Belén Vidal on the 18th MÁLAGA SPANISH FILM FESTIVAL

Mediático is very happy to present another, excellent, film festival report by Belén Vidal, Senior Lecturer in Film Studies at King’s College, London. Vidal is author of Figuring the Past: Period Film and the Mannerist Aesthetic (Amsterdam University Press, 2012) and Heritage Film: Nation, Genre and Representation (Wallflower Press/Columbia University Press, 2012), and co-editor of The Biopic in Contemporary Film Culture (with Tom Brown, Routledge, 2014) and Cinema at the Periphery (with Dina Iordanova and David Martin-Jones, Wayne State University Press, 2010).

On 18 FESTIVAL DE MALAGA CINE ESPAÑOL / 18th MÁLAGA SPANISH FILM FESTIVAL (17-26 APRIL 2015)

By Belén Vidal

In an era of global viewing and cosmopolitan festivals, the Málaga Spanish Film Festival or, the Festival de Málaga de Cine Español (FMCE) stubbornly wears its local flavour and national stripes with pride. This ten-day festival offers a showcase for Spain-based production principally addressed to the mainstream exhibition circuit and a cosy red-carpet experience cut to the measure of its local stars. The majority of the fifteen films in the official selection are already slated for domestic release throughout the late spring and summer. In the absence of an attached market, the FMCE lacks real impact in the industry calendar other than in terms of promotion of forthcoming releases. Nevertheless, this eminently popular festival enhances the cultural profile of one of the most visited tourist destinations in Southern Spain (Málaga advertises itself as the birthplace of Pablo Picasso, and hosts a pop-up Pompidou Centre since 2015). I landed in Málaga ready to get a first-hand taste of popular cinephilia.

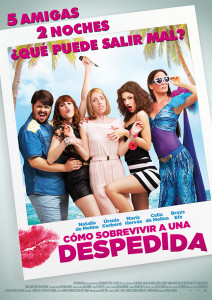

The festival feels laidback and easy-going, with most of its two hundred screenings running in five local cinemas at the very centre of this small cathedral town with an extensive pedestrianised core. The FMCE’s audience is made up of a mixture of Spanish journalists and film professionals, a small contingent of foreign visitors and an enthusiastic local population, with festival crowds spilling over to the local tascas and restaurants on the port area. As I did not attend the evening plush red-carpet premières I was spared the turmoil caused by teenage fans headhunting for selfies with the stars (although some of the most eager among them could be spotted on blankets and sleeping bags outside the Cervantes Film Theatre at the 9am press screenings). The presence of these occasionally riotous female teens (infamously nicknamed “chonis” [LINK]) and their aggressive chasing after celebrities have become part of Málaga’s identity. Their picture graces the banner of the FMCE website [LINK] and they are the primary target audience of some of the popular hits that have premiered at the festival over the years, such as the 2009 comedy Fuga de cerebros/Brain Drain (which later spawned a sequel). The robust success of this American Pie-style film is an example what Paul Julian Smith has appropriately called “the Mario Casas effect” after one of the male stars who best embodies the dependence of the film industry on home-grown television stardom. As Smith has claimed, this growing convergence between media through shared narrative formulas and cross-over creative talent is reanimating the connection between Spanish cinema and its domestic audience.[i] To say there is a new-found love at work may be too bold an assumption, but Málaga certainly works hard at promoting the star factor of this youth-oriented cinema.This synergy is partly the product of the changing mediascape in which Spanish cinema is embedded. To a certain extent, Málaga panders to a corporate idea of Spanish cinema as pre-packaged content that fits in with the television channels’ brand image alongside their in-house production of sitcoms, soaps, drama and celebrity shows. Indeed, films backed by the powerful media groups Canal + and Antena 3/Atresmedia (which is also one of the festival’s current sponsors) have become ubiquitous in the festival’s programme—films such as this year’s closing gala Sólo química (Just Chemistry) by Alfonso Albacete, which appropriately plays on a young woman’s fascination with celebrity culture. Another example is Manuela Moreno’s Cómo sobrevivir a una despedida (How to Survive a Hen Weekend), a Bridesmaids-style female friendship comedy of errors headed by Natalia de Molina (recent winner of a Goya for Best New Actress) about a group of “girlfriends” (including their gay male best friend) who whisk the prototypical good girl in their group off to a madcap hen weekend in the Canary Islands. Underpinned by garish visuals, a “be yourself” aspirational narrative, and a retro-touch of 1990s grrl power (complete with a Spice Girls impersonation number given seal of approval by the presence of Emma “Baby Spice” Bunton in a cameo role as an X-Factor style jury member) the film is telling of the way private television channels (Antena 3 in this case) envision cinema as a further platform through which to reach cross-generational audiences.

