LOS HEREDEROS (The Heirs, Jorge Hernández Aldana, Mexico-Norway, 2015)

Today, Mediático is delighted to present a post on Los herederos (The Heirs, Jorge Hernández Aldana, Mexico-Norway, 2015) by regular contributor Olivia Cosentino a Ph.D student in Latin American Literary and Cultural Studies at The Ohio State University. Her research interests include 20th and 21st century Mexican media and culture, including star studies, youth films, feminism and affect. Follow her on Twitter @occosentino.

Los herederos (The Heirs, Jorge Hernández Aldana, Mexico-Norway, 2015)

by Olivia Cosentino

A preface: Don’t let anyone tell you that Mexicans don’t watch Mexican cinema. It’s simply not true, and frankly, it diverts attention from the larger problems facing Mexican cinema, namely distribution and exhibition. The 7pm Saturday screening of Los herederos that I attended at Mexico’s Cinematheque (the Cineteca Nacional) was packed in an auditorium that houses about 200 people. Smartly made films like Los herederos with deft social commentary are exactly the kinds of films that not only deserve to be analyzed in a blog like Mediático, but also deserve wider distribution and exhibition within and beyond Mexico.

Not to be confused with Eugenio Polgovsky’s 2008 documentary of the same name – Los herederos is Venezuelan-born Jorge Hernández Aldana’s second feature-length fiction film after El noche de la búfalo (2007). Produced by recent Cannes winner Michel Franco and Alex García, a producer who has bankrolled some of Latin America’s biggest hits like Elite Squad (José Padilha, Brazil, 2007), Los herederos joins an impressive line-up from Lucía\Films, a production house that we would be wise to keep an eye on.

Like many Mexican films of the new millennium, Los herederos centers upon youth.[1] It is filled with many established rites-of-passage: learning to drive, drinking, smoking cigarettes and the ins and outs of first relationships. Symptomatic of the post-Y tu mamá también era, Los herederos is marked by fresh Chilango Spanish where “guey” and “no mames” fly about constantly. Throughout the film we follow Coyo, played by newcomer Máximo Hollander, a soft-spoken, upper-class fifteen year old, and his group of equally-privileged friends (including Güeros’ Sebastián Aguirre) as they romp around Mexico City during their Christmas break. After the death of Coyo’s beloved dog Kennedy, he begins to hang out with new friends and test where his boundaries lie. Coyo and three friends shooting a paintball gun in a field quickly turns into shooting at pedestrians and threatening a gas station attendant. This escalates into armed robberies with a real gun and one that ends in tragedy after Coyo (accidentally) kills a man. The rest of the film deals with the aftermath of this violence.

Boyd van Hoeij in the Hollywood Reporter criticized Los herederos for lacking affect and depth and Hugo Lara Chávez in Corre Camara suggested that the film’s “distant and cold characters” “work in detriment to the final result.” I could not disagree more with these two male critics.[2] The true brilliance of Los herederos lies in its detached presentation of violence and the characters’ affectless reactions to that violence, which lead to a chilling indictment of the impunity of the Mexican justice system. Los herederos voices its scathing criticism not only through the narrative, but also affectively by means of sound design and specific cinematographic distanciation techniques.

In a recent article, Laura Podalsky theorizes “an aesthetic of detachment,” which she views in films like Lake Tahoe (Fernando Eimbcke, 2008) and Los bastardos (Amat Escalante, 2009) that “purposefully displace[s] the centrality of characters’ emotional expressivity in fictional narratives and interrupt[s] conventional circuits that encourage spectators’ embodied attachment to the psychic state of particular characters” (239).[3] Podalsky claims that “today’s films” –specifically gesturing towards the new millennium– “wipe away the promise that emotional expressivity can reveal the psychological depth or ‘interiority’ of characters” but instead “they utilize the play between two levels of detachment (within the diegesis and through mode of address) to make the deadening effects of the historical present apprehensible to the spectator in an embodied fashion” (244). It is important to note that detachment occurs not only between the spectator and the characters of the film, but also between the characters within the diegesis.

