These Mexican Mädchen

Above, a comparative videographic study by Catherine Grant showcasing the repetitions and variations across two sets of corresponding sequences from the three direct film adaptations of Christa Winsloe’s Mädchen in Uniform / Girls in Uniform (aka Ritter Nérestan and Gestern und Heute, 1930-32): Mädchen in Uniform (Leontine Sagan, Germany 1931); Muchachas de uniforme (Alfredo B. Crevenna, Mexico 1951); Mädchen in Uniform (Géza von Radványi, West Germany 1958). *Contains references to suicide

Below, a production and textual analysis of Muchachas de uniforme (Alfredo B. Crevenna) by Roberto Carlos Ortiz situating the Mexican remake of Mädchen in Uniform in the midst of Mexico’s transnational and genre based classical film industry, and also exploring the appeal of its Italian-Polish star Irasema Dilian and the queer pleasures offered by the film.

These Mexican Mädchen

by Roberto Carlos Ortiz

I wanted to delve into the tortured soul of Manuela,

I studied the most difficult angles of the brain

and the heart of that ghostly woman

– Irasema Dilian, 1951

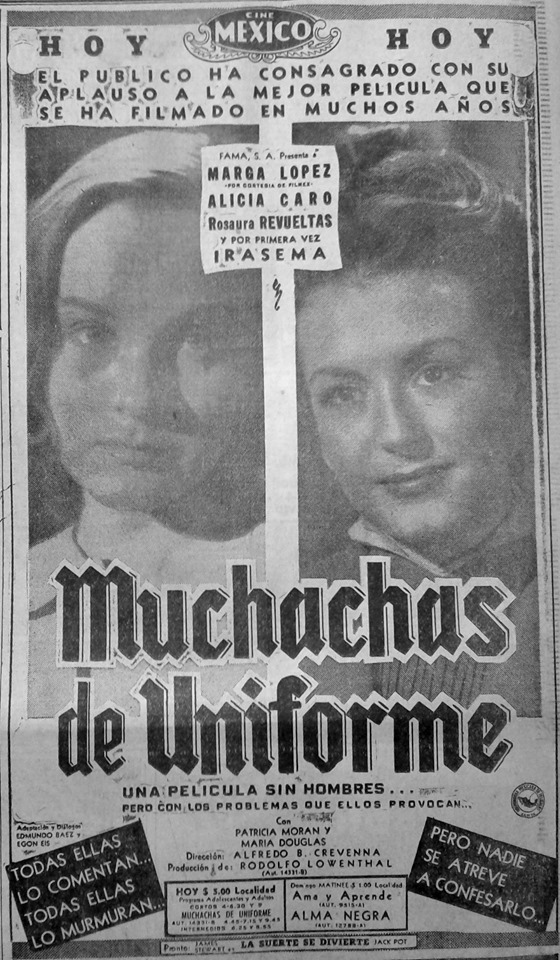

Considered by some as the first Mexican film about lesbianism, Muchachas de uniforme (Girls in Uniform, Alfredo B. Crevenna, 1951) is the little-seen Mexican remake of German classic Mädchen in Uniform (Leontine Sagan, 1931), based on a 1930 play by lesbian writer Christa Winsloe. Set during the last decade of the Porfirio Diaz regime, the Mexican adaptation tells the story of Manuela (Irasema Dilian), an illiterate orphan of unspecified European origin who gets a scholarship by bequest to attend a Mexican convent school. The lay literature teacher Señorita Lucila (Marga López) becomes her surrogate mother figure and the sensitive Manuela naively falls in love with her, under the watchful eyes of the strict Mother Superior (Rosaura Revueltas), the insinuating Mére Josephine (María Douglas) and the snobbish María Teresa (Patricia Moran), niece of her benefactress. Things end tragically when the God-fearing Manuela learns that she has unknowingly sinned by falling in love with Lucila and she jumps from the school’s bell tower to appease her soul. Manuela’s death makes Lucila conscious of her true vocation and the film ends with her initiation as novice.

