camilla Sutherland, and Entre/telones y pantallas. Afectos y saberes en la performance argentina contemporánea (Buenos Aires: Libraria, in press) with Jordana Blejmar and Cecilia Sosa.

Works Cited

Bakhtin, Mikhail. 1981. The Dialogic Imagination: Four Essays. Austin: University of Texas Press Slavic Series. Kindle Edition.

Barraza, Vania. 2015. From “Sanhattan” to “Nashvegas”: The Aesthetics of Detachment in Alberto Fuguet’s Filmmaking. In Hispania, Special Focus Issue: The Scholarship of Film and Film Studies. Vol. 98, No. 3 (September), pp. 442-451.

De Certeau, Michel. 1984. The Practice of Everyday Life. Trans. Steven Rendall. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Lie, Nadia. 2018. The Aesthetics of Disaffection in the Latin American Festival Film. In L’Atlante, (July-December), pp. 13-25.

Urrutia, Carolina. 2013. Un cine centrífugo. Ficciones chilenas 2005-2010. Santiago de Chile: Editorial Cuarto Propio.

[i] Although maintaining his spirit as an independent filmmaker, Larraín also has a foot in Hollywood. In 2016, Larraín released Jackie, a biographical account of Jackie Kennedy in the aftermath of John F. Kennedy’s murder, thus marking his début in Hollywood. He is also set to film Spencer, a portrayal of Diana, Princess of Wales.