Queer Uncanny#1: Mulholland Drive “Have you done this Before?”

The lesbian relationship is central to Mulholland Drive (Lynch, 2001) and this relationship – fractured, repeated and disturbed – presents an uncanny figuration of queerness.

The two main characters in David Lynch’s Mulholland Drive, Betty/Diane and Rita/Camilla, perform their relationship in two opposing ways during the course of the film. During the first part, Betty, an aspiring movie star, comes to stay in her Aunt Ruth’s apartment in Hollywood where she encounters Rita. Rita is amnesiac, hiding desperately in the apartment in order to escape some terrible, possibly fatal, trouble following a car crash on Mulholland Drive. Betty is a naïve, sparky blonde fresh from the little town of Deep River, Ontario. Rita is a voluptuous femme fatale in both physical and psychic danger. Her bewildered beauty and languorous stage presence give a false impression of depth. Rita allows herself to be guided by Betty in her project to work out her ‘true’ identity and they eventually become erotically involved.

Doubling is used to effect lesbian desire. The two women often resemble each other or other characters. The sense of the real being occluded by the fantasied is apparent in the repetition of the lesbian relationship in two different ways. Identification is deeply eroticized, and the location of an identity, any identity, seems to become sexually charged for the two main characters.

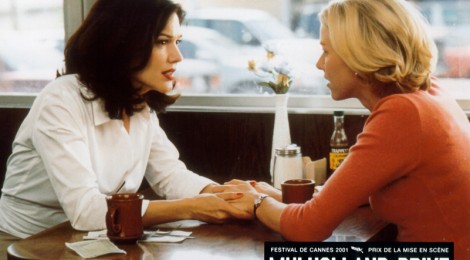

When Betty breathily asks Rita “Have you done this before?” as they begin kissing, she helps the viewer to understand how lesbian identity is constructed in the film. Though the question could just as easily refer to any type of sexual activity, it is implied that it concerns lesbianism specifically. Rita’s answer “I don’t know.” is at once sincere and stylized. The character draws attention to the fact that she is a cipher, her identity being put together as she goes along. It just so happens that in the first part of the film she is figured as exclusively lesbian, but she has no idea if this is typical behaviour for her.

We never see how this romance plays out because halfway through the film Naomi Watts and Laura Elena Harring vanish, only to reappear in a sadomasochistic love triangle. The beautiful and successful Harring (now Camilla) leaves Watts (now Diane) for the movie director Adam Kesher, humiliating her deeply in the process. The penultimate scene shows Diane putting a gun in her mouth, unable to live with the longing she has for the murdered Camilla, and the guilt she feels for hiring her killer.

This is troubling in that the second half of the story relies on the viewer’s preconceptions of the tragic lesbian in order to function. We see Diane as bereft, incapable of dealing with Camilla’s defection to a man. This kind of ‘straightening’ behaviour fulfils the viewer’s expectations that the woman who is solely lesbian is someone to be pitied and ignored, whilst the bisexual woman is to be congratulated for returning to heterosexuality. Where we see the violent suicide of Diane and her rotting corpse, in the last image we have of Camilla she is laughing, radiant and apparently sexually fulfilled. She is not presented as a figure to provoke our disgust or scorn.

Diane does not seem to choose her path of murder and suicide because of defiance and bravery, but rather because of a fixed nature that cannot be ‘cured’ through humiliation or fear. This fatal sameness, or inability to move fluidly between identities, is seen as her central flaw.Diane is not allowed happiness because of her inability to ‘straighten’her orientation. If we compare this ‘sameness’ of Diane’s in the second half of the film as the ugly truth, and the first half as her masturbatory fantasy or dream, as many critics have, then this raises another interesting point. Diane appears unable to change and cannot gain control over the course of events necessitating her descent into violence. The closed logic of Diane’s world is not read as noble, but rather as a byproduct of her inability to change. Her ‘sameness’ is escapable only through violent death.

