Research interest in alternative media has grown considerably over the last two decades in reference to the appropriation of digital technologies for activist purposes, but are we hearing the audience?

The use of social media during uprisings sparked across the world in the emblematic year 2011 (Arab Spring, Indignados, Occupy Movement) onward has largely driven the research focus on the networking of protest movements, assessing the emancipatory or transformative potential of social media activism. Nevertheless, the digital technologies also mediate varieties of activism, including struggles of marginal communities and grassroots activists to reclaim media access, to advance their discourses, and build alternatives to legacy media.

A long tradition of alternative media studies perspective (e.g. Atton, 2002; Downing, 2001; Rodriguez, 2001) has systematically explored alternative media in terms of constituting agencies of resistance, of counterbalancing the unequal distribution of communication resources, regarding their non-hierarchical, non-professional organization, and as locus of empowerment of those engaged in the projects (Vatikiotis, 2005).

A significantly underrepresented aspect in the relevant research has been the alternative media audience/readers/users that John Downing (2003) has eloquently described as “the absent lure of the virtual unknown”; this neglect seems paradoxical considering that “alternative media-activists represent in a sense the most active segment of the so-called ‘active audience’” (p. 625). Both epistemological and methodological concerns restrict scholarship from studying systematically how alternative media texts, programs, posts are received.

First, indubitable assumptions about the role of alternative media in social change, in terms of goal-directed action, have principally privileged the investigation of alternative media producers, examining their motives, strategies and practices. Nevertheless, studies that explore the empowering impact of community/citizens’ media on producers/users’ experience (Gumico Dragon 2001; Rodriguez, 2001) have shifted the attention to processual and relational aspects of alternative media activities, accommodating thus the user perspective. In addition, the renewed interest of social movement studies in the relevance of emotion to mobilization and activism (Goodwin, et. al., 2000) reflects well on a crucial dimension of the alternative media uses, the affective one.

Second, the ‘weak appetite’ of the alternative media sector for information about audience attitudes and beliefs (due to ideological and practical reasons), as well as limitations in research prospects (non-commercial agenda – language, aesthetics) and resources (difficult and time consuming to identify and contact the anonymous and dispersed alternative media audiences/users) set boundaries in probing into the alternative media uses. Paradigmatic exceptions are here Kejanlıoğlu et. al.’s study (2012) on the Independent Communication Network (BIA) and Rauch’s (2007) study on the rituals of consumption and interaction in an alternative media audience.

When it comes to the digital era, new media platforms have provided tools for the expansion of the networked (counter/advocacy) public sphere(s), enhancing participation in alternative media practices and enabling their reach to larger publics. The social web has constituted a vibrant terrain for re-evaluating the aspects of belonging (enhanced by the rise of online interactions that build divergent cultures of communality), representation (enriched by processes of reconstituting subject positions along lifeworld experience), and participation (including aspects of both deliberative and non-deliberative practices, across the public and private realms).

The need to fill the gap in user research of alternative media is critical, considering the conditions of reception in the online environment. People use and experience alternative media in tandem with changing perceptions of space, place and time, along the interplay of the ‘social’ and the ‘digital’; a mediation process that is more fluid, uncertain and complex than in offline times…

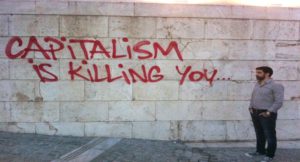

Image belonging to the author.

Against this background, seeking to understand the current state of alternative media, how the latter position themselves in the digital terrain (where the definition of ‘alternative’ becomes even more complicated) and they negotiate, challenge this new source of power (the progressive ‘datafication’ of society) on the whole, we cannot but study consistently users/recipients’ reactions and reflections too. Within the ‘alternative media ecology’ (Lekakis, 2017), which involves the dynamic and complex interplay between alternative media and activism, pivotal is the incorporation of the audience agency perspective in the research and curriculum agendas and in research priorities, in reference to:

-the wide spectrum of alternative media practices (from graffiti to social media), as a whole;

-the infiltration of commercialism into alternative media practices (e.g. last wave of protest movements facilitated by commercial social media platforms);

-hybridization process (e.g. permeable boundaries between mainstream and alternative journalism), and the interplay between alternative and mainstream media uses;

-and, the audience/user’s subject positions across the ‘prosumer’ – ‘produser’ axis.

Pantelis Vatikiotis is an Assistant Professor at the Department of Communication, Media and Culture, Panteion University of Social and Political Sciences in Athens, Greece. His research interests include: sociology of media, alternative media practices, social movements and activism, social media, digital journalism, media and democracy.