Outing Queer Archives in Mexico City: The “Jotographies” of Agustín Martínez Castro

Today, Mediático proudly presents a broad ranging account of a recent exhibition of the photographic work of Mexican queer artist and activist Agustín Martínez Castro by Mexico City-based independent researcher and Mediático contributing editor Roberto Carlos Ortiz.

Outing Queer Archives in Mexico City: The “Jotographies” of Agustín Martínez Castro

by Roberto Carlos Ortiz

1. Coming Out

Featured Image: Agustín Martínez Castro & María Eugenia Chellet, from the Blue (Azul) series, created by Martínez Castro & Chellet, 1982.[1. Images courtesy of Centro de la Imagen. Many thanks to César González Aguirre and Ana Ocadiz for their help.]

They tell of people who worked and played, who laughed and fought, and who are finally remembered.

– Cindy Ruskin, The Quilt: Stories from the NAMES Project, 1988[2. Cindy Ruskin et al., The Quilt: Stories from the NAMES Project, New York, Pocket Books, 1988, p. 13.]

On April 19, 2018, the archive of images created by Mexican artist Agustín Martínez Castro (1950 – 1992) was “outed” in Pirates on the Boulevard: Public Demonstrations, 1978- 1988, the first retrospective of his work. During a lifetime cut short by AIDS, Agustín Martínez Castro took part in the homosexual liberation movement in Mexico City and created an important archive of images that gave visibility to 1980s LGBTQ activism, theater, nightlife and underground scenes. His “outing” or “coming out” at Centro de la Imagen, where the exhibit ran until July 15, can be linked to the drag tradition that subverted debutante balls to present gay men into society, as channeled through the contemporary practices of queer curators and scholars who rescue, review and engage with the legacies of LGBTQ artists.

Born in Veracruz, Agustín Martínez Castro studied Communications at the National Autonomous University of Mexico (UNAM). In 1978, Martínez Castro met Juan Jacobo Hernández, co-founder of the newly formed Homosexual Front of Revolutionary Action, FHAR, and the next year took his first photos in collaboration with them. In 1979, he also joined the Group of Independent Photographers, formed in 1976 and led by Adolfo Patiño. The 1980s were a period of intense activity in Mexican photography. The intersection of political engagement and art production continued as Agustín Martínez Castro collaborated with different collectives and organizations. He also had a personal network of artist friends and lovers. Martínez Castro’s earlier photos were documentary-style black-and-white images about consumer culture in the city and gay activism, but he soon adopted techniques that broke away from convention, like intervening Xeroxed images from photos taken in 35mm film. In addition to creating images and exhibiting them (mostly in collective shows), Martínez Castro worked as cultural coordinator, promoter, graphic designer, editor, teacher, writer. Despite leadership roles in groups like the Mexican Photography Council (CMF), Agustín Martínez Castro also showed his work in non-traditional places, like the infamous Spartacus gay club. Consequently, he didn’t get the same level of recognition as some contemporaries, especially after his death.

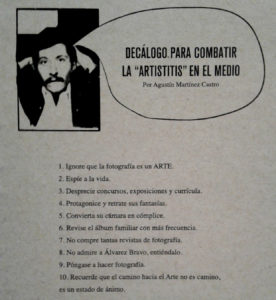

“Decalogue to Fight ‘Artistitis’ In the Field,” 1980.[3. “1. Ignore that photography is an ART.; 2. Spy life.; 3. Disregard contests, exhibits and curriculum.; 4. Be the star of your fantasies and photograph them.; 5. Turn your camera into your accomplice.; 6. Review the family album more often.; 7. Don’t buy so many photography magazines.; 8. Don’t admire {Manuel}Álvarez Bravo, understand him.; 9. Go make photography.; 10. Remember that the road to the Art is not a road; it’s a state of mind.” Originally printed in Artes visuales, n. 25, August 1980. Most translations from Spanish in this article are my own.]

