Consumption today overtakes our everyday spaces. Advertising penetrates our vistas. We are increasingly asked to rebrand ourselves, to go on the quest of a better future. We consume material and immaterial objects on a daily basis. Yet, our consumption pollutes our environment, both material and mental, argued Kalle Lasn in his book Culture Jam. Consumer society is no longer a postmodern condition, it is the invisible life-world that we inhabit in the global North.

Consumer society has changed significantly from its post-war booming, no less than by engulfing many of the concerns of civil society and social movements alike. Works such as Samantha King‘s on the corporatisation of breast cancer, Mara Einstein‘s on the commodification of compassion, or Douglas Rushkoff‘s on broader colonial corporatism have revealed the extent to which consumption is manipulated and managed to primarily serve the needs and logics of the economy, rather than those that it claims to cater for. Ethical narratives have permeated the marketplace and have become interwoven with a set of new global responsibilities, which are increasingly and explicitly available in it.

The extent to which our consumption can be turned towards our own common good has come to question repeatedly. Can we relieve through giving, through ethical consumption ? Or can we control our own consumption in order to control our future? For some, we can and should relieve through aid. By donating to charity through direct debit, on the street, at the shop, we are told, we are becoming part of a humanitarian world. By setting money aside ever so often, we are, at least theoretically, engaged in global social change- world betterment even.

For others, we can claim control of our political agency and transfer it to the marketplaces, by tuning in to civic-minded shopping preferences. In this scenario, without setting money aside, but by being selective in our purchases, more often than not in the face of their labeling, we are winning our way to a fairer world. An example of this would be fair trade coffee, for instance. By purchasing fair trade coffee, we are arguably ensuring a fairer world by making sure that producers in the global South earn a fair day’s wage for a fair day’s work. It’s not about aid, it’s about trade. But the roots of trade run deeper than our everyday exchanges with the marketplace. And, as I’ve argued elsewhere, as liquid as coffee is, so are its politics.

Yet, ethical consumption is part of a broader phenomenon which, according to authors such as Micheletti, Stolle and Follesdal, also consists of the denial of consumption of particular brands/ products/ companies because of their unethical practices. Boycotts, in fact, precede by far ‘buycotts’ (ethical consumption) in historical terms, ranging back to at least two centuries. Boycotts are prehistoric denial of service (DoS) attacks, in which people refused to put up with being subjected to those who dominate them. Various examples of boycotts have exhibited themselves historically, ranging from the late 18th century with Boycott British Goods campaigns leading to the constitution of the United States of America, to the Boycott Nestle campaign which has been running since 1977 and is still organised by the International Nestlé Boycott Committee.

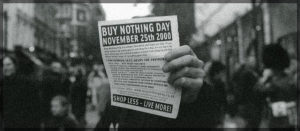

But how deep does a boycott run? The Buy Nothing Day is a type of boycott celebrated on November 28th (Black Friday) in the US, and November 29th (always a Saturday) internationally. The organisers, Adbusters, a co-founder of whom is the author of Culture Jam, began by launching a Buy Nothing Christmas, as the season generates a high peak in consumer behaviour, especially in the US. A Buy Nothing Christmas is, arguably, a step towards the break on the accelerated consumer course of the global North. The idea of a Buy Nothing Day followed that of Christmas, although the second did not disappear. On the contrary, Adbusters have recently rebranded the campaign to ‘Occupy Xmas’, for purposes of resonance with the Occupy Movement. Adbusters share more than a name with the movement, as they designed a now iconic poster, which was the first call to Occupy Wall Street. This goes to show the persistence and political significance of consumption and consumer culture today.

Black Friday is a US invention which describes the Friday following Thanksgiving Day in which consumer heaven (or hell) is brought down to earth for one day only where everything is on sale. This tradition of a consumerist day, one could argue, is a predominantly North American phenomenon. Yet, some (companies, such as John Lewis in the UK) say that Black Friday has become “a permanent fixture on the calendar in the run up to Christmas”; this goes to show that consumerism and its celebrations are not aware of national borders, but carry rejoicing over consumption to a hyper-level. Targeting this hyper-consumerism which anti-consumerist tactics, such as the Buy Nothing Day, is important and doing this on the national level is also significant, as consumption has penetrated culture and symbols of our understanding of consumption are also based on the promotional communication we have been exposed to. Below is an image from the Buy Nothing Day (UK branch), testifying to these reconfigurations of our promotional culture which dictate our consumption patterns.

But how deep can a boycott run? For its critics, Buy Nothing Day means that you are engaging in another form of slacktivism, as you are probably going to buy something the day after. Yet, awareness of the sensitive balance between consumption and our environments is significant. Consumption is not a democratic process by which we can voice our opinion (yay or nay). Consumption is a market-driven process in which we can only choose from a selection of pre-selected choices.