Ingobernable: All Past Roads Lead to the Future

Today Mediático is delighted to present an article on the Netflix series Ingovernable by Pablo Zavala, Ph.D. candidate at Washington University in St. Louis. His primary research focuses on the representation of “the people,” broadly construed, in Mexican print culture at the beginning of the twentieth century. His dissertation is titled, “Forging a People: Visual Culture in Mexico’s Magazines and Newspapers, 1917-1960,” and analyzes avant-garde, socialist, communist, governmental, and artistic outlets in their dialogue between civil society, artists, and the State in the (re)presentation of the people, or the masses. His academic work has explored similar connections in film, literature, and in contemporary cases of femicides in Ciudad Juárez and their intermedial representations. His article “La producción antifeminicidista mexicana: autoría, representación y feminismo en la frontera juarense” was published in Chasqui in 2016.

“Ingobernable: All Past Roads Lead to the Future”

by Pablo Zavala

When I first heard about Ingobernable (Ungovernable Ibarra, 2017) I was not immediately drawn to it, largely because of my own lack of fondness for the excesses of the telenovela form. But Ingobernable, is a series which makes evident the value of a popular form like the telenovela and even its radical potential (López 1991: 596–606). Ingobernable the new Netflix series makes use of both the telenovela and the political thriller format. It follows in the footsteps of other Netflix popular Spanish-language series Club de Cuervos (Alazraki, 2015), the first one ever created in that language by the online streaming service and Narcos (Bernard, Brancato, Miro, 2015-). Kate del Castillo, known worldwide for taking Sean Penn to meet the infamous drug Lord known as El Chapo, stars as Emilia Urquiza, the First Lady of Mexico suspected of having killed her husband President Diego Nava Martínez (Erik Hayser). Throughout most of the first season streaming on Netflix since March 24, and already renewed for a second season scheduled to air in 2018, the multiple stories that drive the plot are a combination of Emilia’s flight from all those who are pursuing her –the authorities and the government who have effectively declared her guilty of her husband’s murder–, her attempts to covertly communicate with her children who are under the surveillance of those pursuing her (both whilst at Los Pinos, the Presidential Palace and elsewhere) and her efforts to sort through a web of corruption to find out who killed her husband and why. Alone and friendless, she has no other options than to seek out the help of a group of initially reluctant sympathizers (an ex-con, a computer hacker and an activist/cabrona) living in the Mexico City working class barrio of Tepito.

In addition to the emotional confrontations proper to the telenovela form, Ingobernable makes use of other mainstream conventions: sex scenes, full-on nudity, action-packed chases, shootouts, betrayal and unfaithfulness. Ingobernable has everything a mainstream audience would expect. It is this winning, marketable mix that has made it a success in national markets and internationally.

Ingobernable’s fictional president and primera dama aren’t anything like their real-life counterparts. Emilia is very much ideologically-driven, and Diego Nava – the president – was too, at least until he started to stray. It isn’t that Nava was particularly loved by the people, but Emilia uncovers that he was killed (and she was framed) because of a speech he planned to give outlining a very progressive and left-leaning political agenda. Almost halfway through the season, the viewer becomes privy to just what the speech contained: stopping the war on drugs, closing the southbound borders with the US, cleaning out corrupt governmental agencies and corrupt elements of the army, closing clandestine detention centers, kicking out US agencies from Mexican territory, and ameliorating socioeconomic inequalities. This situation evokes the famous case of presidential candidate Luis Donaldo Colosio who, in 1994, was presumably assassinated by the sitting president because of a progressive speech he gave. Colosio’s speech represented a shift toward the political left, that left ripples both in the collective memory as well as in the future of the country’s politics.[1.Indeed, on viewing the speech, which Emilia has retrieved with great difficulty on a memory card from the hotel room where Nava was murdered, Chela, the activist helping her comments, “They killed Colosio for a lot less.”] It was a subversive, counter-hegemonic speech, reminiscent of the sudden left Mexico experienced toward the middle of the 1930s. Diego’s speech, which, it is suggested, reflects the convictions he shared with Emilia on taking up the presidency and planned to give to win back her love, represents something similar.

It is perhaps surprising that Netflix should take such a controversial topic in Mexico, since it is known that artistic cultural productions that unrealistically portray the Mexican authorities in a good light, do not generally fare well (El Equipo, produced in 2011 and cancelled a few weeks later). But Ingobernable has been a huge success, suggesting that the Mexican consumer may be drawn to the series for other reasons which outweigh the discrepancy between its quasi-laudable political fiction and the brutal, corrupt, and inept Mexican (presidential) reality. I think the viewer is justified in such a judgment. I believe that these other considerations include thinking about the past as a way toward the future; a way Mexico could and should be. The left might win the presidential elections in 2018, just like it was about to do in 2006 in an election largely thought to have been hacked by the right. And even US senator John McCain has anticipated this, when he recently stated that if the left were to win in Mexico, then we would all lose. Ingobernable raises a point that resonates with many viewers. Another consideration to keep in mind is that the nature of the online streaming service has made the audience an international one, and Netflix shows like House of Cards (2013-) have popularized the generic political drama that transcend national issues.