Another way in which sameness functions as the locus of lesbian desire is in the use of stock characters and clichés. In the first half, Betty represents the stereotype of the naïve schoolgirl, experimenting coyly as though at a sleepover. Rita is the femme fatale, her voluptuous body, forties make-up and name taken from a Rita Hayworth poster become almost over-determined in their representation of a sultry, noirish beauty. There is something unsettling and uncanny in their sexual relationship. heathr K. love, in her work * says: Both the schoolgirl and the femme fatale are stock lesbian characters, but they are not supposed to end up in bed together. Betty’s opening invitation to have Rita join her in the bed recalls a tradition of boarding school romances that walk a fine line between innocence and experience, between cuddling and depravityThe uncanniness operates because the characters look like real people but they have no psychological depth. At one and the same time they are individuals, they are actors and they are symbols. Even as they perform the lesbian relationship, it does not make sense as it feels as though the stereotypes should not be in the same story in this way. It is only if we reject psychological truth and allow the dream-like illusory quality of the film to become foregrounded that these reductive, flimsy portraits work.

Sameness, in the sense which Sara Ahmed uses it in her study * refers to a kind of homophobic preconception in which “the very idea of women desiring women because of “sameness” relies on a fantasy that women are “the same”. This betrays a kind of social and sexual arrogance, as though women who choose each other are not capable of the kind of challenging diversity to be experienced in a heterosexual relationship. It also assumes that there are more differences between men and women than there are between two women or two men.

As ahe other guests at Camilla’s engagement party and she seems to undergo a kind of breakdown. As Ahmed says “This association between homosexuality and sameness is crucial to the pathologizing of homosexuality as a perversion that leads the body astray.” Diane is subject to this pathologizing and her already weakened personality becomes reduced further. She becomes a conduit for vengeful desire, a sick lust which drives her to literally unspeakable acts. The murder is neither witnessed nor discussed other than obliquely. And in this way, Diane also becomes a witch-like figure, a spiteful yet numinous creature who resides outside of ordinary society.

The film resists any single interpretation. Just as there is no ‘true’ reading of the story, so there is no single location for lesbian desire. The process of doubling the events of the film, showing them twice from different angles, allows different types of lesbian desire to co-exist. Rather than positively presenting a multiplicity of lesbianisms, the characters are inescapably intertwined, the actions of one fatally affects the other. It is as though the lesbian desire continues to dwell in the site where the two women double, even as it dissipates on the surface, subject to the withering male gaze. If Diane is a sadist, then so is her double Camilla who humiliates her lover past all endurance and forces her to take drastic action.

Diane becomes a vicarious murderer. She receives a key to show that the murder has been committed: an all-too-obvious Freudian phallic symbol cannot surely be an accident. It is this murder which drives Diane to her remorseful suicide and it was Freud who wrote that “’If what subjects long for most intensely in their phantasies is presented to them in reality, they none the less flee from it’”. Zizek believes that his “point is not merely that this occurs because of censorship, but, rather, because the core of our fantasy is unbearable to us.” When she looks at the key and sees that her wishes have been fulfilled she can no longer bear it and goes to her death screaming

It is interesting to think of the lesbian desire as almost a by-product of the search for identity and the ‘voraciousness’ of the two characters. The girls are clear opposites – dark, smouldering, enigmatic Rita is a perfect fit with blonde, clear-eyed, optimistic Betty. By giving them a sexual relationship, it is almost as though they have been placed on top of each other, the negative tinted with colour, to create the whole picture.

This reading is one that has been applied to the cinematic representation of the love between Rita and Betty. However I would disagree with this kind of reading. I saw the scene as cold and a little cheap. It maintained lesbian stereotypes and was intentionally titillating in the process. Laura Elena Harring says of Lynch’s direction of the love scene that “it was kind of cute,” and “one time he went, ‘Don’t be afraid to touch each other’s breasts now.’ “In technical terms it seems hard to distinguish this artistic direction from a pornographic scene. We watch two parts of a puzzle come together and the pleasure is intellectual, not sensual or empathetic.

Diane subjects herself to a sadomasochistic compulsion to repeat all that has happened to her in a way that is reminiscent of post-traumatic stress disorder. With Diane, sex is bound intrinsically to death and in her character there is the alignment of eroticism with death-drive. Diane at this stage seems to want to change her identity, to sublimate her guilt into a fantasy which threatens to break down several times. Diane repeats the events until they become more palatable and creates a situation where the lesbian desire is recast as mutual, even initiated by Rita/Camilla.

A more unsettling repetition in the film is that of Diane’s death. First we see her rotting body curled foetally on a bed in a locked apartment. Rita and Betty break in and travel through the darkness and the stench to uncover her horrific corpse. Like the ‘unbearable core of our phantasies’ described by Freud, this invasion of ‘the real’ into the languid dreamscape of the first part of the film is terrifying to look upon. Love sees it as a natural side effect of homophobia. She says that:

As long as lesbianism is socially denigrated, her corpse will continue to turn up in the midst of even the dreamiest lesbian fantasy. Diane Selwyn is a structural effect of homophobia, one of the tragic others that modernity produces with such alarming regularity.