If there’s a strand of production that Málaga has become associated with it’s the social film and the middlebrow drama—usually medium-budget films that join quality (focus on characters, a strong sense of locale) and accessibility (touching on sensitive themes in a non-confrontational manner). Unlike the genre hybrids discussed above, these films look and sound recognisably “Spanish”. Although films that document social reality have lost ground to the ever-growing budgets and overwhelming media presence of genre films, the times are ripe for new fictions that reflect on the experience of living in austerity Spain. I couldn’t catch Techo y comida (Bed and Board) by first-time director Juan Miguel del Castillo; this film about the human crisis caused by evictions was recognised with the prize for best actress to the ubiquitous Natalia de Molina, who plays an unemployed single parent facing the loss of her lodgings. However, it was the festival’s opener, Hablar (To Talk, directed by veteran Joaquín Oristrell) that stood out as this year’s state-of-the-nation film, but also as a rejoinder to the stylistic predictability of social cinema. Set on and around Lavapiés Square (a Madrid landmark, and the centre of a low-rent neighbourhood with a diverse migrant population) Hablar is made of an 80-minute single take. The continuous shot captures discrete stories strung together by the hand-held camera’s fluid movement around the square in a hot August night. In the spirit of street theatre, each scene is an open-ended micro-play for one or two actors. The film originated in a series of acting workshops conducted by Oristrell and respected drama coach Cristina Rota between 2009 and 2011, but Hablar draws its emotional punch from the pressure arising from both dramatic content and cinematic form. The camera follows characters often in motion, who chat away incessantly, constructing self-protective fictions or exposing their private selves in the public space of the square. The urgency of the crises they give voice to (arising from loneliness, insecurity, addiction, long-term unemployment, exploitative employment, paranoia and or even sheer hunger) is highlighted by the relentlessness of the night shoot on a logistically tough location. The space of fiction created by the professional actors and the presence of the camera is palpably carved out of the noise-filled setting and its contingent human elements. Like another recent mosaic-like national allegory—Gente en sitios (People in Places, Juan Cavestany 2013)—this is an unpolished, necessarily uneven film yet there’s a superbly enjoyable element of unpredictability to it. The street interactions yield some brilliant comedy moments as well as charged drama, which rub off the roughness at the edges. Embracing the theatricality of its premise, Hablar grafts into the textures of urban naturalism elements as disparate as rambling monologues about surveillance conspiracies, an argument over street posters of Podemos (perhaps the first explicit mention to the rising left-wing party in a Spanish fiction film) and even a bite-sized musical number that is a true showstopper: Antonio de la Torre’s star appearance performing five minutes of a kind of flamenco-rap (freely based on a comic song by Pepe da Rosa) about the anxiety provoked by everyday queuing in banks. Both experimental and truly popular, Hablar has been described as “Spain in a long take” [LINK] and its elevation of Lavapiés into a microcosm of the social ills affecting the nation is not exactly subtle. However, what this perambulating, talkative movie best captures may not be a fully-formed portrait, but a healthy desire for collective self-representation as a form of resistance.

