Psychoanalytically inspired books and films launched at Birkbeck

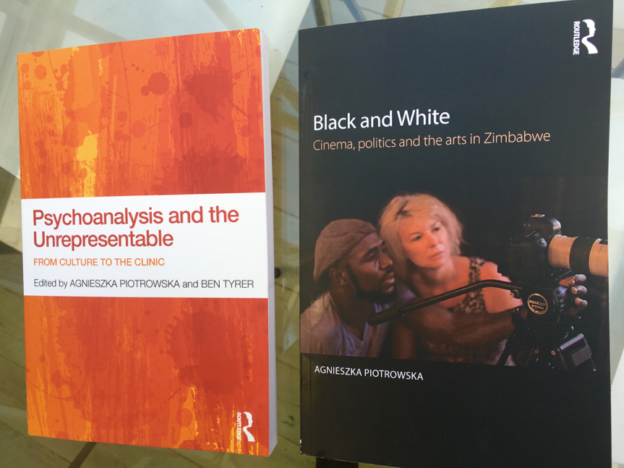

On 18th November at 6pm, Birkbeck Institute for the Moving Image will be showing Agnieszka Piotrowska’s documentary film Lovers in Time or How We didn’t get arrested in Harare (2015), followed by the launch of her book Black and White: cinema, politics and the arts in Zimbabwe as well as Psychoanalysis and the Unrepresentable (co-edited by Agnieszka Piotrowska and Ben Tyrer) both just published by Routledge.

Professor Valerie Walkerdine said the following about the Black and White monograph:

Agnieszka Piotrowska comes to Zimbabwe as ‘the subject supposed to know’ –a position of privilege, albeit unwanted, stemming from her whiteness, undermined by her gender. She interrogates her own experience, attempting to refuse the place of the knowledge, to engage with what it means to tell a story without claiming to know. Beyond black and white, she peers into the grey – the unrepresentable, coming to the recognition that she cannot know, because knowing is so compromised, that engaging with it is challenging, raw, visceral. That she approaches this not knowing through an arts practice is paramount – it is the work together, the embodied creative work of making, that allows the unrepresentable to begin to make its painful emergence. A brave and important book.’-

Valerie Walkerdine, Distinguished Research Professor, Cardiff University, UK

And Professor Caroline Bainbridge noted the following about the The Unrepresentable collection:

This anthology sets out to ‘do the impossible’ in interrogating the paradoxes of unrepresentable and unspeakable experience. Drawing together an impressive array of writers from diverse fields including those of clinical practice, film and literary studies, post-colonial theory and cultural analysis, it weaves a complex matrix of ideas grounded in the work of psychoanalytic thinkers as diverse as Freud, Lacan, Bion, Malabou, Winnicott and Meltzer. The essays are lively and compelling, offering new perspectives on themes such as trauma and embodiment, silence and invisibility in the digital age of media, the psychodynamics of touch, voice, gesture, love, grief, adoption, and anxiety. A wide range of textual material embracing literature, cinema, poetry, language, meta psychology and metaphysics, provides the basis for philosophical and psychological commentary that is often astute, and the daring inclusion of creative work premised on personal experience acts as an emotional coup de foudre. Piotrowska and Tyrer have curated a cracking compendium, one that seduces and challenges in equal measure, and one that will surely become essential reading for anyone interested in the riches of psychoanalytic enquiry.

Caroline Bainbridge, Professor of Culture and Psychoanalysis, University of Roehampton, UK

The event is currently booked out, but please email the organizer Mathew Barrington (mbarri02@mail.bbk.ac.uk) as there may be cancellations.

To coincide with these book and film launches, Reframing Psychoanalysis presents the below text and films by Agnieszka Piotrowska.

By Agnieszka Piotrowska

Below are embedded two short fiction films that I wrote and directed. Both are discussed briefly in the Black and White monograph, but will not be screened at the 18th November event. Both deal with gender relations but also experiment with a filmic language that contrasts rigid ideas and set values with more fluid relations, ones open to new possibilities.