(Reproduction of Martínez Castro text)

The time frame 1978 – 1988 in Pirates on the Boulevard closely links the personal to the political in Agustín Martínez Castro’s artivist work. On October 2, 1978, the first public demonstration by the Homosexual Liberation Movement in Mexico City took place during a non-LGBTQ event observing the 10th anniversary of the Tlatelolco massacre. In 1988, Martínez Castro was diagnosed HIV+ while briefly living in New York City. Curator César González Aguirre , the main orchestrator of the retrospective, was only a toddler when Agustín Martínez Castro died of AIDS-related illness in Acapulco in 1992, at age 42. Pirates on the Boulevard surveys Mexican LGBTQ histories the curator did not experience, during a period distant enough that names, places and actions have been forgotten, yet close enough that major participants are still around to share testimonies as they continue their activisms. This “outing” of Agustín Martínez Castro was an intergenerational rendezvous, in which 1980s images, histories and discourses of homosexual pride conversed with 2010s queer perspectives and curatorial practices.[4. The timing of the retrospective also invited dialogue with parallel exhibits. At Centro de la Imagen, Martínez Castro shared the museum with retrospectives of experimental artists Teo Hernández (1939 – 1992), a gay Mexican filmmaker based in France who also died of AIDS, and Ricardo Valverde (1946 – 1998), an Arizona- born, Mexican-American multimedia artist based in Los Angeles who befriended Martínez Castro’s artist network. Parallel LGBTQ-related exhibits in the city included Laberintos inexplorados. Entre la misoginia y la lesbofobia, showcasing the Historical Archive of Feminist Lesbians in Mexico, and El chivo expiatorio: sida + violencia + acción, addressing AIDS activism in Mexico and containing work by openly HIV artists and activists. There have also been events honoring the forthcoming 50th Anniversary of the Tlatelolco Massacre and the Mexican Student Movement of 1968, events which deeply influenced Agustín Martínez Castro’s generation.]

In Mexico City, like elsewhere, there are competing notions about the meanings and uses of queer (or cuir). Queer may be randomly or rarely used, contested with skepticism, considered foreign, coexist with local idioms, or be adopted by “pink” marketing.[5. “Pink money” (Dinero rosa) was the theme of the 31st International Festival for Sexual Diversity in Mexico City, which also took place over the course of June 2018.] I consider Agustín Martínez Castro’s archive of images and the Pirates on the Boulevard exhibit “queer” in a flexible sense. Queer remains a useful critical position or tool that interrogates and rejects fixed identity categories. However, queer also values and includes – instead of snubbing as outdated or outré – the spectrum of identities in the homosexual liberation discourses of the 1970s, Mexico City’s LGBTTTI acronym and “sexual diversity” approach, and oppositional terms embraced by alternative groups. Queer engagements with the archives unsettle stable narratives, honor intersectionality and urge multiple readings. This type of approach to LGBTQ archives caused controversy in the past. Pirates on the Boulevard thus builds on 2015’s flawed but groundbreaking Dis-closeted Archives: Specters and Dissident Powers, an exhibit which previously brought Mexican LGBTQ archives to the museum.[6. Controversy soon followed the July 2, 2015 opening of Archivos Desclosetados: Espectros y poderes disidentes at Mexico City’s Museo Universitario del Chopo. (“Disclosetado” was translated as “Out of the Closet” at the museum, which missed the Spanish play on words.) Presented in conjunction with the annual International Festival for Sexual Diversity, the exhibit showcased archival materials documenting the histories of Mexico City’s LGBTQ communities. Nina Hoechtl and Naomi Rincón Gallardo’s curatorial stance explained the exhibit intended to be “a mapping through the revisions of collections and archives both public and private, interviews and field research,” structured around the themes of gathering places, activisms and “cultural prosthetics.”]