I became interested in Muchachas de uniforme while researching the career of Irasema Dilian, a mostly forgotten Polish-Italian actress who starred in 1950s Mexican films. The casting of a 26-year-old Spanish-speaking Polish ingénue of Italian cinema, whose name invokes her Brazilian birthplace (to a diplomat), to star in a remake of a German classic of queer cinema struck me as one of the oddest star-making stories in Mexican film history. How did Muchachas de uniforme become the launching pad for Irasema Dilian in Mexico? That question set me on a research path in which the histories of transnational relations and queer images in Mexican cinema intersect.

The main architect behind Muchachas de uniforme was German émigré producer Rodolfo Lowenthal (Rudi Loewenthal), another forgotten figure in Mexican film history who had worked as journalist, publicist, agent and producer in Berlin, Vienna, Sweden, and Paris before emigrating to Havana with help from the European Film Fund. Lowenthal arrived in Mexico City in 1945 and during his brief time in Mexico produced a series of artistically ambitious melodramas most of them based on European texts. Starting with Algo flota sobre el agua (1948), Lowenthal used the creative team of German director Alfredo B. Crevenna (whom he first met in Vienna), Austrian screenwriter Egon Eis (who had also emigrated to Havana) and Mexican writer Edmundo Báez (in charge of dialogues). According to the press, Rodolfo Lowenthal had worked for agent Paul Kohner in Paris and represented Kohner’s interests in Producciones Mercurio, the short-lived production company set up by Dolores Del Rio. Lowenthal took credit for finding, among others, the story that became the Mercurio production La otra (Roberto Gavaldón, 1946) and Muchachas de uniforme was first proposed as Dolores Del Rio’s next Mercurio film.

Some critics have mischaracterized the Mexican adaption of Mädchen in Uniform as a “strange case” (TVUNAM 2018) or “a feat” (Diaz de la Vega 2018) in Mexcian cinema. However, the idea to adapt Mädchen Uniform had precedents in other Mexican productions: ambitious adaptations of European literature as star vehicles, sentimental films set in all-girls boarding schools, melodramas about “sinful women,” and various genres in which a young woman is sent to a convent to keep her away from a suitor (a subplot added to the Mexican adaptation). Mädchen in Uniform was still a long way from becoming an “enduring classic of lesbian cinema” (Film Society of the Lincoln Center 2016) and when the film premiered in Mexico City in 1933, Filmográfico announced it as “a true monument of German cinematography.” Remaking a well-known queer classic would have been audacious, but not the adaptation of an acclaimed film whose censorship outside Germany, through edits and subtitling, had “made the lesbianism a matter of interpretation” (Russo 1987:57). Also, Mexican censorship was laxer than the Hollywood Production Code. Producers were more worried about censorship for political rather than for religious or sexual reasons and being denounced by the Catholic Church could be good publicity (as evidenced in ads during the second week of Muchachas de uniforme’s first run, which asked: “Is this movie immoral or not?”).

When Muchachas de uniforme opened in Mexico City on May 31, 1951 to mixed reviews, filmgoers most likely did not know or remember much about Mädchen in Uniform, but they knew about the stars of Mexican cinema and casting plays a central in the Mexican remake. After producing several prestige films, Rodolfo Lowenthal returned in 1949 to his plans to make Muchachas de uniforme by 1949, but he failed to persuade Dolores Del Rio to play the teacher. In early 1950 Lowenthal cast a younger actress with similar image. Best remembered for playing devoted girlfriends, wives or mothers, Marga López consolidated her stardom with award-winning roles in the melodramas Soledad (Miguel Zacarías, 1947) and Salón México (Emilio Fernández, 1948), in which she played the surrogate mother of her sister. Off screen, López was the glamorous young mother of two boys and El universal ran a column in which she gave advice to mothers. As Carlos Monsiváis notes in her roles: “Marga López, the sweetest, the most understanding, represents kindness defended by an essential purity” (1993:68).