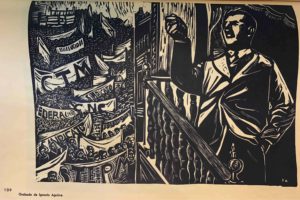

With respect to this notion of past as a way towards the future: I was quite delighted to see that all throughout Ingobernable‘s first season, in the background, the interior of the house at Los Pinos was decorated with artistic prints that I’m studying for my PhD dissertation. The prints were produced by a collective called the Taller de Gráfica Popular (TGP; 1938-1960), and are internationally recognized. (It is not clear whether the actual presidential palace is decorated in this way, although if it were this would be in keeping with Mexico’s history of government sponsorship for even left-leaning artists, examples of which adorn many of its public buildings). For instance, in the office set up for the special prosecutor Patricia Lieberman (Marina de Tavira)– a strong and no-nonsense woman – appointed to investigate Nava’s murder, hangs a print depicting president Lázaro Cárdenas (1934-1940), the most progressive president Mexico has had since the Mexican Revolution (1910-1920):

Special Prosecutor Patricia Lieberman (Marina de Tavira) looking tough, yet idealistic

Ignacio Aguirre. “El presidente Lázaro Cárdenas recibe el apoyo del pueblo mexicano por sus medidas en favor del progreso del país.” 450 años de lucha: homenaje al pueblo mexicano. Taller de Gráfica Popular: Mexico City, 1960.

Cárdenas fulfilled some of the promises of the Revolution, redistributing land to benefit poorer working campesinos, and nationalizing Mexico’s oil industry. The print which hangs over Lieberman’s shoulders in Ingobernable (where Cárdenas is significantly pictured giving a speech), further symbolizes the past-as-future scheme the series seems to insist on; that perhaps, just maybe, we won’t be doomed to live with the neoliberal regimes we’ve had to endure since the early 1990s, and that things could actually go right –or left, rather. And in Ingobernable, it is women (Emilia, Patricia) who are associated with this optimistic change.

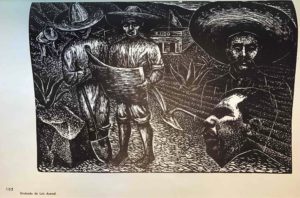

In the office of the lawyer working with Lieberman, Daniela Hurtado (Marianna Borelli), there’s another print of Cárdenas:

Luis Arenal. “Lázaro Cárdenas y la reforma agraria, 1934-1940.” 450 años de lucha: homenaje al pueblo mexicano. Taller de Gráfica Popular: Mexico City, 1960.

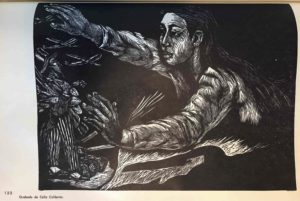

And there’s a print also in the prosecutor’s office where a symbolic woman protects Mexico from the US, an international tension present in the president’s speech:

In Prosecutor Lieberman’s office again, the print is one of an array of Taller Gráfica Popular prints (top left).

Celia Calderón. “La nación no acepta bases extranjeras.” 450 años de lucha: homenaje al pueblo mexicano. Taller de Gráfica Popular: Mexico City, 1960.

Emilia is the driving ideological force behind the speech that becomes the lynchpin of the show. Like the special prosecutor, Emilia is independent and smart. Her character is reminiscent of two other very different characters that del Castillo has recognized as influences for her character: La Reina del Sur’s (2011) Teresa Mendoza, and former First Lady of the United States Michelle Obama. Certainly Emilia’s/del Castillo’s protagonism is welcome in a male-dominated industry (and world). Yet, how Ingobernable (which can also be translated as ‘uncontrollable’) portrays her reminds us of how women have been portrayed in Latin American literature and popular culture, from Santa (Federico Gamboa 1903) and Doña Barbara (Romulo Gallegos 1929) to, precisely, La Reina del Sur, where women, if strong and independent, can be a danger to society as a whole. For the sake of everyone, let’s hope that the second season continues to explore the role of women in uncovering political corruption, and also continues to be a worthy watch.

References

López, Ana M. (1991) ‘The Melodrama in Latin America: films, telenovelas and the currency of a Popular Form,’ in Landy (ed.), Imitations of Life, 596–606.