Made in Chihuahua: Films, Funding and Frontiers in Northern Mexico

Made in Chihuahua: Films, Funding and Frontiers in Northern Mexico

Rebecca Jarman* and Duncan Wheeler**

Today, Mediático is delighted to present a post by Rebecca Jarman and Duncan Wheeler on their British Council funded visit to the inaugural Chihuahua International Film Festival (2018).

Spanning 2700 miles of the US-Mexican border, the Chihuahua desert does not, at first glance, seem to be the most fertile of settings. It’s a deathly backdrop for migrant crossings, a dumping ground for narco-collateral and the scene of femicides, whose numbers have risen exponentially with the industrialisation of Ciudad Juárez. But in this epic stretch of arid land stemmed early forms of filmmaking, predating Hollywood productions, and generating collaborations between the US and Mexico. In 1914, one of North America’s first film stars, Pancho Villa, is thought to have signed a deal with US-corporation Mutual Films, affording them the right to screen his frontier battles to New York audiences. Spectators were treated to snippets of Villa re-enacting his early life as a revolutionary with executions and battle scenes, some re-enacted in better light or on less dusty tracks to make for better visuals. A century later, once again, the desert serves as the setting for new cinematic projects. Since January 2018, the Film Commission of Chihuahua State has facilitated the production of twenty-five films in the region, welcoming directors from the rest of Mexico and other parts of the Americas. This activity signals new signs of life in a barren landscape, buoyed last year with the Netflix acquisition of ABQ studios in Albuquerque – also part of the Chihuahua desert – which has also been met with optimism among investors and policymakers south of the Rio Grande.

Following in the footsteps of well reputed antecedents in Guadalajara (founded in 1986) and Morelia (2003), Chihuahua city hosted its first international film festival in November 2018 as a platform for local talent. This formed part of the ‘Semana de Cine’ – a week of activities for film buffs that also encompassed workshops run by the University of Leeds at the State University of Chihuahua and funded by the British Council. From Yorkshire, we arrived to a mountainous landscape encompassing a built-up city redolent of a mini-Los Angeles, sprawling outwards rather that upwards, and blessed with that pure kind of sunlight that is a dream to visual artists. It seemed a world away from the dull greys and brick reds of our daily routine, but there are more similarities between Leeds and Chihuahua than first meets the eye. Both have been underrepresented in canonical histories of film: the invention of cinema usually credited to the Lumière brothers was preceded by a home movie shot by Louis Le Prince in his suburban Yorkshire garden. In Mexico, like in the UK, regional urban hubs have to compete with the capital for investment, attention and audiences. The feted “tres amigos” – Alfonso Cuarón, Alejandro González Iñárritu and Guillermo del Toro – made their names through recourse to foreign finance channelled through Mexico City. All three Academy-Award winning directors have alternated between English- and Spanish-language filmmaking. The London-based Cuarón leveraged the commercial and critical success of Gravity (2013) to return to the Mexico City of his childhood in Roma (2018), the capital’s distinctive photogenic streets and modernist architecture exploited for maximum effect.

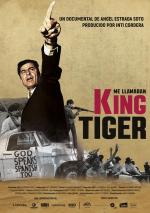

Faced with this competition, Chihuahua has set out to make a name of its own. It is doing so, in part, by capitalising on cultural capital. The idea of ‘regional branding’ was one of the themes that emerged during the workshop, which ran parallel with the Leeds International Film Festival, England’s largest outside London. On viewing the thirty-second promotional video for events in Yorkshire, undergraduates at Chihuahua were quick to pick up on the emphasis on inclusivity among Leeds spectators. They were also eager to stress the potential, as well as the challenges, for their local inaugural film festival to bridge a divisive system whereby attendees at the annual book fair and the popular festivities in honour of Santa Rita, the city’s patron saint, rarely overlap, and where, for the most part, event organizers show little interest in tackling this division. This spoke to a larger issue that cropped up more than once during our visit: that the Mexican films decorated with European awards pull minimal audiences back in Mexico. The Chihuahua Festival logo was of a film reel incorporated into a cowboy’s boot. This gestured towards the integration of production and consumption: a film festival made in Chihuahua for local audiences. But few locals were in attendance at the picturesque out-of-town arthouse cinema for the opening night that premiered They Called Me King Tiger. This was despite the fact that it had been carefully chosen to showcase the real potential of provincial filmmaking.