The official selection also included a number of co-productions with an explicit fit between financial arrangements and transnational themes at the level of setting and story. The global-debt thriller La Deuda/Oliver’s Deal, by Lima-based director Barney Elliott was, for me, the most interesting of them, even if as a piece of cinema it falls short of its political ambitions. The film focuses on the profit-seeking operations of American hedge fund bankers speculating with the historical debt contracted by the Peruvian government with landowners, and their impact on the lives of individuals. Peruvian mountain farmer Florentino (an impressive Amiel Cayo) tries to retain the land that provides a livelihood for him and his family; María (played by Elsa Olivero, who won the prize for best supporting actress for her tense performance) is a Lima nurse struggling with the consequences of the cuts to basic services implemented by the government as a result of the pressure exerted by the banks. A great deal of story time however focuses on ambitious broker Oliver (Stephen Dorff) and, secondarily, on his best friend Ricardo (Alberto Ammann, looking not entirely plausible in the part of a high-flying New York broker of humble Peruvian origins). Therefore the otherwise compelling three-stranded narrative ends up focusing on the first-world white male protagonist’s journey, and his eventual awakening to the reality of shattered lives caused by the extortionate practices he upholds. Nevertheless, this Peru/Spain/USA co-production finds a good balance between production context, local knowledge (the film is shot in English, Spanish and Quechua, which gives it an extra dose of authenticity) and an absorbing, if compromised, thriller narrative. La Deuda feels somewhat derivative from the more ambitious Babel (Alejandro González Iñárritu, 2006) but this is nevertheless a well-made genre film with its political heart firmly in the right place.

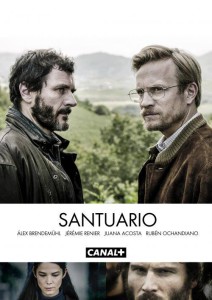

Much less successful is Gerardo Herrero’s production Tiempo Sin Aire (Time without Air, dir. Andrés Luque and Samuel Martín Mateos) in which María, a Colombian nurse (Juana Acosta), moves to Santa Cruz de Tenerife with her heavily traumatised son in search of the Spanish mercenary soldier who took part in the gang rape and killing of her eldest daughter. The film uneasily navigates between flashbacks of the atrocities and the rather unconvincing love story between the protagonist and the school psychologist (played by veteran Carmelo Gómez) who takes an interest in her son. The film ends up relegating the Colombian guerrilla wars to mere backdrop for a rape-revenge melodrama. Screened out of competition, the Canal + television movie Le Sanctuaire (Sanctuary) by Olivier Masset-Depasse offers a stronger take on another history of violence. Le sanctuaire focuses on the political impasse that the presence of ETA members on French soil posited for the Mitterrand government in the early 1980s. French authorities were confronted with the decision either to hand them over to the Spanish authorities at a time in which there were reasonable doubts over the fairness of the Spanish judicial system, or to retain the right to give political asylum—to offer sanctuary—to members of the Basque group responsible for armed actions. ETA’s history has been told in film and television from a variety of angles, yet this gripping docudrama brings a refreshing transnational vision on the conflict, if one that is clearly geared to French audiences and reliant on the face-off between men as agents of history (superbly played by Jérémie Renier and Àlex Brendemühl, on opposite sides of the negotiating table).

On a very different register, another fascinating film with a transnational vision was Pablo Martínez Pessi’s Tus padres volverán (Your Parents Will Return), a documentary that interviews the daughters and sons of Uruguayan political exiles living all over Western Europe, and teases out their experiences as individuals divided between their land of origin and their adoptive countries, between the past and the present, and between being children and being parents. This is a film that gains affective traction as it goes on and digs deep into the emotional traps set up by national identity, exile and belonging.