2. Queer Engagements

Juan Jacobo Hernández and Carlos Toimil, 1979

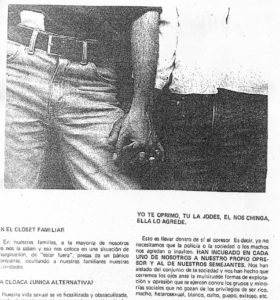

(reproduction of FHAR [Homosexual Front of Revolutionary Action] pamphlet)

The images by Agustín Martínez Castro, like those of his LGBTQ contemporaries outside Mexico, stand out primarily as documents of their time. Echoing the lyric of a famous 1930s Mexican bolero, Pirates on the Boulevard, however, proposed the notion of the “artist as pirate.”[7. The opening lyrics of Agustín Lara’s “Veracruz” (1936) are: “I was born with the silver moon / I was born with a pirate’s soul.” The Mexican composer falsely claimed Veracruz as his birthplace. ] According to the curator, Agustín Martínez Castro produced “pirated images” under the influence of drag aesthetics, breaking with conventional photography techniques and developing his artwork with “one foot in the door of the art institution and a stiletto heel in the life that exists outside of it.”[ César González Aguirre , curatorial statement displayed in Pirates on the Boulevard: Public Demonstrations, 1978- 1988, Centro de la Imagen, Mexico City, April 19 – July 15, 2018.] By directly connecting Martínez Castro’s “pirating of images” to Mexican LGBTQ activism and culture, Pirates on the Boulevard contests earlier (brief) assessments that presented the artist as just a chronicler of “the world of transvestism” who “turns us into voyeurs of an unimagined culture.”[9. Roberto Tejada, “Tríptico urbano,” La ciudad: tres puntos de vista, México, D.F.: Universidad Autónoma Metropolitana, 1993. Quejada’s text shows the language used in the 1990s to value gay artists (without describing the artist as such): “gay semiotics,” “camp,” “transvestite parody.”

The notion of Agustín Martínez Castro as chronicler was repeated in América Latina Photographs, 1960 – 2013: “His images give a true account of underground urban life in Mexico in the 1980s.” Paradoxically, the catalog features images from Expediente 13 (File 13), a series in which Martínez Castro’s interventions of Xeroxed images of tabloids points to their artificiality. Carolina Ariza, “Agustín Martínez Castro,” América Latina Photographs, 1960 – 2013, Puebla, Mexico: Museo Amparo & Paris: Fondation Cartier, 2013: p.198-199.]

Before facing the first Agustín Martínez Castro image, visitors at Centro de la Imagen are met with an acrylic painting by Antonio Salazar (1956 – 2016)[10. Antonio Salazar co-founded and coordinated the Taller de Documentación Visual (1984 – 1999), an important collective whose artwork intersected art, AIDS and activism.] titled For a Socialism Without Sexism, 1984-90, one of the main slogans of the homosexual liberation movement. Next, a laminated guide offers a 1980 vocabulary of Mexican gay slang (“Locabulario”) by activist Juan Jacobo Hernández, including a definition of the slur “joto” (faggot): “those beings who dress and move funny: the more visible homosexuals, the ones who refuse – due to tiredness, rebellion or provocation – to renounce their feminine affectations to adopt macho mannerisms.”[11. Juan Jacobo Hernández, “Locabulario”, Nuestro Cuerpo. Lenguaje y Opresión, 2-3, July 1980.] On an opposite wall, the curatorial statement opens with a quote of José Joaquín Blanco’s 1979 important essay about Mexican homosexuality “Eyes I Dare Not Meet in Dreams” (“Ojos que da pánico soñar”): “Shining eyes I dare not meet in dreams because beside them our own would seem blind.”[12. Jose Joaquín Blanco, “Eyes I Dare Not Meet in Dreams [1979],” Trans. Edward A. Lacey. In Gay Roots: Twenty Years of Gay Sunshine, Ed. Winston Leyland, San Francisco: Gay Sunshine Press, 1991, p.291-296.]