A feature-length documentary, King Tiger is made by Chihuahua-trained director, Ángel Estrada Soto. It film tells the story of the 1960s Chicano Civil Rights Movement as led by its controversial leader, Reies López Tijerina, and his exploits on the US-Mexican border during the peak of the separationist movement. Incorporating interviews and archive footage, Estrada paints an unflinching portrait of Tijerina, who rallied alongside Malcom X and Elijah Muhammad, and sought to end a regional history of imperial land-grabbing and bloody conflict. His cause is depicted as a just one, but his tactics violent and his relationships abusive: we hear from estranged children, ex-wives and former combatants. In the lighter moments, we were treated to breath-taking shots of visually rich arid scenery, from the deep ochre tones of the mineral soils and bird’s-eye takes of ravenous gullies. Estrada is also sensitive in his film to scenes of human interest. Feelings of sympathy are summoned for Tijerina during his dying days in bed, filmed in 2015 in El Paso. He is accompanied by his third wife, to whom he shows seemingly genuine affection. He looks back on his life with pride, satisfaction and nostalgia. The film is a true accolade to creative initiatives in the region, and a necessary look back at a political struggle that has received scant attention in Anglophone media.

On emerging from the auditorium, we were treated to a spectacular lakeside sundown, before being ushered back into the darkness of the auditorium to view the winning entries for the shorts. A healthier mix of locals, dignitaries and film practitioners arrived to watch this segment. The swanky cinema was full, and buzzing with energy and excitement. The first film was a period drama set in 18th-century Germany, where a young mother trapped in a violent marriage finds hope in her son’s gift as a classical pianist. The latter told a story about a young woman from the Rarárumi indigenous community who disappears after moving to Chihuahua city, and starred two exceptionally gifted young actors from the region. One of the workshop participants was the scriptwriter for this project, and we were pleased to see him receive recognition for his talent and dedication. There followed a reception and lots of photographs on the red carpet. As is case in film festivals the world over, many of the VIPs were parachuted in to hand out business cards and for the purposes of being papped. Especially in the age of social media, the rapid circulation of images from cultural events seems key in generating interest and securing success, and the festival organizers at Chihuahua certainly used this to their advantage.

Still, Mexican cinema is living a special moment that is more genuine than hashtags, comments on Instagram and likes on Facebook. Filmmakers across the country now have greater access to subsidies and tax-breaks than ever before, as well as increased logistical and financial support from local branches of the federal government. This new scenario is a marked contrast to when today’s big names started out in television in the 1990s, and may well have implications for the cultural industries in Britain. Incoming President, Andrés Manuel López Obrador, has pledged more support to the creative sectors but less tolerance of US influence on policy-making and regional development. AMLO, as he is affectionately known, is reputed to be a personal friend of Jeremy Corbyn. Trade agreements with the UK have long been brokered by Europe, but a post-Brexit scenario in which the British Council has prioritised Mexico as a strategic partner makes enhanced links in audio-visual production, distribution and exhibition a credible proposition. It remains to be seen if recent initiatives will transform the desierto chihuahense into a permanent setting for international filmmakers and spectators in a national film industry hitherto dominated by the capital, subservient, in turn, to Sunset Boulevard.

Rebecca Jarman and Duncan Wheeler, University of Leeds

Parts of this article have appeared in The Conversation

* Dr Rebecca Jarman is a Lecturer in Latin American Cultural Studies at the University of Leeds, where she has worked since 2015. In 2016, she received her doctorate from the Centre of Latin American Studies at the University of Cambridge, where she also completed her MPhil (2010-11) and Undergraduate (2005-2009) degrees in Latin American Studies and Modern and Medieval Languages. Rebecca’s research is situated at the intersections between culture and politics in contemporary Latin America, focusing on the conflicts that drive urbanization in diverse geographical and historical contexts. She has published on film from Venezuela and Mexico with the Modern Languages Review and the Bulletin of Latin American Research, and has taught widely in the area of film studies at the University of Leeds, the University of Cambridge and the University of London. In recent months, she has delivered guest lectures and introductory talks at ¡Viva! Spanish and Latin American Festival (Manchester, 2018), and has collaborated with prolific Latin American filmmakers such as Eugenio Polgovsky and Mariana Rondón to showcase public screenings and discussions of their work. Rebecca is also a professional translator and contributes regularly to various outlets of the BBC.

** Professor Duncan Wheeler holds the Chair of Spanish Studies at the University of Leeds. After completing undergraduate (2000-2004) Masters (2004-2005) and doctoral degrees (2005-2010) at the University of Oxford, he was first appointed at Leeds in 2009. Duncan has acted as a programming advisor to the British Film Institute and the Leeds International Film Festival, and amongst his publications on cinema are an edited book titled (Re)viewing Creative, Critical and Commercial Practices in Contemporary Spanish Cinema (2014), a chapter on Mexican and Chilean cinema for the Wiley Blackwell Companion to Latin American Cinema (2017), and an article on the use of film adaptations as a pedagogical device for teaching Spanish classical drama to undergraduate students. In recent years, he has held Visiting Professorships at the Universidad Carlos III, St Catherine’s College (University of Oxford) and UCLA. A published translator, Duncan is the author of two monographs and over thirty peer-reviewed journal articles and book chapters, and is regularly commissioned to write journalistic pieces for such media outlets as The Guardian, JotDown, The London Review of Books and The Times Literary Supplement. In 2016, he was inducted into the Spanish Academy of Stage Arts.