by Emiliano Treré

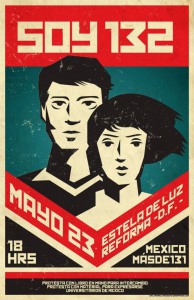

In 2012, after one year as a lecturer in Mexico, an unexpected event changed both the face of the country and the direction of my research. During the national elections in May, the #YoSoy132 movement emerged as a new social actor asking for transparent ballots, denouncing the manipulation of the Televisa media Goliath, and pointing out that the aggressive and deceiving attitude of the PRI party (the party that had ruled the Mexican republic for seven decades and was about to return to power after twelve years under the PAN party) were being replicated again with the new candidate Enrique Peña Nieto. Suddenly, one year after an intense wave of global insurrections, I found myself in the middle of a networked movement where young students were appropriating social media platforms to build counterhegemonic spaces and reclaim media democratization. I have written extensively on the emergence of the movement and its fight for media democratization (García & Treré, 2014, 2015a) and have provided a critical evaluation of its digital media practices (Treré, 2013; Treré, forthcoming 2015b). Here, I will tackle another crucial concern for people interested in the ways through which communication and protest movements interrelate: the enduring relevance of the dimension of collective identity in relation to internal communicative dynamics.

This topic is at the centre of an article (Treré, forthcoming 2015c), which is included in a forthcoming (August 2015) special issue on Social Media and Emerging Protest Identities that I have coedited with Paolo Gerbaudo for the journal Information, Communication & Society. The contributions of the special issue aim to ‘rediscover’ the issue of collective identity in connection to digital media technologies –social media in particular- arguing that it still constitutes a fundamental, though controversial, concept able to illuminate the manifold ways through which activists come together, and assign meaning to their collective protest endeavours.

This topic is at the centre of an article (Treré, forthcoming 2015c), which is included in a forthcoming (August 2015) special issue on Social Media and Emerging Protest Identities that I have coedited with Paolo Gerbaudo for the journal Information, Communication & Society. The contributions of the special issue aim to ‘rediscover’ the issue of collective identity in connection to digital media technologies –social media in particular- arguing that it still constitutes a fundamental, though controversial, concept able to illuminate the manifold ways through which activists come together, and assign meaning to their collective protest endeavours.

In my article, I draw a distinction between a first and a second wave of social movements and digital media studies, and I outline two main arguments. First, the fact that digital social movement studies 1.0 revealed a vivid interest in the examination of the nexus between collective identity and the internal communicative dynamics of social movements. Second, the point that this kind of interest has progressively vanished in digital social movement studies 2.0 that a) are more inclined to study organizational dynamics, technological affordances and transnational connections; b) tend to privilege the data that can be collected on the ‘external spaces’ of social media platforms (Twitter streams, Facebook posts, YouTube videos, etc.), neglecting internal communicative dynamics. The ‘big data’ revolution has strongly affected social movement studies, to a point where scholars have became almost obsessed with the gathering of data on what, borrowing Goffman’s terminology, I call the ‘frontstage’ of social media platforms, neglecting everything that is taking place in the ‘backstage’, such as for instance discussions within Facebook closed groups and chats, Twitter direct messages, and instant messaging conversations. Relying on an extensive two-years ethnography of the #YoSoy132 movement, my article shows the important role of backstage communication practices in the processes of proclaiming, reclaiming and maintaining the collective identity of the movement.

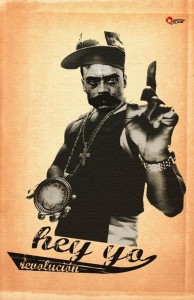

Within Facebook chats and private groups, through the continuous exchange of pictures and memes of revolutionary figures such as Emiliano Zapata and Subcomandante Marcos complemented with ‘incitement texts’ that connected the present situation to the injustices of the past, activists urged to follow the path of past revolutionaries for a real change, and reminded themselves of the historical role they were playing in the Mexican scenario. While these pictures and memes were also widely shared on the social media frontstage, they acquired a particular significance for identity reinforcement within backstage spaces, since they were usually targeted to smaller collectives and groups with a higher degree of intimacy that resembles the functioning of small email lists (Kavada, 2009). Through these practices, activists constituted their collective identity by connecting together different events in space and time into a relevant ‘protest puzzle’ that assigns continuity and coherence to the present struggle and allows the movement to present itself not as some disenfranchised actor, but as heir of the values and ideals of a long tradition of protest.

Within Facebook chats and private groups, through the continuous exchange of pictures and memes of revolutionary figures such as Emiliano Zapata and Subcomandante Marcos complemented with ‘incitement texts’ that connected the present situation to the injustices of the past, activists urged to follow the path of past revolutionaries for a real change, and reminded themselves of the historical role they were playing in the Mexican scenario. While these pictures and memes were also widely shared on the social media frontstage, they acquired a particular significance for identity reinforcement within backstage spaces, since they were usually targeted to smaller collectives and groups with a higher degree of intimacy that resembles the functioning of small email lists (Kavada, 2009). Through these practices, activists constituted their collective identity by connecting together different events in space and time into a relevant ‘protest puzzle’ that assigns continuity and coherence to the present struggle and allows the movement to present itself not as some disenfranchised actor, but as heir of the values and ideals of a long tradition of protest.