We later see Diane run into the same bedroom and shoot herself in the mouth to end her terrible suffering. This could be seen as an extreme kind of escape from the overwhelming nature of the dream she is forced to inhabit now that she is cursed with the relentless compulsion to repeat. Diane’s death is witnessed twice but Camilla’s death is obscure, offstage. However, the impact of Camilla’s death is felt over and over again. But, even in Diane’s fantasy her body is not discovered for weeks, no one cares about her. Once we know what has happened later then Betty’s sudden disappearance in the first half of the film, leaving Rita alone in a strange world, begins to look like a version of her death. Later, during the discussion with the hitman, the blue key which signifies the death has taken place and Diane’s neighbour telling her ‘those two detectives came by looking for you again’, are all ways of repeating the impact of Camilla’s death.

With all of these deaths there also come hauntings. The intrusion of rotting corpses and filthy, deformed characters punctures the dreamy beauty of Mulholland Drive. In fact, Diane’s decomposing body is all the more shocking for being discovered by two figures who belong in a far less gritty story. Ekeberg says that “guised as an unsolvable riddle, Mulholland Drive contains no comforting answers about reality.” David Lynch himself has refused to make clear his intentions or sympathies and instead says: “‘a film is its own language, an entity. It should not be translated back into words.’” There is an unsettling, haunting quality to the film with characters vanishing only to reappear in another form. Betty’s Aunt Ruth is described as ‘acting in Canada’ which is an industry euphemism for death. Betty discovers Diane’s corpse, yet in many interpretations her death could not have happened yet, not if the first half of the film is a fantasy invented by the living Diane. These kinds of repetitions haunt us because they do not fit but rather they indicate a fissure in the fabric of the narrative which cannot be closed.

There is something uncanny too in the way that Rita lies as still as death on the bed of Betty’s absent (dead?) aunt. She lies like a wound-down doll, waxen and unreal in almost the same position that Diane’s corpse is discovered in. This presentation owes its charge to the horror the viewer feels in recognising something which looks human but may not be. Rita invokes this kind of horror not only because she is so still, but because she repeats the idea of Aunt Ruth’s disappearance and possible death and also because she foreshadows Diane’s corpse. There is the additional strangeness of her memory loss. She could easily be mistaken for something not quite human as she is without identity. When she wakes up in the bed, she speaks Spanish as though channelling the words of someone else. In fact these words are later repeated in the club she and Betty visit by the compėre.

If we place ourselves as viewers, as the desiring eye, as Betty, we can see how her gaze upon Rita’s body could become erotically charged, and also sadistically thrilling. There is the added issue of Betty as a voyeur – she is seen staring at Rita when she is vulnerable – in the shower, asleep, naked. We too watch Rita in these states and can, if we so wish, watch her over and over again, we can subject her to erotic, sadistic repetition. Rita is clearly the site of doubling, she stands in for aunt Rita and the dead Diane.

Though the ugly realities of death are never fully repressed in this film, they are never quite realised or explained either. Yet there is something about this repetition of deaths and disappearances which seems to intensify the desire between the two women. In the first half Rita loses her memory, her identity and eventually her appearance becomes like Betty’s. She becomes gradually eroded, less distinct. This leads her to an emotional and sexual dependence on Betty. Diane loses everything – her career, her lover, her freedom and her sanity. Yet she still desires the dead Camilla, author of her pain. There is no freedom from this desire. It is subject to endless repetition, until both women are dead. – LJ

References

Ahmed, Sara, Queer Phenomenology. Duke University Press: London (2006)

Cicciolina and Explicit Sex Films” pp. 188 – 208 in Aaron, Michelle (ed.), The Body’s Perilous Pleasures: Dangerous Desires and Contemporary Culture Edinburgh University Press: Edinburgh (1999)

Love, Heather K., ‘Spectacular Failure: The Figure of the Lesbian in Mulholland Drive’ in New Literary History: a Journal of Theory and Interpretation (University of Virginia, Charlottesville) (35:1) [Winter 2004] p.117-132

RSS - Posts

RSS - Posts

empowered Thinking

Queer Uncanny#1: Mulholland Drive “Have you done this Before?” – Global Queer Cinema