by Alexandra Iliadi*

On 22 April 2016, activists from the Solidarity Initiative for Economic and Political Refugees, a coalition of anti-racist and left collectives, joined with refugees to squat an abandoned hotel in a central district of Athens. The seven-floor hotel City Plaza which had been closed and unused but remained fully equipped for almost seven years is now used to house more than 400 refugees, among whom 180 are children from Syria, Afghanistan, Iran, Iraq, Kurdistan, Palestine, Pakistan and other countries. From the first day until now, the squat is run on principles of self-organization and solidarity and does not receive funding from NGOs or the state.

City Plaza refugee accommodation and solidarity space has emerged as a ‘practical response to the repressive migration and border policies in Greece, the EU-Turkey deal and the militarization of the borders’ as well as state inefficiency in providing humane living conditions for refugees. It is in response to this socio-political landscape that the squatting movement in Greece has shifted its focus to attend to the refugees’ increasing housing needs. In this context, City Plaza chronologically followed the Notara 26 refugee occupation and was followed by other smaller squats for refugee housing, mostly found in the capital’s most political neighborhood, Exarcheia.

However, City Plaza is distinctively different from other refugee squats; while most squats have small presence in the media and are characterized by a lack of communication strategies, City Plaza is the most publicized refugee squat in Athens. Despite the ongoing vilification of the solidarity movement in Greek mainstream press, City Plaza is distinctively and consciously open to the media. Nasim, a key actor in City Plaza, tells me:

This project is not just about us; we want the average citizen to learn about the case.

Media publicity, according to the squatters, is desired for a double purpose; firstly, for the viability of the project itself and secondly for the strengthening of the whole solidarity movement.

A primary benefit which it can offer to City Plaza squat is protection and security. For the activists, the more widespread the case of City Plaza becomes in society and the more the public learns about the decent living and solidarity action in the occupation, the more difficult it will be for the state to target it. Lina from the communication team asserts that

The only way to protect the occupation from possible police raids, evictions and state invasions which aim at “restoring order” is to gain a great deal of publicity and support so that it will not be beneficial for any government to kick us out and to create a network of people who would probably be able to support us in case something like that happened.

Publicity in this context is seen as protection from state intervention.

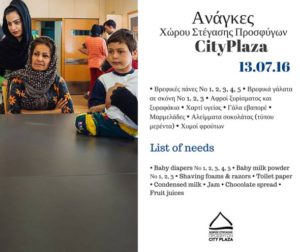

Beyond security, publicity can be particularly facilitating for the occupation’s material reality, namely the everyday running of the project. City Plaza is by far the biggest squat in Athens housing more than 400 refugees. Approximately a thousand meals are prepared daily while residents are provided with hygiene products, milk and medicine weekly. This means that daily costs are immense and support from the public is indispensable for the occupation’s running. Thus, weekly needs are often publicized on social media and the coalition’s blog in order to be met rapidly.

List of immediate needs posted on City Plaza’s blog and social media

City Plaza’s communication to the public serves another crucial role which is not related to the squat’s material presence but is crucial for the fortification of the whole solidarity movement and the incitement of similar acts in Greece and abroad. As Elias informs me, the activists try to maintain a distinctively tolerant attitude towards the media, because:

[…] we want to show to the public what is going on here, since one goal is to help 400 people live here decently. But another goal is to set an example of how the state itself and other people can do things for the refugees and to show that there is a way to house refugees which is human and decent and works better both for locals and refugees…so, this is why we are more open to the media and we are not afraid to be so.

Lina adds that through their tolerant stance to media a positive image can be projected for the whole movement of solidarity with refugees and that through the depiction of local solidarity’s power, the whole society might be urged to a more progressive direction. It follows that the project’s communication works, to draw on her words, ‘propagandistically’, ‘as an example that can help the whole movement’ beyond City Plaza. Decent housing for 400 people is on itself important but, while thousands more are still in camps or on the streets, it is not sufficient. The activists seem to recognize that media are not only important but indispensable in promoting City Plaza as an example that should be followed. Publicity in this context echoes the refugees’ and activists’ political demands to the widest audience possible and encourages similar acts.

Having said all that, an important remark needs to be made in order to avoid techno-determinist assumptions; despite the media’s significance in publicizing City Plaza, the activists do not prioritize media action over traditional forms of political solidarity, like demonstrations. The communication team members are not reserved for media activism; on the contrary they are involved in all traditional forms of political solidarity, from assemblies to protests and mobilizations, which indicates that, above all, they are political activists. The desired publicity is also generated on the streets of Athens through placards, banners and loud slogans which spread the activists’ message in the most direct way. Ultimately, City Plaza is a concrete occupation of space with material needs but at the same time it surpasses its material reality and works as symbol and model for the whole solidarity movement. Both functions reveal the radical potentiality of communication and media publicity. The example of City Plaza needs to be communicated, researched, talked about, and followed.

City Plaza refugees and activists protesting under the banner ‘Open the empty buildings for refugees. Access to health and education- Refugee Accommodation Space City Plaza’, 14 July 2016.

If you want to support or donate to City Plaza visit: http://best-hotel-in-europe.eu/

*Alexandra Iliadi has recently completed her Masters in Media and Cultural studies at the University of Sussex. She is interested in the relationship between media, politics and activism. Her research explores the role of the media in the context of the pro-refugee solidarity movement in Athens in which she is involved at the moment.