The Suitcase (2015)

Spectacles (2015)

The two short films also subvert the gender expectations in stories–told in Harare–that men are heartless and women powerless. The latter expectation stems also from a Zimbabwean commonplace that it is far better to be married, or at least be with a man of some kind, than single, however painful or destructive the relationship. One could argue that this, too, is part of the colonial legacy and of some of the values introduced by the missionaries: from what we know, the position of a woman in the indigenous culture was very different.

In addition, in terms of its content The Suitcase attempts to subvert the notion that the only stories worth telling from Zimbabwe are those about poverty, HIV or indeed some kind of issues with freedom of speech. Here our protagonists are well off, but tormented, too.

Charmaine Mujeri, whom I met in 2011, and who is a close friend, stars in both films, playing very different characters. She also played the (transgender) Kaguvi in Piotrowska’s earlier film Lovers in Time.

Mujeri found The Suitcase quite difficult as she wasn’t sure conceptually about the notion of throwing a man out just because he had been seen with another woman. But she overcame this uncertainty in her performance. What happened with The Spectacles was a different matter – the leap between the role of a respectable wife and academic to that of somebody who is prepared to consider a love affair with a woman was a profound challenge. During the rehearsals, Kudzai Sevenzo (of the Playing Warriors fame), the actress originally intended to play the younger woman, Clarissa, began to struggle with the notion that two women could become close physically. In the end, the new performer Pauline Gungidza, agreed to play the part. But the kiss that was supposed to happen between the two women never took place as written – there is a suggestion of the closeness but I had to leave the ending ambiguous.

Above: Charmaine Mujeri 2014. Phot. Joe Njagu. C. Agnieszka Piotrowska

In both films the gaze is of crucial importance: in the first one, The Suitcase, the beginning of the film shows Stella (played by Mujeri) receiving a picture on her phone. We never see it but we presume it is a photo of her husband/partner Mark with another woman. The title of Spectacles, refers to the optical glasses that one of the characters wears, but it also clearly points to the issues of looking, seeing and changing perspectives. Below, I offer some psychoanalytical reflections connected to the films.

In Seminar XI Lacan boldly states that the gaze can function as an object – this is a reference from The Visible and the Invisible by Maurice Merleau-Ponty (1964). It is an idea, which becomes central in Seminar XI, that there is a pre-existing gaze in the world. The gaze gives us the distinction between what belongs to the Imaginary order and what belongs to the order of the Real. Antonio Quintet glosses: ‘what corresponds to objet a in the visible is the image of the other. The gaze is not seen because there is something, which covers it over. What hides it is an image – the image of the other (Quintet in Feldstein et al 1995: 140). I have discussed the issues of gaze and structure elsewhere (Piotrowska 2014) but here it was fun to employ fiction and camera to create shifting perspectives and thus different ‘gazes’ and power constellations in gender relations.

Psychoanalyst Carlo Bonomi (2010) reminds us after Lacan of the importance of the ‘gaze’ of the other (Bonomi 2010: 112) which enhances one’s visibility and on occasion can enhance one’s ‘sense of being’ – either through actual actions or through an imaginary relationship to the world. It can be empowering to imagine that somebody we care about is watching us. But, Bonomi points out, there is a possibility that somehow the benevolent gaze might turn into a sinister one. In the shorts, the gaze changes in different ways and certainly for the character of Mark it does become sinister..

Bonomi talks about the risk of being transformed into an object of the gaze of the other. Worse, there is a possibility of suddenly feeling ‘shame’ arising thereof, and causing ‘a sudden collapse of the self provoked by the gaze (…)’ (Bonomi 2010: 113). This happens to the male character of The Suitcase: once he realises that he was ‘seen’ by his partner, the collapse of the relationship and the persona he has created for her is inevitable.