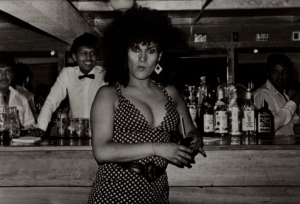

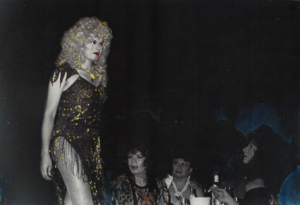

La Paul o La Mantarraya, 1987

from the Night of Queens at the Spartacus

(Noche de reinas en el Spartacus) series

The first Agustín Martínez Castro image on the exhibit, displayed by itself next to the statement, is a 1984 photo titled after Blanco’s essay: Prologue: Eyes I Dare Not Meet in Dreams (Prólogo: Ojos que da pánico soñar). The black-and-white image shows four effeminate young men, two of them in female clothes. We only see three of their faces, whose dark skin and indigenous features don’t fit the ideals of white masculinity privileged by gay culture. They all look to the camera, suggesting different attitudes. Striking a pose and returning the photographer’s gaze was a strategy used by Mexican gay men in early photos linking them to crime. Unlike the defiant poses and looks in those photos, a cautious involvement with the photographer seems to be at play in the Martínez Castro image, suggested not only by the different ways their eyes “dare” to meet him, but also by the gesture of one hand holding another’s right arm. Their “joto looks” are the establishing shot of the exhibit, the frame of reference for queer engagement, looking back, daring to meet, to dream.[13. Curiously, though, during talks at Centro de la Imagen related to the exhibit, many participants mentioned a different Agustín Martínez Castro image as their entry point: a black-and-white photo in which “No” is written over the right side of a bus.]

3. Foundational Irruptions

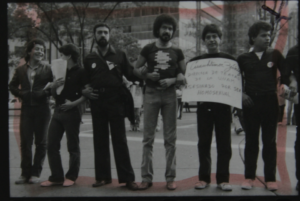

Three pioneering groups of public gay and lesbian activists formed in 1978: the predominantly male FHAR (Homosexual Front of Revolutionary Action), the lesbian Oikabeth[14. Oikabeth is an acronym from the Mayan phrase Ollin iskan katuntat bebeth toth/ Movement of Warrior Women Who Lead the Way and Spread Flowers.] and the mixed gender Lambda Group of Homosexual Liberation. On July 26, 1978, a small group of FHAR members joined a march that honored the start of the Cuban Revolution and demanded the liberation of political prisoners. FHAR’s first public irruption had a surprising connection to Mexican cinema: statements by actor Roberto Cobo (“We shouldn’t confuse homosexual and fag [marica]”), then enjoying the success of his acclaimed performance as the cross-dressing La Manuela in the 1978 film The Place Without Limits (El lugar sin límites, Arturo Ripstein), triggered actions that led to FHAR’s participation in the July 26 march. Newspapers recorded their participation. A few months later, Oikabeth and the Lambda Group joined FHAR in a student-led march that commemorated the 10th anniversary of the Tlatelolco massacre on October 2. Though it wasn’t a gay and lesbian event, this public “outing” is considered the first march of homosexual pride in Mexico City.

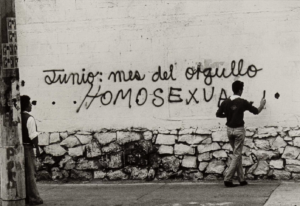

Fernando Esquivel and Juan Jacobo Hernández, June 1979

On June 1979, Agustín Martínez Castro joined FHAR’s co-founders Juan Jacobo Hernández, Fernando Esquivel and Carlos Toimil during their first “markings” (pintas) of public spaces to promote the forthcoming march of homosexual pride, the first one on the last Saturday in June.[15. In light of the exhibit, journalist Antonio Bertrán interviewed Juan Jacobo Hernández about this photo for his weekly column “Nosotros los jotos.” See Antonio Bertrán, “Putos pintando bardas”, Metro (April 24, 2018): p.7.] While other Mexican photographers produced images of the LGBTQ communities in Mexico City, during a recent talk Hernández pointed out the significance of Agustín Martínez Castro as someone who photographed early public gay and lesbian activism “from within.” One of the photos shows Hernández from behind as he finishes writing with black aerosol “June: Month of Homosexual Pride” on a wall. The position of his head and right arm creates the illusion of completing the word with his body, the L that writes the dot on HOMOSEXUAL. The framing also places Fernando Esquivel (on the right) as the one who looks… at the message? the body? the fusion of both?