Another example is constituted by WhatsApp group exchanges that came to constitute digital comfort zones where activists could “feel comfortable, open up to comrades about personal feelings” (Elisa) , constituting safe places where activists could express themselves far from the “official lights of Facebook walls and pages” (Ernesto). The more personal and intimate environments of the digital backstage were filled with humour. While the jokes spread on the social media frontstage were “directed towards famous, recognizable, public people” (Andrea), the parodies circulated in the backstage were directed at the same members of the movement participating in the discussions, and they thus constituted acts of ‘self-mockery’ (Anna). Through these practices, Mexican activists would reinforce their belonging to the group, showing that they shared “a common code” (Maria) and “a similar understanding” (Cecilia). Furthermore, the critics expressed to comrades through digital satire also performed another function, namely to “lower the intensity of protest” (Mónica).

These findings highlight the vital role that “ludic activism” (Benski et al, 2013) played in connection with internal communicative dynamics to lower the costs of activism in relation to fatigue, reinforce internal cohesion (Romanos, 2013), and foster collective identity processes (Flesher Fominaya, 2007) through the common codes of the digital Mexican generation. In this work, I rediscover the crucial linkage between collective identity and internal communicative dynamics, and show that social media represent not only the organizational backbone of contemporary social movements, but also the multifaceted environments where the new ‘communicative grammar’ of contemporary protest is forged and appropriated.

These findings highlight the vital role that “ludic activism” (Benski et al, 2013) played in connection with internal communicative dynamics to lower the costs of activism in relation to fatigue, reinforce internal cohesion (Romanos, 2013), and foster collective identity processes (Flesher Fominaya, 2007) through the common codes of the digital Mexican generation. In this work, I rediscover the crucial linkage between collective identity and internal communicative dynamics, and show that social media represent not only the organizational backbone of contemporary social movements, but also the multifaceted environments where the new ‘communicative grammar’ of contemporary protest is forged and appropriated.

References

Benski, T., Langman, L., Perugorría, I., & Tejerina, B. (2013). From the streets and squares to social movement studies: What have we learned?. Current sociology, 61(4), 541-561

Flesher Fominaya, C. (2007). The role of humour in the process of collective identity formation in autonomous social movement groups in contemporary Madrid. International Review of Social History, 52(S15), 243-258.

García, R. G., & Treré, E. (2014). The #YoSoy132 movement and the struggle for media democratization in Mexico. Convergence: The International Journal of Research into New Media Technologies, 20(4), 496 – 510. DOI: 10.1177/1354856514541744

Kavada, A. (2009). Email lists and the construction of an open and multifaceted identity: The case of the London 2004 European Social Forum. Information, Communication & Society, 12(6), 817-839.

Romanos, E. (2013). The Strategic Use of Humor in the Spanish Indignados Movement. 20th International Conference of Europeanists. Amsterdam.

Treré, E. (2013). “#YoSoy132: la experiencia de los nuevos movimientos sociales en México y el papel de las redes sociales desde una perspectiva crítica”. Educación Social. Revista de Intervención Socioeducativa, número 55, p. 112-121. [#YoSoy132: The experience of the new social movements in Mexico and the role of social media from a critical perspective]. Special Issue Crisis, Social Movements and Social Transformation.

Treré, E. (2015a) The #YoSoy132 movement in Mexico, Available at: http://civicmediaproject.org/works/civic-media-project/yosoy132movement

Treré, E. (forthcoming 2015b). The Struggle Within: Discord, Conflict and Paranoia in Social Media Protest, in Dencik, L. & Leistert, O. Social Media Protest: Contentions and Debates. Lenham MD: Rowman & Littlefield.

Treré, Emiliano (forthcoming August 2015c). Reclaiming, proclaiming, and maintaining collective identity in the #YoSoy132 movement in Mexico: An examination of digital frontstage and backstage activism through social media and instant messaging platforms. Information, Communication & Society, Volume 18, Number 8.

Short bio

Emiliano Treré is Associate Professor at the Faculty of Political and Social Sciences of the Autonomous University of Querétaro (Mexico). He has contributed to digital media theory, social movements studies, and the sociology of communication, in journals such as New Media & Society, Communication Theory, the International Journal of Communication, Global Media and Communication, Convergence, and in edited books in English, Spanish, and Italian. He is coeditor (with Paolo Gerbaudo) of a forthcoming issue (August, 2015) of Information, Communication & Society on “Social Media and Protest Identities”. His works can be found here: https://uaq.academia.edu/EmilianoTreré. Contact: etrere -at- gmail.com

One Comment Add yours