Latin America’s foremost documentary film festival: É Tudo Verdade (It’s All True) by Stephanie Dennison

Today, Mediático presents an entry from one of its regular contributors, Stephanie Dennison, Professor in Brazilian Studies at the University of Leeds. Dennison is co-author with Lisa Shaw of two monographs on Brazilian cinema (Popular Cinema in Brazil, MUP 2004 and Brazilian National Cinema, Routledge 2007). She co-edited Remapping World Cinema: Identity, Culture and Politics on Film, Wallflower 2006 and Latin American Cinema: Essays on Modernity, Gender and National Identity, MacFarland 2005. She was co-editor of cinema journal New Cinemas (Intellect) 2010-11. She recently edited Contemporary Hispanic Cinema: Interrogating the Transnational in Spanish and Latin American Film, Tamesis 2013 and World Cinema: as novas cartografias do cinema mundial, Papirus, 2013. She is currently working on a collaborative project examining the role of film in the soft-power strategies of BRICS nations.

Latin America’s foremost documentary film festival: É Tudo Verdade (It’s All True)

Now in its 21st year, the international documentary festival É Tudo Verdade takes its name from Orson Welles’ ill-fated and unfinished Brazil-set film It’s All True of 1942, and it claims to be the largest documentary film festival in South America: in 2016 85 films were screened (22 premieres) including a very rich vein of short films which gain much-sought-after Oscar accreditation. Twelve features/medium-length films and eight short films made up the competition list. The São Paulo-based festival was founded and is curated by Amir Labaki, a journalist, film critic and graduate of the University of São Paulo film school. This year the festival was for the first time held simultaneously in the cities of São Paulo and Rio, with the ‘itinerant festival’ currently screening the winning films in Santos, Recife, Belo Horizonte and Brasilia.

The festival opened with Gianfranco Rosi’s Golden Bear-winning film Fuocoammare (Fire at Sea, 2016), filmed over the course of one year on the Sicilian island of Lampedusa, ostensibly “about” the refugee crisis in Europe but much more an exquisitely poetic and honest study of 21st-century island life. Having been new to the festival, I imagined that the choice of Fuocoammare as out-of-competition opener hinted at the kind of aesthetically driven documentaries likely to be favoured by the jury and audiences at the festival: as it happens, I was wrong. Winners of the international and national feature-length competition: Dutch filmmaker Tom Fassaert’s A Family Affair (2015) and Sergio Oksman’s Brazilian/Spanish and Goya-winning O futebol (2015) respectively, are both pretty straightforward first-person documentaries of the type that serve as conduits for the exploration of enigmatic and/or strained family relations. Festival director Labaki points to the familial and autobiographical as being one of the main tendencies in current Brazilian documentary film production, together with biographical studies and historical investigation: all of the Brazilian films, and most of the international productions at the festival this year, fall neatly into these three categories.

Representatives from the State and mixed-ownership companies that regularly support filmmaking in Brazil through government tax incentives (eg BNDES development bank, and the much-malagned Petrobras oil company) queued up at the opening ceremony to say a few politically neutral words behind Labaki himself, and the representatives of the three tiers of government who also sponsored the festival: the municipal and State culture secretariats, and the Ministry of Culture. SP Cine (The São Paulo Film Commission) and the private Itaú bank completed the complex mix of sponsors present at the opening ceremony, which, I was informed, was blissfully much shorter than it has been in previous incarnations. Beyond the ticket-only opening ceremony, at key screenings of Brazilian films (all screenings at the festival are free), and in the presence of the filmmakers, criticisms of the then still impending presidential impeachment process and right-wing backlash against both culture and diversity were openly referenced, to rapturous applause.

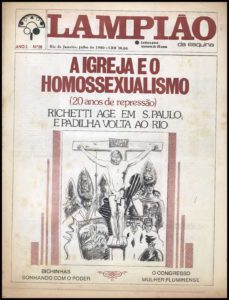

The publication Lampião da Esquina, the subject of the film of the same name

It was interesting to note that Latin American films were highlighted on the programme with their own strand (Latin America, for the purposes of a Brazilian audience, meaning Spanish-speaking America).The important documentary work of Brazilian Carlos Nader was celebrated in a retrospective of the director. But in terms of Brazilian production (the reason I was there), the highlight of this year’s festival for me was the strand “O Estado das Coisas” (The State of Things) and its acommpanying lively round-table debate. There was a real buzz around the screening of Lampião da Esquina (awkwardly translated as Lampiao da Esquina, Lighting Up Brazilian Press), a beautifully crafted overview of 1970s Brazil’s first openly gay satirical magazine of the same name, directed by Lívia Perez, a recent graduate of the State University of Campinas’ film course. And proving that Brazilian documentary filmmakers don’t only make important and revealing films about Brazil, Samir Abujamra screened his O Deserto do Deserto (The Desert of the Desert, 2016), an intelligently observed account of the nation-less Sahawari people, filmed on location in Western Sahara.

A special festival strand in homage to Rio’s hosting of the Olympic Games this August included two excellent French titles: Olympia 52 (Chris Marker’s first feature film of 1954) and Regard Neuf Sur Olympia 52, Julien Faraut’s 2013 film that revisits and thoughtfully contextualises Marker’s original work. The Olympic-related films from Brazil that I caught (Ouro, suor e lágrimas/Gold, Sweat and Tears (Helena Sroulevich, 2014) and Se essa vila não fosse minha/If this town wasn’t mine (Felipe Pena, 2016) were less inspiring: both films played to an almost empty theatre (in the recently revamped but still very seedy Galeria Olido in the downtown area, far from the chic cinemas where the international and in-competition films were screened), and the billed Q and A with Pena simply didn’t happen, without any explanation being given.

Jonas, the star of JONAS E O CIRCO SEM LONA

I began my É Tudo Verdade experience with Fuocommare and the carefully observed detail of the life of a Sicilian boy coming to terms with both adolescence and the promise/threat of seismic changes to his way of life. I ended it once again in the company of an adolescent, whose life had been studiously observed by novice filmmaker Paula Gomes: Jonas, of Jonas e o Circo Sem Lona/ Jonas and the Backyard Circus, 2015, is most definitely a star in the making, with incredible camera presence, if not raw circus talent. The story told by Gomes, of a boy from Salvador, Bahia, born into a circus family who struggles to keep the popular cultural tradition alive while coping with his family’s demands that he take advantage of the opportunity to study, felt to me to be every bit as urgent as Rosi’s critique, given the threat to both culture and creativity that current obscurantist tendencies in Brazil represent.

Reference for Labaki on documentaries:

Featured image: http://pipocamoderna.com.br/2016/03/festival-e-tudo-verdade-2016-tera-22-estreias-mundiais/