The surprise casting of Irasema Dilian as Manuela altered the focus of the film. Rodolfo Lowenthal reportedly spotted her during a summer 1950 trip to Paris, when he tried to to coproduce Muchachas de uniforme with France. Lowenthal “found his Manuela” in Donne Senza Nome (directed by Géza von Radványi, who would direct the 1958 color remake of Mädchen in Uniform), a co-production about women in a concentration camp. Irasema Dilian played a Polish detainee, a character later described in a way that could apply to her performance as Manuela: “a young girl with an inferiority complex, innocent and pitiful. Her long blonde hair, her eyes without a fixed expression and her slow way of walking, like a tormented soul” (Valdez 1954: 27). Irasema Dilian’s casting became the center of the publicity buildup for Muchachas de uniforme, including pre-production photos of the young actress hanging out in Paris, being welcomed by Jorge Negrete at the Mexico City airport, socializing with her co-stars during a reception at the fashionable nightclub El Patio, and visiting the sets with Lowenthal and Crevenna.

What could an unknown Polish star of Italian cinema signify to Mexican moviegoers? Though the number of Italian films premiered in Mexico City augmented in the late 1940s, they only totaled 29 titles between 1948 and 1950, only one of them with Irasema Dilian: the adventure film Aquila nera (Riccardo Freda). The only other Dilian film shown in Mexico City had premiered in 1948: the Spanish costume film Un drama nuevo (Juan de Orduña). Given the lack of cinematic referents, critics relied mostly on her appearance to judge the newcomer. Efrain Huerta effusively and tellingly described Irasema Dilian as “pale, blonde with light eyes, delicate in body and spirit, with a lucid mind (…) with naturally youthful grace. Europeísima” (1950: 15).

Muchachas de uniforme opens with a Biblical quote that announces a sin: “Let him who is without sin, cast the first stone.” This reference to the tale of the adulterer positions Manuela’s story in relation to empathetic melodramas about sinful women (pecadoras) that had become par for the course in Mexican cinema. In Mädchen in Uniform, Manuela von Meinhardis is a fourteen-year-old soldier’s daughter whose mother has died. In Muchachas de uniforme, Manuela barely remembers her dead mother: a “European” seamstress mother who worked in a Mexican hacienda. When Lucila suggests Manuela might be homesick for her country, she snaps back: “What do I care about my country? I don’t remember it.” If Manuela grew up motherless in a Mexican hacienda, how come she has an accent? Who was her father? Why did her benefactress did not give her an education before? The gaps and contradictions add significance to the image and performance style of Irasema Dilian, a mix of Slavic looks, childlike gestures in the body of a young adult. Manuela is introduced having arrived alone at the school and a schoolgirl comments “You are very odd” (Eres muy rara) before taking her to mass. Manuela speaks for the first time sitting in church. After the schoolgirl asks how she prays to God, Manuela answers in closeup: “I don’t know. I only tell him how I feel.” In her first closeup in a Mexican film, the “europeísima” Irasema Dilian is introduced to audiences like an angelical virginal beauty.

In Mädchen in Uniform, Manuela and Fraulein von Bernburg first meet alone in a staircase and the way they are filmed establishes an erotic attraction even before they exchange words. In Muchachas de uniforme, Manuela and Señorita Lucila meet in an open space (the courtyard), surrounded by nuns and schoolgirls, right after Manuela talks about her mother: “I didn’t know her. She died when I was little.” Manuela cries and screams (“No one has ever loved me! No one!”) when we first hear Lucila’s voice commanding her to stop. The camera moves to the right and Manuela and Lucila share the frame for the first time. Their meeting establishes a distribution of roles: Manuela is the emotional one while Señorita Lucila will react to those emotions with bewilderment (wide eyes), compassion (tender smile) and/or rejection (clenched fists).