Paulette and Gerardo Ortega, “La Mema”, June 1980

The photos of the “markings” were among those Agustín Martínez Castro took in collaboration with FHAR, which reproduced his images on their pamphlets. He also photographed the early marches of homosexual pride. Among the activists seen marching is Gerardo Ortega Zurita, “La Mema,” who passed away on June 2018. The slogan “Arriba los putos” (“Up with the putos”) is visible to the left side of his face. World Cup news coverage has brought international attention to the Mexican slur “puto,” critiquing its homophobic use as a pejorative chant during Mexican soccer games. “Puto” is usually translated as gay male prostitute or male sex worker. It’s a Mexican slur rooted in misogyny and the intersection of male homosexuality with female sexual work – and sexual availability. A former sex worker, La Mema became a renowned activist and his home in Ciudad Nezahualcóyotl or “Neza,” on the outskirts of Mexico City, offered refuge to young poor gay men and vestidas (literally “dressed women,” an umbrella term used for transvestite, transsexual and transgender identities).

La Mema played a significant role in English-language scholarship about Latin American sexualities with the 1998 publication of Mema’s House, Mexico City: On Transvestites, Queens and Machos, by sociologist Annick Prieur.[16. The book built on her doctoral dissertation, published in Norwegian in 1994 with a different title. A Spanish edition, La casa de la mema: travestis, locas y machos, was published in 2008.] Though the language now sounds very 1990s, Prieur’s study offered a welcome point of view that differed from earlier sociological studies and her nuanced analyses contested prevalent notions about Mexican male homosexuality, especially in relation to effeminacy and poverty. Annick Prieur described La Mema, nearing 50 when they met (Prieur says mid 30s) as: “not the most beautiful… but he is a good dancer and a skilled seducer of handsome young men.”[17. Annick Prieur, Mema’s House, Mexico City. On Transvestites, Queens, and Machos, University of Chicago Press, 1998, p.7.] In the Mexican gay magazine Del otro lado (From the Other Side), a February 1994 caption described La Mema, then in his mid 50s, as “Torcida, aunque gordita” (Bent, though chubby). Shortly before his death, journalist Antonio Bertrán published an interview in which he called the 79-year-old Mema “Una jotita muy cabrona” (more or less: “A very badass little fag”).[18. Antonio Bertrán, “Una jotita muy cabrona”, Metro (June 19, 2018): 6.] The three scenarios fondly celebrate La Mema for defying the expectations attached to his background and image.

4. Queers of the Night

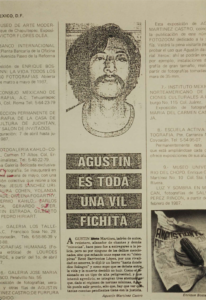

Agustín Is a Vile Little Scoundrel (Agustín es una vil fichita), 1985

from the File 13 (Expediente 13) series

During Agustín Martínez Castro’s lifetime, the sensationalist language and imagery of Mexican tabloids maintained the tradition of giving visibility to LGBTQ Mexicans, especially “effeminates” and “transvestites,” by linking them to exploitation, criminality and “low culture” (double entendre, gossip, “popular” humor, cabarets, brothels, photo novels, etc.).[19. Some of Alarma!’s images of “vestidas” were reproduced in the 2014 photo book Mujercitos!, with introductory texts by scholars Cuauhtémoc Medina and Susana Vargas Cervantes.] Martínez Castro’s File 13 series (1985) is a mode of queer engagement with tabloid images in which the artist appropriates, makes fun and rewrites the tabloids. The original Spanish title of Agustín Is a Vile Little Scoundrel, for example, plays with the meanings of the word “ficha,” used in the diminutive, as scoundrel, token or file. This mode of self-portrait also mocks artistic self-representations. On the lower left side, there is a description of Agustín Martínez Castro’s exhibition of “photographies, xerographies and other –phies” (like “jotographies,” a term the artist used). This self-portrait contrasts with an undated photo of the artist, by Gilberto Chen, shown at the exhibit. Martínez Castro – wearing short hair, sunglasses, mustache, T-shirt and jeans, and exhaling smoke with cigarette in hand – strikes a pose that brings to mind the images of San Francisco white gay masculinity in Hal Fischer’s landmark Gay Semiotics (1977). Both show a playful attitude towards masculine prototypes, which Agustín Martínez Castro also engaged with in My Playgirl Got Wet, a series which intervened images of naked male bodies that, though marketed to straight women, were also consumed by gay men.