Bonomi gives clinical examples of patients hiding behind dark glasses in order to create safe places, ‘shelters’. ‘Our visibility is dangerous because, in certain situations, when our vulnerability is enhanced, we experience visibility as a threat to the core of our being’. He calls this core ‘soul’ – not perhaps a term which either Freud or Lacan would use [1] and points out defences, which, he says, concern making the body ‘filled with libido and ‘make it thick and real’ like a shield. (Bonomi 2010: 113) When these strategies fail, an individual might feel exposed to the ‘evil eye’ which has links both to Freud’s ‘uncanny’ (ibid.: 113-114) but also to myths and beliefs in non-Western cultures and societies. That disembodied gaze might cause a fear of ‘sterility, disease, and death’ (ibid.: 114). In African cultures, too, one has to be careful of the evil eye.

Further in Seminar XI Lacan shows that the eye as an organ has a fundamental relation to that separation. He gives an example ‘invidia, envy which has it etymological roots in “videre”, to see, and is triggered at an image of ‘completeness closed upon itself’ (Lacan 1998: 116) when the subject gazes at someone else who is in the possession of object little-a. This is a circumstance under which the subject gives to the object an ‘evil look’ which is a fatal gaze symbolizing the separating function of the eye.

Lacan gives an example of a (documentary) film of Cézanne painting which shows it to be, according to him, not the result of a natural action but a terminated gesture – it is the termination of the gesture that produces ‘the fascinatory’ effect (ibid.: 118) as it ‘freezes’ the movement.

Berresem points out that throughout the discussion Lacan plays off the double meaning of fascination as both ‘charming’ as well as ‘putting under an evil spell’. The Latin ‘fascinum’ also means ‘phallus’ or ‘phallic emblem’, which captures its relationship to lack, castration and death (Berresem in Feldstein et all 1995: 177) but also places seeing on the par with the Master Signifier.

In my short films, the gaze, and the moment of seeing, empowers the women, whilst at the same time inflicting pain as something is lost. The gaze does something extraordinary here – it un-freezes them – exactly the opposite of the Lacanian example. Women in both films take power back from a patriarchal order – Lacan might say they gain the Phallus. The seeing camera appears to be disintergrating the world they live in too, particularly in Spectacles as the camera appears unstable, out of focus, unsure – as the world inhabited by the women is falling apart. But something new is beginning to emerge and tboth women begin to see things they did not see before.

The two shorts can be seen as a diptych and have been shown as such at conferences. I felt very unsure about Spectacles because of some technical problems but it appears that it resonates with viewers because of its imperfections.

References:

Bonomi, C. (2010) Narcissism as Mastered Visibility: The Evil Eye and the Attack of the Disembodied Gaze in International Forum of Psychoanalysis, 19, pp.110-119).

Berressem, H. (1996) The ‘Evil Eye’ of Painting: Jacques Lacan and Witold Gombrowicz on the Gaze in R. Feldstein, B. Fink, & M. Jaanus (eds.) Reading Seminar XI. New York: State University of New York Press, pp.149-175.

Lacan,J. (1998 [1981]) Seminar XI. The Four Fundamental Concepts of Psychoanalysis. Miller, J-A. (ed.) Trans. By A. Sheridan. London & New York: W. W. Norton.

Merleau-Ponty, M. (1968 [1964]) The Visible and the Invisible. Trans. by A. Lingis. Evanston, IL: Northwestern Universities Press.

Quinet, A. (1995) The Gaze as an Object in R. Feldstein, B. Fink & M. Jaanus Reading Seminar XI. New York: State University of New York Press, pp.139-149.

Piotrowska.A. (2014) Psychoanalysis and Ethics in Documentary Film. London: Routledge.

[1] Although there is an issue as to how to translate the German word ‘Seele’ which can mean both ‘psyche’ and ‘soul’. Freud uses that word often without defining it. Jung offers a distinction.