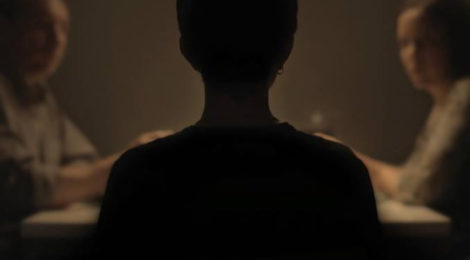

Los herederos undoubtedly operates through an aesthetics of detachment – likely why some viewers and critics have labeled the film “cold” and “unreadable”– by denying the spectator cues from the facial expressions of its characters. Young Coyo rarely shows emotion and speaks in a quiet, monotone voice, both before and after the shooting in the bakery. Podalsky explains that “detachment often emerges in contemporary films through a focus on characters whose facial expressions and bodily gestures do not serve as a transparent register of their psychic state, as revealed through other story elements” (240). Though Coyo does not visibly express his guilt, his insomnia gestures to his emotional turmoil. Furthermore, other crucial moments in the film that should establish tone have the camera positioned behind the characters, refusing the spectator the possibility for the kind of direct connection often available through shots of the actor’s face. A good example of this is the shadowy image of Coyo at the dinner table with his blurred parents that appears on many promotional materials (including the poster for the film which appears in the header image for this review). The film also constantly separates the spectators from Coyo and friends through items of mise-en-scène that obstruct our view. Los herederos codes “youth” as a distant, unknown entity, and subsequently as a privileged, untouchable entity made so through impunity and parental protection.

Los herederos Youth as a distant, unknown entity.

Los herederos highly minimalist treatment of impunity layered with sharp irony gestures to a reality in which wealthy Mexicans escape punishment by literally pointing the finger at poorer Mexicans. When Coyo arrives home after the shooting, he tells his parents that he was robbed at gunpoint and the SUV was stolen. Later that night, in perhaps the most emotional scene of the film, Coyo’s mother leans over his bed and says, “Qué bueno que no te pasó algo / It’s so good that nothing happened to you”. We cringe. A blank-faced Coyo later identifies an obviously innocent suspect and we get a glimpse of the man who will take the fall for this protected youth. After finally confessing to his parents so that he purposefully distances himself from the murder: “Se me fue el disparo y le pegué a alguien / The gun accidentally fired and I hit someone,” the image that immediately follows is Coyo asleep on his mother’s shoulder on an airplane. This fortuitous escape, possible only for mobile, wealthy Mexicans like Coyo and his family, is especially bitter in light of the arduous border-crossing narrative that poorer migrant Mexicans have to endure.

Los herederos Parental protection figures (privileged) youth as an untouchable entity

A final key innovation in Los herederos is the way in which sound design productively accompanies the aesthetics of detachment to definitively condemn violence. Director of sound design José Miguel Enriquez Rivaud inserts bits of soundtrack, sounds which are guttural and synthesized, that are crucial to developing the tone of the film.[4] This electronic, instrumental and visceral music creates an affective, embodied experience of the horrifying reality of impunity. Los heredero’s careful use of sound forces us to reflect upon the morality of evading justice and points to the shared complicity (we all feel that synth in the pit of our stomachs, right?) impunity requires in order to function.

Films like Los herederos point to the fact that critics must consider what minimalism, affectless-ness and sound design can accomplish that sensationalist violence in audiovisual media cannot. We must be careful not to dismiss these new, often unpleasurable aesthetics that seem to have the capacity to reveal nuanced, systemic violence, a beast often immune to representation in contemporary Mexico.

[1] Others Mexican youth films include: Y tu mamá también (Alfonso Cuarón, 2001), Por la libre (Juan Carlos de Llaca, 2001), Drama/Mex (Gerardo Naranjo, 2006), Lake Tahoe (Fernando Embicke, 2008), Voy a explotar (Gerardo Naranjo, 2008), Oveja negra (Humberto Hinojosa Ozcariz, 2009), Despúes de Lucía (Michel Franco, 2012), Club Sandwich (Gerardo Naranjo, 2013), Heli (Amat Escalante, 2013), or more recently Los muertos (Santiago Mohar Volkow, 2014), Güeros (Alonso Ruizpalacios, 2015) and Las elegidas (David Pablos, 2016).

[2] Perhaps Hollywood Reporter’s “bottom line” – “A hardly readable tale of teen violence and transgression” – should clue us in to the complexity of this film, especially for (re)viewers unfamiliar with contemporary Mexico.

[3] Podalsky, Laura. “The Aesthetics of Detachment.” Arizona Journal of Hispanic Cultural Studies 20 (2016): 237-254.

[4] The lack of recognizable songs is significant because Coyo, who frequently wears rock band t-shirts and whose walls are plastered with albums, is defined by his music sensibilities. It would have been a logical choice to include this music, but perhaps that would have interfered with the aesthetics of detachment and gestured towards Coyo’s “interiority.”