La Creel, 1987.

from the Marquee. Homage to Tito Vasconcelos

(Marquesina. Homenaje a Tito Vasconcelos) series

The connection between documentation, “pirated image” and drag aesthetics in Agustín Martínez Castro’s work is evident in the series Marquee. Homage to Tito Vasconcelos. In “La Creel” (1987), for example, Tito Vasconcelos appears as Catalina Creel, the evil eye patch-wearing matriarch from the Mexican soap opera Cradle of Wolves (Cuna de lobos, 1986 – 87), a character rooted in the gay male imagination[20. The story goes that watching the 1968 black comedy The Anniversary sparked the imagination of gay playwright Carlos Olmos. Bette Davis stars as a domineering one-eyed matriarch with color-coordinated eye patches whose middle son shot out her eye with an air gun. Catalina Creel became so popular that cultural critic Carlos Monsiváis – adding another gay dimension to the character – wrote a 1987 column titled: “Catalina Creel for President.”] and the notion of femininity as drag, whose murderous diva presence added touches of camp and dark humor to an otherwise conventional maternal melodrama.

A well-known gay artist and activist, Tito Vasconcelos starred in two trailblazing moments in the history of Mexico City “gay theater” also featured in Martínez Castro’s Marquee series. In 1980, Vasconcelos appeared in And Yet, They Move (Y sin embargo, se mueven), a show in which the four gay male cast members “came out” on stage and whose poster art also appropriated tabloid style.[21. Conceived by composer José Antonio Alcaraz (1938 – 2001), the show was presented under the auspices of the theater department at the National Autonomous University of Mexico.] In 1984, Vasconcelos starred in Butterflies and Fag-Things (Mariposas y maricosas, I’m borrowing Antonio Prieto’s translation.[22. For an analysis of the show, see Antonio Prieto, “Camp, carpa and cross-dressing in the theater of Tito Vasconcelos,” Corpus Delecti: Performance Art of the Americas, Edited by Coco Fusco, London and New York: Routledge, 2000, pp. 83-96.]), which included his famous characterization as Hollywood diva Joan Crawford and a politicized reinterpretation of Mexican TV cook Chepina Peralta. The performances of Vasconcelos complicated and subverted the notion of being “vestida” through characters with layers of drag and queer associations: Hamlet as rock star by way of Sarah Bernhardt in And Yet, They Move, or Joan Crawford rehearsing different female roles by way of Mommie Dearest in Butterflies and Fag-Things. In his Marquee series, Agustín Martínez Castro’s intervention of the Tito Vasconcelos’s images added another layer of drag or queer engagement.

Parade of Winners (Desfile de triunfadoras) (Charo), 1988

from the Night of Queens at the Spartacus (Noche de reinas en el Spartacus) series

Agustín Martínez Castro also “pirated” – to borrow the curatorial term – the images in his series Night of Queens at the Spartacus. Inaugurated in 1984 by Jorge Cruz Garfias, Spartacus is a notorious gay nightclub located in Neza, an area of ill-repute for being poor and dangerous. From the start, Spartacus featured entertainment with drag queens and go-go boys, and its clientele included vestidas and sex workers. The drag shows, dancers and dark room became legendary, attracting customers from the city and even celebrities (like Spanish pop star Alaska). Besides taking photos, Agustín Martínez Castro used the disco club as exhibition place. In 1988, Martínez Castro showed From 10 to 11 p.m. (De 10 a 11 p.m.), a series about the backstage transformations at the Spartacus, thus bringing the images back to where their creation began.

