Diego Luna’s new Netflix series challenges Mexican stereotypes and presents a radical take on Mexican masculinity

by Deborah Shaw

Today at Mediático and, as a catch up (and heads up) on programmes you may have missed, we are delighted to present regular contributor Deborah Shaw’s take on Diego Luna’s new Netflix series Todo Va a Estar Bien. Professor Shaw has published widely on transnational film theory and Latin American cinema, including The Three Amigos: The Transnational Filmmaking of Guillermo del Toro, Alejandro González Iñárritu, and Alfonso Cuarón (2013) and, most recently, a co-edited (with Professor Rob Stone) anthology, Sense8: Transcending Television (2021).

Diego Luna’s new Netflix series challenges Mexican stereotypes and presents a radical take on Mexican masculinity

The US has a fixation with Mexico on screen. From films like Savages (2012) or Rambo: Last Blood (2019), American dramas insist on presenting its southern neighbour as its negative counterpart. Much research including my own, has explored these stereotypes and distortions and explains how Mexican and Latino men have a long history of being represented in film and television as greasers or bandits, gang members, violent guerrillas, and, more recently illegal immigrants, drug dealers and traffickers.

Sadly, with the repeated production of narco-dramas it seems little has changed in mainstream US takes on its southern neighbour. It is no wonder then that, if we are to believe some of the most extreme of US news platforms, so many US citizens fear Mexicans when films such as Traffic (Soderbergh 2000), Peppermint (Morel, 2018) Sicario (Villeneuve 2015) and Sicario: Day of the Soldado (Sollima 2018) present them with depictions of hyper-violent Mexican criminals. Imagine every US citizen being portrayed in mainstream Mexican film and television as a gun-toting Trump supporter preparing for violent insurrection and you see the problem with this one-dimensional stereotype of Mexicans.

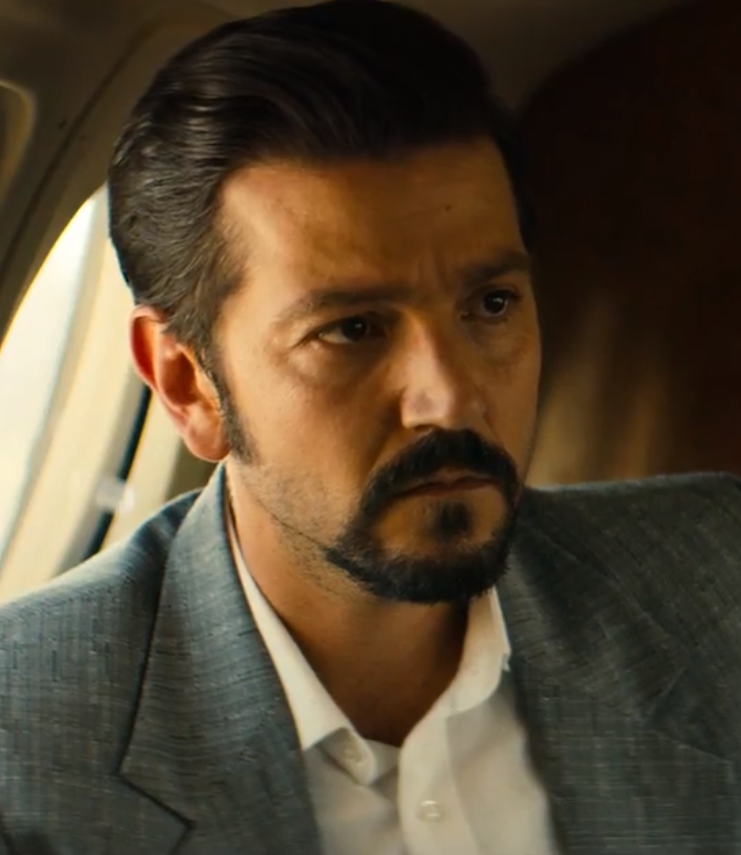

Many know the Mexican actor Diego Luna precisely from this focus on Mexican narco-criminality, among many other roles, as he plays ruthless drug kingpin Félix Gallardo in the US produced Narcos: Mexico. However, Luna’s new show Everything Will be Fine (Todo Va a Estar Bien), that he has produced, co-written and directed, aims to destroy these stereotypes and present a new and more realistic vision of Mexico and Mexican masculinity, without the presence of a single drug dealer or criminal.

