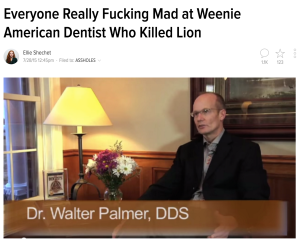

A recent development in the area of digital media and social movements is the use of mediated visibility as a way to shame and deter targeted individuals. Recent examples include the global outrage Walter James Palmer faced after killing a lion in Zimbabwe, as well as groups in the United Kingdom and the Netherlands that publicly identify suspected paedophiles. By spontaneously and autonomously mobilising against such offences, these movements are seemingly informed by non-digital forms of vigilante activity. On first pass, these appear to be a parallel form of criminal justice that undermines the legitimacy of police agencies. Yet the relationship between digital vigilantism (DV) and policing warrants further scrutiny.

While both digital and conventional vigilantism are typically framed as a critical response against the state, DV’s relation to a given state’s socio-political climate is more complex, and often is ultimately supportive of the state and the enactment of law and order. Vigilantism is typically understood as extra-state, popular and extra-legal, yet it takes on “state-like performances such as security enforcement” along with “a perpetual renegotiation of the boundaries between state and society” (Burr and Jensen 2004, 144). Vigilantism does not mark a rupture from state and policing, but rather a renegotiation of acceptable boundaries, to an extent that blurs the boundaries between state and populist action (Lund 2001). Vigilantism in this context involves a criticism of state performance, alongside an alignment with state objectives. While lacking state authorization, vigilante groups “do not perceive their actions as over-riding or transgressing the legal order but construct themselves as self-anointed guardians rescuing national sovereignty, citizenship and the law’s moral sanctity, from cultural elites, moneyed interests, inept bureaucrats and a sclerotic state.” (Walsh 2014, 13).

DV thus raises a curious dynamic in public perception of – and intervention in – policing, as participants may enact national sovereignty and citizenship on digital media that by definition exceed the scope and jurisdiction of any nation. While this complicates attempts by police to investigate crimes through social media (Trottier 2015), users and DV participants in particular may nevertheless expect some kind of (self-)policing of and through these platforms. As many users are immersed in a digital media culture that implicitly or explicitly prescribes self-policing online, the gradual dissolution of online/offline distinctions may lead to users employing a kind of self-reliant approach when embodied crimes and transgressions are mediated (Huey et al. 2012). This dynamic is most notable in cases where the perceived crime retains an online dimension, as in cases of cyber-bullying or revenge porn.

DV complicates citizenship through the blurring of boundaries between police and public, as well as through the enactment of national identities and hegemonic cultural values through digital media. Through mediated and ’glocalised’ (Wellman 2002) outrage and the sustained visibility of perpetrators, DV campaigns exercise a kind of us/them identity reflecting a “hegemonic bloc, rallying conservative factions” within society (Oomen 2004, 155). Conventional vigilantism is typically bound to a single nation, and often reflects nationalist identity building (Kucera and Mares 2013). This can be seen through the use of nationalist and xenophobic rhetoric, for example, white nationalism among Ku Klux Klan members in the United States. Yet due to the coupling of digital media and vigilantism, distance is no longer a barrier in vigilantism or nationalist manifestations (Dennis 2008: 356). The backlash to the 2011 Vancouver riot made a clear distinction between a local ‘us’ based in downtown Vancouver and an outsider ‘them’ relegated to the outer suburbs (Schneider and Trottier 2013), even though participants in the campaign themselves were not geographically restricted. Further, DV campaigns may indeed challenge conventional identity-based movements, such as when Anonymous sought to openly identify a thousand KKK members.

Vigilante groups typically act in defiance of police, and police typically condemn and prosecute vigilante activity. Yet these relations may resemble a more nodal form of governance, for example when Toronto police reach out to DV hacking communities in order to identify those responsible for the Ashley Madison data breach. Such potential partnerships may comply with recommendations that police crowdsource the search for data, but not actual investigations, while others believe that both are feasible with effective safeguards. In either case, the possibility that social actors appropriate police appeals as a means to harm others remains an area of concern. These developments suggest that DV should not be regarded as an aberration from other digital media practices, but instead located on a continuum of forms of user-led policing and citizenship.

Burr, Lars and Steffen Jensen. 2004. Introduction: vigilantism and the policing of everyday life in South Africa. African Studies 63(2): 139-152.

Dennis, Kingsley. 2008. Keeping a close watch – the rise of self-surveillance and the threat of digital exposure. The Sociological Review 56(3): 348-357.

Huey, Laura, Johnny Nhan and Ryan Broll. 2012. ‘Uppity civilians’ and ‘cyber-vigilantes’: The role of the general public in policing cyber-crime. Criminology & Criminal Justice 13(1): 81-97.

Kucera, Michal and Miroslav Mares. 2015. Vigilantism during democratic transition. Policing and Society 25(2): 170-187.

Lund, Christian. 2001. Precarious Democratization and Local Dynamics in Niger: Micro-Politics in Zinder. Development and Change 32(5): 845–869.

Oomen, Barbara. 2004. Vigilantism or alternative citizenship? The rise of Mapogo a Mathamaga. African Studies 63(2): 153-171.

Schneider, Christopher and Daniel Trottier, D. 2012. The 2011 Vancouver Riot and the Role of Facebook in Crowd- Sourced Policing. BC Studies: The British Columbian Quarterly 175(Autumn): 57–72.

Trottier, Daniel. 2015. Coming to terms with social media monitoring: Uptake and early assessment. Crime Media Culture 11(3), 317–333.

Walsh, James P. 2014. Watchful Citizens: Immigration Control, Surveillance and Societal Participation. Social & Legal Studies 23(2): 237-259.

Wellman, Barry. 2002. Little Boxes, Glocalization, and Networked Individualism. In Digital Cities II. Edited by Makoto Tanabe, Peter van den Besselaar, and Toru Ishida, 11-25. Berlin: Springer-Verlag.

2 Comments Add yours