5. Names of the Game

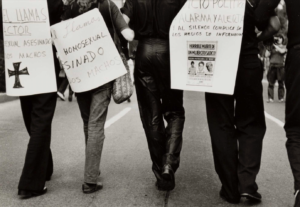

both Untitled, June 1984

In “The Look of Gay Liberation,” Steven F. Dansky notes that: “Paradoxically, most subjects of the early photographs of Gay Liberation, while out enough to be photographed, were not named in any caption and are thus anonymous.”[23.Steven F. Dansky, “The Look of Gay Liberation,” The Gay & Lesbian Review Worldwide, 16.2 (March/April 2009): 28.] The untitled Martínez Castro photos taken during the marches of homosexual pride also makes the activists anonymous, whether seen from the front or behind. During the 1984 march, activists that year carried signs to denounce homophobic murders. While the subjects of the photos can be identified by those who knew them, anonymity adds power to the political act in the image, as the bodies standing with arms intertwined become collective identities for the names on the signs. The left photo names Spanish actor Rafael Llamas, found dead in his apartment in 1980. The right one names Cuauhtémoc Zúñiga, head of the theater department at the National Autonomous University of Mexico, murdered in his apartment in 1982, at age 36. This march is considered a turning point in early public gay and lesbian activism in Mexico City. In 1984 clashes between activist groups weakened the notion of collective identity in the movement of homosexual liberation, starting a period of fragmentation that historians extend to the late 1990s.

Agustín Martínez Castro wrote a brief text about the reduced participation and growing divisions among activist groups in the 1984 march. He compared it with the June 1980 march, when the public protest against sexist oppression seemed a growing movement.[24. Agustín Martínez Castro, “Eutanasia para el movimiento gay”, La regla rota, Num. 2 (Summer 1984). The title, “Euthanasia for the Gay Movement,” draws from a notorious pamphlet (Eutanasia al movimiento lilo /Euthanasia to the Lilac Movement) distributed during the 1984 march by the Colectivo Sol (Sun Collective), a group created in 1981 after the dissolution of FHAR.] This weakening of the movement took place around the time the first cases of AIDS were reported. In 1987, Martínez Castro published a much longer text dedicated to the virus: “Psychosis – Irresponsibility – Disinformation – Sensationalism. The Other Face of the Disease.”[25. Agustín Martínez Castro, “Sicosis – Irresponsabilidad – Desinformacióón – Amarillismo. La otra cara de la enfermedad”, La regla rota, Num. 4 (1987).] (In Spanish, the first part of the title forms the acronym SIDA [AIDS].) Starting with the sentence “The problem is serious,” the article reports the different ideas circulating about the virus and denounces poor public health treatments and sensationalist media coverage.

Two parts stood out for me. On the second section, Agustín Martínez Castro names two patients – first name only – whose fates were affected by prejudice. Toño, to whom the article is dedicated, was a doctor who erroneously received treatment for leukemia. His colleagues didn’t know about his sexual orientation and didn’t think he could have a “faggot’s disease” (“enfermedad de putos”). Ricardo, on the other, committed suicide after being mistreated as an AIDS patient, though he was likely misdiagnosed solely for being homosexual. Towards the end of the article, the tone of the article shifts with a humorously ironic “Questionnaire to alleviate paranoia and lift the spirit” (Cuestionario para atenuar la paranoia y elevar el espiritu)” that places the AIDS virus in the broader context of other social struggles. Published the year before Martínez Castro tested positive, the article is especially interesting given the small number of explicitly AIDS-related artwork at the retrospective, which ends precisely on the year of his diagnosis.