## Mexican Machismo

Of course, there are problems with toxic masculinity in Mexico as high levels of gender-based violence and femicide demonstrate. In Mexico, as elsewhere in the world, women have been increasingly active in fighting against machismo, harassment, abuse and violence through the MeToo movement and other forms of feminist activism.

Nonetheless, despite the fact that Mexican machismo exists, stereotypes of Mexican male villains as circulated in the media, do not help to effect change, and have little bearing on reality for most Mexicans. Change is more likely when Mexicans see themselves, that is, people like them, represented on screen. As Luna argues through his new series, men need to reflect on structural patriarchy and alter their behaviours. Everything Will be Fine is a thoughtful and radical series about the complexities of relationships and marriage in an era of feminism and MeToo, and is fundamentally about how men and a patriarchal society have to change.

The series tells the story of a married middle-class couple in the process of separating; they are radio presenter, Ruy (Flavio Medina) and feminist designer, Julia (Lucía Uribe). Their relationship is falling apart, but they share a love for their young daughter Andrea (Isabella Vasquez Morales), who shares an uncanny resemblance with Luna himself. Julia has started a new relationship with a handsome genial dentist, Fausto (Pierre Louis), much to the dismay of Ruy, who initially follows the traditional script for jealous husband.

So far, so conventional, and yet, Luna and his creative team use this premise to raise significant questions in this series rooted in Mexico City, and of relevance to all of us. How can men take responsibility for their deep-rooted patriarchal values in an age of MeToo? What is the role of marriage when these values are called into question? Is the monogamous, heteronormative couple viable in today’s society? Are there healthier alternatives that allow women and men to thrive and to escape convention and toxic relationships?

Becoming a New Man

The series works through these questions and doesn’t pretend that there are easy answers. Yet it proposes options that are surprisingly radical. Ruy’s best friend is Raiza (Úrsula Pruneda), a likeable lesbian in a throuple, and she, along with the men’s group he attends, offer the protagonist guidance on how to be a man and how to form a new relationship with Julia in this new Mexico. Raiza teaches Ruy to let go of any sense of ownership over his wife, and opens his mind to non-exclusive, but consensual relationships. The men’s group workshops teach its participants, who are from all walks of life, about consent, respect for women and how to recognise their own sexist behaviours. All the participants express a desire to change, offering hope for a new and better Mexico.

Ruy gains an understanding that, if he is to evolve, radical new ways of thinking and new relationships are required. Yet, as the final episode reveals, individual actions alone are not enough and in effect, the series is calling for a gender and sexual revolution as unless there is a societal change, those who dare to question the norms will be subject to prejudice.

The domestic servant

A thorny question for middle class white Mexicans who aspire to being progressive is their relationship with their often Indigenous domestic servants. I’ve explored how this issue is also tackled in another Netflix-distributed Mexican production, Roma by Alfonso Cuarón. Everything Will Be Fine features Idalia (played by Mercedes Hernández) who has worked for Julia’s family since she was very young. She has more agency than Cleo can ever have in Roma, set in the 1970s of Cuarón’s childhood. The relationship between Ruy, Julia and Idalia is complex as Idalia is dependent on the family and they are dependent on her. Yet chores and spaces are shared and Idalia is not shy to speak her mind. Nonetheless, as the series ultimately recognises, equality in such a relationship is not possible and Idalia will have to leave the family to find fulfilment. She has been saving and building her own house in her village where she is captain of a women’s football team: another stereotype challenged.

Class and ethnicity are thus central in dismantling Mexican masculine structures. While the US film and television industry continues to rely on damaging and offensive stereotypes of Mexicans, Diego Luna’s Everything Will Be Fine presents a thoughtful and radical reassessment of Mexican masculinity. Let’s break our addiction to narco-dramas and give this series a watch.