Romantic comedy Sexo fácil, películas tristes (Easy Sex, Sad Movies) by Alejo Flah explores a different and rather lighter side of transnational filmmaking. Pablo, an Argentinian one-hit novelist living in Buenos Aires (Ernesto Alterio) is struggling to complete a commissioned script for a romantic comedy set in Madrid at the request of a producer friend embarked on a transnational film business venture. So the film works on two fictional levels: on the one hand, we get the film Pablo is writing, a textbook romcom played by the impossibly perfect-looking romcom couple Quim Gutiérrez and Marta Etura, complete with clichéd single best friend (embodied by Carlos Areces, whose superb comic talent merited more screen time). The couple goes through the motions (boy finds girl, boy loses girl, boy recovers girl) in an impossibly perfect-looking Madrid (including the briefest of detours via Paris, so both the-film-within-the-film and, one suspects, the film we’re watching, can satisfy co-production requirements imposed by the minority French partner). On the other hand, this basic plot comes wrapped up in the emotional ups-and-downs and rather more prosaic life of the romcom’s creator. As the mildly depressed forty-something writer, Alterio adds a layer of depth to this light concoction (his nuanced performance was rewarded with the best actor prize). Behind the unpromising title lays a thin but winsome film that wears its meta-narrative on its sleeve, holding a mirror up to the simple formulas and intricate geographies of contemporary romantic comedy.

Trailer Sexo fácil, películas tristes

I hardly had the chance to dip into the more heterogeneous and experimental Zonazine sidebar, nor in the Documentary and Latin American Territory sections. Alongside a rich programme of parallel events (lectures, masterclasses, round tables and workshops) they give a sense of the expanding remit of the festival. However, as a space for popular cinephilia, one needs to look at the way that Málaga has been instrumental not only in promoting stars but in launching the careers of popular auteurs such as Daniel Sánchez Arévalo or the versatile Paco León, who was in town to receive the Eloy de la Iglesia special award. León, whose two films Carmina o revienta and Carmina y amén [LINK 4] reaped awards at the festival in 2012 and 2014 respectively, was known to audiences for his television roles before moving on into film directing. His “Carmina” diptych is both an experiment in mixing televisual and film genres, an innovative production venture (Carmina o revienta was launched on a simultaneous multi-platform release) and a curious family affair: the two films feature the director’s equally well-known sister, rising actor María León, and turned Carmina Barrios, mother to the León siblings, into a charismatic screen celebrity. This year, the official competition provided ample room to other actors turning in their first feature film, including Leticia Dolera’s quirky romcom Requisitos para ser una persona normal (Requirements to be a normal person); actor and short filmmaker Zoe Berriatúa’s debut feature Los héroes del mal (Heroes of Evil), a violent high school drama with a trio of vigorous performances, and especially Daniel Guzmán’s heartfelt autobiographical film A cambio de nada (Nothing in Return), which carried off the top prize—the Golden Biznaga.

The highlight of my four days in Málaga was the special screening of a lost film by one of the most celebrated actor-directors in the history of Spanish cinema. Fernando Fernán Gómez nearly went bankrupt by single-handedly adapting, producing, directing and performing in El mundo sigue (Life Goes On, shot in 1963). El mundo sigue is nothing short of a film maudit: it did not have a proper release at the time due to problems with the censor (although, unbeknownst to its director, the film was briefly screened in Bilbao) and has been rarely seen since. A relentlessly bleak melodrama, the film focuses on the contrasting fortunes of two sisters from a working-class family. “Good girl” and former beauty queen Eloísa (Lina Canalejas) is trapped in a circle of humiliation and destitution caused by her dependence on her good-for-nothing gambler of a husband, Faustino (played with absolute lack of vanity by Fernán Gómez). “Bad girl” Luisita (Gemma Cuervo) waives respectability but achieves security and self-confidence through her relationships with wealthy men. Partially shot on location and capturing a vivid snapshot of life in Madrid, El mundo sigue casts a scathing look on family relationships and the double standards that constrained women’s lives at a time in which modern lifestyles started to free them of their traditional roles as housewives and mothers. The film is so unsparing in its social critique that it is little wonder that the Francoist censors clamped down on it. Seen today, El mundo sigue is fascinating for its awkward mixture of emphatic, over-the-top melodrama and its bold use of formal devices such as diegetic voiceovers, quick zooms and montage to insert a radical disjunction between the characters’ desires and aspirations and the reality of their lives.

[IMAGE 8] El mundo sigue: screening and round table at the auditorium of the Picasso Museum in Málaga.

[ii] Orson Welles’s 1965 Spanish production Falstaff. Chimes at Midnight also received a special screening at the festival.