There is a narrative need to establish that Manuela’s love for Lucila is potentially sinful while negating the possibility of a lesbian relationship. Manuela evidently adores Señorita Lucila and openly declares her love in the film. However, the script differentiates Manuela’s love for her teacher from the love the other schoolgirls feel for boys, starting with a classroom exchange in which Lucila distinguishes the kinds of love in “amorous” (sexual) and “mystical” (spiritual) poetry, and the possibility of confusing their language. Strategic references to St. John of the Cross and Quo Vadis? establish that Manuela loves Lucila like a figure of religious worship, not as a source of sexual awakening and same-sex desire. This is reinforced by a lack of homoeroticism and female intimacy in the movie, despite the absence of men. In place of the homoerotic atmosphere in Mädchen in Uniform, heterosexual desire lurks around the Catholic boarding school of Muchachas de uniforme through the voices of unseen men (a secret lover, Caruso, serenading students, Lucila’s fiancé). Irasema Dilian and Marga López show no chemistry as a potential couple and it is María Douglas as the inquisitive Mére Josephine who comes across as the queerest character: a potential predatory lesbian who lurks around Lucila (and gets to keep her).

A brief literary reference suggests an additional source besides Mädchen in Uniform. María Teresa, the petulant niece of Manuela’s benefactress, is briefly shown reading Emile Zola’s Nana in bed. There is no basis in Mädchen in Uniform for her character, whose narrative function is akin to the lying Mary in Lillian Hellman’s play The Children’s Hour. After maliciously instigating Manuela’s drunkenness and her “coming out” in the dormitory, María Teresa is the only schoolgirl who knows what is “Manuela’s sin.” Like Mary in the Hellman play, she learns about lesbians through a book, and the choice of Nana equates lesbianism with sexual decadence, prostitution and sin. María Teresa resorts to the school gossip to spread the (unheard) name of the sin among the schoolgirls, leading to a fascinating scene in which Manuela goes around the courtyard asking them to tell her. After learning the name of her sin Manuela is tormented into killing herself. In addition to acting as a catalyst for the resolution, María Teresa’s role reinforces the notion that “Manuela’s sin” was a misunderstanding, a malicious lie.

That negation of lesbian desire does not impede finding queer pleasures in the film. The status of Mädchen in Uniform as classic of queer cinema clearly hovers over our contemporary appreciations, leading some to even see in the remake an openness about female sexuality that does not exist (Filmoteca de la UNAM 2019). Perhaps viewing the film in relation to its German counterparts is the most fascinating way to appreciate Muchachas de uniforme and queer its intended narrative.

REFERENCES

De Caceres M (1951) Irasema en traje de baño no quiere hablar de cine. Cinema Reporter, 16 June.

Diaz de la Vega A (2018) Muchachas de uniforme, a feat of Mexican cinema. Morelia International Film Festival, June 28, https://moreliafilmfest.com/en/muchachas-de-uniforme-una-hazana-del-cine-mexicano/.

Film Society of Lincoln Center (2016) Madchen in Uniform, https://www.filmlinc.org/films/madchen-in-uniform

Filmoteca de la UNAM (2019), https://twitter.com/FilmotecaUNAM/status/1137532832581132289

Elba M (1947) “Algo flota sobre el agua” y sus elementos. Cinema Reporter, 11 October, 38.

Huerta E (1950) Irasema sin uniforme, Lovendal al desnudo. Suplemento de El nacional, 26 November, 15.

“Mercurio” y Paul Kohner con asuntos internacionales (1946). Cinema Reporter, 14 September, 30.

Monsiváis C (1993) Rostros del cine mexicano. Mexico: Américo Arte.

“Muchachas de uniforme” La mejor película del año (1933) Filmográfico, August.

Russo V (1987) The Celluloid Closet: Homosexuality in the Movies. New York: Harper & Row.

TVUNAM (2018) El extraño caso de Muchachas de uniforme. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jdn_oqM38gA

Valdes J (1954) La transformación de Irasema. Ecos de Nueva York, 5 September, 27.

Que buen artículo!