from the Memorial Quilt series, June 1988

In 1988, while in New York City, Agustín Martínez Castro photographed the touring AIDS Memorial Quilt and tested positive to HIV. The fatefulness of that trip to New York gives added poignancy to his photos of the quilt. They are tight shots that reframe the panels and privilege certain details, creating a feeling of intimacy. At times, Martínez Castro’s images eliminate the names and dates in the panels to strong effect. His photo of lovers Paul Fitzsimmons and David Aurand, unidentified by Martínez Castro, favors Paul’s loving look over David. Erasing the names and dates makes them anonymous, but it also offers a more intimate look at the couple than when the full panels are seen side by side. Their heads are shown in half, looking in different directions, in panels of different colors, increasing the sense of loss and separation caused by the disease.

6. Blue Prelude

from The Lips of The Hole (Los labios de El Hoyo) series, 1987

Blue has got hope in it, always.

– Derek Jarman, 1993[26. Quoted in Ken Shulman, “When Creation Fills a Deathly Silence: Derek Jarman Finds Hope in ‘Blue’”, New York Times (October 3, 1993): 25.]

Pirates on the Boulevard ended with an attention-grabbing sign of pleasure (goce): red neon lips, a contemporary recreation of a 1987 sculpture titled Of Burning Purple (De púrpura encendido). On the opposite wall, a photo showed two men mooning the camera with their hairy asses, creating the effect that the neon lips kissed them. This last section of the exhibit paired two series of images about Agustín Martínez Castro’s affective complicities with friends and lovers. The photos in The Lips of The Hole (1987) series were taken at a property in the Colonia Roma district that was partially ruined by the 1985 Mexico City earthquake. Agustín Martínez Castro and other artist friends and lovers appropriated the space to use it as a clandestine lair for artistic and sexual experimentation, exhibition and performance.[27. The Lips of The Hole series includes explicit images not shown in the exhibit. During a tour, the curator explained his decision to exclude them. In addition to pointing out the limitations of space, he proposed, “I think there are images better left unseen, anonymous. There are other images that one can imagine, that could be interesting as evocations, not as visible.” César González Aguirre , Guided Tour of Pirates on the Boulevard, Centro de la Imagen, Mexico City, May 18, 2018.]

The hallway at the museum led visitors to end their tour of Agustín Martínez Castro’s work with a neon red kiss, but I would like to read against the grain and end my brief looks with shades of blue. In 1982, Martínez Castro collaborated with friend María Eugenia Chellet to make a series of slides in which they playfully intervened with the visual imaginary of heterosexual desire created in relation to the popular songs of Mexican composer Agustín Lara.[28. In 1984, Agustín Martínez Castro edited a photo book also titled Blue: “a free (and arbitrary) evocation of nostalgia at the wrong time.”] Blue (Azul) is titled after an early 1930s Lara song indelibly associated to the composer’s image as bohemian dandy and lover of women. It has a melancholy melody, accompanied by some very Lara-esque imagery: “blue, like the bag under a woman’s eye, like a blue ribbon, blue of morning” (azul, como una ojera de mujer, como un listón azul, azul de amanecer), that immediately puts the listener in nostalgic mood.[29. “Azul” was memorably used in the 1991 María Novaro film Danzón, which also engages with the romanticism of 1930s & 40s Mexican popular music. The song plays, first as instrumental and then sung by Carmen Salinas, during a post-coital scene in which the heroine (María Rojo) lights up a cigarette in bed while her much younger sailor lover sleeps next to her.] During a recent event at Centro de la Imagen, María Eugenia Chellet presented the slide show and later warned against the misperception of Agustín Lara’s romantic songs as kitsch. She noted the sincerity of feeling attached to his compositions and the Blue collaboration. I will add that its imagery – which many would find dated and laughable – is as valid a sign of queer pleasure and sexuality as the neon red lips, in which the dagger-like eyes of divas like María Felix could be daring us to indulge in the queerest of dreams.

from the Blue (Azul) series, 1982

by Agustin Martinez Castro and María Eugenia Chellet